The development of the Second Party System in the United States, which emerged in the late 1820s and dominated American politics until the mid-1850s, was a pivotal moment in the nation's political evolution. This system, characterized by the rivalry between the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, arose from the fragmentation of the earlier Democratic-Republican Party and the growing ideological divides over issues such as states' rights, economic policies, and the role of the federal government. Jacksonian Democracy, with its emphasis on expanding suffrage and limiting federal power, contrasted sharply with the Whigs' support for national economic development, internal improvements, and a stronger central government. The rise of these two parties was also fueled by the expansion of voting rights, the emergence of a more participatory political culture, and the increasing polarization over slavery and regional interests, setting the stage for the intense political battles that would define the antebellum era.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Emergence of New Parties | The Second Party System (1828–1854) emerged with the Democratic Party (led by Andrew Jackson) and the Whig Party (formed in opposition to Jackson). |

| Rise of Mass Democracy | Expansion of voting rights to nearly all white men, regardless of property ownership, increased political participation. |

| Sectional Interests | Parties reflected regional interests: Democrats dominated the South, Whigs were stronger in the North. |

| Key Issues | Central debates included states' rights, tariffs, internal improvements, and the role of the federal government. |

| Role of Elections | Highly competitive elections with intense campaigning, including rallies, parades, and partisan newspapers. |

| Party Organization | Development of stronger party structures, including local committees, conventions, and party bosses. |

| Impact of Jacksonian Democracy | Andrew Jackson's presidency emphasized popular sovereignty, limited government, and opposition to elites. |

| Decline of Older Parties | Collapse of the First Party System (Federalists and Democratic-Republicans) due to internal divisions and changing political landscape. |

| Economic Factors | Economic policies, such as the Bank War and tariffs, shaped party platforms and voter alignment. |

| Slavery as a Divisive Issue | While not the dominant issue yet, slavery began to create tensions between Northern and Southern factions within parties. |

| Technological Advances | Improved transportation (canals, railroads) and communication (newspapers) facilitated party mobilization and outreach. |

| End of the System | The Second Party System collapsed due to irreconcilable differences over slavery, leading to the formation of the Republican Party and the Third Party System. |

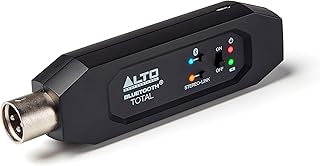

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Jackson vs. Adams: 1828 election polarized politics, highlighting democratic vs. elite governance philosophies

- Rise of Democrats: Jacksonian Democrats championed common man, states' rights, and limited federal power

- Whig Party Emergence: Whigs opposed Jackson, advocating national banks, infrastructure, and economic modernization

- Sectionalism Influence: Regional interests (North/South) shaped party platforms, especially on slavery and tariffs

- Party Organization Growth: Campaigns, newspapers, and voter mobilization transformed political participation nationwide

Jackson vs. Adams: 1828 election polarized politics, highlighting democratic vs. elite governance philosophies

The 1828 election between Andrew Jackson and John Quincy Adams marked a turning point in American politics, crystallizing the divide between democratic populism and elite governance. Jackson, a war hero and self-styled champion of the common man, ran on a platform that appealed to the growing electorate of white, property-owning males. Adams, a Harvard-educated diplomat and son of a Founding Father, embodied the establishment, advocating for centralized government and national development. This clash of ideologies transformed the election into a referendum on who should hold power: the masses or the educated elite.

Jackson’s campaign leveraged the power of grassroots mobilization, a tactic that would redefine political engagement. His supporters, often referred to as Jacksonian Democrats, framed the election as a battle against the "corrupt aristocracy" they claimed Adams represented. They used newspapers, rallies, and even parades to spread their message, targeting voters in rural areas and frontier states. Adams, meanwhile, relied on a more traditional approach, emphasizing his experience and vision for infrastructure projects like roads and canals. This contrast in campaign strategies mirrored the broader philosophical divide: Jackson’s democracy was about accessibility and representation, while Adams’ governance was about expertise and progress.

The election’s outcome—Jackson’s landslide victory—was a mandate for democratic ideals but also deepened political polarization. Jackson’s supporters saw his win as a triumph of the people over the elite, while Adams’ backers viewed it as a rejection of reasoned leadership. The campaign’s nastiness, including attacks on Jackson’s marriage and Adams’ alleged misuse of public funds, set a precedent for negative campaigning. This polarization wasn’t just about personalities; it reflected a fundamental disagreement about the role of government and who it should serve.

To understand the legacy of 1828, consider it as a blueprint for modern political divides. Jackson’s emphasis on direct democracy and suspicion of centralized power resonates in today’s populist movements, while Adams’ focus on education and infrastructure aligns with contemporary calls for technocratic governance. For practitioners of politics or students of history, the lesson is clear: elections are not just about candidates but about competing visions of society. To bridge similar divides today, focus on shared goals rather than ideological purity, and remember that polarization often stems from unaddressed fears and aspirations.

In practical terms, the 1828 election teaches us the importance of inclusive messaging. Jackson’s success hinged on making voters feel seen and heard, a tactic still relevant in diverse electorates. For modern campaigns, this means tailoring messages to specific demographics without alienating others. For educators, it underscores the need to teach political history as a study of ideas, not just events. By dissecting the Jackson-Adams contest, we equip ourselves to navigate—and perhaps heal—today’s polarized landscape.

Revitalizing Democracy: Understanding Political Party Reforms and Their Impact

You may want to see also

Rise of Democrats: Jacksonian Democrats championed common man, states' rights, and limited federal power

The emergence of the Jacksonian Democrats in the 1820s and 1830s marked a seismic shift in American politics, redefining the role of the "common man" and reshaping the balance of power between states and the federal government. At the heart of this movement was Andrew Jackson, a war hero and populist leader whose presidency (1829–1837) became the cornerstone of the Democratic Party’s early identity. Jacksonian Democrats championed three core principles: the empowerment of the common man, the defense of states’ rights, and the limitation of federal power. These ideals were not merely abstract; they were a direct response to the perceived elitism of the National Republicans, led by figures like Henry Clay and John Quincy Adams, who favored centralized authority and economic policies benefiting the wealthy.

To understand the Jacksonian appeal, consider their expansion of suffrage. By the 1820s, most states had eliminated property requirements for voting, allowing white male laborers, farmers, and artisans to participate in elections. Jacksonian Democrats capitalized on this shift, portraying themselves as the party of the people against the entrenched interests of the elite. For example, Jackson’s victory in the 1828 election was fueled by grassroots campaigns that framed him as a self-made man who understood the struggles of ordinary Americans. This populist rhetoric was paired with concrete actions, such as the rotation in office policy, which aimed to prevent political corruption by limiting the tenure of government officials. However, this inclusivity had its limits: while Jacksonian Democrats championed the "common man," they excluded women, free Blacks, and enslaved people from their vision of democracy.

States’ rights were another pillar of Jacksonian ideology, rooted in a deep suspicion of federal overreach. Jacksonians believed that power should reside with individual states, not Washington, D.C. This principle was dramatically illustrated in the Nullification Crisis of 1832–1833, when South Carolina declared federal tariffs null and void within its borders. While Jackson staunchly opposed nullification, threatening military force to enforce federal law, his actions underscored a paradox: he defended states’ rights in theory but asserted federal authority when it suited his agenda. This tension highlighted the complexities of Jacksonian politics, where states’ rights were often invoked selectively, particularly to protect Southern interests in slavery.

The commitment to limited federal power was equally central to Jacksonian Democracy. Jackson famously vetoed the rechartering of the Second Bank of the United States in 1832, arguing that it concentrated wealth and power in the hands of a few. His "Bank War" resonated with voters who saw the institution as a symbol of elitism and economic inequality. Similarly, Jackson’s dismantling of federal infrastructure projects and his opposition to internal improvements reflected a belief that such initiatives were not the government’s responsibility. This hands-off approach, however, had unintended consequences, such as stifling economic development in some regions and exacerbating regional divisions.

In practice, the Jacksonian Democrats’ principles were both transformative and contradictory. While they expanded political participation and challenged economic elites, their defense of states’ rights and limited government often served to protect slavery and delay progressive reforms. For instance, Jackson’s forceful removal of Native Americans during the Trail of Tears demonstrated how federal power could be wielded to serve state and local interests, even at the expense of human rights. This duality—championing the common man while upholding systems of oppression—defines the legacy of Jacksonian Democracy. It laid the groundwork for the modern Democratic Party but also sowed seeds of conflict that would later divide the nation.

To apply these lessons today, consider how political movements balance inclusivity with accountability. Jacksonian Democrats succeeded by appealing to the aspirations of a newly enfranchised electorate, but their narrow definition of the "common man" excluded marginalized groups. Modern parties can learn from this by crafting policies that genuinely serve all citizens, not just a majority. Additionally, the Jacksonian emphasis on states’ rights reminds us of the importance of local autonomy, but it also warns against the dangers of fragmentation. Striking this balance remains a challenge, but studying the Jacksonian era offers valuable insights into the complexities of democratic governance.

How Face Masks Sparked a Political Divide in America

You may want to see also

Whig Party Emergence: Whigs opposed Jackson, advocating national banks, infrastructure, and economic modernization

The Whig Party emerged in the 1830s as a direct response to the policies and personality of President Andrew Jackson. Jackson’s opposition to national banking, his dismantling of the Second Bank of the United States, and his skepticism toward federal investment in infrastructure galvanized a coalition of diverse opponents. These critics, who would later coalesce into the Whig Party, saw Jackson’s actions as threats to economic stability and national progress. Their platform centered on three pillars: the preservation of a national bank, federal funding for internal improvements, and a vision of economic modernization. This agenda was not merely reactive but forward-looking, aiming to harness the power of the federal government to foster growth and development.

To understand the Whigs’ advocacy for national banks, consider the economic chaos that followed Jackson’s veto of the Second Bank’s recharter in 1832. Without a central banking institution, state banks proliferated, issuing their own currencies and contributing to wild fluctuations in credit and inflation. The Whigs argued that a national bank was essential for stabilizing the economy, facilitating interstate commerce, and providing a uniform currency. For instance, they pointed to the Panic of 1837, which they blamed on Jackson’s financial policies, as evidence of the need for centralized financial oversight. Their solution was not just theoretical but practical, rooted in the belief that economic order required institutional backbone.

Infrastructure was another cornerstone of Whig policy, reflecting their commitment to what they called “internal improvements.” Whigs championed federal funding for roads, canals, and railroads, viewing these projects as engines of economic growth and national unity. They contrasted their vision with Jackson’s laissez-faire approach, which left such initiatives to private interests or state governments. A prime example was the Whigs’ support for the Cumberland Road and the Erie Canal, which they held up as models of how federal investment could transform regional economies. By advocating for infrastructure, the Whigs sought to create a physical framework for a modern, interconnected nation.

Economic modernization, in the Whig view, was inseparable from moral and social progress. They believed that a thriving economy would uplift society, reduce poverty, and promote education and culture. This vision was encapsulated in Henry Clay’s “American System,” which called for a triad of protective tariffs, a national bank, and federal infrastructure spending. Clay’s plan was not just an economic strategy but a blueprint for national greatness. Whigs argued that by investing in the nation’s material foundation, they were also investing in its future. This holistic approach distinguished them from Jackson’s Democratic Party, which they portrayed as shortsighted and parochial.

In practice, the Whigs’ agenda required a strong federal government, a stance that set them apart in an era dominated by states’ rights rhetoric. They were not afraid to use federal power to achieve their goals, whether through legislation, subsidies, or public-private partnerships. However, this approach also exposed them to criticism. Jacksonians accused them of elitism, favoring bankers and industrialists over the common man. Yet, the Whigs countered that their policies would benefit all Americans by creating jobs, lowering transportation costs, and expanding markets. Their emergence marked a pivotal moment in American politics, as they framed the debate over the role of government in economic development—a debate that continues to resonate today.

The Heart of Spartan Democracy: Where Politics Shaped a Warrior Nation

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$44.99 $49.99

Sectionalism Influence: Regional interests (North/South) shaped party platforms, especially on slavery and tariffs

The Second Party System in the United States, emerging in the 1820s and 1830s, was profoundly shaped by sectionalism—the divergence of regional interests between the North and the South. This period saw the rise of the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, each catering to distinct regional priorities. At the heart of this divide were two contentious issues: slavery and tariffs. The North, increasingly industrialized and reliant on wage labor, clashed with the South, whose agrarian economy depended on enslaved labor. These regional tensions forced political parties to craft platforms that either appeased or challenged these interests, setting the stage for decades of ideological and political conflict.

Consider the tariff issue, often dubbed the "Tariff of Abominations" by Southerners. Northern industrialists supported high tariffs to protect their growing manufacturing sector from foreign competition, particularly British imports. Southern planters, however, vehemently opposed these tariffs, as they raised the cost of imported goods while offering no direct economic benefit to their export-dependent economy. The Whigs, with their base in the North and West, championed internal improvements and protective tariffs, aligning with Northern interests. In contrast, the Democrats, while nationally focused, often sided with the South on tariffs to maintain their cross-sectional appeal. This regional economic divide forced parties to adopt clear stances, with tariffs becoming a litmus test for Northern versus Southern loyalty.

Slavery, the more explosive issue, further polarized party platforms. The North’s gradual shift toward abolitionism and free labor ideology clashed with the South’s staunch defense of slavery as essential to its way of life. The Democratic Party, under Jackson and later leaders like James K. Polk, often catered to Southern interests by supporting the expansion of slavery into new territories. The Whigs, though not uniformly anti-slavery, tended to appeal to Northern voters by focusing on economic issues rather than directly confronting slavery. This delicate balance, however, began to unravel as the moral and economic implications of slavery became impossible to ignore. The Compromise of 1850, for instance, was a temporary bandage on a deepening wound, highlighting how sectionalism forced parties to navigate a minefield of regional demands.

To understand the practical impact, examine the 1848 election. The emergence of the Free Soil Party, with its slogan "Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men," signaled a Northern backlash against the expansion of slavery. While the party did not win the presidency, its influence pushed the Whigs and Democrats to address slavery more directly in their platforms. The Democrats, led by Lewis Cass, adopted the doctrine of popular sovereignty, allowing territories to decide on slavery, a nod to Southern interests. The Whigs, meanwhile, avoided the issue altogether, focusing on economic policies. This election illustrates how sectionalism compelled parties to either embrace or evade the slavery question, shaping their identities and alienating voters across regional lines.

In conclusion, sectionalism was not merely a backdrop to the Second Party System but its driving force. The North and South’s competing interests on slavery and tariffs forced political parties to adopt distinct platforms, often at the expense of national unity. This regional polarization laid the groundwork for the eventual collapse of the system in the 1850s, as the issues of slavery and economic policy became irreconcilable. Understanding this dynamic offers a lens into how regional interests can shape—and shatter—political coalitions, a lesson as relevant today as it was in the 19th century.

Unveiling Red Eagle Politics: Understanding the Movement and Its Impact

You may want to see also

Party Organization Growth: Campaigns, newspapers, and voter mobilization transformed political participation nationwide

The emergence of the Second Party System in the United States during the early 19th century was profoundly shaped by the growth of party organization, which revolutionized political participation through campaigns, newspapers, and voter mobilization. This period, marked by the rivalry between the Democratic Party and the Whig Party, saw political parties evolve from loose coalitions into structured, nationwide machines. Campaigns became more sophisticated, leveraging rallies, parades, and personal appeals to engage voters on a scale previously unseen. Newspapers, often partisan in nature, served as the lifeblood of party communication, disseminating ideologies and mobilizing supporters across vast distances. Together, these tools transformed politics from an elite endeavor into a mass movement, democratizing participation and reshaping the nation’s political landscape.

Consider the role of newspapers in this transformation. By the 1830s, partisan newspapers had become the primary means of political education and persuasion. For instance, the *New York Tribune*, edited by Horace Greeley, was a powerful voice for the Whig Party, while the *Democratic Review* championed Jacksonian principles. These publications not only informed voters but also fostered a sense of party loyalty. Editors used rhetoric, satire, and even misinformation to sway public opinion, creating a media ecosystem that mirrored and amplified party divisions. The affordability of newspapers, coupled with their widespread distribution, ensured that political messages reached even remote areas, turning local issues into national conversations. This media-driven mobilization was a cornerstone of party organization, enabling leaders to coordinate efforts and maintain voter engagement between elections.

Campaigns during this era were equally transformative, evolving from sporadic events into highly organized, year-round activities. Party leaders like Martin Van Buren and Henry Clay pioneered techniques such as grassroots organizing, voter registration drives, and the use of campaign literature. Rallies and barbecues became staples of political outreach, blending entertainment with political messaging to attract diverse audiences. For example, the 1840 presidential campaign, dubbed the "Log Cabin and Hard Cider" campaign, used symbolism and folklore to portray William Henry Harrison as a man of the people, contrasting him with the elitist image of incumbent Martin Van Buren. These strategies not only energized voters but also created a sense of spectacle, turning elections into communal events that reinforced party identities.

Voter mobilization was the linchpin of this organizational growth, as parties sought to maximize turnout among their supporters. Techniques such as canvassing, polling, and get-out-the-vote efforts became systematic, with local party committees playing a crucial role. In urban centers, political machines like Tammany Hall in New York City used patronage and social services to build loyal voter bases. In rural areas, party networks relied on personal relationships and local leaders to ensure turnout. This mobilization was not without controversy, as accusations of voter fraud and coercion were common. However, the sheer scale of participation it achieved marked a turning point in American democracy, as millions of citizens became active participants in the political process.

The takeaway from this period is clear: the growth of party organization through campaigns, newspapers, and voter mobilization was not merely a byproduct of the Second Party System but its driving force. These innovations democratized politics, breaking down barriers of geography, class, and education to engage a broader electorate. While the methods were often partisan and sometimes manipulative, they laid the groundwork for modern political campaigning. Understanding this history offers valuable insights into the enduring power of organization in shaping political outcomes, reminding us that the tools of engagement—whether print media or grassroots rallies—remain essential to fostering civic participation.

Effective Political Action Strategies: Mobilizing Change in Today's Democracy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Second Party System (1828–1854) was a period in U.S. history dominated by the Democratic Party, led by Andrew Jackson, and the Whig Party, which emerged in opposition to Jacksonian policies.

Andrew Jackson's presidency (1829–1837) polarized American politics, with his policies on banking, states' rights, and Native American removal creating sharp divisions. This led to the consolidation of the Democratic Party and the formation of the Whig Party as its primary opposition.

The Bank War, centered on Jackson's opposition to the Second Bank of the United States, became a defining issue. Jackson's veto of the Bank's recharter and his dismantling of its power rallied supporters and opponents, solidifying party lines between Democrats and Whigs.

Regional differences, particularly between the North and South, shaped party alignments. Democrats drew strong support from the South and West, while Whigs were more influential in the North and among urban and industrial interests.

The Second Party System collapsed due to irreconcilable differences over slavery, especially after the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854). This led to the decline of the Whigs and the rise of the Republican Party, marking the beginning of the Third Party System.