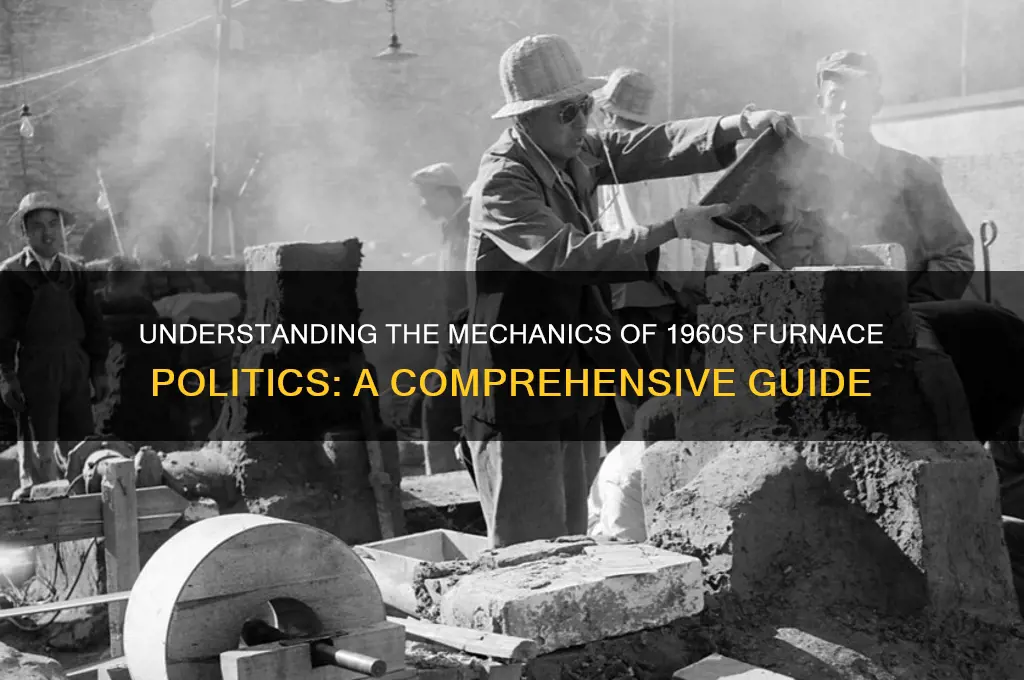

In the 1960s, furnace polishing, also known as furnace polit, was a critical process in the manufacturing of precision optical components, such as lenses and mirrors. This technique involved heating glass or other materials in a controlled furnace environment to achieve a smooth, highly reflective surface. The process relied on the principles of thermal expansion and surface tension, where the material was heated to its softening point, allowing it to flow and self-level into a polished state. Furnace polishing was widely used in industries requiring high-quality optics, including aerospace, telecommunications, and scientific instrumentation, and it played a pivotal role in advancing technologies during that era.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Fuel Combustion Process: How gas or oil ignites, generating heat for distribution

- Heat Exchanger Function: Transfers heat from flames to airflow efficiently

- Blower Mechanism: Circulates warm air through ductwork to living spaces

- Thermostat Control: Regulates temperature by activating or deactivating the furnace

- Pilot Light System: Maintains a constant flame for ignition in older models

Fuel Combustion Process: How gas or oil ignites, generating heat for distribution

The combustion process in a 1960s furnace begins with the precise mixing of fuel and air. For gas furnaces, natural gas or propane is introduced into the combustion chamber through a gas valve, regulated to maintain a specific air-fuel ratio—typically 10:1 for natural gas. In oil furnaces, an oil pump delivers atomized fuel through a nozzle, creating a fine mist that mixes with air drawn in by a blower. This mixture is critical; too much air results in inefficient burning, while too little produces soot and unburned fuel. The 1960s technology relied on mechanical controls, such as thermostats and aquastats, to modulate this process, ensuring the fuel-air blend was optimal for ignition.

Ignition is the next critical step, transforming the fuel-air mixture into heat. In gas furnaces, a pilot light—a small, continuously burning flame—was the standard method for ignition. When the thermostat called for heat, the gas valve opened, allowing the main burner to ignite from the pilot. Oil furnaces, on the other hand, used an electric igniter or a spark electrode to ignite the oil mist. The ignition process required careful timing and sequencing to prevent misfires or fuel buildup, which could lead to dangerous explosions. Safety mechanisms, such as flame sensors and limit controls, were rudimentary by today’s standards but essential for preventing hazards.

Once ignited, the combustion process generates intense heat, typically reaching temperatures between 1,400°F and 1,700°F. This heat is transferred to a heat exchanger, a series of metal tubes or coils that absorb thermal energy. In a gas furnace, the heat exchanger is designed to withstand high temperatures and prevent combustion gases from mixing with household air. In oil furnaces, the heat exchanger must also handle the byproducts of oil combustion, including soot and acids, which required regular cleaning to maintain efficiency. The efficiency of this heat transfer process was a key factor in the furnace’s overall performance, with 1960s models typically achieving 60-70% efficiency compared to modern units that exceed 90%.

The final step in the combustion process is heat distribution. A blower fan circulates air over the heat exchanger, warming it to the desired temperature before distributing it through ductwork or radiators. Thermostats controlled the temperature setpoint, cycling the furnace on and off to maintain comfort. In 1960s systems, this process was less precise than modern zoned heating, often resulting in uneven temperatures and energy waste. However, the simplicity and durability of these systems made them reliable for their time, with many still operational today with proper maintenance. Understanding this process highlights the evolution of heating technology and the importance of combustion efficiency in energy conservation.

Romanticism's Political Impact: Shaping Nations and Challenging Authority

You may want to see also

Heat Exchanger Function: Transfers heat from flames to airflow efficiently

In the 1960s, the heat exchanger in a furnace was a marvel of efficiency, designed to maximize the transfer of heat from the combustion chamber to the airflow that warms your home. This component, typically made of durable metals like steel or copper, is where the magic happens. As the burner ignites and flames engulf the combustion chamber, the heat exchanger absorbs this thermal energy. Its intricate design—often a series of tubes or coils—increases the surface area in contact with the flames, ensuring that as much heat as possible is captured. This heat is then transferred to the cool air passing over the exchanger, which is subsequently distributed through the ductwork into your living spaces. Without this efficient heat transfer, much of the energy from the fuel would be wasted, making the furnace far less effective.

Consider the process step-by-step: First, the thermostat signals the furnace to turn on, and the burner ignites the fuel (typically natural gas or oil). The flames heat the heat exchanger, which acts as a thermal bridge between the combustion chamber and the airflow. The blower motor then forces cold air from your home over the exchanger, where it rapidly warms up. This heated air is pushed through the ducts and into the rooms, raising the temperature to the desired level. The heat exchanger’s efficiency is critical here—if it’s dirty or damaged, heat transfer is compromised, leading to higher fuel consumption and uneven heating. Regular maintenance, such as cleaning and inspecting for cracks, ensures optimal performance.

A comparative analysis reveals why the 1960s heat exchanger design was so effective. Unlike earlier models, which often relied on simple metal boxes, these exchangers featured corrugated or finned surfaces to enhance heat absorption. For instance, a finned tube exchanger could increase heat transfer efficiency by up to 30% compared to a smooth-surface design. This innovation was particularly important in oil-fired furnaces, where combustion temperatures were higher and more heat needed to be captured. However, this design also had limitations: the exchanger was prone to soot buildup and corrosion, especially in humid environments. Modern furnaces address these issues with materials like stainless steel and advanced coatings, but the core principle remains the same—maximize heat transfer with minimal energy loss.

To ensure your furnace’s heat exchanger operates efficiently, follow these practical tips. First, schedule annual inspections to check for cracks or corrosion, which can lead to dangerous carbon monoxide leaks. Second, replace air filters every 1–3 months to prevent dust and debris from clogging the exchanger. Third, install a programmable thermostat to reduce unnecessary heating cycles, which can strain the exchanger. For older furnaces (pre-1980s), consider upgrading to a high-efficiency model with a secondary heat exchanger, which captures additional heat from exhaust gases. While the initial cost is higher, the energy savings and improved comfort make it a worthwhile investment. By understanding and maintaining this critical component, you can extend the life of your furnace and keep your home warm efficiently.

Overcoming Political Ignorance: Strategies for Informed Civic Engagement

You may want to see also

Blower Mechanism: Circulates warm air through ductwork to living spaces

The blower mechanism in a 1960s furnace was the unsung hero of home heating, quietly ensuring that warm air reached every corner of a house. Positioned near the furnace’s heat exchanger, this motorized fan activated once the thermostat signaled a temperature drop. Its primary function was to draw heated air from the furnace and propel it through a network of ductwork, delivering warmth to living spaces efficiently. Unlike modern systems with variable speeds, these blowers typically operated at a single, constant rate, relying on a simple on-off switch to regulate airflow. This mechanism was a marvel of its time, transforming static heat into dynamic comfort.

To understand its operation, imagine a centrifugal fan with curved blades, spinning rapidly to create a high-pressure airflow. This air was forced into the duct system, which acted as the circulatory system of the home. Proper duct design was critical; leaks or blockages could reduce efficiency by up to 30%, leaving rooms unevenly heated. Homeowners were often advised to inspect ducts annually for debris or disconnections, ensuring the blower’s efforts weren’t wasted. Additionally, the blower’s motor required occasional lubrication, typically with 10-weight non-detergent motor oil applied to the oil ports every heating season. Neglecting this maintenance could lead to overheating and premature failure.

Comparing the 1960s blower to modern systems highlights both its ingenuity and limitations. Today’s furnaces often feature variable-speed blowers that adjust airflow based on demand, reducing energy consumption and noise. In contrast, the 1960s model was a brute-force solution, either fully on or off, which could lead to temperature fluctuations and higher utility bills. However, its simplicity made it durable and repair-friendly. A homeowner with basic tools could often replace a worn belt or clean the fan blades, tasks that might require professional intervention in contemporary systems. This hands-on accessibility was a hallmark of mid-century heating technology.

For those restoring a vintage furnace, understanding the blower’s role is crucial. Start by verifying the motor’s capacitor, a common failure point, using a multimeter to check for continuity. If the blower runs continuously or not at all, this is often the culprit. Next, inspect the fan belt for cracks or looseness; a properly tensioned belt should deflect no more than ½ inch when pressed. Finally, ensure the blower wheel is free of dust and debris, as buildup can reduce airflow and strain the motor. These steps, combined with regular filter changes, can extend the life of the system and maintain its efficiency, preserving a piece of heating history while keeping your home warm.

Discovering Political Speeches: Effective Strategies for Research and Access

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.15 $18.99

Thermostat Control: Regulates temperature by activating or deactivating the furnace

In the 1960s, thermostat control was the brain behind a furnace's operation, ensuring homes remained comfortable without constant manual adjustments. This device, often a simple dial or mercury switch, monitored room temperature and signaled the furnace to turn on or off as needed. For instance, if the temperature dropped below the set point, the thermostat would activate the furnace, initiating a sequence of events: the burner ignited, the heat exchanger warmed, and the blower circulated hot air through the ducts. Once the desired temperature was reached, the thermostat would deactivate the furnace, conserving energy and maintaining a consistent indoor climate.

Consider the mechanics of a mercury bulb thermostat, a common design in 1960. As room temperature changed, the mercury inside the bulb expanded or contracted, tilting the switch to complete or break the electrical circuit. This binary action—on or off—was both reliable and straightforward, though it lacked the precision of modern digital thermostats. Homeowners could adjust the set point by turning a knob, typically calibrated in 1-degree Fahrenheit increments. For optimal efficiency, it was recommended to set the thermostat to 68°F during winter months, lowering it by 10°F when away for extended periods to save fuel.

The effectiveness of thermostat control hinged on proper placement and maintenance. Thermostats should be installed on an interior wall, away from drafts, direct sunlight, or heat sources like lamps or appliances, as these could skew temperature readings. Dust accumulation on the device or within the furnace system could also impair performance, so periodic cleaning was essential. For households with varying schedules, programmable thermostats (though rare in 1960) offered the advantage of automatically adjusting temperatures at specific times, reducing unnecessary heating.

Comparing the 1960s thermostat to its modern counterparts highlights both its limitations and ingenuity. While today’s smart thermostats use algorithms, Wi-Fi connectivity, and motion sensors to optimize heating, the 1960s model relied on mechanical simplicity and user vigilance. Its lack of proportional control meant the furnace ran at full capacity until the set temperature was reached, leading to occasional temperature overshoots. Yet, this system’s durability and ease of repair made it a staple in mid-century homes, proving that sometimes, less technology can mean more reliability.

For those restoring vintage heating systems, understanding thermostat control is key to preserving both functionality and authenticity. Original thermostats can often be recalibrated or repaired, though safety upgrades like replacing old wiring may be necessary. Modern replicas that mimic the 1960s aesthetic but incorporate digital precision offer a compromise for those seeking efficiency without sacrificing style. Regardless of the choice, the principle remains: a well-regulated thermostat is the cornerstone of a furnace’s ability to provide consistent, energy-conscious warmth.

Is 'Bore' Politically Incorrect? Exploring Language Sensitivity and Respect

You may want to see also

Pilot Light System: Maintains a constant flame for ignition in older models

In the 1960s, the pilot light system was a cornerstone of furnace operation, ensuring a constant flame for immediate ignition. This small, continuously burning flame served as the catalyst for the main burner, eliminating the need for manual lighting. Positioned near the furnace’s gas valve, the pilot light was fueled by a steady, low-pressure gas supply, typically around 1/4 to 1/2 psi, to maintain its reliability. This system was particularly vital in colder climates, where a delay in furnace ignition could lead to discomfort or even frozen pipes.

The pilot light’s simplicity was its strength. Unlike modern electronic ignitions, it relied on mechanical thermocouples or flame rectification systems to detect whether the flame was lit. If the pilot light extinguished—due to drafts, gas supply issues, or a faulty thermocouple—the gas valve would automatically shut off, preventing unburned gas from accumulating. Homeowners were advised to check the pilot light periodically, especially after power outages or maintenance, to ensure it remained operational. A common troubleshooting tip was to relight the pilot using a long match or lighter, holding the gas valve’s reset button for 30–60 seconds to allow the thermocouple to heat up.

Despite its reliability, the pilot light system had drawbacks. It consumed gas continuously, even when the furnace wasn’t in use, leading to higher energy costs. For example, a typical pilot light could burn through 300–500 cubic feet of gas per month, depending on the furnace model. This inefficiency, coupled with safety concerns over open flames, spurred the development of more advanced ignition systems in later decades. However, for 1960s homeowners, the pilot light was a trusted, straightforward solution that kept their furnaces running smoothly.

Comparatively, the pilot light system’s design highlights the evolution of heating technology. While modern furnaces use intermittent spark or hot surface igniters, the pilot light’s constant flame was a practical answer to the era’s limitations in automation and electronics. Its enduring presence in older homes today serves as a reminder of how far heating systems have come, yet it remains a functional relic for those who maintain these vintage units. For anyone servicing a 1960s furnace, understanding the pilot light’s mechanics—from gas pressure to thermocouple function—is essential to ensuring both efficiency and safety.

Is 'Moderates' a Political Term? Understanding Its Role in Modern Politics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Furnace Polit system, introduced in the 1960s, is a method of heating control designed to optimize furnace operation by regulating temperature and fuel usage efficiently.

The system uses a thermostat and a series of relays to monitor and adjust the furnace’s output, ensuring consistent indoor temperatures based on user settings.

The system was commonly designed to work with oil, coal, or natural gas, depending on the furnace model and regional availability of fuel sources.

While original parts may be hard to find, many HVAC suppliers offer compatible components or retrofits to maintain or upgrade older Furnace Polit systems.