The Reconstruction era following the American Civil War was a pivotal yet deeply flawed period in U.S. history, marked by significant political failures that undermined its goals of rebuilding the South and ensuring civil rights for formerly enslaved African Americans. Despite early legislative achievements, such as the passage of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, Reconstruction ultimately faltered due to entrenched racial animosity, weak federal enforcement, and the rise of white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan. Politically, the Compromise of 1877 signaled the era's demise, as Northern Republicans abandoned their commitment to Southern Black citizens in exchange for political power, allowing Democratic Redeemers to regain control of Southern state governments and institute Jim Crow laws. These failures not only betrayed the promise of equality but also entrenched systemic racism, leaving a legacy of disenfranchisement and segregation that would persist for decades.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Lack of Federal Enforcement | Despite the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments, the federal government failed to consistently enforce these protections, allowing Southern states to circumvent them through tactics like poll taxes, literacy tests, and violence. |

| Rise of White Supremacy Groups | Groups like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) terrorized Black Americans and Republicans, suppressing political participation and undermining Reconstruction efforts. |

| Compromise of 1877 | This compromise effectively ended Reconstruction by withdrawing federal troops from the South, allowing Democrats to regain control and implement Jim Crow laws. |

| Supreme Court Decisions | Landmark cases like Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) upheld segregation, while others limited the federal government's power to protect civil rights. |

| Economic Exploitation | Black Americans were often trapped in sharecropping and debt peonage systems, limiting their economic independence and political influence. |

| Disenfranchisement | Southern states enacted laws and constitutional amendments to disenfranchise Black voters, effectively reversing the gains of Reconstruction. |

| Weak Republican Leadership | Post-Lincoln presidents like Andrew Johnson and Rutherford B. Hayes lacked the political will or ability to sustain Reconstruction policies. |

| Northern Apathy | As time passed, Northern support for Reconstruction waned, leading to reduced federal intervention and resources. |

| State-Level Resistance | Southern states actively resisted federal authority, passing "Black Codes" and other laws to maintain white supremacy. |

| Lack of Land Redistribution | Failure to redistribute land to freed slaves left them economically vulnerable and dependent on former slaveholders. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Black disenfranchisement through Jim Crow laws and poll taxes

The Reconstruction Era, which followed the Civil War, was a period of immense political and social transformation in the United States. However, its promise of equality and citizenship for African Americans was short-lived, largely due to the systemic disenfranchisement that emerged through Jim Crow laws and poll taxes. These measures, implemented primarily in the Southern states, were designed to circumvent the 15th Amendment, which granted Black men the right to vote. By understanding the mechanisms and impacts of these laws, we can grasp how Reconstruction’s political ideals were systematically undermined.

Jim Crow laws, named after a minstrel show character, were state and local statutes that enforced racial segregation in the South. These laws were not merely about separation; they were tools of political control. For instance, literacy tests, grandfather clauses, and poll taxes were used to create barriers to voting. Poll taxes, in particular, required voters to pay a fee before casting their ballot. While seemingly neutral, these taxes disproportionately affected African Americans, many of whom lived in poverty due to systemic economic oppression. In Alabama, for example, the poll tax of $1.50 in the late 19th century (equivalent to about $45 today) was a significant financial burden for Black families struggling to make ends meet. This economic barrier effectively excluded them from the political process, ensuring white dominance in state legislatures.

The enforcement of Jim Crow laws was further bolstered by intimidation and violence. White supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan terrorized Black communities, making it dangerous to even attempt to vote. The federal government’s failure to intervene effectively allowed these practices to flourish. For example, in the 1876 presidential election, disputed results in Southern states led to the Compromise of 1877, which removed federal troops from the South and effectively ended Reconstruction. This withdrawal left African Americans vulnerable to state-sanctioned disenfranchisement, as local authorities had free rein to enforce Jim Crow laws without federal oversight.

The long-term consequences of these measures were profound. By the early 20th century, Black voter turnout in the South had plummeted to near zero in some states. Mississippi’s 1890 constitution, which included a poll tax and literacy test, reduced Black voter registration from over 70% to less than 6% within a decade. This political exclusion perpetuated racial inequality, as elected officials had no incentive to address the needs of African American communities. The legacy of these laws persisted until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which finally outlawed discriminatory voting practices.

To combat such disenfranchisement today, it is crucial to study these historical tactics and their modern equivalents. Voter ID laws, gerrymandering, and efforts to restrict mail-in voting echo the spirit of Jim Crow laws, targeting marginalized communities. By learning from Reconstruction’s failures, we can advocate for policies that protect voting rights and ensure that political participation remains a cornerstone of democracy. The fight against disenfranchisement is ongoing, and understanding its roots is the first step toward meaningful change.

Mastering Polite Boundaries: How to Avoid Hugs Gracefully and Respectfully

You may want to see also

Weak federal enforcement of civil rights protections

The federal government's failure to enforce civil rights protections during Reconstruction was a critical factor in its political unraveling. Despite the passage of landmark legislation like the 14th and 15th Amendments, which guaranteed citizenship, due process, and voting rights to African Americans, the federal government lacked the will and mechanisms to ensure these rights were respected at the state level. Southern states quickly devised strategies to circumvent federal law, such as poll taxes, literacy tests, and grandfather clauses, which effectively disenfranchised Black voters. The federal response was tepid at best, with President Andrew Johnson openly opposing Reconstruction efforts and later administrations prioritizing reconciliation with the South over the enforcement of civil rights.

Consider the Enforcement Acts of 1870 and 1871, designed to combat the Ku Klux Klan and protect Black voters. While these laws provided federal tools to prosecute civil rights violations, they were inconsistently applied and often ignored by local authorities sympathetic to white supremacist causes. The Supreme Court further weakened these protections by narrowly interpreting federal power in cases like *United States v. Cruikshank* (1875), which ruled that the Constitution did not grant the federal government authority to intervene in cases of private violence, even when it was racially motivated. This legal and political inertia allowed Southern states to systematically erode the gains of Reconstruction, leaving African Americans vulnerable to violence, intimidation, and legal discrimination.

A comparative analysis highlights the stark contrast between federal enforcement during Reconstruction and later civil rights movements. During the 1950s and 1960s, the federal government, under presidents like Eisenhower and Kennedy, deployed federal troops and marshals to enforce desegregation orders, as seen in the Little Rock Nine crisis. This aggressive intervention was absent during Reconstruction, where federal troops were gradually withdrawn from the South, leaving African Americans without protection. The lesson here is clear: without robust federal enforcement, even the most progressive legislation remains ink on paper, powerless to effect real change.

To understand the practical implications, imagine a Black farmer in post-Reconstruction Mississippi attempting to exercise his right to vote. He faces a web of obstacles: a poll tax he cannot afford, a literacy test designed to be failed, and the ever-present threat of violence from white supremacist groups. When he seeks federal assistance, he finds no recourse, as local officials are complicit in the denial of his rights, and federal authorities are either unwilling or unable to intervene. This scenario was not an anomaly but the norm, illustrating how weak federal enforcement rendered civil rights protections meaningless for millions of African Americans.

In conclusion, the failure of federal enforcement during Reconstruction was not merely a policy oversight but a deliberate abandonment of responsibility. It allowed the South to revert to a system of racial hierarchy, undoing the progress made during Reconstruction. This history serves as a cautionary tale: civil rights legislation is only as strong as the mechanisms in place to enforce it. Without a committed federal government willing to confront local resistance, even the most well-intentioned laws will falter, leaving marginalized communities to bear the consequences.

Norway's Political Stability: A Model of Consistency and Peaceful Governance

You may want to see also

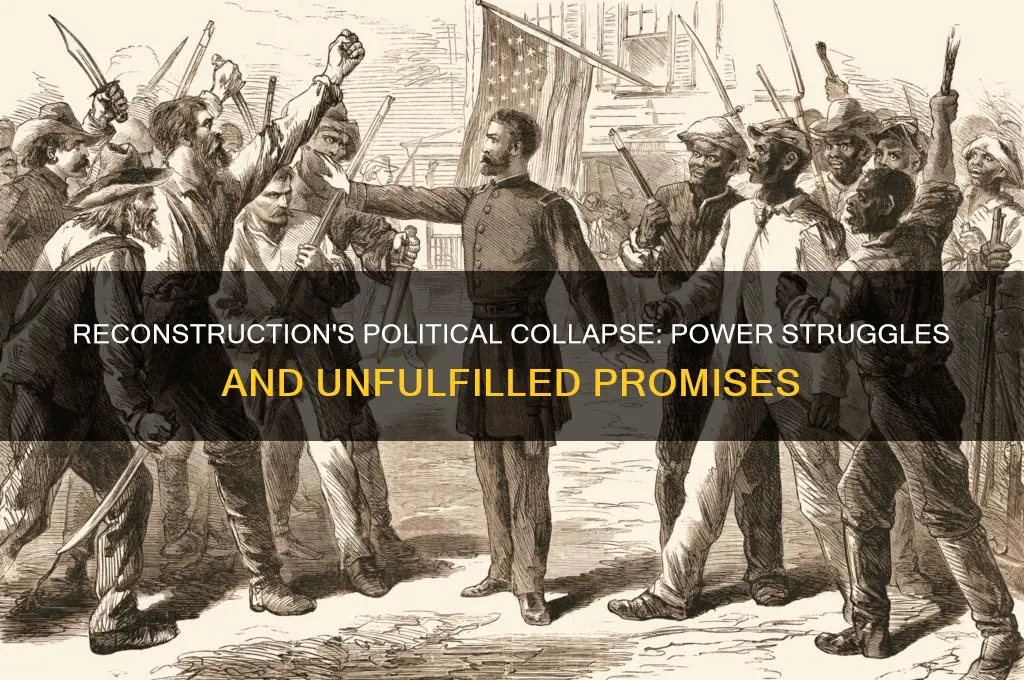

Rise of white supremacist groups like the KKK

The resurgence of white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) during Reconstruction was a direct response to the political and social upheaval caused by the abolition of slavery and the enfranchisement of African Americans. As Southern states were forced to ratify the 14th and 15th Amendments, granting citizenship and voting rights to Black men, many white Southerners felt their power slipping away. The KKK, founded in 1865 in Pulaski, Tennessee, emerged as a violent, secretive organization dedicated to maintaining white dominance through intimidation, terror, and murder. Their targets were not only Black citizens but also white Republicans, Northerners, and anyone who supported Reconstruction efforts. This wave of violence effectively suppressed Black political participation, undermining the very foundations of Reconstruction.

Consider the mechanics of how the KKK operated to achieve its goals. Members, often disguised in white hoods and robes, carried out nighttime raids, lynchings, and arson attacks to instill fear in Black communities. For example, in the 1868 election, the KKK and similar groups used violence to prevent Black voters from casting ballots, ensuring Democratic victories in several Southern states. This systematic terror campaign was not random but strategically designed to dismantle Reconstruction governments and restore white supremacy. By targeting local leaders, teachers, and politicians, the KKK sought to cripple the infrastructure of Black progress and reassert white control over Southern society.

The rise of the KKK also highlights the failure of federal authorities to enforce Reconstruction policies effectively. Despite the passage of the Enforcement Acts in 1870 and 1871, which criminalized conspiracy to deprive citizens of their rights, the federal government struggled to prosecute KKK members due to local juries sympathetic to their cause. President Ulysses S. Grant’s use of military force in South Carolina, Mississippi, and other states temporarily suppressed Klan activity, but the withdrawal of federal troops in the late 1870s left Black communities vulnerable once again. This lack of sustained federal intervention allowed white supremacist groups to regroup and intensify their efforts, ultimately contributing to the collapse of Reconstruction governments across the South.

To understand the long-term impact of the KKK’s rise, examine how their actions shaped the political landscape for decades. By the 1870s, the combination of violence, economic coercion, and political manipulation had effectively disenfranchised Black voters and dismantled biracial governments. The Compromise of 1877, which ended federal support for Reconstruction, marked the triumph of white supremacist forces. The legacy of the KKK’s terror campaign is evident in the Jim Crow laws that followed, institutionalizing racial segregation and suppressing Black political power until the civil rights movement of the 20th century. The failure to crush these groups during Reconstruction ensured that their ideology and tactics would persist, casting a long shadow over American history.

In practical terms, the rise of the KKK during Reconstruction serves as a cautionary tale about the fragility of political progress in the face of organized resistance. To prevent such backsliding, modern efforts to combat white supremacy must include robust legal enforcement, community education, and sustained political will. For instance, organizations like the Southern Poverty Law Center track extremist groups and advocate for policies to counter their influence. Individuals can support these efforts by staying informed, reporting hate crimes, and engaging in local activism. The lesson from Reconstruction is clear: without vigilant action, gains in equality can be swiftly eroded by those who seek to preserve systems of oppression.

Nepotism Beyond Politics: Exploring Favoritism in Industries and Society

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$14.59 $25.99

Compromise of 1877 ending Reconstruction prematurely

The Compromise of 1877 marked a pivotal moment in American history, effectively ending Reconstruction and sealing the fate of the South’s political and social landscape for decades. This backroom deal, struck to resolve the disputed 1876 presidential election between Rutherford B. Hayes and Samuel J. Tilden, prioritized Northern political and economic interests over the rights and protections of newly freed African Americans. In exchange for Hayes’s presidency, Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South, the last remaining safeguard against the resurgence of white supremacist regimes. This compromise was not merely a political maneuver; it was a betrayal of the Reconstruction’s promise to rebuild the South on principles of equality and justice.

Consider the immediate consequences of this agreement. With federal troops removed, Southern states were free to enact Black Codes and Jim Crow laws, systematically disenfranchising African Americans and reversing hard-won civil rights gains. The Compromise of 1877 did not just end Reconstruction—it legitimized the South’s return to a racial hierarchy, ensuring that the federal government would turn a blind eye to the violence and oppression that followed. This was not a failure of policy but a deliberate abandonment of moral responsibility, as Northern elites prioritized reconciliation with the South over the protection of its most vulnerable citizens.

To understand the gravity of this compromise, examine the contrast between its intent and its outcome. Ostensibly, the deal aimed to heal the nation’s divisions and stabilize its political system. In reality, it entrenched racial inequality and postponed the struggle for civil rights by nearly a century. The Compromise of 1877 serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of political expediency over justice. It underscores how short-term compromises can have long-term, devastating consequences, particularly when they undermine the rights of marginalized communities.

Practically speaking, the Compromise of 1877 offers a critical lesson for modern policymakers: true reconciliation cannot come at the expense of justice. When negotiating political settlements, leaders must prioritize the protection of fundamental rights over partisan or economic interests. For historians and educators, this event highlights the importance of scrutinizing the hidden costs of political deals. By studying the Compromise of 1877, we can better recognize and resist similar trade-offs in contemporary politics, ensuring that history’s mistakes are not repeated.

Democracy as a Political Institution: Structure, Function, and Impact

You may want to see also

Southern Democrats regaining political control in the South

The Reconstruction Era, intended to rebuild the South and integrate freed slaves into American society, ultimately saw Southern Democrats reclaim political dominance, undermining its goals. This resurgence was not a sudden event but a calculated, multi-faceted strategy. One key tactic was the exploitation of racial tensions. Southern Democrats, often former Confederates, capitalized on white Southerners' fears of Black political and economic power. They portrayed Republican Reconstruction policies as an imposition of Northern values and a threat to traditional Southern culture, effectively rallying white voters under a banner of resistance.

"Redeemer" governments, as they called themselves, systematically disenfranchised Black voters through poll taxes, literacy tests, and violent intimidation. This suppression, coupled with the Supreme Court's 1875 ruling in *United States v. Cruikshank*, which limited federal intervention in state affairs, effectively nullified the political gains Black Americans had made during Reconstruction.

The economic landscape also favored the return of Democratic control. The South's economy, devastated by the war, relied heavily on agriculture. Southern Democrats, often landowners themselves, championed policies favoring planters and opposed federal aid for freedmen, ensuring economic dependence and limiting opportunities for Black economic advancement. This economic stranglehold further solidified their political power.

The rise of paramilitary groups like the Ku Klux Klan played a crucial role in this power grab. These groups employed terror tactics, including lynchings and arson, to intimidate Black voters and Republican officials. The federal government's inability to effectively suppress these groups allowed them to operate with impunity, creating a climate of fear that discouraged political participation among Black Americans.

The withdrawal of federal troops from the South in 1877 marked a turning point. Without federal oversight, Southern Democrats were free to consolidate their power. They dismantled Reconstruction-era reforms, enacting Jim Crow laws that institutionalized segregation and disenfranchisement. This legal framework ensured Democratic dominance for decades, effectively reversing the progress made during Reconstruction and relegating Black Americans to second-class citizenship.

The failure of Reconstruction to prevent Southern Democrats from regaining control highlights the fragility of political change in the face of entrenched interests and systemic racism. It serves as a stark reminder that true equality requires not only legal reforms but also economic empowerment, protection from violence, and a sustained commitment to dismantling discriminatory structures. The legacy of this failure continues to shape American politics and society today, underscoring the ongoing struggle for racial justice.

Mastering Political Thinking: Strategies for Navigating Amazon's Complex Landscape

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The main political failures of Reconstruction included the inability to fully protect the civil rights of African Americans, the rise of white supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan, and the withdrawal of federal support for Reconstruction policies, culminating in the Compromise of 1877.

The Compromise of 1877 led to the withdrawal of federal troops from the South, effectively ending Reconstruction and allowing Southern states to disenfranchise African Americans and establish Jim Crow laws without federal intervention.

Reconstruction governments collapsed due to widespread corruption, economic instability, and the lack of support from Northern politicians, coupled with violent resistance from white Southerners who sought to regain political control.

The Supreme Court undermined Reconstruction through decisions like *United States v. Cruikshank* (1875) and *Plessy v. Ferguson* (1896), which limited federal power to enforce civil rights and upheld racial segregation, weakening protections for African Americans.

President Rutherford B. Hayes played a key role by agreeing to the Compromise of 1877, which removed federal troops from the South in exchange for his election victory, effectively abandoning federal support for Reconstruction and allowing Southern states to suppress African American rights.

![A Short History of Reconstruction [Updated Edition] (Harper Perennial Modern Classics)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81PyArFtm6L._AC_UY218_.jpg)