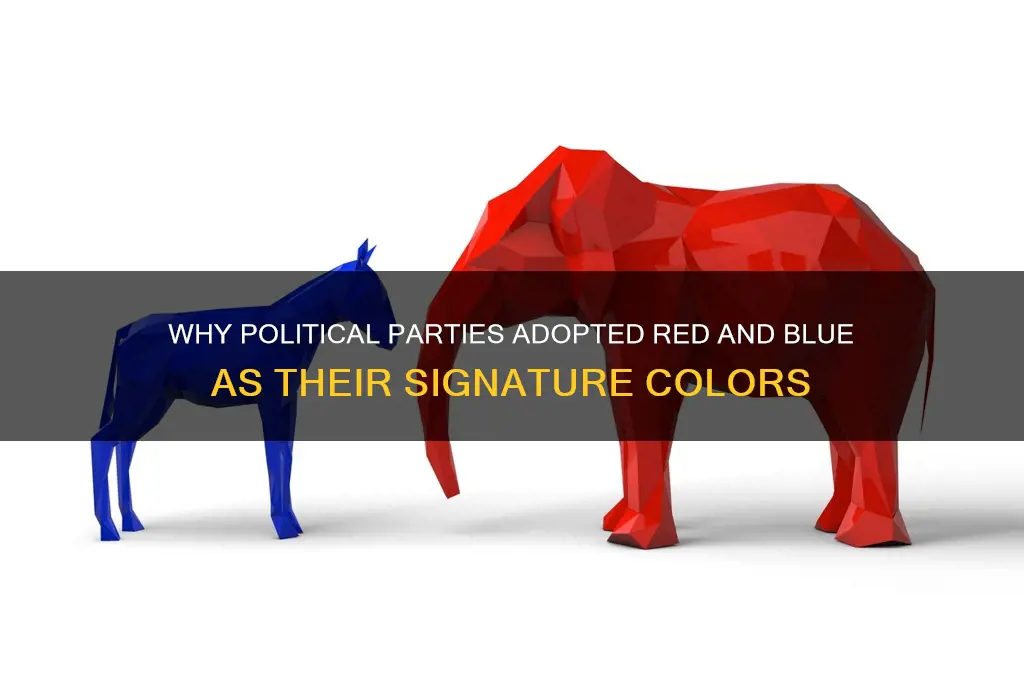

The designation of red and blue as the primary colors for political parties in the United States is a relatively recent phenomenon, with its roots tracing back to the 2000 presidential election. Initially, the color assignments were not standardized, and news networks used various colors to represent different parties. However, during the contentious 2000 election, major media outlets began consistently using blue to represent Democratic states and red to represent Republican states on electoral maps. This color scheme gained widespread acceptance, and over time, it became the standard way to visually distinguish between the two major political parties in the U.S., shaping the way Americans perceive and discuss political affiliations today.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Origin of Color Designation | The association of red and blue with political parties in the U.S. dates back to the 1976 presidential election, when news networks used colored maps to represent candidate victories. |

| Initial Color Assignment | In 1976, NBC used blue for Jimmy Carter (Democrat) and red for Gerald Ford (Republican), but the colors were not consistent across networks or elections until later. |

| Standardization | The color scheme became standardized during the 2000 presidential election, when media outlets consistently used blue for Democrats and red for Republicans, creating the "red state vs. blue state" concept. |

| Psychological and Cultural Factors | Red is often associated with conservatism, strength, and urgency, while blue is linked to liberalism, calmness, and trust, though these associations vary culturally. |

| Global Variations | In many countries, red is associated with left-leaning or socialist parties (e.g., Europe), while blue is tied to conservative parties, contrasting with the U.S. designation. |

| Media Influence | Television and digital media played a significant role in solidifying the red-blue color scheme, making it easier for viewers to identify party affiliations on election maps. |

| Party Branding | Over time, the parties themselves adopted these colors for branding, with Democrats using blue and Republicans using red in campaign materials and merchandise. |

| Historical Exceptions | Early U.S. political cartoons sometimes used different colors, and the 19th century saw no consistent color scheme for parties. The current system is a relatively recent development. |

| Public Perception | The red-blue divide has become deeply ingrained in American political discourse, often symbolizing ideological and regional differences between states and voters. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical Origins: Early associations of colors with political ideologies in the 19th century

- Media Influence: TV color-coding in the 1976 U.S. presidential election solidified red/blue

- Psychological Factors: Red and blue evoke strong emotional responses, aiding party branding

- Geographic Shifts: Red/blue state labels emerged in 2000, reflecting regional political divides

- Global Variations: Other countries use different colors for their political party identities

Historical Origins: Early associations of colors with political ideologies in the 19th century

The 19th century laid the groundwork for the symbolic use of colors in politics, though not in the red-versus-blue dichotomy familiar to modern American audiences. Instead, this era saw colors like red, blue, and others take on ideological meanings across Europe and the United States, often tied to revolutionary movements, monarchies, and emerging class struggles. Red, for instance, became associated with socialism and communism after the 1848 revolutions, symbolizing the bloodshed of workers fighting for their rights. This association was cemented further by the Paris Commune of 1871, where red flags were prominently displayed as a sign of defiance against the bourgeoisie. Blue, on the other hand, was often linked to conservatism and monarchy, particularly in countries like France and Germany, where royal families used it as a symbol of authority and tradition.

To understand these early associations, consider the role of uniforms and flags in political movements. The French Revolution introduced the tricolor flag—blue, white, and red—which later influenced other nations. However, the individual colors took on distinct meanings: blue was adopted by conservatives as a nod to the pre-revolutionary order, while red became the banner of radicals and reformers. In the United States, the Whig Party (predecessor to the Republican Party) used blue and buff (a tan color) in the mid-19th century, though these colors were more about historical symbolism than ideological alignment. Meanwhile, in Britain, the Tories (later Conservatives) were associated with blue, while the Whigs (later Liberals) used orange or red, reflecting the European trend of blue representing tradition and red signifying reform.

A key takeaway from this period is how colors were used to communicate complex ideologies in a visually literate society. For example, the red flag of the labor movement wasn’t just a color choice—it was a deliberate symbol of sacrifice and solidarity. Similarly, blue’s association with conservatism wasn’t arbitrary; it drew on its historical use by monarchies and established institutions. These early associations were fluid and context-dependent, varying by country and movement. In Germany, for instance, black became the color of Catholicism and conservatism, while red remained tied to socialism. This diversity highlights how colors were tools of identity, not rigidly defined categories.

Practical tip: When analyzing historical color symbolism, always consider the cultural and political context. For instance, red’s association with socialism in Europe doesn’t directly translate to its use in the American context, where it later became linked to the Republican Party. Understanding these nuances can help avoid oversimplification and provide a richer interpretation of political symbolism.

In conclusion, the 19th century’s use of colors in politics was a precursor to modern associations, but it was far more varied and ideologically charged. Red and blue, among other colors, were deployed to represent revolutionary zeal, conservative tradition, and everything in between. By examining these early associations, we gain insight into how visual symbols can shape political identities and how their meanings evolve over time. This historical perspective is essential for anyone seeking to understand the origins of today’s color-coded political landscape.

Exploring Venezuela's Political Landscape: The Number of Active Parties

You may want to see also

Media Influence: TV color-coding in the 1976 U.S. presidential election solidified red/blue

The 1976 U.S. presidential election marked a pivotal moment in the color-coding of American political parties, largely due to the influence of television media. Prior to this election, party colors were not consistently assigned, and their usage was sporadic. However, the advent of color television and the need for visually engaging broadcasts led networks to adopt a standardized color scheme. NBC, a major player in election coverage, chose red for Republicans and blue for Democrats, a decision that would have lasting implications. This seemingly arbitrary choice was driven by practical considerations—red and blue offered high contrast and were easily distinguishable on screen. Little did the networks know they were inadvertently shaping a political lexicon that would endure for decades.

The analytical lens reveals that the 1976 election was a perfect storm of technological advancement and media innovation. Color television was becoming ubiquitous in American households, and networks sought to capitalize on this by creating visually compelling election coverage. The use of red and blue allowed viewers to quickly grasp the electoral map’s dynamics, enhancing the viewer experience. This practical decision, however, was not without consequence. By consistently pairing Republicans with red and Democrats with blue, the media inadvertently reinforced these associations in the public mind. What began as a broadcast design choice evolved into a cultural shorthand, solidifying the colors as party identifiers.

To understand the persuasive power of this color-coding, consider how repetition shapes perception. Each election cycle following 1976 reinforced the red-Republican and blue-Democrat association, embedding it deeper into the national consciousness. By the 2000 election, these colors were so ingrained that they became the standard for political maps, merchandise, and discourse. This demonstrates how media decisions, even those driven by logistical concerns, can have far-reaching cultural impacts. For instance, a viewer in 1976 might have simply noted the colors as a helpful visual aid, but by 2000, they were integral to how Americans understood political affiliation.

A comparative analysis highlights the contrast between the fluidity of party colors before 1976 and their rigidity afterward. In earlier elections, newspapers and broadcasters often used different colors or no colors at all, leading to confusion. The 1976 election’s standardized approach eliminated this inconsistency, creating a unified visual language. This uniformity not only improved media coverage but also streamlined public understanding of election results. For example, a family watching the returns in 1976 could easily follow the red and blue states, a simplicity that previous elections lacked. This clarity was a significant factor in the colors’ enduring adoption.

In conclusion, the 1976 U.S. presidential election serves as a case study in how media influence can shape political culture. The decision to use red for Republicans and blue for Democrats was initially a practical solution for television broadcasts, but it quickly transcended its original purpose. Through repeated exposure, these colors became inseparable from their respective parties, illustrating the unintended consequences of media innovation. Today, the red-blue divide is a cornerstone of American political identity, a testament to the power of visual communication in shaping public perception. For those studying political branding or media history, this example underscores the importance of considering how small design choices can lead to significant cultural shifts.

How to Start Your Own Political Party: A Step-by-Step Guide

You may want to see also

Psychological Factors: Red and blue evoke strong emotional responses, aiding party branding

The colors red and blue are not merely aesthetic choices in political branding; they are powerful psychological tools that tap into deep-seated emotional responses. Red, often associated with the Republican Party in the U.S., evokes feelings of urgency, passion, and strength. It is a color that demands attention, making it ideal for a party that emphasizes themes like national security and economic boldness. Blue, on the other hand, linked to the Democratic Party, conveys calmness, trust, and stability. This color resonates with a party that prioritizes social welfare, unity, and long-term progress. These emotional triggers are not accidental but are strategically employed to reinforce party identities and sway voter perceptions.

Consider the neurological impact of these colors. Studies in color psychology show that red can increase heart rate and create a sense of alertness, while blue has a calming effect, reducing stress and fostering a sense of security. Political parties leverage these physiological responses to align their messaging with voter emotions. For instance, a red campaign poster might heighten a voter’s sense of urgency about an issue, while a blue one could reassure them of a party’s reliability. This subtle manipulation of emotions is a cornerstone of effective political branding, turning colors into silent persuaders in the electoral arena.

Practical application of these colors extends beyond posters and logos. In televised debates, the backdrop, attire, and even lighting often incorporate red or blue to reinforce party messaging. For example, a Republican candidate might wear a red tie to project confidence and assertiveness, while a Democrat might opt for a blue suit to appear approachable and trustworthy. These choices are not arbitrary; they are calculated moves to activate the emotional associations voters have with these colors. Even digital campaigns use red and blue in buttons, banners, and graphics to drive engagement and reinforce party loyalty.

However, the effectiveness of red and blue branding is not universal. Cultural and historical contexts play a role in how these colors are perceived. In some countries, red symbolizes revolution or socialism, while blue may represent conservatism. Political parties must therefore adapt their color strategies to local nuances. For instance, in the U.K., red is traditionally associated with the Labour Party (left-leaning), while blue represents the Conservatives (right-leaning), a reversal of the U.S. pattern. Understanding these variations is crucial for global political branding, ensuring that colors align with the intended emotional response rather than creating unintended associations.

In conclusion, the psychological power of red and blue in political branding lies in their ability to evoke strong, immediate emotional responses. By tapping into these innate reactions, parties can strengthen their identities, influence voter perceptions, and create lasting connections with their audiences. Whether through visual campaigns, strategic attire, or digital design, the use of these colors is a masterclass in leveraging psychology for political advantage. As voters, recognizing this manipulation can help us critically evaluate the messages we receive, separating emotional appeal from substantive policy.

Understanding the Role of a Political Party's National Committee

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Geographic Shifts: Red/blue state labels emerged in 2000, reflecting regional political divides

The year 2000 marked a pivotal moment in American political discourse with the widespread adoption of "red state" and "blue state" labels, a color-coding system that visually mapped the country's deepening regional political divides. This shift was not merely a media invention but a reflection of emerging geographic trends in voting patterns. The 2000 presidential election, with its contentious recount in Florida, highlighted the stark contrast between states consistently voting Republican (red) and those favoring Democrats (blue). This visual representation on electoral maps quickly became a shorthand for understanding the nation’s political landscape, embedding itself into the public consciousness.

Analyzing the origins of this color scheme reveals a lack of historical precedent. Prior to 2000, media outlets used varying colors to represent parties, with no consistent standard. The red-blue designation gained traction during the prolonged election night coverage in 2000, as networks sought a clear, intuitive way to display results. The choice of red for Republicans and blue for Democrats was largely arbitrary, but its repetition across major networks solidified the convention. This accidental standardization transformed how Americans perceive political geography, turning abstract data into a vivid, easily digestible narrative.

The red-blue divide quickly transcended electoral maps, becoming a cultural shorthand for broader ideological differences. Red states, predominantly in the South and Midwest, were associated with conservative values, while blue states, concentrated on the coasts, symbolized liberal ideals. This geographic polarization was not just a media construct but mirrored real demographic and policy divides. For instance, red states often emphasized issues like gun rights and religious freedom, while blue states prioritized social services and environmental regulation. The labels, though oversimplified, captured a growing sense of regional identity and political alignment.

However, the red-blue framework is not without its limitations. It risks oversimplifying complex political realities, reducing entire states to a single color despite internal diversity. For example, urban centers in red states often lean blue, while rural areas in blue states may skew red. This binary system can also reinforce stereotypes, painting regions as monolithic blocs rather than dynamic, multifaceted communities. Critics argue that such labels contribute to political polarization by encouraging a "us vs. them" mentality, making compromise and dialogue more difficult.

Despite these critiques, the red-blue state labels remain a powerful tool for understanding geographic shifts in American politics. They provide a visual framework for tracking trends, such as the gradual shift of suburban areas from red to blue or the solidification of rural regions as Republican strongholds. For educators, journalists, and policymakers, this color-coding offers a starting point for deeper analysis, encouraging exploration of the economic, social, and cultural factors driving political alignment. As the nation continues to evolve, the red-blue map will likely adapt, reflecting new divides and coalitions in the ever-changing American political landscape.

Political Appointees as Ambassadors: Unveiling the Diplomatic Appointments

You may want to see also

Global Variations: Other countries use different colors for their political party identities

The association of political parties with specific colors is not a universal phenomenon, and the red-blue dichotomy familiar to American audiences is largely absent in other parts of the world. In many countries, political parties adopt colors based on historical, cultural, or ideological factors unique to their context. For instance, in the United Kingdom, the Conservative Party is traditionally associated with blue, while the Labour Party is linked to red. However, these colors do not align with the American red-blue divide, where Republicans are red and Democrats are blue. This divergence highlights the localized nature of color symbolism in politics.

Consider India, a nation with a vibrant multi-party system, where color plays a significant role in party identity. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) uses saffron, a color deeply rooted in Hindu culture and symbolizing purity and sacrifice. In contrast, the Indian National Congress (INC) adopts a more secular palette with colors like white and green, reflecting its historical ties to India’s independence movement. These choices are not arbitrary but are deeply embedded in the country’s cultural and historical fabric, illustrating how colors can convey complex ideological messages.

In Latin America, political color schemes often reflect regional identities and revolutionary histories. For example, in Mexico, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) is associated with green, white, and red—the colors of the Mexican flag—emphasizing its nationalist roots. Meanwhile, in Venezuela, the United Socialist Party (PSUV) uses red to signify its socialist and revolutionary ideals, a stark contrast to the blue often used by opposition parties. These examples demonstrate how colors can serve as powerful tools for political branding, resonating with local audiences in ways that transcend mere aesthetics.

A comparative analysis reveals that while some countries adopt colors based on historical or cultural significance, others use them strategically to differentiate themselves from opponents. In Germany, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) is associated with black, a color chosen for its neutrality and professionalism, while the Social Democratic Party (SPD) uses red to align with its socialist roots. In contrast, Brazil’s Workers’ Party (PT) employs a combination of red and white, symbolizing both its leftist ideology and a commitment to transparency. These variations underscore the importance of understanding local contexts when interpreting political color symbolism.

For those interested in political branding or cross-cultural communication, a practical tip is to research the historical and cultural underpinnings of a country’s political color schemes before making assumptions. Misinterpreting these symbols can lead to misunderstandings or unintended offense. For instance, using red in a campaign in China might evoke associations with the Communist Party, while in South Africa, the color green is strongly linked to the African National Congress (ANC). By approaching these color identities with cultural sensitivity, individuals can navigate global political landscapes more effectively.

Independent Path to Power: Running for President Without a Party

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The association of the Democratic Party with blue began in the 2000 U.S. presidential election, when news networks used blue to represent states won by Al Gore. Prior to this, there was no consistent color scheme, but the media's standardization during this election solidified blue as the Democratic color.

Similar to the Democrats, the Republican Party's association with red also stems from the 2000 election. News networks used red to represent states won by George W. Bush, and this color coding became the standard for identifying Republican victories in subsequent elections.

No, the red-blue color scheme is relatively recent. Before 2000, there was no consistent color designation for U.S. political parties. The media's decision to standardize colors during the 2000 election led to the widespread adoption of red for Republicans and blue for Democrats.

No, the use of red and blue for political parties varies by country. For example, in the UK, red is associated with the Labour Party, while blue represents the Conservative Party. The U.S. red-blue scheme is specific to American politics and its media conventions.