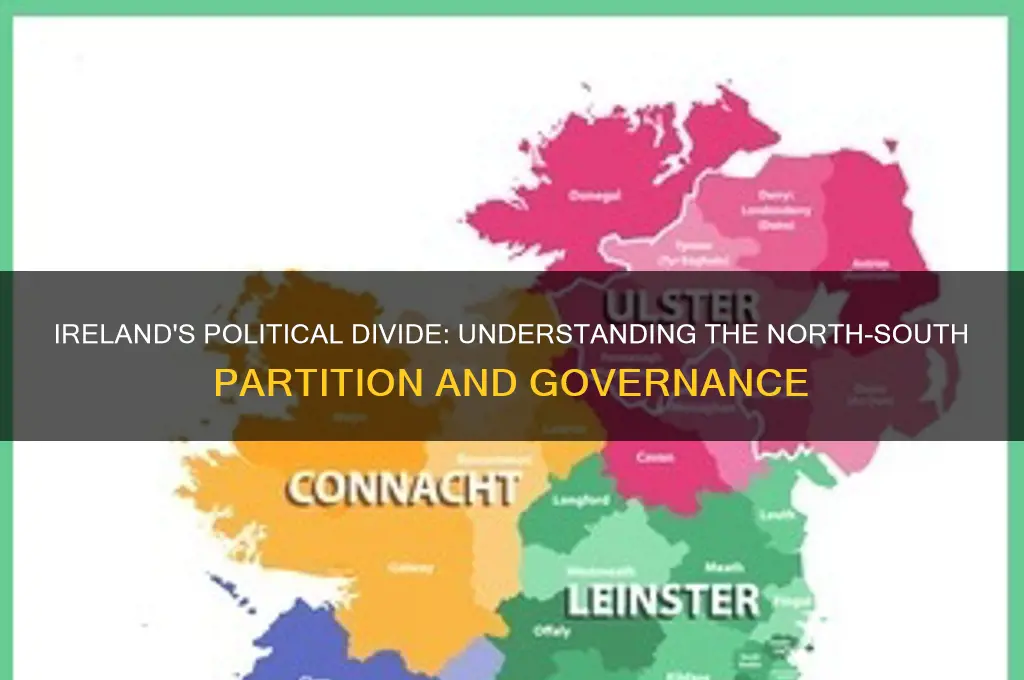

Ireland is politically divided into two distinct entities: the Republic of Ireland, an independent sovereign state occupying approximately five-sixths of the island, and Northern Ireland, which remains a part of the United Kingdom. This division stems from the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921, which partitioned the island, leading to the creation of the Irish Free State (now the Republic of Ireland) and the retention of Northern Ireland within the UK. The partition was deeply rooted in historical, religious, and cultural differences, particularly between the predominantly Catholic nationalist population, who sought independence, and the largely Protestant unionist community, who wished to remain under British rule. This political divide has historically been a source of tension, most notably during the Troubles (1968–1998), a period of conflict in Northern Ireland that resulted in the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, which established a power-sharing government and helped stabilize the region. Today, while the Republic of Ireland operates as a parliamentary republic with its own government and policies, Northern Ireland maintains a devolved administration within the UK framework, reflecting the ongoing complexities of Ireland's political landscape.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Division | Ireland is divided into two separate political entities: the Republic of Ireland (officially Ireland) and Northern Ireland (part of the United Kingdom). |

| Republic of Ireland | - Sovereign state - Capital: Dublin - Government: Parliamentary republic - Head of State: President (currently Michael D. Higgins) - Head of Government: Taoiseach (currently Leo Varadkar) - Legislature: Oireachtas (bicameral parliament with Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann) - Population: ~5.1 million (2023 est.) - Area: ~70,273 km² |

| Northern Ireland | - Part of the United Kingdom - Capital: Belfast - Government: Devolved parliamentary democracy - Head of State: Monarch (King Charles III, represented by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland) - Head of Government: First Minister and deputy First Minister (currently vacant due to political deadlock) - Legislature: Northern Ireland Assembly (unicameral) - Population: ~1.9 million (2023 est.) - Area: ~14,130 km² |

| Border | A 499 km (310 mi) land border separates the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, known as the Irish border. |

| Political Parties | Republic of Ireland: Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael, Sinn Féin, Labour Party, Green Party, etc. Northern Ireland: Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), Sinn Féin, Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), Alliance Party, etc. |

| International Relations | Republic of Ireland: Member of the European Union, United Nations, OECD, WTO, etc. Northern Ireland: As part of the UK, subject to UK foreign policy, but has unique relationships with the Republic of Ireland due to the Good Friday Agreement. |

| Currency | Republic of Ireland: Euro (€) Northern Ireland: Pound sterling (£) |

| Recent Developments | Ongoing discussions around the Northern Ireland Protocol (part of the Brexit withdrawal agreement) and its impact on the Irish border. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Northern Ireland vs. Republic of Ireland: Historical partition, separate governments, distinct political systems

- Nationalist vs. Unionist Views: Competing identities, political loyalties, influence on governance

- Stormont and Dáil Éireann: Regional and national parliaments, legislative differences, powers

- Border and Brexit Impact: Political tensions, trade, cross-border cooperation challenges

- Power-Sharing in Northern Ireland: Consociationalism, coalition governance, stability issues

Northern Ireland vs. Republic of Ireland: Historical partition, separate governments, distinct political systems

Ireland’s political division is rooted in the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty, which partitioned the island into Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State (later the Republic of Ireland). This partition was a response to centuries of colonial rule, religious tensions, and conflicting national identities. Northern Ireland, with its unionist majority favoring ties to Britain, remained part of the United Kingdom, while the predominantly nationalist south sought independence. This historical split created two distinct political entities, each with its own trajectory shaped by geography, culture, and external influences.

The governments of Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland operate under fundamentally different systems. Northern Ireland functions as a devolved region within the UK, with its own assembly and executive based in Stormont, Belfast. Its political landscape is dominated by unionist and nationalist parties, often leading to power-sharing arrangements mandated by the Good Friday Agreement. In contrast, the Republic of Ireland is a sovereign parliamentary republic, governed from Dublin, with a president, Taoiseach (prime minister), and a bicameral legislature. This structural difference reflects their divergent relationships with Britain and their approaches to sovereignty.

The political systems of both regions are also shaped by their histories of conflict and reconciliation. Northern Ireland’s Troubles (1968–1998) left a legacy of sectarian division, influencing its cautious, consensus-based governance. The Republic, while not directly involved in the Troubles, was deeply affected by them, fostering a strong sense of national identity and a commitment to peacebuilding. Today, cross-border cooperation under the Good Friday Agreement highlights their interconnectedness, yet their distinct political cultures persist, rooted in their separate experiences of partition and statehood.

Practical differences between the two regions extend to everyday life, from currency (the Republic uses the euro, while Northern Ireland uses the pound sterling) to education and healthcare systems. For travelers or those engaging with both regions, understanding these distinctions is crucial. For instance, while both share a common language, cultural nuances and historical sensitivities can vary significantly. Recognizing these differences fosters mutual respect and effective engagement, whether in politics, business, or personal interactions.

In conclusion, the division between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland is more than a geographical boundary—it’s a reflection of historical partition, separate governance structures, and distinct political identities. While efforts toward cooperation have bridged some gaps, the legacy of division remains a defining feature of the island’s political landscape. Navigating this complexity requires an appreciation of both regions’ unique histories and systems, offering valuable insights into the enduring impact of political choices on society.

Assessing Political Feasibility: Strategies for Measuring Policy Viability

You may want to see also

Nationalist vs. Unionist Views: Competing identities, political loyalties, influence on governance

Ireland's political landscape is deeply shaped by the historical and cultural divide between Nationalists and Unionists, a rift that traces its roots to the island's complex history of colonization, resistance, and partition. Nationalists, predominantly Catholic and concentrated in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland, advocate for a united Ireland free from British rule. Unionists, primarily Protestant and based in Northern Ireland, staunchly support maintaining ties with the United Kingdom. This division is not merely ideological but permeates governance, identity, and daily life, creating a dynamic tension that continues to influence policy and societal norms.

Consider the contrasting narratives of identity. Nationalists often draw upon a shared Gaelic heritage, emphasizing language, traditions, and a history of resistance to British dominance. Their political loyalties are directed toward parties like Sinn Féin, which campaigns for Irish reunification. Unionists, on the other hand, identify with British culture and institutions, viewing themselves as an integral part of the UK. Their political allegiances lie with parties such as the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), which prioritizes preserving the Union. These competing identities are not just historical relics but active forces shaping contemporary politics, from education policies to economic strategies.

The influence of these views on governance is particularly evident in Northern Ireland, where power-sharing arrangements under the Good Friday Agreement reflect the delicate balance between Nationalist and Unionist interests. For instance, the First Minister and Deputy First Minister roles are traditionally held by representatives from both communities, ensuring neither can dominate decision-making. However, this system is not without challenges. Deadlocks over issues like the Irish Language Act or Brexit protocols highlight how deeply entrenched these loyalties are, often paralyzing governance when compromises seem unattainable.

Practical implications of this divide extend to everyday life. Schools, neighborhoods, and even sports clubs in Northern Ireland often remain segregated along Nationalist and Unionist lines, reinforcing identities from a young age. For those navigating this landscape, understanding these dynamics is crucial. Engaging with cross-community initiatives, such as integrated education programs or shared public spaces, can foster dialogue and reduce polarization. Similarly, policymakers must prioritize inclusive policies that acknowledge both identities without alienating either side.

In conclusion, the Nationalist-Unionist divide is not merely a historical artifact but a living, breathing force that continues to shape Ireland's political and social fabric. Recognizing the depth of these competing identities and their impact on governance is essential for anyone seeking to understand or influence Ireland's future. Bridging this divide requires patience, empathy, and a commitment to shared solutions that respect the complexities of both traditions.

Stay Focused: Why Avoiding Politics Can Strengthen Your Relationships

You may want to see also

Stormont and Dáil Éireann: Regional and national parliaments, legislative differences, powers

Ireland’s political division is starkly embodied in the contrasting roles and powers of Stormont (the Northern Ireland Assembly) and Dáil Éireann (the lower house of the Irish Parliament). While both are legislative bodies, their scope, authority, and historical contexts diverge significantly. Stormont operates as a devolved regional parliament within the United Kingdom, established under the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. Its primary function is to legislate on transferred matters like health, education, and infrastructure, while reserved and excepted powers—such as foreign policy and national security—remain with Westminster. In contrast, Dáil Éireann, seated in Dublin, is the sovereign parliament of the Republic of Ireland, wielding full legislative authority over all matters within its jurisdiction, including foreign affairs, defense, and taxation. This fundamental difference in status—regional versus national—shapes their respective roles in governance.

Legislatively, Stormont and Dáil Éireann differ in structure and process. Stormont’s power-sharing mechanism, designed to balance unionist and nationalist interests, requires cross-community support for key decisions, often slowing down legislative action. This system, while fostering inclusivity, can lead to gridlock, as seen in its repeated suspensions since 1998. Dáil Éireann, however, operates under a more traditional parliamentary model, where the majority party or coalition drives legislation. This allows for quicker decision-making but can marginalize opposition voices. For instance, while Dáil Éireann can pass a budget unilaterally, Stormont’s budget requires consensus, reflecting its devolved and shared nature. These structural differences highlight the trade-offs between stability and representation in each system.

The powers of these parliaments also reveal Ireland’s political divide. Dáil Éireann’s authority extends to all aspects of governance, including international relations, exemplified by its role in Brexit negotiations and EU membership. Stormont, however, is limited to matters not reserved to Westminster, creating a dependency that underscores Northern Ireland’s unique position within the UK. For example, while Stormont manages regional health services, it cannot alter the UK’s broader healthcare policies. This asymmetry in power reflects the broader political reality: Dáil Éireann symbolizes Irish sovereignty, while Stormont navigates the complexities of a shared island and a constitutional link to Britain.

Practically, understanding these differences is crucial for policymakers and citizens alike. For instance, a health policy initiative in Northern Ireland must align with UK-wide frameworks, whereas in the Republic, Dáil Éireann can enact independent reforms. Similarly, while Dáil Éireann can pursue reunification policies, Stormont’s role is constrained by the principle of consent, requiring a majority vote in Northern Ireland. These distinctions underscore the need for nuanced engagement with each parliament’s capabilities and limitations. By recognizing their unique roles, stakeholders can better navigate Ireland’s divided political landscape and foster cooperation across the border.

Mastering the Art of Political Speeches: A Beginner's Guide to Starting Strong

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Border and Brexit Impact: Political tensions, trade, cross-border cooperation challenges

The Irish border, once a symbol of division during the Troubles, has reemerged as a flashpoint due to Brexit. The 1998 Good Friday Agreement, which brought peace to Northern Ireland, relied on both Ireland and the UK being EU members, ensuring frictionless trade and movement across the border. Brexit upended this arrangement, creating a complex web of political, economic, and social challenges.

Consider the logistical nightmare: before Brexit, goods and people flowed freely across the 310-mile border, with over 200 crossing points. Post-Brexit, the spectre of a "hard border" loomed, threatening to disrupt supply chains, increase costs for businesses, and reignite sectarian tensions. The Northern Ireland Protocol, a compromise solution, kept Northern Ireland aligned with some EU rules, effectively creating a regulatory border in the Irish Sea. While this avoided a hard border on the island, it infuriated unionist communities who felt it undermined their place in the UK.

The impact on trade has been significant. Businesses, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises, face increased bureaucracy and costs due to customs checks and regulatory divergences. This disproportionately affects sectors like agriculture and food production, which rely heavily on cross-border trade. For example, a Northern Irish dairy farmer supplying cheese to a Dublin restaurant now faces additional paperwork and potential delays, squeezing profit margins.

Cross-border cooperation, a cornerstone of the peace process, is also under strain. Joint initiatives in areas like healthcare, education, and environmental protection face uncertainty due to differing regulatory frameworks and funding sources. The very act of cooperation, once a symbol of reconciliation, is now fraught with political sensitivities. Imagine a cross-border cancer treatment program: patients from Northern Ireland accessing specialist care in Dublin could face complications due to differing healthcare systems and insurance coverage.

Addressing these challenges requires a delicate balance between respecting the democratic will of the UK to leave the EU and upholding the principles of the Good Friday Agreement. The ongoing negotiations between the UK and EU aim to find solutions that minimize disruption, protect the all-island economy, and safeguard peace. This involves finding creative ways to manage the unique circumstances of Northern Ireland, ensuring that the border remains invisible in practice, if not in theory.

Navigating Condo Politics: Strategies for Effective Communication and Conflict Resolution

You may want to see also

Power-Sharing in Northern Ireland: Consociationalism, coalition governance, stability issues

Northern Ireland’s political system is a masterclass in consociationalism, a power-sharing model designed to manage deep ethnic and religious divisions. At its core, the Good Friday Agreement (1998) established a mandatory coalition government where unionist and nationalist parties must share power. This means the First Minister and Deputy First Minister roles are jointly held, one from each community, with neither subordinate to the other. The Assembly’s d’Hondt system allocates ministerial positions proportionally based on party strength, ensuring both communities have a stake in governance. This structure isn’t just symbolic—it’s legally binding, with mechanisms like cross-community voting to prevent one group dominating the other.

However, consociationalism in Northern Ireland is no panacea. Its stability hinges on cooperation between historically antagonistic groups, a fragile premise. The system’s reliance on communal identity can entrench divisions, as parties often prioritize their base’s interests over broader societal needs. For instance, the 2017–2020 government collapse, triggered by the Renewable Heat Incentive scandal, exposed how easily disagreements can escalate into political paralysis. Moreover, smaller parties like the Alliance, which straddle the unionist-nationalist divide, are often sidelined, as the system rewards polarizing identities. This raises questions about long-term sustainability: can a model built on division ever foster genuine reconciliation?

To navigate these challenges, practical steps are essential. First, parties must prioritize cross-community engagement beyond the minimum legal requirements. Initiatives like joint policy forums or shared public projects could build trust. Second, electoral reforms could incentivize moderation. For example, introducing open-list proportional representation might encourage candidates to appeal to voters across communal lines. Third, external mediators, such as the British and Irish governments, must remain actively involved, providing a backstop during crises. Finally, civil society plays a critical role. Grassroots organizations can bridge divides by focusing on shared issues like healthcare or climate change, reducing the political focus on identity.

Despite its flaws, Northern Ireland’s model offers lessons for other divided societies. Its ability to maintain relative peace for over two decades is no small feat. Yet, the system’s success depends on continuous adaptation. As demographic shifts—like the growing number of people identifying as “neither unionist nor nationalist”—reshape the political landscape, the rigid consociational framework may need rethinking. The takeaway? Power-sharing can stabilize deeply divided societies, but it requires flexibility, external support, and a commitment to moving beyond identity politics. Without these, even the most well-designed system risks becoming a prisoner of its own structure.

Identity Politics vs. Democracy: A Threat to Unity and Governance?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Ireland is divided into two political entities: the Republic of Ireland (officially Ireland), which is a sovereign state covering approximately five-sixths of the island, and Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom.

The border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland is commonly referred to as the Irish border or the Northern Ireland border. It is approximately 310 miles (500 kilometers) long.

The Republic of Ireland is an independent nation with its own government, while Northern Ireland is governed as part of the United Kingdom. Relations between the two are shaped by historical, cultural, and political factors, with efforts to maintain peace and cooperation underpinned by agreements like the Good Friday Agreement (1998).