Political utilitarianism, a philosophy rooted in maximizing overall happiness or utility, often faces criticism for its potential to justify morally questionable actions in the pursuit of greater good. Critics argue that this approach can lead to the marginalization of minority groups, as their interests may be sacrificed if they do not align with the majority's well-being. Additionally, utilitarianism's focus on quantifiable outcomes can overlook qualitative aspects of justice, fairness, and individual rights, potentially enabling authoritarian or oppressive regimes to rationalize their actions under the guise of utility. Furthermore, the difficulty of accurately measuring and predicting collective happiness raises concerns about its practical application, as decisions based on flawed or biased calculations could exacerbate inequality and harm vulnerable populations. These limitations highlight the ethical and practical challenges inherent in applying utilitarian principles to political decision-making.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Ignores Individual Rights | Prioritizes collective happiness over individual freedoms and rights. |

| Justifies Oppression of Minorities | Can justify policies that harm minorities if it benefits the majority. |

| Difficult to Measure Utility | Lacks a clear, objective method to quantify happiness or utility. |

| Short-Term Focus | May prioritize immediate gains over long-term consequences. |

| Moral Compromises | Can justify morally questionable actions if they maximize overall utility. |

| Ignores Distributive Justice | Fails to address inequality, as long as total utility is maximized. |

| Overemphasis on Consequences | Ignores the intentions or moral principles behind actions. |

| Potential for Tyranny of the Majority | Risks marginalizing minority groups in favor of majority preferences. |

| Subjectivity in Defining Happiness | Different individuals or groups may define happiness differently. |

| Neglects Intrinsic Values | Focuses solely on outcomes, disregarding intrinsic moral or ethical values. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Ignores individual rights for majority benefit

Political utilitarianism, with its focus on maximizing overall happiness or utility, often justifies sacrificing individual rights for the perceived greater good. This approach raises a critical ethical dilemma: at what point does the pursuit of collective benefit become a threat to personal freedoms? Consider a scenario where a government, guided by utilitarian principles, enacts policies that infringe on minority rights to achieve majority satisfaction. For instance, a law might restrict freedom of speech to prevent dissent that could disrupt social harmony. While this may increase overall stability, it undermines the fundamental rights of those whose voices are silenced. The danger lies in the slippery slope: once individual rights are deemed expendable for the majority, the criteria for who is sacrificed and why become increasingly arbitrary.

To illustrate, imagine a healthcare policy that rations medical resources based on utilitarian calculations. A 70-year-old with a chronic condition might be denied treatment because the resources could save more lives if allocated to younger, healthier individuals. Here, the individual’s right to healthcare is overridden for the greater statistical benefit. This raises a moral question: is it justifiable to assign value to one life over another based on age, productivity, or societal contribution? Utilitarianism, in this context, risks dehumanizing individuals by reducing their worth to a numerical contribution to the collective utility.

From a practical standpoint, ignoring individual rights for majority benefit can lead to systemic oppression and erode trust in institutions. History provides cautionary tales, such as the forced relocation of indigenous communities for economic development projects. While these actions may have boosted GDP or resource extraction, they inflicted irreparable harm on marginalized groups. The takeaway is clear: utilitarian policies must be scrutinized for their potential to disproportionately burden vulnerable populations. A balanced approach requires embedding safeguards, such as minority rights protections, into decision-making frameworks to prevent the tyranny of the majority.

Persuasively, one must argue that individual rights are not mere obstacles to collective progress but the bedrock of a just society. Utilitarianism’s focus on outcomes overlooks the intrinsic value of personal autonomy and dignity. For example, a policy that mandates universal surveillance to reduce crime rates may achieve its goal but at the cost of privacy and freedom. The question then becomes: is a society truly better off if its citizens live in constant fear of scrutiny? By prioritizing majority benefit without regard for individual rights, utilitarianism risks creating a society where conformity is enforced, and dissent is punished, ultimately stifling innovation and diversity.

In conclusion, while political utilitarianism aims for the greatest good, its tendency to ignore individual rights for majority benefit poses significant ethical and practical challenges. From healthcare rationing to oppressive policies, the consequences of sacrificing personal freedoms are far-reaching. To mitigate these risks, policymakers must adopt a nuanced approach that balances collective welfare with the protection of individual rights. Only then can utilitarian principles be applied in a manner that is both just and sustainable.

Prosecutors and Politics: Unraveling Their Role in the Political Landscape

You may want to see also

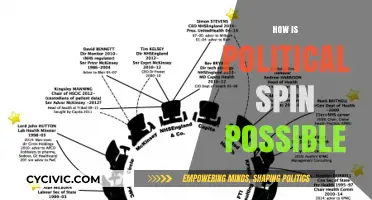

Justifies harmful policies if deemed greater good

Political utilitarianism, with its core principle of maximizing overall happiness, often leads to a dangerous justification of harmful policies under the guise of the "greater good." This approach assumes that the ends always justify the means, a premise that can erode ethical boundaries and individual rights. For instance, a government might implement mass surveillance, arguing that it prevents crime and ensures societal safety, even if it infringes on privacy and freedom. While the intent may seem noble, the long-term consequences of such policies can include normalized authoritarianism and a loss of trust in institutions. This slippery slope illustrates how utilitarianism, when applied rigidly, prioritizes collective benefit over the protection of fundamental human rights.

Consider the historical example of forced sterilization programs in the early 20th century, justified under eugenic principles to "improve" the genetic quality of the population. These policies, rooted in utilitarian logic, caused irreversible harm to marginalized groups, particularly women and people of color. The calculation of greater good here ignored the inherent dignity and autonomy of individuals, treating them as expendable for a perceived societal benefit. Such cases highlight the moral hazard of utilitarianism: when the focus shifts to aggregate outcomes, the suffering of minorities or vulnerable populations becomes an acceptable cost, undermining the very concept of justice.

To avoid these pitfalls, policymakers must adopt a framework that balances utilitarian goals with deontological principles, ensuring that certain actions remain unacceptable regardless of their outcomes. For example, instead of justifying invasive public health measures like mandatory vaccinations solely on the basis of herd immunity, governments should prioritize informed consent and equitable access to healthcare. This dual approach acknowledges the importance of collective well-being while safeguarding individual rights. Practical steps include conducting rigorous ethical reviews of policies, engaging with affected communities, and establishing clear limits on state intervention.

A comparative analysis of utilitarianism and other ethical theories reveals its limitations. While utilitarianism excels in addressing large-scale issues like resource allocation, it falters when confronted with dilemmas requiring moral absolutes. For instance, a utilitarian might argue for redistributing wealth to reduce inequality, even if it involves coercive taxation. In contrast, a rights-based approach would emphasize voluntary participation and fair processes. By integrating these perspectives, policymakers can design interventions that are both effective and just, avoiding the trap of sacrificing individual welfare for abstract notions of the greater good.

Ultimately, the allure of utilitarianism lies in its simplicity: quantify happiness, and act accordingly. However, this reductionist approach overlooks the complexity of human values and the irreplaceable nature of certain rights. To mitigate its risks, societies must foster a culture of critical inquiry, questioning policies that claim to serve the greater good at the expense of specific groups. By doing so, we can harness the strengths of utilitarianism while guarding against its potential to justify harm, ensuring that the pursuit of collective happiness never comes at the cost of humanity’s moral integrity.

How Political Power Shapes Media Narratives and Public Perception

You may want to see also

Struggles with minority protections and fairness

Political utilitarianism, with its focus on maximizing overall happiness or utility, often struggles to protect minority rights and ensure fairness. This is because the majority’s preferences can overshadow the needs of smaller, marginalized groups, leading to systemic injustices. For instance, policies that benefit the majority might disproportionately harm minorities, such as indigenous communities losing land rights to large-scale development projects. The utilitarian calculus, while mathematically appealing, fails to account for the qualitative differences in how harm is experienced by vulnerable populations.

Consider the practical implications of this imbalance. In healthcare allocation, a utilitarian approach might prioritize funding treatments that benefit the largest number of people, even if it means neglecting rare diseases affecting small groups. This creates a moral dilemma: is it just to sacrifice the well-being of a few for the greater good? Critics argue that such decisions erode the principle of equality, as minority groups are repeatedly forced to bear the brunt of collective utility. To mitigate this, policymakers could adopt a "minority impact assessment" framework, requiring that any policy’s effects on marginalized groups be explicitly evaluated before implementation.

Another challenge arises in the realm of political representation. Utilitarian systems often favor majority rule, which can marginalize minority voices in decision-making processes. For example, in electoral systems, smaller political parties or ethnic groups may struggle to gain traction, leading to their interests being systematically ignored. This lack of representation perpetuates inequality and undermines the fairness of the political system. A potential solution lies in proportional representation models, which ensure that minority groups have a guaranteed seat at the table, balancing utilitarian efficiency with equitable participation.

Finally, the utilitarian emphasis on aggregate outcomes can obscure individual injustices. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, some governments justified strict lockdowns by citing the greater good, despite the disproportionate economic and psychological toll on low-income communities and essential workers. This highlights the need for a nuanced approach that pairs utilitarian principles with robust protections for individual and minority rights. Incorporating a "fairness threshold" into policy design—a minimum standard of protection for vulnerable groups—could help reconcile utilitarian goals with ethical governance. Without such safeguards, political utilitarianism risks becoming a tool for oppression rather than a framework for justice.

Is Bruce Springsteen Political? Exploring the Boss's Social Commentary

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Encourages short-term gains over long-term stability

Political utilitarianism, with its focus on maximizing overall happiness, often prioritizes immediate benefits at the expense of long-term stability. This tendency is particularly evident in policy-making, where leaders may opt for quick fixes that yield visible results during their tenure, even if those solutions undermine future resilience. For instance, a government might slash corporate taxes to stimulate short-term economic growth, ignoring the long-term consequences of reduced public funding for education, healthcare, and infrastructure. Such decisions create a cycle of dependency on temporary measures, leaving societies vulnerable to systemic failures down the line.

Consider the environmental policies of nations that prioritize industrial growth over sustainability. A utilitarian approach might justify increased pollution or deforestation if it boosts GDP and employment in the near term. However, this neglects the irreversible damage to ecosystems, which will inevitably lead to resource scarcity, climate crises, and economic instability for future generations. The short-sightedness of such policies highlights a critical flaw in utilitarianism: its inability to account for the cumulative impact of decisions over time.

To mitigate this issue, policymakers must adopt a dual-lens approach, balancing immediate utility with long-term sustainability. For example, instead of solely focusing on job creation through fossil fuel industries, governments could invest in renewable energy sectors, which offer both short-term employment and long-term environmental benefits. This requires a shift in mindset, from maximizing happiness now to ensuring its continuity for decades to come. Practical steps include implementing stricter regulations on industries, incentivizing sustainable practices, and fostering public awareness about the trade-offs between short-term gains and long-term stability.

A cautionary tale lies in the 2008 financial crisis, where deregulation and risky lending practices provided short-term economic benefits but ultimately led to global economic collapse. This example underscores the danger of utilitarianism’s myopia, where the pursuit of immediate happiness ignores systemic risks. To avoid repeating such mistakes, leaders must prioritize policies that build resilience, even if they yield less immediate gratification. By doing so, they can ensure that the pursuit of happiness does not come at the cost of future stability.

Polling Power: Shaping Political Strategies and Public Opinion Dynamics

You may want to see also

Risks moral relativism and ethical ambiguity

Political utilitarianism, with its focus on maximizing overall happiness or utility, often blurs the lines between absolute moral principles and situational ethics. This approach risks sliding into moral relativism, where actions are judged solely by their outcomes rather than their inherent rightness or wrongness. For instance, a utilitarian government might justify surveillance programs as necessary for public safety, even if they infringe on individual privacy rights. The danger lies in the erosion of fixed ethical standards, leaving society vulnerable to justifications for actions that, under a more rigid moral framework, would be deemed unacceptable.

Consider the example of resource allocation in healthcare. A utilitarian approach might prioritize funding treatments that benefit the largest number of people, potentially neglecting rare diseases affecting smaller populations. While this maximizes overall utility, it raises ethical questions about fairness and the intrinsic value of individual lives. Such decisions, though mathematically efficient, can foster a moral ambiguity where the ends consistently justify the means, regardless of the ethical compromises involved.

To mitigate these risks, policymakers must balance utilitarian calculations with deontological principles—rules-based ethics that emphasize duties and rights. For example, establishing clear thresholds for acceptable trade-offs between collective benefits and individual rights can provide a safeguard against moral relativism. In practice, this could mean legislating that certain rights, such as freedom of speech or privacy, are non-negotiable, even if their restriction might yield greater overall utility in specific scenarios.

Another practical step is fostering public dialogue to scrutinize utilitarian policies. Engaging diverse perspectives ensures that ethical ambiguities are not overlooked in the pursuit of efficiency. For instance, community forums or advisory boards can serve as checks on government decisions, highlighting potential moral pitfalls that quantitative analyses might miss. This participatory approach not only strengthens democratic processes but also reinforces a shared commitment to ethical clarity.

Ultimately, the allure of utilitarianism lies in its promise of objective, data-driven decision-making. However, its implementation demands vigilance against the creeping dangers of moral relativism and ethical ambiguity. By anchoring utilitarian principles within a broader ethical framework and encouraging transparent, inclusive decision-making, societies can harness its benefits while preserving moral integrity. The challenge is not to abandon utilitarianism but to refine it, ensuring that the pursuit of the greatest good does not come at the expense of ethical certainty.

Is Nicaraguan Politics Still Republican? Analyzing the Current Political Landscape

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political utilitarianism is the application of utilitarian principles (maximizing overall happiness or well-being) to political decision-making. It is criticized for potentially justifying actions that harm minorities or individuals in the pursuit of greater collective benefit, leading to ethical dilemmas and injustices.

Political utilitarianism prioritizes the greater good over individual rights, meaning that the rights of a few may be sacrificed if it benefits the majority. This can lead to the oppression of minorities or vulnerable groups, as their interests are deemed less important than the collective whole.

Yes, because utilitarianism focuses on outcomes rather than the means to achieve them, it can justify oppressive policies if they are believed to produce the greatest good. This opens the door to authoritarian regimes that prioritize efficiency and control over freedom and justice.

Political utilitarianism relies on accurately measuring and comparing the well-being of individuals, which is often impossible due to subjective definitions of happiness and the complexity of societal needs. This impracticality can lead to arbitrary or biased decision-making.

Utilitarianism focuses on aggregate outcomes rather than the distribution of benefits and burdens. This can result in systemic inequalities, as the well-being of the majority may be achieved at the expense of marginalized groups, ignoring principles of fairness and justice.