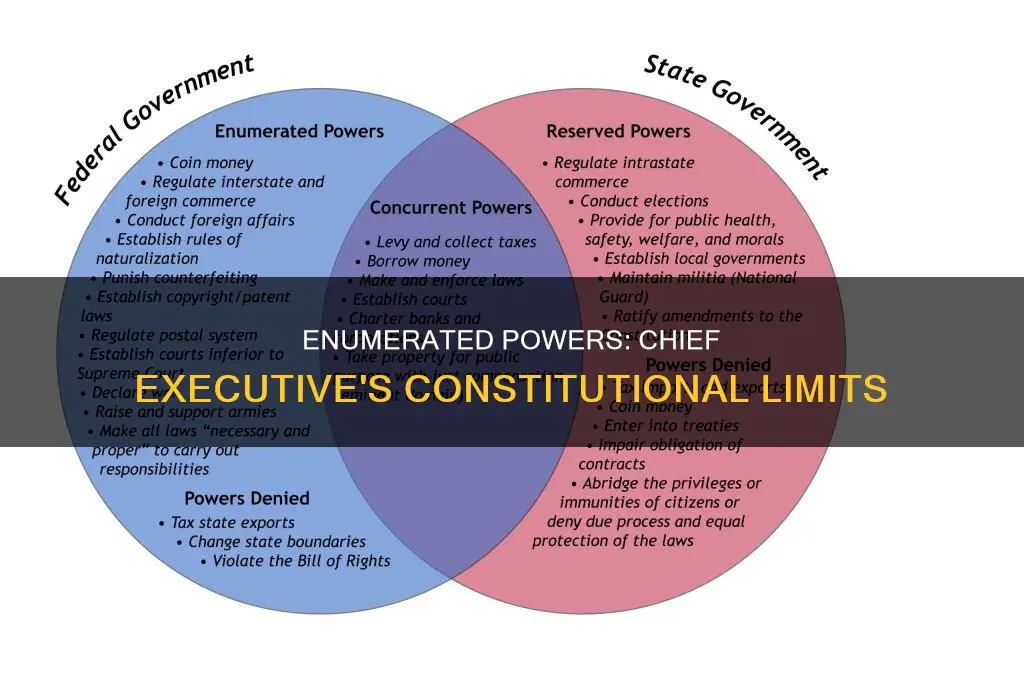

The President of the United States derives their powers from two primary sources: the Constitution and Acts of Congress. Article II of the Constitution enumerates the president's powers and duties, including the power to approve or veto legislation, command the armed forces, ask for the written opinion of their Cabinet, convene or adjourn Congress, grant reprieves and pardons, and receive ambassadors. The president is also the Commander-in-Chief of the United States Armed Forces and has the authority to conduct warfare, deploy troops, and direct military operations. In addition to the powers explicitly granted by the Constitution, the president also has implied powers and soft power attached to the office. The exact scope of these powers has been the subject of much debate, with Congress at times granting the president broad authority and at other times attempting to restrict it.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States | Can conduct warfare, deploy troops, and instruct generals to undertake military operations in defense of national security |

| Power to grant reprieves and pardons | Can grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment |

| Power to make treaties | Can make treaties, which need to be ratified by two-thirds of the Senate |

| Power to appoint officers | Can appoint Article III judges and other officers with the advice and consent of the Senate |

| Power to fill vacancies | Can fill up all vacancies that may happen during the recess of the Senate, by granting commissions which expire at the end of their next session |

| Power to issue directives and executive orders | Can issue directives and executive orders, which can be modified or revoked by the president |

| Power to control and operate federal government, federal agencies, and foreign affairs | Can control and operate the federal government, federal agencies, and foreign affairs |

| Power to approve or veto bills and resolutions passed by Congress | Can approve or veto bills and resolutions passed by Congress |

| Power to convene or adjourn Congress | Can convene or adjourn Congress |

| Power to nominate ambassadors | Can nominate ambassadors and other officials with the advice and consent of Congress |

| Power to execute laws faithfully | Can execute laws faithfully, subject to congressional authorization |

| Power to receive written opinions from principal officers of executive departments | Can receive written opinions from principal officers of executive departments on any subject relating to the duties of their offices |

| Power to protect and defend the Constitution | Shall preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States |

| Eligibility requirements | Must be a natural-born citizen, at least 35 years old, and have been a resident of the United States for at least 14 years |

Explore related products

$18.55 $27.95

$29.95 $29.95

$26.35 $26.95

What You'll Learn

Commander-in-Chief of the US Armed Forces

The President of the United States is the Commander-in-Chief of the US Armed Forces. This power is established in Article II of the Constitution, which names the president as the "Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States."

As Commander-in-Chief, the president has supreme operational command and control over the US Armed Forces, including the power to launch, direct and supervise military operations, order or authorise the deployment of troops, and unilaterally launch nuclear weapons. The president can also form military policy with the Department of Defense and Homeland Security. The military chain of command flows from the President to the Secretary of Defense (for services under the Defense Department) or the Secretary of Homeland Security (for services under the Department of Homeland Security).

The exact degree of authority that the Constitution grants to the president as commander-in-chief has been debated throughout American history. While Congress has, at times, granted the president wide authority, it has also attempted to restrict that authority. There is a consensus that the framers of the Constitution intended Congress to declare war, while the president would direct the war. This interpretation is supported by Alexander Hamilton, who stated that the president, although lacking the power to declare war, would have "the direction of war when authorized or begun".

In times of war or national emergency, Congress may grant the president broader powers to manage the national economy and protect the security of the United States. These powers, however, are not expressly granted by the Constitution. The president's primary sources of power are the Constitution and powers granted by Congress.

Border Fence: Constitutional or Unconstitutional?

You may want to see also

Power to approve or veto legislation

The President of the United States has the power to approve or veto legislation. This power is derived from Article II of the United States Constitution, which outlines the executive powers of the president. The president's role in the legislative process is crucial, as they have the authority to sign or veto bills passed by Congress. This power allows the president to approve and enact legislation that aligns with their policies and agenda.

When a bill is passed by both houses of Congress, it is presented to the president for approval. The president has several options when considering a bill. They may choose to approve the bill and sign it into law, or they may exercise their veto power and reject it. The veto power is a significant check on the legislative branch, as it allows the president to prevent a bill from becoming law. However, it is important to note that Congress can override a presidential veto by passing the bill again with a two-thirds majority vote in both the Senate and the House of Representatives. This process underscores the system of checks and balances between the executive and legislative branches of the US government.

The president's power to approve or veto legislation also extends to executive orders. Executive orders are directives issued by the president that have the force of law. While they are typically used to manage national affairs, federal agencies, and foreign relations, they cannot directly override federal law. If an executive order conflicts with a federal law, it can be deemed invalid by the courts. Additionally, Congress can override an executive order by passing a new law or withholding funding for programs created by the order.

In certain situations, the president's power to approve or veto legislation may be expanded or restricted. For example, during times of war or national emergency, Congress may grant the president broader powers to manage the national economy and protect the security of the nation. On the other hand, Congress may also pass laws or use funding restrictions to limit the president's executive powers. The dynamic between the president and Congress in shaping legislation is a complex and evolving aspect of the US political system.

It is worth noting that the president's legislative power is not limited to approval or veto. They also have the power to propose and introduce legislation, although this is often done through members of Congress. The president can use their influence and agenda to shape the legislative process from the beginning, working with members of Congress to draft and introduce bills that align with their priorities. This aspect of legislative power is often a key component of a president's policy agenda and can significantly impact the direction of the country.

Dividing Powers: The Constitutional Trinity

You may want to see also

Ability to issue executive orders

The president of the United States has the power to issue executive orders, which are written directives that order the government to take specific actions to ensure "the laws be faithfully executed". While the Constitution does not explicitly permit the use of executive orders, Article II, Section 1, Clause 1 of the Constitution vests executive powers in the president, requiring that the president "shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed".

The president's power to issue executive orders stems from two primary sources: the Constitution and powers granted to the president by Congress. This was affirmed in the Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952) Supreme Court decision by Justice Hugo Black, who stated:

> "The President’s power, if any, to issue the order must stem either from an act of Congress or from the Constitution itself."

Executive orders can have the same effect as federal laws under certain circumstances, but they cannot override federal laws and statutes. They are subject to judicial review and may be overturned if they lack support by statute or the Constitution. While the president can modify or revoke executive orders issued during their term, they cannot use an executive order to take over powers from other branches, such as the power vested in Congress to pass new statutes.

Executive orders have been used to create federal institutions, such as the Export-Import Bank of the United States and the National Labor Relations Board. They have also been used to block the entry of certain foreign nationals into the United States, as seen in Trump v. Hawaii (2018). In times of war or national emergency, Congress may grant the president broader powers to issue executive orders to manage the national economy and protect the security of the United States.

The Constitution: Ensuring Popular Sovereignty

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$28.49 $29.99

$9.99 $9.99

Control of foreign affairs

The US Constitution contains ambiguities regarding the roles of Congress and the President in making foreign policy. The President's foreign affairs powers are enshrined in Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution, which states that "the executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America."

Article II also gives the President the ability to negotiate treaties, with the advice and consent of the Senate, and to appoint ambassadors and other "public Ministers and consuls," which grants the President several foreign affairs powers. The President, as Commander in Chief, has the responsibility to superintend the military, and Congress and the President have interlinked authorities with respect to the military.

The Supreme Court has held that the Executive retains exclusive authority over the recognition of foreign sovereigns and their territorial bounds. The Court has also concluded that the Constitution confers recognition power to the President, and that this power is not shared with Congress.

Congress's greatest authority over US foreign policy is its "power of the purse." Since Congress has the sole power to appropriate monies, it can determine how money can be used, which can be expressed as a policy applicable to the use of funds or as a restriction on their use. Congress also has the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, to declare war, and to approve treaties and ambassadors.

In practice, there have been several conflicts between the President and Congress over foreign policy powers, such as the debate over the use of US troops to liberate Kuwait following Iraq's invasion in 1990, and President George W. Bush's 2003 invasion of Iraq.

The US Constitution: A Comprehensive Article Count

You may want to see also

Authority to appoint and remove executive officers

The President of the United States is granted several powers by the Constitution, including the authority to appoint and remove executive officers. This power is derived from Article II of the Constitution, which grants the President "the executive power of the Government," or the "general administrative control of those executing the laws." This includes the power of appointment and removal of executive officers, as confirmed by the President's obligation to ensure the faithful execution of the laws.

The Appointments Clause of the Constitution vests the President with the authority to appoint officers, including federal judges, ambassadors, and Cabinet-level department heads, with the "Advice and Consent of the Senate." The President may also make temporary appointments during a Senate recess, filling vacancies until the end of the next Senate session.

The President's authority to remove executive officers has been the subject of several Supreme Court cases and debates over the separation of powers. While the Constitution does not explicitly address the removal of federal appointees, the Court has affirmed that the power to remove appointed officials, except federal judges, rests solely with the President without requiring congressional approval. Congress may, however, limit the President's removal power in certain cases, especially regarding independent agencies and inferior officers.

The President's power to appoint and remove executive officers allows them to direct officials on staffing, personnel decisions, and legal interpretations, subject to judicial review. This authority contributes to the President's ability to manage national affairs and the priorities of the government.

In conclusion, the President's authority to appoint and remove executive officers is a significant power granted by the Constitution. It enables the President to shape their administration, ensure the execution of laws, and direct the country's policies and operations. While Congress can limit this power in specific cases, the President ultimately holds the removal power for most executive officers, influencing the composition of the federal government.

The Constitution: A Long and Winding Debate

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Article II of the Constitution enumerates several powers granted to the Chief Executive, or President of the United States. While there is no exact number, the Constitution grants the President broad powers in several areas, including foreign affairs, federal agencies, and the control and operation of the federal government.

The President has the power to approve or veto bills and resolutions passed by Congress, propose treaties with other countries, and direct the nation's diplomatic corps. The President is also the Commander-in-Chief of the US Armed Forces and has the power to deploy troops and conduct warfare.

In addition to the powers enumerated in Article II, the President has implied powers that are not expressly granted by the Constitution but are derived from the broad scope of the express powers. For example, in certain cases, the Supreme Court has ruled that the President has the inherent authority to act within their "implied powers."

Yes, Congress can grant additional powers to the President by statute and can also restrict the President's powers. For example, Congress can override a presidential veto with a two-thirds vote and can withhold spending on programs created by an executive order. In times of war or national emergency, Congress may grant the President broader powers, such as managing the national economy and protecting national security.