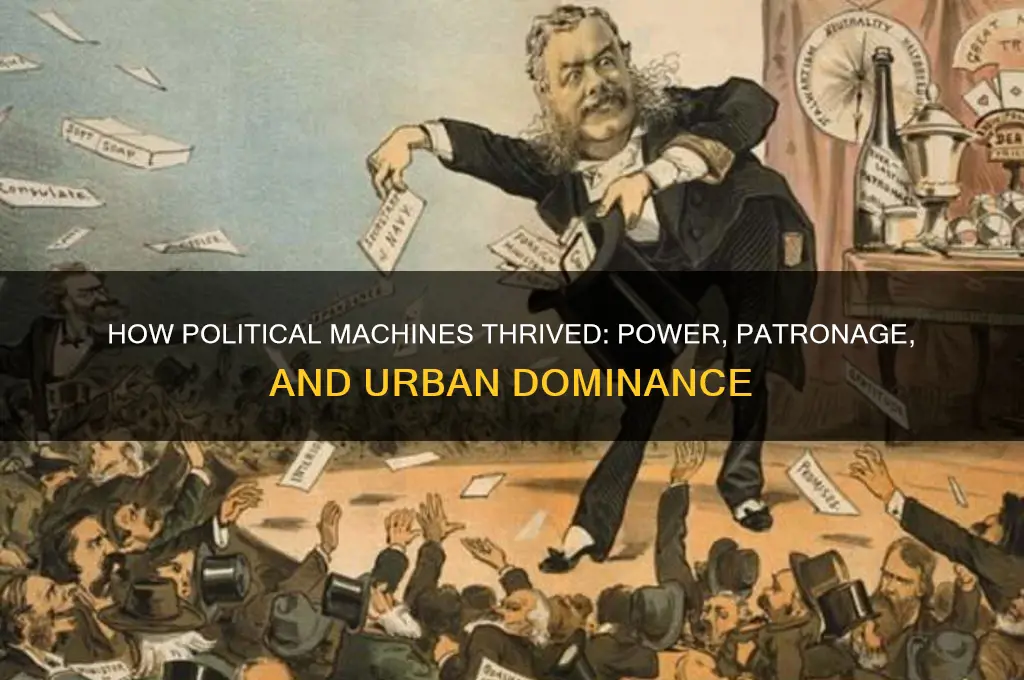

Political machines thrived by leveraging a combination of patronage, local control, and strategic alliances to dominate urban political landscapes, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. These organizations, often tied to major political parties, exchanged favors, jobs, and services for votes, creating a system of mutual dependency between machine bosses and constituents. By controlling key institutions like police departments, courts, and public works, machines ensured their influence permeated every level of local governance. They capitalized on the needs of immigrant communities, providing essential services and social support in exchange for political loyalty, while also exploiting corruption and coercion to maintain power. This symbiotic relationship allowed machines to dominate elections, shape policies, and consolidate their hold on cities, despite widespread criticism of their undemocratic practices.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Patronage and Spoils System | Distribution of government jobs and contracts to loyal supporters. |

| Strong Local Control | Dominance over city or state politics through grassroots networks. |

| Clientelism | Exchange of favors (e.g., jobs, services) for political support. |

| Voter Mobilization | Organized efforts to register and turn out voters, often using coercion. |

| Corruption and Graft | Misuse of public funds and resources for personal or political gain. |

| Ethnic and Immigrant Support | Catering to the needs of immigrants and ethnic groups for political loyalty. |

| Lack of Transparency | Opaque decision-making processes to maintain control. |

| Monopoly on Local Services | Control over essential services like sanitation, housing, and employment. |

| Political Bosses | Powerful leaders who controlled the machine and made key decisions. |

| Weak Legal Enforcement | Exploitation of loopholes or lack of enforcement to operate with impunity. |

| Media Influence | Ownership or control of local media to shape public opinion. |

| Electoral Fraud | Manipulation of elections through ballot stuffing, voter intimidation, etc. |

| Community Engagement | Providing social services to gain loyalty and support from communities. |

| Hierarchical Structure | Organized tiers of power from local ward bosses to the machine leader. |

| Adaptation to Change | Evolving strategies to maintain relevance in shifting political landscapes. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Boss-led patronage systems rewarded loyalists with jobs, contracts, and favors for political support

- Immigrant communities relied on machines for services, jobs, and assimilation into urban life

- Machines controlled elections through voter fraud, intimidation, and manipulation of polling places

- Weak governance and corruption allowed machines to dominate local and state politics unchecked

- Machines provided social welfare, filling gaps left by inadequate government assistance programs

Boss-led patronage systems rewarded loyalists with jobs, contracts, and favors for political support

Political machines thrived by leveraging a simple yet powerful mechanism: boss-led patronage systems. At their core, these systems operated on a transactional basis, exchanging jobs, contracts, and favors for unwavering political support. This quid pro quo dynamic created a network of loyalists who were deeply invested in the machine’s success, ensuring its dominance in local and sometimes national politics. The boss, often a charismatic and influential figure, acted as the central hub, distributing rewards and maintaining control through a hierarchy of operatives.

Consider the Tammany Hall machine in 19th-century New York City, a quintessential example of this system. Bosses like William Tweed allocated government jobs to immigrants in exchange for votes, effectively securing their political base. For instance, a newly arrived Irish immigrant might be offered a position as a street cleaner or a clerk in a government office. In return, they were expected to mobilize their community during elections, ensuring the machine’s candidates won. This reciprocal relationship not only solidified the machine’s power but also provided tangible benefits to marginalized groups, fostering a sense of loyalty and dependence.

The effectiveness of these systems lay in their ability to address immediate needs while building long-term political capital. Jobs and contracts were not just rewards; they were lifelines in economically precarious times. For example, during the Great Depression, political machines in cities like Chicago and Philadelphia distributed relief jobs to thousands, cementing their popularity. However, this approach was not without risks. Critics argued that it fostered corruption, as contracts were often awarded to loyalists rather than the most qualified bidders, and jobs became tools for coercion rather than public service.

To implement such a system effectively, a boss needed to balance generosity with discipline. Over-rewarding could deplete resources, while stinginess could erode loyalty. A practical tip for maintaining control was to create a tiered system of rewards, where lower-level operatives received smaller favors (e.g., minor jobs or permits) and higher-level loyalists gained access to lucrative contracts. Additionally, bosses often used informal networks to monitor compliance, ensuring that supporters remained active and obedient. This structured yet flexible approach allowed machines to adapt to changing political landscapes while retaining their core advantage.

In conclusion, boss-led patronage systems were a double-edged sword. While they provided a means for political machines to thrive by securing loyal support, they also perpetuated practices that undermined transparency and fairness. Understanding this dynamic offers insights into the complexities of power and governance, highlighting the delicate balance between rewarding loyalty and maintaining public trust. For those studying political history or seeking to understand modern political networks, examining these systems reveals enduring lessons about the interplay between personal interests and collective goals.

Is Politico Truly Unbiased? Analyzing Its Editorial Stance and Reporting

You may want to see also

Immigrant communities relied on machines for services, jobs, and assimilation into urban life

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, immigrant communities in American cities often found themselves in a precarious position, navigating unfamiliar urban landscapes with limited resources and social networks. Political machines stepped into this void, offering essential services, employment opportunities, and a pathway to assimilation. These machines, led by powerful bosses like Tammany Hall’s William Tweed, understood that immigrants were a vital constituency. By providing tangible benefits—such as jobs on public works projects, legal assistance, and even coal for winter—machines secured loyalty and votes. This transactional relationship was not merely exploitative; for many immigrants, it was a lifeline in a hostile environment.

Consider the Irish immigrants in New York City, who arrived en masse during the Great Famine. Tammany Hall recognized their potential as a voting bloc and actively courted them by sponsoring St. Patrick’s Day parades, offering jobs as policemen or firefighters, and helping them navigate the complexities of American citizenship. In return, the Irish became staunch supporters of the Democratic Party, which Tammany controlled. This pattern repeated across ethnic groups: Italian, Polish, and Jewish immigrants also relied on machines for similar support, creating a symbiotic relationship that bolstered the machines’ power.

However, this reliance was not without its pitfalls. Machines often demanded absolute loyalty, using patronage to control political outcomes. For instance, immigrants might be required to vote a specific ticket or risk losing their jobs. This system, while effective, perpetuated corruption and undermined democratic principles. Yet, for many immigrants, the immediate benefits outweighed the long-term costs. The machines provided a sense of belonging and security, helping them integrate into urban life at a time when mainstream society often excluded them.

To understand this dynamic, imagine arriving in a foreign city with no job, limited language skills, and no social connections. A political machine offers you a job, helps you find housing, and even assists with naturalization paperwork. In exchange, you’re asked to vote for their candidates. For most, this is a practical choice, not a moral compromise. The machines’ ability to meet these basic needs made them indispensable to immigrant communities, ensuring their dominance in urban politics for decades.

In practical terms, immigrants could approach machine-affiliated ward heelers—local representatives of the political machine—for assistance. These heelers acted as intermediaries, connecting immigrants to resources and opportunities. For example, a newly arrived Italian family might receive help enrolling their children in school or securing a vendor’s license for a street cart. Over time, these small acts of assistance fostered deep-rooted loyalty, turning immigrants into reliable supporters of the machine’s agenda. This grassroots approach was key to the machines’ success, as it created a network of dependency that sustained their power.

Ultimately, the reliance of immigrant communities on political machines highlights a critical aspect of urban history: the intersection of survival, politics, and identity. While the machines’ methods were often questionable, their role in facilitating immigrant assimilation cannot be overlooked. They provided a bridge between the old world and the new, offering practical solutions to immediate problems. For immigrants, this was not just about politics—it was about survival, belonging, and building a future in an unfamiliar land.

Dollar Shave Club's Political Stance: Unpacking Brand Values and Controversies

You may want to see also

Machines controlled elections through voter fraud, intimidation, and manipulation of polling places

Political machines thrived by mastering the art of controlling elections, often through voter fraud, intimidation, and manipulation of polling places. These tactics were not merely incidental but central to their dominance, ensuring that their candidates won regardless of the true will of the electorate. By systematically undermining the integrity of the electoral process, machines turned democracy into a tool for their own advancement.

Consider the mechanics of voter fraud, a cornerstone of machine strategy. One common method was "repeater voting," where individuals voted multiple times under different names. Machines maintained detailed lists of deceased voters, recent immigrants, or fictitious identities, ensuring these names appeared on voter rolls. For instance, in late 19th-century New York, Tammany Hall operatives would shuttle repeat voters from one polling place to another, providing them with pre-marked ballots or coaching them on how to vote. This required meticulous organization: operatives had to coordinate transportation, provide false identification, and ensure poll workers looked the other way. The takeaway? Fraud wasn’t random—it was a science, requiring resources, planning, and a network of complicit individuals.

Intimidation was another weapon in the machine arsenal, particularly effective in immigrant or marginalized communities. Operatives would station themselves at polling places, using physical presence, threats, or bribes to sway votes. For example, in Chicago during the early 20th century, machine bosses like those in the Democratic Party would send "sluggers" to polling sites. These enforcers might block access to voters who opposed their candidates or openly confront them, creating an atmosphere of fear. Practical tip: Machines often targeted vulnerable groups, such as recent immigrants who were less familiar with voting laws or dependent on machine-controlled jobs. By controlling access to employment, housing, or even basic services, machines ensured compliance through coercion rather than persuasion.

Manipulation of polling places completed the trifecta. Machines often controlled the appointment of poll workers, allowing them to install loyalists who would turn a blind eye to irregularities or actively assist in fraud. Ballot boxes could be "stuffed" with fake votes, or legitimate ballots could be "lost" or tampered with. In some cases, polling places were relocated to machine-controlled territories at the last minute, confusing voters and reducing turnout among opponents. Comparative analysis: This strategy mirrored the tactics of authoritarian regimes, where control of electoral infrastructure is key to maintaining power. The difference? Machines operated within ostensibly democratic systems, exploiting loopholes and weaknesses to subvert the process from within.

The cumulative effect of these tactics was profound. By controlling elections through fraud, intimidation, and manipulation, machines ensured their candidates won consistently, consolidating power and resources. This allowed them to deliver favors to their constituents, perpetuating a cycle of dependency and loyalty. However, the cost was immense: the erosion of public trust in democracy and the entrenchment of corruption. For those studying political history or seeking to combat modern electoral abuses, the lesson is clear: safeguarding polling places, enforcing voter identification laws, and ensuring transparency in electoral administration are critical steps to prevent such manipulation. Without these measures, even the most robust democracies remain vulnerable to those who would exploit them.

Mastering the Art of Polite Socializing: Tips for Hanging Out Gracefully

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Weak governance and corruption allowed machines to dominate local and state politics unchecked

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, weak governance structures in many American cities and states created fertile ground for political machines to flourish. These machines, often led by charismatic bosses, exploited the lack of oversight and accountability in local governments. For instance, Tammany Hall in New York City thrived by filling the void left by ineffective public institutions, offering services like jobs, housing, and even food in exchange for political loyalty. This symbiotic relationship between needy citizens and opportunistic machine leaders was made possible by the absence of robust checks and balances, allowing machines to operate with impunity.

Corruption was the lifeblood of these political machines, enabling them to dominate local and state politics unchecked. By bribing officials, rigging elections, and controlling patronage systems, machine bosses ensured their grip on power. Take Chicago’s Democratic machine under Mayor Richard J. Daley, which used voter fraud and intimidation to maintain control. Similarly, in cities like Philadelphia and Kansas City, machines manipulated election boards and police departments to suppress opposition. Weak governance not only failed to curb these practices but often became complicit, as corrupt officials were either bought off or intimidated into compliance.

The interplay between weak governance and corruption created a self-perpetuating cycle that sustained political machines. Without strong legal frameworks or independent judiciary systems, machines faced little resistance in bending rules to their advantage. For example, in Rhode Island, the machine led by Providence Mayor Buddy Cianci thrived by exploiting lax campaign finance laws and weak ethics regulations. This environment allowed machines to funnel public resources into private pockets, further entrenching their power. Citizens, often dependent on machine-provided services, had little recourse to challenge the status quo.

To dismantle the dominance of political machines, practical steps must be taken to strengthen governance and combat corruption. Implementing stricter campaign finance laws, establishing independent oversight bodies, and increasing transparency in public spending are essential. For instance, cities like New York have introduced reforms such as nonpartisan election boards and stricter lobbying regulations to curb machine influence. Additionally, empowering citizens through education and civic engagement can break the cycle of dependency on machines. By addressing the root causes of weak governance and corruption, communities can reclaim their political systems from machine control.

Is Congressional Oversight Political? Examining Partisanship in Government Watchdog Roles

You may want to see also

Machines provided social welfare, filling gaps left by inadequate government assistance programs

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, political machines thrived by embedding themselves into the fabric of urban communities, often through the provision of social welfare services that government programs failed to deliver. These machines, led by bosses like Tammany Hall’s William M. Tweed in New York, recognized a critical gap: impoverished immigrants and working-class families lacked access to basic necessities like food, housing, and healthcare. By stepping in to provide these services—often in exchange for political loyalty—machines created a symbiotic relationship with their constituents. For instance, Tammany Hall distributed coal to heat homes during winter and organized soup kitchens during economic downturns. This practical support fostered dependency and gratitude, ensuring voters remained loyal to the machine’s candidates.

Consider the mechanics of this system: political machines operated as informal welfare states, leveraging their resources to address immediate needs. In Chicago, the Democratic machine under Anton Cermak provided jobs to the unemployed during the Great Depression, often through public works projects or patronage positions. Similarly, in Boston, the machine led by James Michael Curley funded programs like milk distribution for children and emergency housing for the homeless. These initiatives were not acts of altruism but strategic investments. By filling the void left by inadequate government assistance, machines secured votes and built a base of loyal supporters who viewed them as their primary source of aid.

However, this approach was not without its pitfalls. The welfare provided by machines was often inconsistent and contingent on political allegiance, creating a system of favoritism rather than universal support. For example, in Philadelphia, the Republican machine under Boies Penrose distributed relief only to those who could prove their loyalty through voting records or party membership. This conditional aid perpetuated inequality, as those outside the machine’s network were left to fend for themselves. Despite these flaws, the system worked because it addressed urgent needs that government programs ignored, making it a powerful tool for maintaining political control.

To replicate this strategy in a modern context—though ethically questionable—one might identify underserved communities and provide targeted assistance where government programs fall short. For instance, organizing food drives, offering free healthcare clinics, or providing job training programs could create a similar dependency. However, the key difference today would be the need for transparency and accountability, ensuring aid is distributed equitably rather than as a tool for manipulation. The takeaway is clear: political machines thrived by understanding and exploiting the gaps in social welfare, turning necessity into a source of power. Their success underscores the enduring importance of addressing basic human needs, even if their methods remain controversial.

Empowering Citizens: Strategies to Foster Political Awareness and Engagement

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Political machines thrived in urban areas by providing essential services and jobs to immigrants and the working class in exchange for political loyalty and votes. They filled the void left by weak or absent local governments, offering patronage, protection, and community support, which solidified their control over urban politics.

Immigration played a crucial role as newly arrived immigrants often lacked resources, language skills, and knowledge of local politics. Political machines exploited this vulnerability by offering assistance, such as jobs, housing, and legal aid, in exchange for votes and support, creating a dependent voter base.

Political machines maintained power by controlling key institutions like the police, courts, and local government, which allowed them to suppress opposition and manipulate elections. They also cultivated a strong grassroots network of precinct captains and ward bosses who ensured voter turnout and loyalty, making them difficult to dislodge.