The United States Constitution, which establishes the nation's three coequal branches of government, ascribes significant powers to Congress, the legislative branch. Article I of the Constitution enumerates the powers of Congress and the specific areas in which it may legislate. While Congress is the central law-making body, the nation's founders, mindful of the potentially corrupting effects of power, sought to limit its authority to protect individual liberty. This is achieved through the Vesting Clause, which embodies two strategies for limiting Congress's power, and the enumeration of specific powers granted to Congress, including the ability to lay and collect taxes, pay debts and borrow money, regulate commerce, coin money, establish post offices, protect patents and copyrights, establish lower courts, declare war, and raise and support an Army and Navy.

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

Enumerated powers

The US Constitution established a federalist system with powers divided between the national government and the states. The Constitution grants Congress the authority to exercise only the powers outlined within it, most of which are enumerated in Article I, Section 8. These enumerated powers are explicit and specific, and there are eighteen of them. Enumerated powers include the power to tax and spend for the general welfare and common defence, to borrow money, and to regulate commerce with states, other nations, and Native American tribes.

Congress also has the power to establish citizenship naturalization laws, bankruptcy laws, and laws that are necessary and proper to carry out the laws of the land. This is known as the Necessary and Proper Clause, which has been interpreted to mean that Congress can create any laws deemed necessary and proper for executing its specified powers. This clause has been a subject of interpretation since the Constitution's writing, with a notable Supreme Court case being McCullough v. Maryland in 1819, which ruled that Congress had the implied power to create a second national bank in Maryland.

The Constitution also enumerates Congress's power to regulate immigration and naturalization, coin money and regulate currency, establish post offices, and grant patents and copyrights to promote science and the arts. Additionally, Congress has the power to declare war and raise and regulate military forces. These powers are broad and basic, and as a result, Congress's authority to regulate interstate commerce has allowed it to regulate almost anything, as nearly everything is considered to affect interstate commerce.

While the Constitution limits Congress's powers to those enumerated within it, the broad interpretation and implied powers derived from these enumerated powers have effectively given Congress a wide range of regulatory abilities.

The Constitution's Take on Happiness and Pursuit

You may want to see also

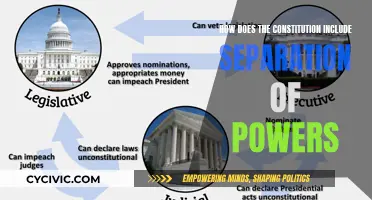

Separation of powers

The US Constitution divides the federal government into three coequal branches: Congress (the Legislative Branch), the President (the Executive Branch), and the federal courts (the Judicial Branch). Each branch has separate powers and responsibilities, and the system is designed to ensure that no one branch becomes too powerful.

Congress, as the law-making branch, has significant powers under the Constitution. Article I of the Constitution grants Congress the sole authority to enact legislation and declare war, and it can also override presidential vetoes with a two-thirds majority in both the Senate and the House of Representatives. Congress can also change the size, structure, and jurisdiction of the federal courts.

However, the Constitution also limits Congress's powers. While Congress has "all legislative powers," these are limited to those "herein granted" by the Constitution. For example, Congress cannot pass any law it wishes; it is restricted to those areas specifically enumerated in the Constitution, such as the power to lay and collect taxes, borrow money, regulate commerce, and establish uniform rules of naturalization and bankruptcy.

The separation of powers is a central principle of the US Constitution, and it is designed to protect against the accumulation of power in any one branch. Each branch has checks on the others' powers, and they are also required to cooperate to carry out certain duties. For example, the Judicial Branch acts as a check on Congress by voiding any laws that violate the Constitution, and Congress can impeach members of the Judiciary.

The system of separated powers with checks and balances helps to prevent despotism and ensure a free and limited government.

Carolina's Constitution: Still Relevant Today?

You may want to see also

Checks and balances

The US Constitution divides the government into three branches: the legislative, executive, and judicial. Each branch has specific powers and is subject to checks and balances by the others, preventing any one branch from having too much power.

The legislative branch, or Congress, has the power to make laws, approve Presidential nominations, control the budget, and impeach the President and other members of the federal judiciary. Congress can also override a Presidential veto with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate.

The executive branch, led by the President, can declare Executive Orders and veto laws passed by Congress. The President also nominates Supreme Court justices, court of appeals judges, and district court judges, who are then confirmed by the Senate.

The judicial branch, made up of the Supreme Court and other federal courts, interprets laws and rules on their constitutionality. The judiciary can declare acts of the President or laws passed by Congress unconstitutional, removing them from the law.

This system of checks and balances encourages tension and conflict between the branches, which can be beneficial in maintaining a balance of power. It also allows for congressional oversight of the executive branch, with Congress conducting hearings and investigations to ensure the President's discretion in implementing laws and making regulations is balanced.

The people of the United States also have powers given to them by the Constitution that act as checks and balances on the federal government. They can bar a constitutional amendment by Congress if three-quarters of the states refuse to ratify it and can vote for their Representatives and Senators, indirectly influencing the Judicial branch.

Russia's Constitution: Issues and Challenges

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Judicial review

The Constitution establishes the federal judiciary and the Supreme Court, but it also permits Congress to decide how to organise it. Article III, Section I of the Constitution states:

> "The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish."

Congress first exercised this power in the Judiciary Act of 1789, which created a Supreme Court with six justices and established the lower federal court system.

The best-known power of the Supreme Court is judicial review, which is the ability of the Court to declare a Legislative or Executive act in violation of the Constitution. This power is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, but it was established in the case of Marbury v. Madison (1803). The Court had to decide whether an Act of Congress or the Constitution was the supreme law of the land.

Alexander Hamilton, in Federalist No. 78, explained that the federal judiciary would have the power to declare laws unconstitutional to protect the people against abuse of power by Congress. Hamilton wrote:

> "the courts were designed to be an intermediate body between the people and the legislature, in order, among other things, to keep the latter within the limits assigned to their authority. The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts."

The Supreme Court plays a crucial role in the constitutional system of government. Its power of judicial review ensures that each branch of government recognises the limits of its power. It also protects civil rights and liberties by striking down laws that violate the Constitution and sets limits on democratic government by ensuring that popular majorities cannot pass laws that harm or take advantage of unpopular minorities.

While the Supreme Court continues to review the constitutionality of statutes, Congress and the states retain some power to influence what cases come before the Court. For example, Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution gives Congress the power to make exceptions to the Supreme Court's appellate jurisdiction, which is known as jurisdiction stripping.

When to Italicize the Preamble of the Constitution

You may want to see also

Federalism

The Constitution grants Congress enumerated powers, including the ability to lay and collect taxes, regulate commerce, coin money, establish post offices, and declare war. It also includes the Necessary and Proper Clause, also known as the Elastic Clause, which allows Congress to make all laws "necessary and proper" to carry out its enumerated powers. This clause has been interpreted broadly by the Supreme Court, which ruled in McCulloch v. Maryland that it gives the federal government certain implied powers.

Despite these enumerated powers, federalism-based limitations on Congress exist in two main ways. Firstly, the Constitution restricts Congress's authority by the scope of the powers it grants the federal government. As a result, Congress may not enact any legislation that exceeds its enumerated powers. Secondly, the Supreme Court has recognised federalism doctrines that prohibit Congress from intruding on state sovereignty, even if authorised under an enumerated power. For example, the national government may not "commandeer" state authority by forcing a state to implement federal commands.

How to Leverage Your Health for Constitutional Change

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Vesting Clause, as outlined in Article I, Section 1, vests all federal legislative powers in a representative bicameral Congress. This clause embodies two strategies for limiting Congress's power.

The Constitution limits the power of Congress by dividing it into two chambers, the Senate and the House of Representatives, each with its own rules and procedures. This bicameral structure ensures that laws must pass through multiple stages and gain broad support before being enacted.

Enumerated powers refer to the specific powers granted to Congress and listed in Article I, Section 8. By outlining what Congress can do, these powers limit the scope of congressional authority. Examples include the power to lay and collect taxes, regulate commerce, declare war, and make all laws "necessary and proper" to carry out these enumerated powers.

Federalism, though not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution, is a key concept that limits congressional power by recognising the powers of state governments. The Tenth Amendment affirms the rights of states to govern themselves, thus restricting Congress's authority over certain matters.

The separation of powers between Congress and the judiciary, particularly the Supreme Court, limits the power of Congress by providing a system of checks and balances. The Supreme Court interprets and rules on the constitutionality of laws passed by Congress, and Congress has the power to shape the judiciary through appointments and impeachment, ensuring a dialogue between the two branches.