The United States Constitution, drafted in 1787, established a federalist system with a more balanced division of powers between the federal and state governments. The Constitution grants the federal government the power to make and enforce laws, regulate foreign commerce, and declare war. The Tenth Amendment further clarifies the dynamic between federal and state powers, reserving for the states any powers not specifically granted to the federal government. This system of federalism has evolved through distinct phases, with ongoing power struggles between federal and state authorities. Supreme Court decisions, such as McCulloch v. Maryland, have played a significant role in interpreting and defining the scope of federal powers.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Powers listed in the Constitution | Make and enforce naturalization rules, regulate foreign commerce, declare war on foreign nations |

| Powers not listed in the Constitution but needed to carry out other powers | Charter a national bank |

| Powers reserved for the states | Regulate intrastate commerce, regulate public welfare and morality, tax citizens and property |

| Powers that prevent states from violating citizens' rights | Prevent states from violating privileges and immunities of citizens, depriving anyone of life, liberty, or property without due process, denying equal protection |

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

$11.99 $17.99

What You'll Learn

The Necessary and Proper Clause

The Clause expressly confers incidental powers upon Congress, and no other clause in the Constitution does so by itself. This has been interpreted as giving implied powers to Congress in addition to its enumerated powers. The Necessary and Proper Clause is the constitutional source of the vast majority of federal laws. Virtually all the laws establishing the machinery of government, as well as substantive laws ranging from anti-discrimination laws to labour laws, are enacted under the authority of the Necessary and Proper Clause.

The interpretation of the Clause has been a powerful bone of contention between political parties for several decades after the Constitution was ratified. The first practical example of this contention came in 1791, when Hamilton used the Clause to defend the constitutionality of the new First Bank of the United States, arguing that the bank was a reasonable means of carrying out powers related to taxation and the borrowing of funds. Madison, on the other hand, argued that Congress lacked the constitutional authority to charter a bank.

In the landmark case McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), the Supreme Court sided with Hamilton, holding that Congress has an implied power to establish a bank, since a bank is a proper and suitable instrument to aid in Congress's enumerated power to tax and spend. The Court ruled that federal laws could be necessary without being "absolutely necessary". The case reaffirmed Hamilton's view that legislation reasonably related to express powers was constitutional.

In 1997, the Supreme Court held in Printz v. United States that a federal law compelling state executive officials to implement federal gun registration requirements was not "proper" because it did not respect the federal/state boundaries that were part of the Constitution’s background or structure.

Understanding Impeachment: Powers, Limits, and the Constitution

You may want to see also

Federal preemption over state law

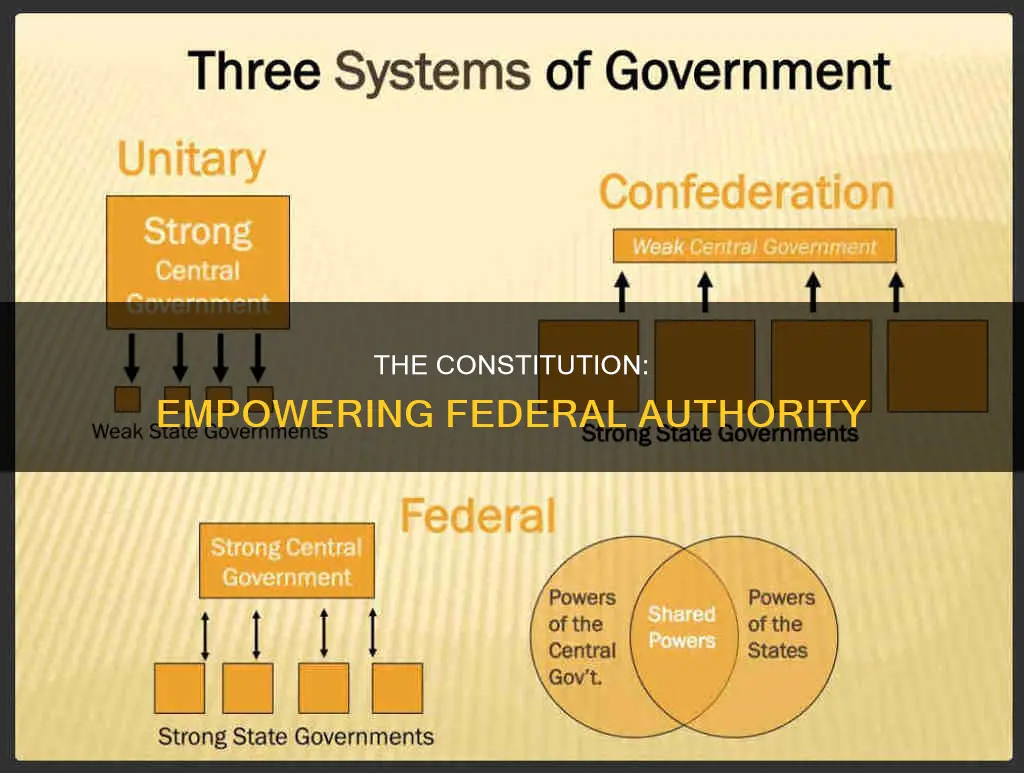

The United States government operates under a system of federalism, which divides powers between national and regional governments. The Constitution, ratified by the people in state conventions, replaced the Articles of Confederation, which functioned more like a treaty among sovereign states. The Constitution established a federalist system with more balanced powers between the federal and state governments.

The Constitution grants certain powers to the federal government, including the power to make and enforce naturalization rules, regulate foreign commerce, and declare war. The Tenth Amendment reserves powers not delegated to the federal government for the states or the people. The Necessary and Proper Clause of Article 1, Section 8 grants the federal government implied powers to carry out its express powers. The Supreme Court plays a significant role in defining these powers and has ruled that the Necessary and Proper Clause allows for federal preemption over state law.

Preemption can occur in several ways. Outright conflict happens when a state law directly opposes a federal law. Express preemption occurs when a state law contradicts a federal power. Implied preemption is more controversial and occurs when a state law prohibits or permits an act that is permitted or prohibited, respectively, by federal law. In some cases, Congress has preempted all state regulation in specific areas, such as medical devices. In other cases, federal agencies set national minimum standards while allowing states to impose more stringent requirements, as with prescription drug labels.

The Supreme Court tries to avoid preempting state laws when interpreting ambiguous rules or regulations. When state and local laws conflict, state laws typically prevail. Courts will also generally favour local ordinances over state preemption if significant interests vary between localities, unless the state statute expressly forbids it.

Planning a Visit to the National Constitution Center?

You may want to see also

Federal power to regulate immigration

The Constitution of the United States grants the federal government the power to regulate immigration. This power is rooted in national sovereignty and federalism, with the federal government enacting laws that apply across all jurisdictions in the country. The Commerce Clause in Article I, § 8, clause 3, of the Constitution gives Congress the authority to "'regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States'". This clause has been interpreted by the Supreme Court to give Congress broad powers to regulate most economic activities and many non-economic activities that could potentially impact interstate commerce.

The Naturalization Clause, which grants Congress the power to "establish an Uniform Rule of Naturalization", is another source of federal power over immigration. While determining eligibility for naturalization is not the same as having the power to prohibit immigration, it does give the federal government some authority over immigration matters. The Migration and Importation Clause, which barred Congress from outlawing the slave trade before 1808, and the power to declare war are also sometimes mentioned in discussions of congressional immigration power.

The Supreme Court has consistently upheld the federal government's exclusive power over immigration, citing national sovereignty and the need to preserve the nation's identity and unity. The Court has also recognised that the admission and exclusion of foreign nationals is a "fundamental sovereign attribute". Case law dating back to the 19th century further illustrates that immigration has long been considered a matter of national concern.

While the Constitution does not explicitly state that the federal government has the power to deny admission or remove non-citizens, the Supreme Court has interpreted it as having "plenary power" over immigration, giving it almost complete authority to decide whether foreign nationals may enter or remain in the country. This power has been used by Congress to pass, and by the Supreme Court to uphold, statutes excluding certain groups of people from immigrating to the United States.

Some, like Ilya Somin, argue that the Constitution does not contain a general federal power to restrict immigration and that the textual foundation for this power is not obvious. However, the weight of precedent and the need for uniformity in immigration laws across the country give the federal government the increased power to regulate immigration.

The Great Compromise: Uniting States, Empowering the People

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Federal power to regulate intrastate commerce

The Constitution grants the federal government increased power through the Commerce Clause, which gives Congress the authority to "regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States". This clause has been used by Congress to justify exercising legislative power over the activities of states and their citizens, leading to ongoing debates about the balance of power between federal and state governments.

The Commerce Clause has been interpreted broadly by the courts, allowing Congress to regulate intrastate commerce that substantially affects interstate commerce. This includes regulating the channels of commerce, such as the movement of goods and people across state lines, and the instrumentalities of commerce, such as railroads and other transportation industries.

In United States v. Darby Lumber Co. (1941), the Court upheld the Fair Labor Standards Act, which regulated the production of goods shipped across state lines. The Court asserted that the Tenth Amendment was not an independent limitation on congressional power. Similarly, in United States v. Wrightwood Dairy Co. (1942), the Court upheld federal price regulation of intrastate milk commerce, stating that the commerce power extends to intrastate activities that significantly impact interstate commerce.

However, in United States v. Lopez (1995), the Supreme Court attempted to curtail Congress's broad mandate under the Commerce Clause by adopting a more conservative interpretation. The Court struck down the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990, arguing that it did not pertain to "commerce" or "economic enterprise" and was not essential to regulating economic activity.

The federal government's power to regulate intrastate commerce is not unlimited and has faced challenges from states asserting their rights under the Tenth Amendment. The Rehnquist Court's New Federalism doctrine sought to strengthen individual state powers and limit congressional powers. In Gonzales v. Raich, the Court upheld federal regulation of intrastate marijuana production, marking a return to a more liberal construction of the Commerce Clause.

In conclusion, the Commerce Clause grants Congress significant power to regulate intrastate commerce that substantially affects interstate commerce. While judicial interpretations have varied, the federal government's authority in this area has generally expanded over time, often at the expense of state powers.

Revolutionary War: Is There a Constitutional Clause?

You may want to see also

The Fourteenth Amendment

The United States Constitution, which was ratified in 1787, replaced the Articles of Confederation. The Constitution established a federalist system with a more balanced division of powers between the state and federal governments. The Constitution grants the federal government the power to make and enforce laws, regulate foreign commerce, and declare war on foreign nations.

The Constitution's Separation of Powers: A True Vision?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Constitution gives the federal government the power to make and enforce naturalization rules, regulate foreign commerce, and declare war on foreign nations.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was enacted by Republicans in the Thirty-Ninth Congress, overriding President Johnson's veto. This was written into the Constitution as the Fourteenth Amendment, which prevents states from violating the privileges and immunities of their citizens.

The Necessary and Proper Clause, or Article 1, Section 8, gives Congress the power to "make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper" to carry out its delegated powers.

Federalism is the division of powers between national and regional governments, allowing states to test ideas independently.

Reserved powers are any powers that the Constitution does not assign to the federal government or disallow. These are given to the states.