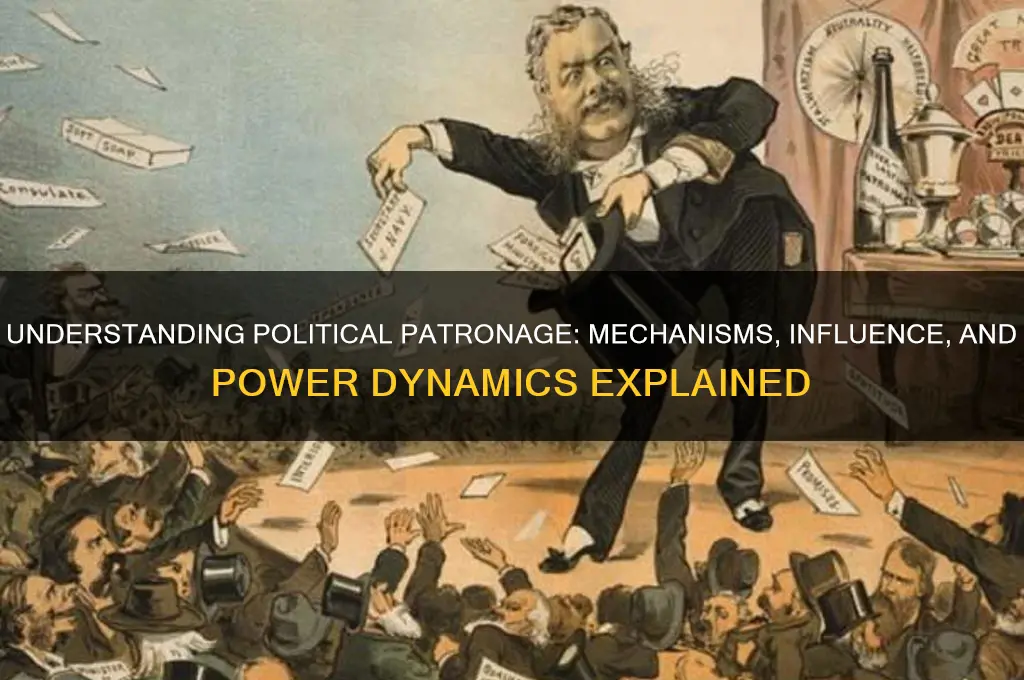

Political patronage is a system in which government officials or political parties reward their supporters, allies, and campaign contributors with jobs, contracts, or other benefits in exchange for their loyalty and continued support. This practice often involves appointing individuals to positions based on their political connections rather than their qualifications, leading to inefficiencies and a lack of meritocracy in public administration. While patronage can help consolidate political power and maintain party cohesion, it is frequently criticized for fostering corruption, nepotism, and the misuse of public resources. Understanding how political patronage operates is crucial for analyzing its impact on governance, accountability, and the equitable distribution of opportunities within a society.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | A system where political leaders distribute resources, jobs, or favors in exchange for political support, loyalty, or votes. |

| Key Players | Patrons (political leaders, parties) and Clients (supporters, constituents, or groups). |

| Resource Distribution | Includes government jobs, contracts, grants, subsidies, and access to services. |

| Exchange Mechanism | Quids pro quo: Support or loyalty in return for benefits. |

| Purpose | To maintain power, secure votes, and consolidate political influence. |

| Prevalence | Common in both democratic and authoritarian regimes, often more pronounced in developing countries. |

| Impact on Governance | Can lead to inefficiency, corruption, and unequal distribution of resources. |

| Legal Status | Often operates in a gray area, not always illegal but frequently unethical. |

| Examples | Spoils system in 19th-century U.S., clientelism in Latin America, and pork-barrel politics globally. |

| Modern Forms | Disguised as targeted welfare programs, infrastructure projects, or policy favors. |

| Countermeasures | Transparency, merit-based systems, anti-corruption laws, and civic education. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Patron-Client Relationships: Exchange of resources, favors, or support for political loyalty and influence

- Appointment Power: Distribution of government jobs to reward supporters and consolidate power

- Resource Allocation: Directing public funds or projects to loyal constituencies for political gain

- Electoral Mobilization: Using patronage networks to secure votes and maintain political dominance

- Corruption Risks: Abuse of patronage systems for personal gain, undermining transparency and accountability

Patron-Client Relationships: Exchange of resources, favors, or support for political loyalty and influence

Political patronage thrives on a delicate dance of reciprocity, where resources, favors, and support flow between patrons and clients in exchange for loyalty and influence. This transactional relationship forms the backbone of many political systems, both historical and contemporary. At its core, the patron provides tangible benefits—jobs, contracts, funding, or protection—while the client offers unwavering political backing, votes, or advocacy. This quid pro quo dynamic ensures mutual survival and advancement in the cutthroat arena of politics.

Consider the classic example of machine politics in 19th-century American cities. Political bosses like Tammany Hall’s William Tweed acted as patrons, distributing jobs and favors to immigrant communities. In return, these clients delivered votes and street-level support, solidifying the boss’s grip on power. This system, while often criticized for corruption, illustrates the efficiency of patron-client networks in mobilizing resources and people. Modern parallels exist in developing nations, where local leaders exchange infrastructure projects or welfare programs for electoral loyalty, showcasing the adaptability of this model across contexts.

However, the exchange isn’t always equitable. Patrons hold the upper hand, leveraging their resources to extract compliance. Clients, often dependent on these benefits for survival or advancement, risk exploitation. For instance, a politician might promise a community center in exchange for votes, only to delay or abandon the project once elected. This imbalance underscores the precarious nature of client loyalty, which can erode if promises go unfulfilled. To mitigate this, savvy patrons maintain credibility by delivering on at least some commitments, ensuring the relationship remains mutually beneficial.

Building a sustainable patron-client relationship requires strategic planning. Patrons must assess clients’ needs and tailor their offerings—whether it’s funding for a local school or appointments to key positions. Clients, in turn, should diversify their support base to avoid over-reliance on a single patron. For instance, a grassroots organization might align with multiple political factions, ensuring survival even if one patron falters. Transparency, while rare in such arrangements, can also strengthen trust, as seen in some Nordic countries where political funding and favors are publicly disclosed.

Ultimately, the patron-client dynamic is a double-edged sword. While it fosters political stability and resource mobilization, it can entrench inequality and undermine meritocracy. Critics argue it prioritizes loyalty over competence, as seen in systems where unqualified allies are rewarded with key posts. Yet, in fragmented societies, these networks often fill governance gaps, providing services the state cannot. Navigating this trade-off requires ethical boundaries and accountability mechanisms, ensuring patronage serves the public good rather than personal gain.

Is All Politics Dirty? Unveiling the Truth Behind the Perception

You may want to see also

Appointment Power: Distribution of government jobs to reward supporters and consolidate power

Political patronage thrives on the strategic distribution of government jobs, a practice deeply embedded in the appointment power wielded by leaders. This mechanism serves a dual purpose: rewarding loyal supporters and consolidating power by placing trusted allies in key positions. Consider the post-election scenario where a newly elected official appoints campaign managers, fundraisers, and vocal advocates to influential roles within the administration. These appointments are not merely administrative decisions but calculated moves to secure a political base and ensure policy alignment. For instance, in the United States, the "spoils system" of the 19th century exemplified this, with President Andrew Jackson replacing federal employees with his supporters, a practice that, while criticized, underscored the direct link between political loyalty and job allocation.

The process of distributing government jobs as rewards is both an art and a science. It involves identifying individuals whose skills align with the role but whose loyalty also guarantees adherence to the leader’s agenda. A practical tip for leaders is to maintain a detailed database of supporters, categorizing them by expertise, campaign contributions, and public endorsements. This allows for precise appointments that maximize both administrative efficiency and political loyalty. For example, appointing a former campaign strategist to a communications role ensures that public messaging remains consistent with the leader’s vision. However, caution must be exercised to avoid appointing unqualified individuals, as this can lead to inefficiency and public backlash, as seen in cases where patronage appointments resulted in mismanagement of public resources.

Comparatively, the use of appointment power varies across political systems. In presidential systems, the executive wields significant control over appointments, often using this power to reward supporters and sideline opponents. In contrast, parliamentary systems may distribute appointment power more broadly, involving party leaders and coalitions, which can dilute the direct reward mechanism but foster broader political stability. For instance, in the United Kingdom, while the Prime Minister appoints ministers, these choices are often influenced by party dynamics and the need to balance factions. This comparative analysis highlights that while the practice of rewarding supporters through appointments is universal, its implementation reflects the structural nuances of each political system.

A persuasive argument for limiting the scope of appointment power lies in its potential to undermine meritocracy and institutional integrity. When jobs are distributed primarily as rewards, qualified candidates may be overlooked, leading to a decline in government effectiveness. To mitigate this, some countries have introduced civil service reforms that separate political appointments from career positions, ensuring that expertise, rather than loyalty, drives key administrative roles. For example, the U.S. implemented the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act in 1883 to curb the spoils system, prioritizing competitive exams and merit-based hiring for most federal jobs. Such reforms demonstrate that while appointment power is a tool for political consolidation, its unchecked use can erode public trust and governance quality.

In conclusion, the distribution of government jobs as a reward mechanism is a cornerstone of political patronage, offering leaders a direct means to solidify their power base. By strategically appointing loyal supporters, leaders can ensure policy alignment and administrative loyalty. However, this practice requires careful calibration to balance political rewards with institutional effectiveness. Leaders must weigh the benefits of loyalty against the risks of inefficiency and public scrutiny. Practical steps include maintaining a detailed supporter database, prioritizing merit where possible, and adopting reforms that distinguish between political and career appointments. Ultimately, appointment power, when wielded judiciously, can strengthen a leader’s position without compromising governance integrity.

Does Money Buy Political Support? Exploring the Influence of Wealth

You may want to see also

Resource Allocation: Directing public funds or projects to loyal constituencies for political gain

Political patronage thrives on the strategic allocation of resources, a practice as old as governance itself. At its core, this involves directing public funds or projects to loyal constituencies, ensuring political support and cementing power. This tactic is not merely about favoritism; it’s a calculated move to reward allies, neutralize opposition, and secure future electoral victories. By funneling resources into specific areas, politicians create visible benefits that resonate with voters, fostering a sense of obligation and loyalty.

Consider the mechanics: a politician identifies a constituency that has consistently supported their party or campaign. They then prioritize infrastructure projects, such as building schools, hospitals, or roads, in that area. These projects not only address local needs but also serve as tangible proof of the politician’s commitment. For instance, in the United States, the federal government often allocates highway funds to states with key electoral votes, ensuring both economic development and political favor. This approach is not limited to developed nations; in countries like India, politicians frequently direct irrigation projects or rural electrification schemes to districts that have shown strong party allegiance.

However, this strategy is not without risks. Critics argue that it perpetuates inequality, as regions with less political clout are often neglected. For example, in Nigeria, oil-rich states receive significant federal allocations, while poorer states with weaker political representation struggle for basic amenities. This imbalance can fuel resentment and regional tensions, undermining long-term stability. To mitigate this, some governments implement formulas for resource distribution based on population, poverty rates, or development needs, though these are often circumvented by political expediency.

For those in power, the key is subtlety and timing. Resource allocation should appear responsive to public needs rather than overtly partisan. A politician might announce a new public transportation project in a loyal district just before an election, framing it as part of a broader development plan. This approach not only secures votes but also deflects accusations of favoritism. Practical tips for policymakers include conducting needs assessments to identify genuine priorities, ensuring transparency in decision-making, and balancing allocations across regions to avoid backlash.

In conclusion, resource allocation as a tool of political patronage is a double-edged sword. When executed strategically, it can solidify support and drive development in key areas. However, it requires careful management to avoid alienating other constituencies or inviting scrutiny. By understanding its mechanics and potential pitfalls, politicians can wield this tactic effectively, while citizens can better recognize and address its implications for equitable governance.

Does National Politics Still Shape Our Daily Lives?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Electoral Mobilization: Using patronage networks to secure votes and maintain political dominance

Political patronage thrives on reciprocal relationships, where resources are exchanged for loyalty. In the context of electoral mobilization, this dynamic becomes a powerful tool for securing votes and maintaining dominance. Here’s how it works: politicians leverage existing patronage networks—often built through the distribution of jobs, contracts, or favors—to activate supporters during elections. These networks are not merely transactional; they are deeply embedded in local communities, relying on personal ties and trust. For instance, in many developing democracies, local leaders or "brokers" act as intermediaries, ensuring their followers turn out to vote in exchange for continued access to resources like government jobs or infrastructure projects.

To effectively use patronage networks for electoral mobilization, politicians must follow a strategic process. First, identify key brokers who wield influence in specific regions or demographics. These brokers could be village heads, union leaders, or community organizers. Second, allocate resources judiciously—whether it’s funding for local projects, preferential treatment in government schemes, or direct financial incentives. Third, maintain consistent communication with these brokers to ensure their loyalty and ability to deliver votes. For example, in countries like India or Nigeria, politicians often rely on such networks to mobilize voters in rural areas where state presence is weak, and personal relationships dictate political behavior.

However, this strategy comes with risks and ethical considerations. Over-reliance on patronage networks can undermine democratic principles by prioritizing loyalty over merit or policy. It can also lead to voter dependency, where citizens feel compelled to vote for a candidate not out of conviction but out of fear of losing access to resources. Moreover, these networks can foster corruption, as brokers may demand larger shares of resources or engage in illicit activities to maintain their influence. A cautionary tale is the Philippines, where patronage politics has perpetuated dynastic rule and hindered equitable development.

Despite these challenges, patronage networks remain a practical tool for electoral mobilization, especially in societies with weak institutions or high levels of inequality. To mitigate risks, politicians should balance patronage with broader policy appeals, ensuring that voters are not solely reliant on personal favors. Additionally, transparency measures—such as publicly disclosing resource allocations—can reduce corruption. For instance, in Brazil, the Workers’ Party combined patronage networks with progressive policies, broadening its appeal while maintaining its base.

In conclusion, electoral mobilization through patronage networks is a double-edged sword. When used strategically, it can secure votes and maintain dominance, particularly in fragmented or resource-scarce contexts. However, it requires careful management to avoid ethical pitfalls and long-term democratic erosion. Politicians must strike a balance between leveraging personal ties and fostering genuine policy support, ensuring that patronage networks serve as a bridge to broader political engagement rather than a crutch for short-term gains.

COVID-19 Divide: How the Pandemic Became a Political Battleground

You may want to see also

Corruption Risks: Abuse of patronage systems for personal gain, undermining transparency and accountability

Political patronage, at its core, is a system where those in power distribute resources, jobs, or favors to loyal supporters, often in exchange for political backing. While it can foster cohesion and reward loyalty, it inherently carries the risk of corruption. When patronage systems are abused for personal gain, they erode transparency, accountability, and public trust. This occurs when appointments or allocations are made based on personal relationships, political loyalty, or financial contributions rather than merit, competence, or public need.

Consider the case of a local government official who awards a lucrative construction contract to a family friend’s company, bypassing competitive bidding processes. This not only diverts resources from more qualified firms but also undermines public confidence in the fairness of government operations. Such practices are not isolated incidents but systemic issues in regions where patronage networks dominate political landscapes, as seen in parts of Eastern Europe, Latin America, and Sub-Saharan Africa. The lack of oversight mechanisms exacerbates the problem, allowing abuses to go unchecked.

To mitigate these risks, governments and civil society must implement robust accountability measures. One practical step is to mandate transparent procurement processes, such as publishing all public contracts and their criteria online. Additionally, establishing independent anti-corruption bodies with the authority to investigate and prosecute abuses can act as a deterrent. For instance, countries like Singapore and Estonia have successfully reduced patronage-related corruption by combining stringent transparency laws with strong enforcement.

However, addressing corruption in patronage systems requires more than legal reforms. Cultural shifts are equally critical. Public education campaigns can raise awareness about the costs of corruption, encouraging citizens to demand integrity from their leaders. Whistleblower protections and incentives for reporting abuses can also empower insiders to expose wrongdoing without fear of retaliation. By combining structural reforms with cultural change, societies can begin to dismantle the corrosive effects of patronage abuse.

Ultimately, the fight against corruption in patronage systems is a long-term endeavor. It demands sustained political will, international cooperation, and the active participation of citizens. Without these elements, patronage will continue to be a tool for personal enrichment rather than a mechanism for equitable resource distribution. The challenge lies not in eliminating patronage entirely—which may be unrealistic—but in transforming it into a system that prioritizes public good over private gain.

Polite or Pushover: Navigating the Fine Line of Agreeing Gracefully

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political patronage refers to the practice of appointing or favoring individuals for government positions, contracts, or benefits based on their loyalty, support, or affiliation with a particular political party, leader, or group, rather than on merit or qualifications.

Political patronage often leads to inefficiency in government as it prioritizes loyalty over competence. This can result in unqualified individuals holding key positions, misallocation of resources, and reduced accountability, ultimately hindering effective governance and public service delivery.

The legality of political patronage varies by country and jurisdiction. In some places, it is explicitly prohibited, while in others, it may be tolerated or even institutionalized. Regulations, such as civil service reforms, transparency laws, and anti-corruption measures, are often implemented to curb its negative effects and promote merit-based appointments.