Since 1900, U.S. political parties have undergone significant transformations in their ideologies, structures, and electoral strategies, reflecting broader societal changes. The Democratic and Republican parties, once defined by regional loyalties—with Democrats dominant in the South and Republicans in the North—have realigned dramatically. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s accelerated the shift, as Democrats embraced progressive policies and minority rights, while Republicans increasingly aligned with conservative and Southern voters. Additionally, the rise of polarization, driven by partisan media and gerrymandering, has intensified ideological divides, making compromise more challenging. Meanwhile, third parties, though still marginalized, have gained occasional influence, and issues like globalization, immigration, and climate change have reshaped party platforms. These changes highlight the dynamic and evolving nature of U.S. political parties in response to historical and cultural forces. For more in-depth analysis, academic resources from `.edu` sites provide valuable insights into these transformations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Party Alignment | Shift from regional to ideological alignment (e.g., South shifting from Democratic to Republican). |

| Ideological Polarization | Increased polarization between Democrats and Republicans since the 1970s. |

| Role of Primary Elections | Greater influence of primary voters, leading to more extreme candidates. |

| Funding and Campaign Finance | Rise of PACs, Super PACs, and dark money since the 20th century. |

| Demographic Shifts | Democrats attracting more urban, minority, and younger voters; Republicans attracting rural and older voters. |

| Media and Communication | Increased use of social media and targeted advertising in campaigns. |

| Third Parties | Decline in third-party influence, though occasional spikes (e.g., Ross Perot in 1992). |

| Legislative Gridlock | Increased partisan gridlock in Congress, especially since the 1990s. |

| Realignment of Issues | Shifts in key issues (e.g., civil rights in the 1960s, economic inequality in the 21st century). |

| Role of Interest Groups | Growing influence of interest groups and lobbying in party politics. |

| Geographic Redistribution | Urban-rural divide becoming more pronounced in party support. |

| Party Leadership | Weakening of party leadership in Congress due to ideological factions. |

| Voter Turnout and Engagement | Fluctuations in turnout, with recent increases in youth and minority participation. |

| Globalization Impact | Parties adapting to global economic and political issues (e.g., trade, climate change). |

| Technological Advances | Use of data analytics and digital tools for voter targeting and mobilization. |

| Cultural and Social Issues | Increased focus on cultural and social issues (e.g., LGBTQ+ rights, immigration). |

Explore related products

$68.37 $74

$28.59 $30

$35.53 $61.99

What You'll Learn

Rise of the two-party system dominance

The two-party system in the United States, dominated by the Democratic and Republican parties, solidified its grip on American politics in the 20th century through a combination of structural advantages and strategic adaptations. One key factor was the winner-take-all electoral system, which incentivized voters to coalesce around the two major parties to avoid "wasting" their votes on candidates unlikely to win. This dynamic, known as Duverger's Law, effectively marginalized smaller parties and reinforced the dominance of the Democrats and Republicans. For instance, the Progressive Party, despite its significant influence in the early 1900s, failed to sustain itself as a viable third party due to this structural barrier.

Another critical element was the parties' ability to adapt to shifting political landscapes. The Democratic Party, for example, underwent a dramatic transformation in the mid-20th century as it embraced civil rights and social liberalism, attracting urban and minority voters while alienating its traditional Southern conservative base. Simultaneously, the Republican Party repositioned itself as the party of fiscal conservatism and social traditionalism, appealing to suburban and rural voters. This ideological realignment, often referred to as the "Southern Strategy," cemented the two-party system by ensuring that each party had a distinct and broad-based coalition of supporters.

The rise of primary elections also played a pivotal role in strengthening the two-party system. By allowing voters to directly select party nominees, primaries reduced the influence of party elites and made it harder for third-party candidates to gain traction. This democratization of the nomination process, however, also reinforced the dominance of the major parties, as they controlled the primary machinery and could mobilize resources more effectively than smaller parties. For example, Ross Perot's independent presidential bids in 1992 and 1996, despite their initial popularity, ultimately failed to disrupt the two-party system due to these structural and organizational barriers.

Finally, the role of media and campaign financing further entrenched the two-party system. Major parties gained disproportionate access to media coverage and fundraising networks, making it difficult for third-party candidates to compete. The Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 and subsequent Supreme Court decisions, such as *Citizens United v. FEC*, exacerbated this imbalance by allowing unlimited spending by outside groups, which overwhelmingly favored the established parties. As a result, the two-party system became not just a feature of American politics but a self-perpetuating institution, resistant to meaningful challenge from outside forces.

In practical terms, understanding the rise of the two-party system dominance requires recognizing its resilience in the face of changing demographics and political issues. While third parties and independent candidates occasionally gain attention, the structural, organizational, and financial advantages of the Democratic and Republican parties ensure their continued dominance. For those seeking to influence American politics, this reality underscores the importance of working within the existing party framework rather than attempting to build alternatives from scratch.

How Political Parties Structure and Influence Government Organization

You may want to see also

Shifts in party platforms and ideologies

The Democratic and Republican parties of today bear little resemblance to their early 20th-century counterparts. A striking example is the issue of civil rights. In 1900, the Democratic Party, particularly in the South, was the party of segregation and states' rights, while the Republican Party, the party of Lincoln, still carried the legacy of abolition. Fast forward to the 1960s, and the parties had effectively switched positions on this issue. The Democratic Party, under Lyndon B. Johnson, championed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, while many Southern conservatives, who had been Democrats, began to align with the Republican Party, a phenomenon often referred to as the "Southern Strategy."

This ideological shift can be analyzed through the lens of political realignment. The traditional bases of support for each party began to fracture and reconfigure. The Democratic Party, once dominated by conservative Southerners and progressive Northerners, saw its coalition transform. The New Deal era brought labor unions, urban voters, and ethnic minorities into the Democratic fold, gradually pushing the party's platform leftward. Conversely, the Republican Party, which had been the party of big business and established interests, started to attract socially conservative voters, particularly in the South and rural areas, who felt alienated by the Democratic Party's progressive turn.

Consider the evolution of economic policies as a case study. In the early 1900s, the Republican Party was associated with high tariffs and protectionism, appealing to industrialists and manufacturers. The Democrats, on the other hand, often advocated for more agrarian interests and lower tariffs. However, by the mid-20th century, the parties' stances on economic issues became less clear-cut. The Democratic Party, especially under Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, embraced government intervention and social welfare programs, while the Republican Party, particularly during the Reagan era, championed free-market capitalism and tax cuts. This shift illustrates how parties can adapt and redefine their ideologies to capture new voter demographics.

A persuasive argument can be made that these platform shifts are not merely random occurrences but strategic responses to societal changes. As the United States underwent industrialization, urbanization, and significant demographic transformations, political parties had to adjust their ideologies to remain relevant. For instance, the rise of the women's suffrage movement and the eventual passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920 prompted both parties to reconsider their stances on women's rights and political participation. Similarly, the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s forced a reevaluation of racial equality and justice within party platforms.

Instructively, these shifts also highlight the importance of leadership and key political figures in shaping party ideologies. Charismatic leaders can significantly influence the direction of a party. For example, Franklin D. Roosevelt's progressive policies during the Great Depression era left an indelible mark on the Democratic Party, pushing it towards a more liberal stance. Similarly, Ronald Reagan's conservative revolution in the 1980s redefined the Republican Party, emphasizing smaller government and individual liberty. These leaders not only responded to the changing needs and values of the electorate but also actively shaped them, leaving a lasting impact on the parties' platforms and ideologies.

America's Political Spectrum: Divides, Ideologies, and Shifting Landscapes

You may want to see also

Impact of civil rights movements

The civil rights movement of the mid-20th century reshaped the ideological and demographic foundations of the Democratic and Republican parties. Before the 1960s, the Democratic Party, particularly in the South, was dominated by conservative segregationists who resisted racial equality. The Republican Party, while historically associated with Lincoln and emancipation, had limited appeal to African American voters. The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, championed by Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson, marked a turning point. Johnson’s prediction that these laws would cost the Democrats the South proved accurate, as white Southern conservatives began shifting to the Republican Party, a realignment known as the "Southern Strategy."

This realignment was not immediate but unfolded over decades, accelerated by the civil rights movement’s successes. African American voters, historically disenfranchised, began to participate in elections at higher rates, overwhelmingly supporting the Democratic Party. By the 1970s, the Democratic Party had become the party of civil rights, embracing policies aimed at racial equality and social justice. Meanwhile, the Republican Party, under figures like Richard Nixon and later Ronald Reagan, capitalized on white backlash to these changes, framing their opposition as a defense of states’ rights and traditional values. This ideological shift transformed the parties’ bases, with the Democrats becoming more diverse and the Republicans increasingly identified with white conservatism.

The impact of the civil rights movement on political parties extends beyond racial demographics to policy agendas. Democrats began prioritizing issues like voting rights, affirmative action, and criminal justice reform, aligning themselves with the goals of the civil rights movement. Republicans, in contrast, often framed these policies as government overreach, appealing to voters skeptical of federal intervention. This divergence created a stark partisan divide on issues of race and equality, which persists today. For instance, debates over voter ID laws, gerrymandering, and police reform are now deeply polarized along party lines, with Democrats advocating for expanded access and Republicans often emphasizing law and order.

A practical takeaway for understanding this transformation is to examine voting patterns in presidential elections. In 1960, Dwight D. Eisenhower carried several Southern states, but by 1980, Ronald Reagan’s landslide victory included nearly every state in the former Confederacy. Conversely, African American support for Democrats rose from 50% in 1952 to over 90% in recent elections. These shifts illustrate how the civil rights movement not only changed party platforms but also reconfigured the electoral map. For educators and students, analyzing county-level voting data from 1950 to 2020 can provide concrete evidence of this realignment, offering a quantitative lens on qualitative changes.

Finally, the civil rights movement’s influence on political parties highlights the interplay between social movements and institutional politics. Movements do not merely react to political changes; they drive them. The Democratic Party’s embrace of civil rights was both a response to activism and a strategic recalibration, while the Republican Party’s shift was a calculated appeal to disaffected voters. This dynamic underscores the importance of grassroots organizing in shaping party identities. For activists today, the lesson is clear: sustained pressure on political institutions can force parties to adapt, but the outcomes are often complex, with unintended consequences like polarization and realignment.

Vladimir Putin's Political Rise: A Timeline of His Early Career

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of media and technology

The rise of mass media in the early 20th century fundamentally altered how political parties communicated with voters. Newspapers, radio, and later television became powerful tools for shaping public opinion. Parties could now disseminate their messages directly to millions, bypassing traditional local networks. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fireside chats, for instance, used radio to build a personal connection with Americans during the Great Depression, demonstrating how technology could humanize a candidate and foster trust. This shift marked the beginning of media-centric campaigning, where soundbites and imagery often overshadowed policy details.

Consider the 1960 presidential debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon, a pivotal moment in understanding media’s influence. Kennedy’s telegenic appearance and confident demeanor contrasted sharply with Nixon’s sweaty, unkempt look, swaying television viewers in Kennedy’s favor. Radio listeners, however, perceived Nixon as the winner. This example highlights how the medium itself—not just the message—can determine political outcomes. Since then, candidates have invested heavily in media training, ensuring they perform well across platforms.

The digital age has further revolutionized political communication, with social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram becoming battlegrounds for public opinion. Campaigns now employ micro-targeting, using data analytics to tailor messages to specific voter demographics. For example, during the 2016 election, the Trump campaign utilized Facebook ads to reach undecided voters in swing states with precision. This level of customization was unimaginable in the pre-internet era, when broad appeals dominated. However, this approach raises ethical concerns about privacy and the manipulation of voter behavior.

Despite its advantages, the integration of technology into politics has downsides. The 24-hour news cycle and viral content often prioritize sensationalism over substance, encouraging parties to focus on divisive rhetoric rather than policy solutions. Misinformation spreads rapidly, as seen in the proliferation of fake news during recent elections. To counteract this, voters must critically evaluate sources and fact-check claims. Tools like fact-checking websites and media literacy programs can help, but individual vigilance remains crucial.

In conclusion, media and technology have reshaped U.S. political parties by amplifying their reach, personalizing communication, and introducing new challenges. From Roosevelt’s radio chats to Trump’s tweets, each technological advancement has left an indelible mark on campaigning. As parties continue to adapt to emerging platforms, the balance between effective messaging and ethical responsibility will remain a defining issue. Understanding this evolution is key to navigating the modern political landscape.

Will Self's Political Legacy: Alive or Fading in Modern Discourse?

You may want to see also

Changes in voter demographics and alignment

The 20th century witnessed a dramatic reshuffling of voter demographics and party alignment in the United States, driven by social movements, economic shifts, and changing cultural values. One of the most significant realignments occurred during the mid-20th century, often referred to as the "New Deal realignment." Franklin D. Roosevelt's Democratic Party, with its emphasis on social welfare programs and labor rights, attracted urban, working-class voters, many of whom were immigrants or their descendants. This shift marked a departure from the earlier alignment where the Democratic Party was predominantly the party of the South and rural areas. Conversely, the Republican Party, once the party of urban industrialists, became increasingly associated with suburban and rural voters, particularly in the South, as issues like states' rights and fiscal conservatism gained prominence.

Consider the role of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s, which further accelerated demographic shifts. African American voters, historically disenfranchised in the South, began to align with the Democratic Party as it championed civil rights legislation. This realignment was not immediate, but by the 1970s, the "Solid South," once a Democratic stronghold, began to flip Republican as white Southern voters, disillusioned with federal intervention, migrated to the GOP. Meanwhile, the Democratic Party solidified its base among minority groups, including African Americans, Latinos, and Asian Americans, whose populations grew significantly in the latter half of the century.

To understand the practical implications of these shifts, examine the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections. Barack Obama's victories were fueled by a coalition of young voters, women, and racial minorities, groups that had become increasingly aligned with the Democratic Party. For instance, in 2012, Obama won 93% of the African American vote, 71% of the Latino vote, and 73% of the Asian American vote, according to Pew Research Center. This demographic alignment was a direct result of long-term trends in party positioning and policy priorities.

However, these shifts are not without cautionary tales. As parties realign, they risk alienating segments of their traditional base. For example, the Republican Party's focus on social conservatism and fiscal austerity has strained its relationship with younger voters, who tend to prioritize issues like climate change and student debt relief. Similarly, the Democratic Party's emphasis on identity politics has sometimes been criticized for neglecting the economic concerns of its working-class base. To navigate these challenges, parties must balance appealing to new demographics while maintaining the loyalty of their core constituents.

In conclusion, the changes in voter demographics and alignment since 1900 reflect broader societal transformations. From the New Deal realignment to the Civil Rights Movement and beyond, these shifts have reshaped the American political landscape. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for both parties as they seek to build sustainable coalitions in an increasingly diverse and polarized electorate. By studying these trends, political strategists and voters alike can better anticipate future realignments and their implications for governance and policy.

Understanding Political Recession: Causes, Impacts, and Global Implications

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Since 1900, the Democratic Party has shifted from a conservative, pro-business stance to a more progressive, liberal platform focused on social welfare, civil rights, and economic equality. The Republican Party, initially associated with progressive reforms under Theodore Roosevelt, has moved toward conservatism, emphasizing limited government, free markets, and social traditionalism.

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s significantly realigned U.S. political parties. The Democratic Party, under President Lyndon B. Johnson, championed civil rights legislation, leading many Southern conservatives to shift to the Republican Party. This "Southern Strategy" solidified the GOP's appeal in the South and contributed to the Democrats' focus on minority and urban voters.

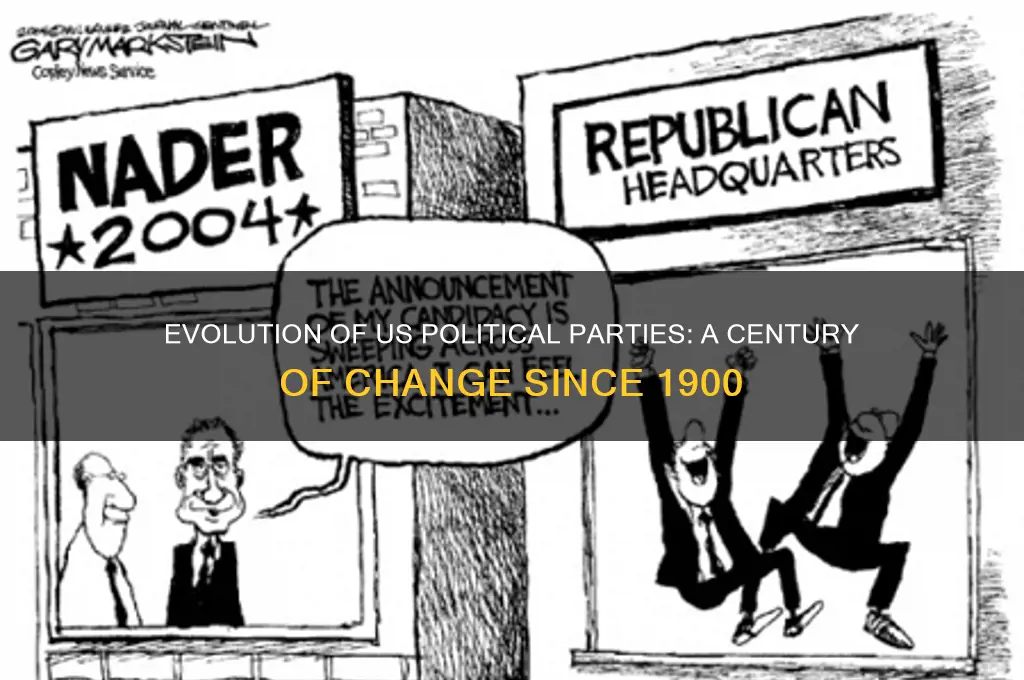

Third parties, such as the Progressive Party (1912), the Populist Party, and more recently the Libertarian and Green Parties, have influenced U.S. politics by pushing major parties to adopt their ideas. However, due to structural barriers like winner-take-all elections and ballot access laws, third parties have rarely gained significant power, maintaining the dominance of the two-party system.

Globalization has influenced U.S. political parties by shaping their stances on trade, immigration, and foreign policy. The Democratic Party has generally supported international cooperation and trade agreements, while the Republican Party has become more divided, with some factions embracing protectionism and nationalism, particularly under President Donald Trump.

Demographic shifts, including urbanization and increased immigration, have transformed the electoral base of U.S. political parties. The Democratic Party has gained support from urban, minority, and immigrant populations, while the Republican Party has maintained a stronger base in rural and suburban areas. These changes have influenced party platforms and strategies, with Democrats focusing on diversity and inclusion and Republicans emphasizing traditional values and local control.