Gender is inherently political because it is deeply intertwined with power structures, social norms, and institutional practices that shape opportunities, identities, and inequalities. The ways in which societies define and enforce gender roles often reflect and reinforce broader systems of dominance, such as patriarchy, which historically privileges men over women and marginalizes non-binary and transgender individuals. Political decisions—from laws and policies to cultural narratives—perpetuate or challenge these gendered hierarchies, influencing access to resources, representation, and rights. For instance, debates over reproductive rights, workplace equality, and gender-based violence are not merely personal or social issues but are fundamentally political, as they involve struggles over control, autonomy, and justice. Thus, understanding gender as political highlights how it is both a site of oppression and a terrain for resistance, shaping the distribution of power and the possibilities for social change.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Policy and Legislation | Gender influences laws on reproductive rights, marriage equality, and workplace protections. |

| Representation in Politics | Women and non-binary individuals are underrepresented in political leadership roles globally. |

| Economic Disparities | Gender wage gaps persist worldwide, with women earning less than men for similar work. |

| Social Norms and Expectations | Gender roles dictate behavior, careers, and responsibilities, often limiting opportunities. |

| Healthcare Access | Gender affects access to healthcare, particularly reproductive and mental health services. |

| Violence and Safety | Gender-based violence, including domestic abuse and sexual assault, disproportionately affects women and marginalized genders. |

| Education Opportunities | Gender biases in education limit access to STEM fields and leadership roles for girls. |

| Media Representation | Gender stereotypes are perpetuated in media, influencing societal perceptions and norms. |

| Intersectionality | Gender intersects with race, class, and sexuality, compounding political and social issues. |

| Global Perspectives | Gender politics vary by country, with differing levels of equality and rights enforcement. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Gender roles and power dynamics in political institutions

Political institutions, from parliaments to cabinets, are not neutral spaces. They are arenas where gender roles and power dynamics are both reflected and reinforced. Consider this: as of 2023, women hold only 26.5% of parliamentary seats globally, despite making up roughly half of the world’s population. This disparity is not merely a numbers game; it signals deeper structural inequalities. Political institutions often operate on norms and practices historically shaped by men, for men. For instance, long working hours, aggressive debate styles, and networking in male-dominated spaces create barriers for women, who are still disproportionately responsible for unpaid care work. These institutional norms effectively exclude women, perpetuating a cycle where male perspectives dominate policy-making.

To dismantle these barriers, deliberate interventions are necessary. Quotas, for example, have proven effective in increasing women’s representation. Rwanda, with its 61% female parliament, is a testament to this. However, quotas alone are not enough. Institutional cultures must shift to accommodate diverse leadership styles. This includes rethinking meeting schedules, promoting family-friendly policies, and fostering inclusive debate formats. Practical steps could involve mandating gender-balanced committees, providing leadership training for women, and publicly tracking gender parity goals. Without such measures, political institutions risk remaining bastions of male privilege, sidelining half the population’s voices.

A comparative analysis reveals that gendered power dynamics in politics are not universal but context-specific. In Nordic countries, where gender equality is prioritized, women’s political participation is significantly higher. Sweden, for instance, has nearly 47% female parliamentarians. Contrast this with Japan, where women hold only 9.9% of parliamentary seats, and the role of cultural norms becomes clear. In Japan, traditional expectations that women prioritize family over career, coupled with a lack of institutional support, stifle female political advancement. This comparison underscores the need for context-specific strategies: what works in Sweden may not work in Japan, but both require addressing cultural and institutional biases.

Finally, the consequences of gendered power dynamics in political institutions extend beyond representation. Policies shaped predominantly by men often overlook women’s needs. For example, healthcare policies may neglect maternal health, and economic policies may ignore the gender wage gap. To counter this, political institutions must adopt a gender-responsive approach. This involves conducting gender impact assessments for all policies, ensuring women’s voices are included in decision-making, and allocating resources to address gender disparities. By doing so, political institutions can move from being part of the problem to becoming catalysts for gender equality. The challenge is not just to include women but to transform the systems that exclude them.

Understanding the Formation and Structure of Political Organizations

You may want to see also

Intersectionality: race, class, and gender in politics

Gender, race, and class are not isolated categories but intersecting axes of identity that shape political experiences and outcomes. Consider the 2020 U.S. presidential election, where Black women voters were credited with delivering key swing states despite historically facing disenfranchisement. Their turnout rate (68%) surpassed all other racial and gender groups, yet their political priorities—such as healthcare access and economic equity—remain underaddressed in mainstream policy debates. This example underscores how intersectionality reveals the compounded marginalization of specific groups, demanding a political analysis that moves beyond single-issue frameworks.

To operationalize intersectionality in political strategy, policymakers must disaggregate data by race, class, and gender. For instance, a 2019 study by the National Women’s Law Center found that while the gender wage gap for all women in the U.S. is 82 cents to a man’s dollar, Black women earn only 62 cents and Latinas 54 cents. Such granular analysis exposes how universal policies (e.g., blanket minimum wage increases) may fail to address disparities rooted in overlapping systems of oppression. Practical steps include mandating intersectional impact assessments for legislation and allocating targeted funding for communities at the margins, such as the $25 billion in Biden’s American Rescue Plan directed toward minority-owned small businesses.

A cautionary note: intersectionality is often reduced to a buzzword in political discourse, stripped of its radical potential to challenge power structures. For example, corporate diversity initiatives frequently focus on increasing representation in leadership roles without addressing systemic pay inequities or workplace harassment. To avoid tokenism, political actors must adopt a transformative approach, such as implementing pay transparency laws (as in the UK, where companies with over 250 employees must report gender pay gaps) and mandating anti-bias training that explicitly addresses racialized gender dynamics.

Comparatively, global movements like #MeToo illustrate both the promise and pitfalls of intersectional politics. While the movement amplified voices of gender-based violence survivors in the West, it initially sidelined experiences of low-income women and women of color, who face higher rates of workplace retaliation for speaking out. In contrast, India’s Dalit Women Fight movement integrates caste, class, and gender in its demands for land rights and protection from sexual violence, offering a model for coalition-building that centers the most marginalized. Such examples highlight the necessity of cross-cultural solidarity and localized strategies in intersectional political organizing.

Ultimately, treating intersectionality as a lens rather than a checklist requires continuous self-reflection and adaptation. Political parties, for instance, could institute internal audits to evaluate candidate recruitment processes, ensuring that women from working-class backgrounds or minority racial groups are not systematically excluded. By embedding intersectional principles into institutional practices—from budgeting to policy design—politics can move from symbolic gestures to structural change, addressing the layered realities of those at the intersections of race, class, and gender.

Does OkCupid Reflect Political Views in Dating Preferences?

You may want to see also

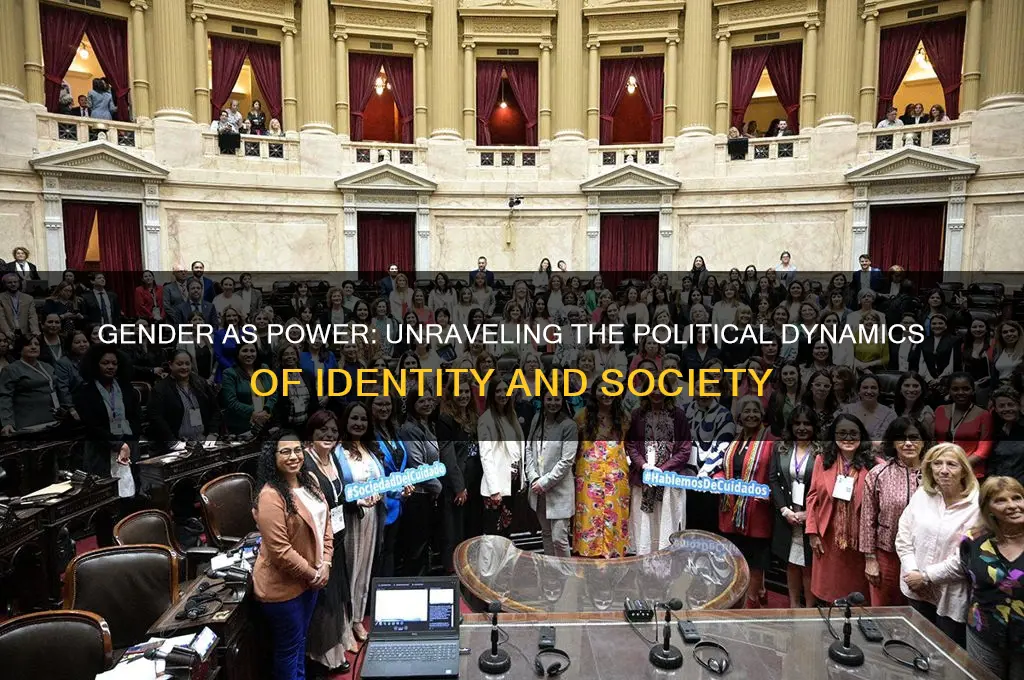

Representation of women in political leadership

Women hold only 26.5% of parliamentary seats globally, a statistic that starkly illustrates the persistent underrepresentation of women in political leadership. This disparity is not merely a numbers game; it reflects deeper systemic barriers that limit women's access to power and influence. Cultural norms, gender stereotypes, and structural biases within political institutions often conspire to keep women on the periphery of decision-making. For instance, the expectation that women should prioritize caregiving roles over public service can deter their political ambitions. Addressing this imbalance requires more than symbolic gestures; it demands deliberate policies such as gender quotas, mentorship programs, and public awareness campaigns to challenge entrenched attitudes.

Consider the case of Rwanda, where women make up 61% of the parliament, the highest proportion in the world. This achievement is no accident but the result of a post-genocide constitution that mandated a minimum of 30% female representation in decision-making bodies. Rwanda’s success demonstrates that quotas can be a powerful tool for accelerating gender parity in politics. However, quotas alone are not a panacea. They must be accompanied by efforts to address the root causes of inequality, such as unequal access to education, economic resources, and political networks. Without such comprehensive measures, quotas risk becoming a ceiling rather than a floor for women’s participation.

The benefits of women’s political leadership extend far beyond symbolic representation. Studies show that higher female representation in government is associated with increased investment in social welfare, education, and healthcare. For example, research by the World Bank found that countries with more women in parliament are more likely to allocate funds to programs that benefit families and children. This is not to suggest that women inherently govern differently, but rather that diverse leadership brings a broader range of perspectives and priorities to the table. Encouraging women’s political participation, therefore, is not just a matter of fairness but of improving governance outcomes for entire societies.

Despite progress in some regions, the path to gender parity in political leadership remains fraught with challenges. Women in politics often face disproportionate scrutiny, harassment, and media bias. A 2019 study by the Inter-Parliamentary Union found that 81.8% of female parliamentarians had experienced psychological violence during their terms. To combat this, political parties and governments must implement robust mechanisms to protect women leaders, such as anti-harassment policies and legal frameworks that penalize gender-based discrimination. Additionally, media outlets play a critical role in shaping public perceptions; they should commit to fair and unbiased coverage of female politicians, avoiding stereotypes and focusing on their qualifications and policies.

Ultimately, achieving equitable representation of women in political leadership requires a multi-faceted approach that addresses both structural and cultural barriers. It involves not only creating opportunities for women to enter politics but also fostering an environment where they can thrive. This includes educating the public about the value of gender diversity in leadership, supporting women candidates through training and resources, and holding institutions accountable for their commitments to equality. The goal is not just to increase the number of women in power but to transform the systems that have historically excluded them. As more women rise to political prominence, they challenge outdated norms and pave the way for future generations, creating a more inclusive and representative democracy.

Mastering Polite Disagreement: Effective Phrases for Respectful Arguments

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Gender-based policies and their political implications

Gender-based policies are not neutral interventions; they are inherently political, shaping power dynamics and redistributing resources in ways that reflect societal values. Consider the implementation of paid parental leave. In countries like Sweden, where parental leave is generous and gender-neutral, the policy aims to reduce gender disparities in the workplace by encouraging men to take on caregiving roles. However, in nations with shorter, gender-specific leave, such as the United States, women often bear the brunt of caregiving, reinforcing traditional gender roles. These policies don't merely address practical needs—they embed political choices about equality, family structures, and economic participation.

Analyzing the political implications requires examining who benefits and who is left behind. For instance, affirmative action policies aimed at increasing women’s representation in leadership positions are often framed as steps toward equality. Yet, they can face backlash from groups perceiving them as unfair advantages. In India, reservations for women in local governance (Panchayati Raj) have empowered millions of women but also sparked resistance from male-dominated power structures. Such policies highlight the tension between equity and equality, revealing how gender-based interventions challenge existing hierarchies and provoke political resistance.

To craft effective gender-based policies, policymakers must navigate this complexity. Start by identifying specific gaps—for example, the gender pay gap in STEM fields—and design targeted solutions, such as mentorship programs or transparent salary disclosures. Pair these with broader systemic changes, like revising hiring algorithms to eliminate bias. Caution: avoid one-size-fits-all approaches. Policies must account for intersectionality, recognizing how race, class, and sexuality compound gender disparities. For instance, a policy addressing workplace harassment should include provisions for migrant women, who face unique vulnerabilities.

Persuasively, gender-based policies are not just moral imperatives but economic and social investments. McKinsey estimates that advancing gender equality could add $12 trillion to global GDP by 2025. Yet, their success hinges on political will and public support. Advocates must frame these policies not as zero-sum games but as collective gains. For example, campaigns for menstrual equity—such as eliminating tampon taxes or providing free products in schools—have gained traction by emphasizing health, education, and economic benefits for all. This reframing shifts the narrative from "women’s issues" to societal progress.

Comparatively, the political implications of gender-based policies vary across cultures and regimes. In Nordic countries, where gender equality is a cornerstone of social democracy, such policies are widely accepted. In contrast, authoritarian regimes often use gender policies selectively to bolster legitimacy, as seen in Saudi Arabia’s lifting of the female driving ban while suppressing feminist activism. This divergence underscores how gender-based policies are tools of statecraft, reflecting and reinforcing political ideologies. Understanding these contexts is crucial for advocates and critics alike, as it reveals the interplay between gender, power, and governance.

Is Congressional Oversight Political? Examining Partisanship in Government Watchdog Roles

You may want to see also

Feminist movements and their impact on political systems

Feminist movements have fundamentally reshaped political systems by challenging the exclusion of women from public life and demanding their inclusion in decision-making processes. Historically, women’s suffrage was the first major victory, granting women the right to vote and stand for office in countries like New Zealand (1893) and the United States (1920). This shift forced political parties to address women’s concerns, from reproductive rights to workplace equality, as a matter of electoral strategy. For instance, the 19th Amendment in the U.S. not only expanded democracy but also laid the groundwork for later feminist waves to push for policy changes, such as the Equal Pay Act of 1963. Without this initial push for political representation, gender-specific issues would remain marginalized in legislative agendas.

The second wave of feminism in the 1960s and 1970s introduced intersectionality, revealing how race, class, and sexuality compound gender inequalities. This movement pressured political systems to adopt more nuanced policies, such as affirmative action and anti-discrimination laws. For example, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 in the U.S. was a direct result of feminist advocacy, ensuring pregnant women could not be fired or denied employment. However, the impact varies globally: Nordic countries like Sweden and Norway, with strong feminist influence, have implemented generous parental leave policies, while many developing nations still struggle to enforce basic protections. This highlights how feminist movements can drive systemic change but require sustained political will and cultural shifts to succeed.

Third-wave feminism and its successors have targeted structural issues within political systems themselves, such as the underrepresentation of women in leadership roles. Quotas and affirmative action have emerged as practical tools to accelerate gender parity. Rwanda, post-genocide, became a global leader with women holding over 60% of parliamentary seats due to mandated quotas. In contrast, countries without such measures, like Japan, lag significantly, with women comprising only 10% of parliament. Critics argue quotas undermine meritocracy, but evidence shows they often elevate competent women while dismantling male-dominated networks. Implementing quotas requires careful design, such as ensuring they are legally binding and accompanied by public awareness campaigns to counter backlash.

Feminist movements have also redefined political agendas by framing issues like domestic violence and sexual harassment as public, not private, matters. The #MeToo movement, for instance, forced governments to address workplace harassment through legislative reforms, such as France’s 2018 law requiring companies to prevent sexual misconduct. Similarly, feminist activism in Argentina led to the legalization of abortion in 2020, showcasing how grassroots pressure can overturn deeply entrenched policies. Yet, these victories are fragile: conservative backlashes, as seen in the U.S. Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, demonstrate the need for constant vigilance and cross-party alliances to protect gains.

Finally, feminist movements have exposed the limitations of traditional political systems in addressing gender inequality, prompting calls for transformative change. Concepts like care politics and ecofeminism challenge the male-centric focus on economic growth, advocating for policies prioritizing social reproduction and environmental sustainability. For example, Scotland’s incorporation of feminist budgeting ensures public funds address gendered needs, such as affordable childcare. While these ideas remain on the periphery in many countries, they offer a roadmap for reimagining politics beyond tokenistic inclusion. To implement such changes, policymakers must engage with feminist scholars, activists, and communities, ensuring their voices shape the agenda, not just react to it.

Navigating Workplace Politics: Strategies to Stay Positive and Productive

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Gender is political because it shapes power structures, policies, and societal norms. It influences access to resources, opportunities, and rights, often leading to systemic inequalities based on sex and gender identity.

Gender roles are political because they are socially constructed and enforced through laws, institutions, and cultural practices. Challenging or redefining these roles often involves political activism and policy changes.

Gender intersects with issues like race, class, and sexuality, creating unique experiences of oppression or privilege. This intersectionality highlights how multiple systems of power interact, making gender a central concern in political discourse.

Politics plays a crucial role in shaping gender equality through legislation, policies, and representation. Political decisions determine issues like reproductive rights, workplace equality, and protection against gender-based violence.