The Era of Good Feelings, spanning from 1815 to 1825, was a period in American history marked by a sense of national unity and political harmony, largely dominated by the Democratic-Republican Party. Following the War of 1812, the Federalist Party declined significantly, leaving the Democratic-Republicans as the sole major political force. This era, often associated with President James Monroe's administration, saw the party's influence shape policies and governance without significant opposition. The absence of partisan conflict fostered a perception of national cohesion, though underlying regional and ideological tensions persisted. The Democratic-Republicans' dominance during this time exemplified how a single political party could define an era, even as the seeds of future divisions were quietly being sown.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Single-Party Dominance | The Democratic-Republican Party was the sole major political party. |

| Reduced Partisan Conflict | Minimal opposition led to a sense of unity and reduced political rivalry. |

| National Unity | Emphasis on shared American identity over partisan divisions. |

| Economic Prosperity | Post-War of 1812 economic growth and expansion. |

| Sectional Harmony | Temporary easing of tensions between Northern and Southern states. |

| Strong Executive Leadership | President James Monroe’s leadership fostered stability. |

| Limited Political Opposition | Federalist Party declined, leaving no significant opposition. |

| Era of Consensus | Agreement on key issues like nationalism and economic policies. |

| Expansionist Policies | Support for westward expansion and the Monroe Doctrine. |

| Cultural Optimism | A sense of national pride and optimism about America’s future. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Economic Prosperity: National bank, tariffs, and internal improvements fostered economic growth and unity

- Political Dominance: Democratic-Republicans controlled government, reducing partisan conflict

- Sectional Harmony: Regional differences were temporarily overshadowed by national interests

- Monroe Doctrine: Asserted U.S. dominance in the Americas, boosting national pride

- Era's Limitations: Excluded Native Americans, slavery issues, and one-party rule concerns

Economic Prosperity: National bank, tariffs, and internal improvements fostered economic growth and unity

The Era of Good Feelings, a period marked by single-party dominance under President James Monroe, saw significant economic prosperity driven by strategic policies. At the heart of this growth was the establishment of the Second Bank of the United States, which stabilized the nation’s currency and credit systems. By regulating state banks and providing a uniform currency, the national bank facilitated interstate commerce and reduced financial chaos. This institution became a cornerstone of economic unity, ensuring that businesses and farmers across the country operated within a predictable financial framework. Without such a centralized system, regional economies might have diverged, weakening the nation’s overall economic resilience.

Tariffs played a dual role in fostering economic growth during this era. Protective tariffs, like the Tariff of 1816, shielded American industries from foreign competition, particularly from Britain, allowing domestic manufacturers to flourish. These tariffs also generated substantial revenue for the federal government, which was reinvested in internal improvements. Critics argue that tariffs disproportionately benefited the North, but they undeniably spurred industrialization and created jobs. For instance, textile mills in New England expanded rapidly, transforming the region into an economic powerhouse. Tariffs, therefore, were not just economic tools but also instruments of national cohesion, tying the interests of diverse regions to a shared industrial destiny.

Internal improvements, such as roads, canals, and bridges, were the physical manifestation of economic unity. The National Road, stretching from Maryland to Illinois, and the Erie Canal, connecting the Great Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean, revolutionized transportation and trade. These projects reduced the cost of moving goods, opened new markets, and fostered economic interdependence among states. However, the federal role in funding these improvements was contentious, with strict constructionists arguing it exceeded constitutional authority. Despite this, the economic benefits were undeniable: regions once isolated became integrated into a national economy, and the mobility of goods and people accelerated growth.

To replicate such economic unity today, policymakers could draw lessons from this era. First, invest in modern infrastructure—think high-speed rail, broadband, and renewable energy grids—to connect regions and stimulate innovation. Second, balance trade policies to protect nascent industries while avoiding isolationism. Finally, establish financial institutions that prioritize stability and inclusivity, ensuring all regions benefit from economic growth. The Era of Good Feelings demonstrates that economic prosperity is not just about growth but about creating systems that bind a nation together. By focusing on these three pillars—banking, tariffs, and infrastructure—leaders can foster unity through shared economic success.

Switching Political Parties in East Baton Rouge Parish: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

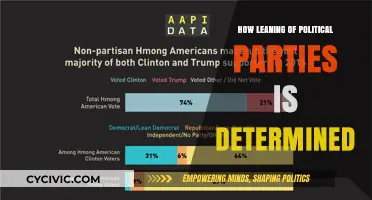

Political Dominance: Democratic-Republicans controlled government, reducing partisan conflict

The early 19th century in the United States, often referred to as the Era of Good Feelings, was marked by an unprecedented level of political unity, primarily due to the dominance of the Democratic-Republican Party. This period, spanning from 1815 to 1825, saw the party control both the presidency and Congress, effectively minimizing partisan conflict and fostering a sense of national cohesion. James Monroe’s presidency, in particular, exemplified this dominance, as he ran virtually unopposed in the 1820 election, symbolizing the era’s political unanimity. This single-party control allowed for a focused agenda, prioritizing national expansion, infrastructure development, and economic growth, rather than ideological battles.

Analyzing the mechanisms of this dominance reveals a strategic alignment of interests. The Democratic-Republicans capitalized on post-War of 1812 nationalism, framing their policies as essential to American prosperity and unity. By championing initiatives like the Missouri Compromise and the construction of roads and canals, they appealed to both Northern and Southern interests, reducing regional tensions. This pragmatic approach not only solidified their hold on power but also marginalized the Federalist Party, which struggled to regain relevance after opposing the war. The result was a political landscape where dissent was minimal, and governance became more about execution than debate.

However, this dominance was not without its drawbacks. The absence of a strong opposition party led to complacency and a lack of accountability. For instance, the Panic of 1819 exposed economic vulnerabilities, yet the Democratic-Republicans faced little pressure to address systemic issues. This period of unity, while productive in many ways, also highlighted the dangers of unchecked power. It serves as a cautionary tale: while political dominance can streamline governance, it risks stifling dissent and overlooking critical problems.

To replicate the positive aspects of this era in modern contexts, leaders should focus on fostering consensus through inclusive policies that address diverse interests. For example, infrastructure projects that benefit both urban and rural areas can bridge divides. However, mechanisms for accountability must be maintained, such as robust media scrutiny and active civic engagement. The Era of Good Feelings demonstrates that unity is achievable but requires balancing dominance with transparency and responsiveness to avoid the pitfalls of one-party rule.

In practical terms, organizations or governments seeking to emulate this model should prioritize cross-sector collaboration, regularly assess public sentiment, and encourage constructive criticism. For instance, holding town hall meetings or creating advisory councils can ensure diverse voices are heard. While the Democratic-Republicans’ dominance reduced partisan conflict, modern adaptations must actively prevent the concentration of power by institutionalizing checks and balances. This approach ensures that unity does not come at the expense of democratic vitality.

Changing Political Party Affiliation in New Jersey: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Sectional Harmony: Regional differences were temporarily overshadowed by national interests

The early 1800s in the United States, often referred to as the Era of Good Feelings, witnessed a remarkable phenomenon: the temporary eclipse of regional differences by a unifying national sentiment. This period, dominated by the Democratic-Republican Party, saw Americans rallying around shared goals rather than divisive local interests. The War of 1812, for instance, fostered a sense of national pride and unity, as citizens from the North, South, and West celebrated victories like the Battle of New Orleans. This collective triumph temporarily muted the economic and cultural disparities that would later fuel sectional conflict.

Consider the economic policies of the time, which illustrate this sectional harmony. The Second Bank of the United States, established in 1816, aimed to stabilize the national economy, benefiting both agrarian Southerners and industrializing Northerners. Similarly, the American System, championed by Henry Clay, proposed internal improvements like roads and canals, projects that promised to connect regions rather than isolate them. These initiatives reflected a consensus that national prosperity was intertwined with regional development, at least for a time.

However, this harmony was fragile and contingent on external factors. The absence of a second political party during this era reduced partisan conflict, allowing national interests to take precedence. Yet, this unity was not rooted in the resolution of underlying tensions but rather in their temporary suppression. For example, the Missouri Compromise of 1820, while averting immediate crisis over slavery, merely postponed the inevitable clash between free and slave states. Such compromises highlight the era’s ability to paper over differences rather than genuinely reconcile them.

To understand this dynamic, imagine a household where family members agree to set aside their disagreements during a holiday gathering. The celebration fosters unity, but the underlying issues remain unresolved. Similarly, the Era of Good Feelings was a period of national celebration and consensus, but it lacked the mechanisms to address the deep-seated regional divisions that would later resurface. This analogy underscores the era’s transient nature and the importance of recognizing its limitations.

In practical terms, this period offers a lesson in the power of shared purpose. For modern policymakers, fostering national unity requires identifying common goals that transcend regional interests. However, it also serves as a cautionary tale: temporary harmony is not sustainable without addressing the root causes of division. By studying this era, we can learn how to build consensus while remaining vigilant about the underlying tensions that threaten long-term stability.

Why Jachai Polite Was Cut: Analyzing the Sudden NFL Departure

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Monroe Doctrine: Asserted U.S. dominance in the Americas, boosting national pride

The Monroe Doctrine, articulated in 1823, stands as a pivotal moment in U.S. foreign policy, encapsulating the nation’s growing assertiveness during the Era of Good Feelings. President James Monroe’s declaration warned European powers against further colonization in the Americas, effectively staking a claim to U.S. dominance in the Western Hemisphere. This bold statement was not merely a diplomatic maneuver but a reflection of the nation’s burgeoning sense of identity and power. By positioning the U.S. as the protector of the Americas, the doctrine fostered a surge in national pride, aligning with the era’s unifying political sentiment under the one-party dominance of the Democratic-Republicans.

To understand its impact, consider the historical context. Post-War of 1812, the U.S. sought to solidify its independence and influence. The Monroe Doctrine achieved this by drawing a line in the sand, asserting that the Americas were no longer open to European interference. This was not just a defensive stance but a proactive assertion of U.S. authority. For instance, while the doctrine lacked immediate enforcement mechanisms, it laid the groundwork for future interventions, such as the Roosevelt Corollary, which explicitly tied U.S. military action to its economic interests in Latin America. This evolution underscores the doctrine’s role as a foundational document for U.S. hegemony in the region.

From a practical standpoint, the Monroe Doctrine served as a rallying cry for national unity. During the Era of Good Feelings, the absence of partisan conflict allowed Americans to coalesce around shared ideals of expansion and independence. The doctrine’s emphasis on protecting the Americas from European encroachment resonated deeply with a public eager to assert its place on the global stage. Schools, newspapers, and public speeches celebrated the doctrine as a testament to American strength and virtue, embedding it into the national consciousness. This cultural embrace transformed the policy from a mere diplomatic statement into a symbol of collective ambition.

Critically, however, the doctrine’s legacy is not without controversy. While it bolstered U.S. pride, it also set the stage for imperialist policies that often marginalized Latin American nations. The doctrine’s interpretation as a license for intervention highlights the tension between national pride and ethical foreign policy. For modern readers, this serves as a cautionary tale: assertions of dominance, while unifying, can have unintended consequences. Balancing pride with responsibility remains a challenge, but understanding the Monroe Doctrine’s dual role—as both a unifier and a precursor to imperialism—offers valuable insights into the complexities of national identity and power.

Crafting a Powerful Identity: How to Name Your Political Party

You may want to see also

Era's Limitations: Excluded Native Americans, slavery issues, and one-party rule concerns

The Era of Good Feelings, often associated with the dominance of the Democratic-Republican Party under President James Monroe, is frequently portrayed as a period of national unity and political harmony. However, this rosy narrative obscures significant limitations that reveal the era’s exclusionary nature. Native Americans, for instance, were systematically marginalized through policies like the Indian Removal Act, which laid the groundwork for their displacement. While the federal government negotiated treaties, these agreements often favored expansionist interests, leaving Indigenous communities with little agency or protection. This stark contrast between unity for some and dispossession for others underscores the era’s flawed inclusivity.

Slavery, another critical issue, remained a festering wound beneath the surface of national concord. The Missouri Compromise of 1820, though hailed as a solution to sectional tensions, merely delayed confrontation by admitting Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state. This compromise perpetuated the institution of slavery while failing to address its moral and economic implications. The Era of Good Feelings thus masked deep divisions over human bondage, setting the stage for future conflicts. Its unity was built on the fragile foundation of ignoring the plight of enslaved Africans and their descendants.

One-party rule, often celebrated as a source of stability, carried its own dangers. The absence of meaningful political opposition stifled debate and accountability, allowing the Democratic-Republicans to consolidate power without challenge. This monopoly on governance fostered complacency and corruption, as seen in scandals like the Yazoo land fraud. While the era appeared harmonious, the lack of competing ideas and policies limited innovation and responsiveness to diverse needs. Unity, in this context, became a double-edged sword, suppressing dissent and perpetuating systemic inequalities.

To understand the Era of Good Feelings fully, one must recognize these limitations as integral to its character. Exclusion, compromise, and dominance shaped its legacy, revealing that unity often came at the expense of marginalized groups. Practical steps to address these historical oversights include integrating Indigenous and African American perspectives into curricula, revisiting land rights policies, and fostering multi-party systems to ensure robust political discourse. By acknowledging these flaws, we can move beyond idealized narratives and confront the complexities of our past.

Switching Political Parties in South Dakota: A Simple Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The "Era of Good Feelings" refers to a period in American history from 1815 to 1825, marked by a sense of national unity and reduced partisan conflict following the War of 1812.

The Democratic-Republican Party, led by James Monroe, dominated the era due to the decline of the Federalist Party and widespread agreement on key issues like nationalism and westward expansion.

The Federalist Party declined due to its opposition to the War of 1812, which was unpopular, and its association with regional interests, particularly in New England, while the Democratic-Republicans championed national unity.

President Monroe, a Democratic-Republican, fostered unity by touring the country, emphasizing national pride, and promoting policies like the Missouri Compromise, which temporarily eased sectional tensions.

While the era appeared harmonious due to one-party dominance, underlying tensions over slavery, states' rights, and economic policies persisted, eventually resurfacing in the 1820s and 1830s.

![A History of Violence (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71lqpbUFtWL._AC_UY218_.jpg)