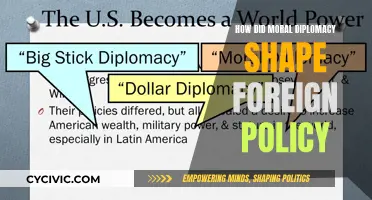

Between 1909 and 1913, President William Howard Taft and Secretary of State Philander C. Knox pursued a foreign policy known as dollar diplomacy. This policy, which was a continuation of Roosevelt's big stick diplomacy, aimed to exert American influence primarily through financial institutions and economic power, with the support of diplomats and the military. Dollar diplomacy, which was heavily criticised, had a significant impact on American culture, as it was one of the first times that the country actively pursued its economic interests on a global scale, setting a precedent for future foreign policy decisions.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Time Period | 1909-1913 |

| Key Figures | President William Howard Taft, Secretary of State Philander C. Knox, Theodore Roosevelt, Thomas A. Bailey, Woodrow Wilson |

| Definition | A foreign policy characterized by the use of economic power and private capital to exert American influence and further its aims, particularly in Latin America and East Asia |

| Goal | To create stability and promote American commercial interests, increase trade, and encourage and protect trade within Latin America and Asia |

| Methods | Use of American banks and financial interests, diplomats, arbitration, and the threat of economic pressure or military force |

| Regions of Focus | Central America, Venezuela, Cuba, the Caribbean, China, Japan, Manchuria |

| Outcomes | Increased American financial gain, hindered financial gain of other countries, economic instability, nationalist movements, heightened tensions with Japan, failure to maintain balance of power |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Dollar diplomacy was a foreign policy tool used by President William Howard Taft

- It was an attempt to promote American business interests abroad

- It was characterised by the use of economic power instead of military force

- It was successful in Latin America but failed in East Asia

- It was abandoned in 1912 and publicly repudiated by Woodrow Wilson in 1913

Dollar diplomacy was a foreign policy tool used by President William Howard Taft

Taft and his Secretary of State, Philander C. Knox, a corporate lawyer and founder of U.S. Steel, believed that diplomacy should create stability and order abroad, which would, in turn, promote American financial opportunities. This belief led to extensive U.S. interventions in Latin America and East Asia, particularly in Central America and the Caribbean, where they felt American investors would have a stabilizing effect on shaky governments.

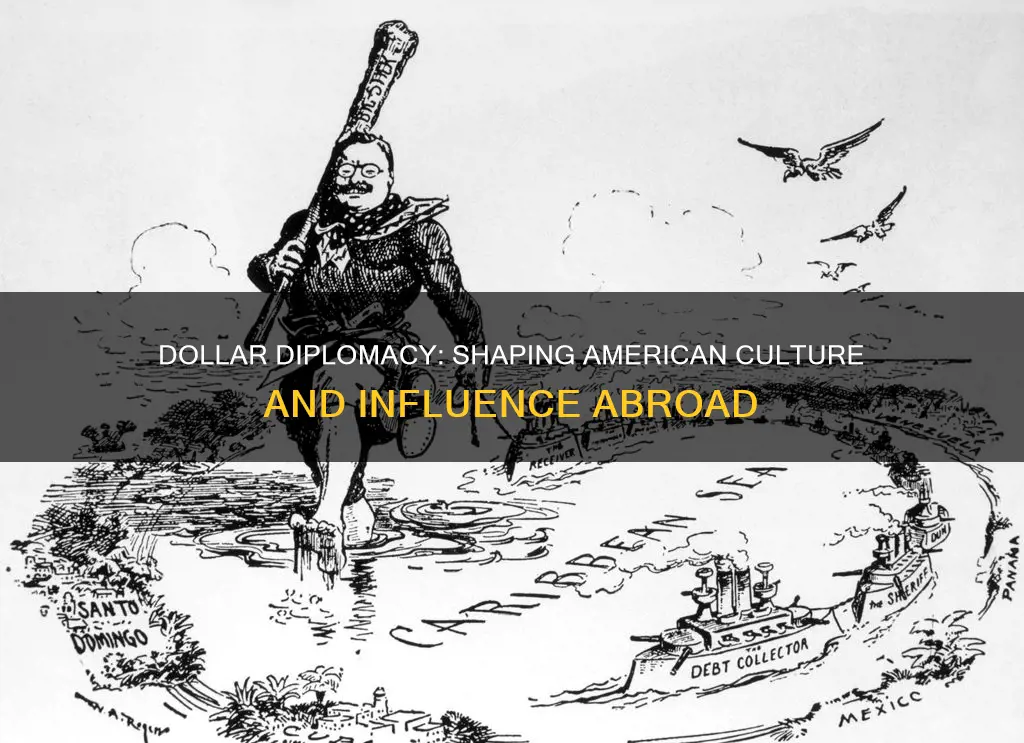

In Central America, Taft focused on countries with steep debts to European nations, such as Nicaragua, where he supported the overthrow of José Santos Zelaya and set up Adolfo Díaz in his place. He also used military force to pressure countries into accepting American loans to pay off their debts, which created years of economic instability and fostered nationalist movements driven by resentment of American interference.

In East Asia, dollar diplomacy aimed to use American banking power to create tangible American interests in China, limiting the scope of other powers and increasing opportunities for American trade and investment. While initially successful in developing the railroad industry in China, efforts to expand the Open Door policy into Manchuria met resistance from Russia and Japan, exposing the limits of American influence and the complexities of diplomacy.

Dollar diplomacy ultimately failed to achieve its goals and was abandoned by the Taft administration in 1912. It has since been criticized as a simplistic and formulaic manipulation of foreign affairs for strictly monetary gains, creating difficulties for the United States during and after Taft's presidency.

Political Campaigns: Vidant Employees' Involvement Boundaries

You may want to see also

It was an attempt to promote American business interests abroad

Dollar diplomacy was a foreign policy strategy employed by President William Howard Taft and Secretary of State Philander C. Knox from 1909 to 1913. It was characterized by the use of economic power and financial interests to promote American business interests abroad, particularly in Latin America and East Asia.

Taft and Knox believed that diplomacy should create stability and order abroad, which would, in turn, promote American commercial interests. They aimed to use private capital and the influence of American banks to further these interests, as evidenced by extensive interventions in Venezuela, Cuba, and Central America. This approach was defended as an extension of the Monroe Doctrine, with Taft preferring arbitration and economic coercion over military force to achieve foreign policy objectives.

In Central America, dollar diplomacy focused on addressing the steep debts that several countries owed to European nations. Taft moved quickly to pay off these debts with U.S. dollars, which made these countries indebted to the United States. This strategy, however, did little to relieve the debt burden and fostered nationalist movements driven by resentment of American interference.

In East Asia, dollar diplomacy aimed to establish tangible American interests in China, limit the influence of other powers, and increase trade and investment opportunities. This included securing the entry of American banking conglomerates, such as J.P. Morgan, into financing infrastructure projects like the construction of railways. While initially successful in developing the railroad industry in China, efforts to expand the Open Door policy deeper into Manchuria met with resistance from Russia and Japan, exposing the limitations of American influence.

Overall, dollar diplomacy sought to encourage and protect American trade and investment, particularly in Latin America and Asia. However, it faced criticism for its simplistic assessment of social unrest, formulaic application, and disregard for the complexities of international relations.

Social Media and Political Campaigns: Website Strategies

You may want to see also

It was characterised by the use of economic power instead of military force

Dollar diplomacy, a foreign policy strategy employed by President William Howard Taft from 1909 to 1913, was characterised by the use of economic power instead of military force to exert American influence and promote American commercial interests abroad. This approach, also known as "substituting dollars for bullets", aimed to increase American trade and investment in foreign markets, particularly in Latin America and East Asia.

Taft, along with Secretary of State Philander C. Knox, a corporate lawyer and founder of U.S. Steel, believed that diplomacy should create stability and order in other countries, which would, in turn, promote American financial opportunities. They sought to use private capital and the power of American banks to further U.S. interests overseas, especially in regions where American businesses had a strong presence, such as the Caribbean and Central America.

In Central America, for example, several countries owed significant debts to European nations. Taft intervened by paying off these debts with U.S. dollars, effectively shifting the indebtedness from European countries to the United States. While this strategy created economic instability and fostered nationalist movements driven by resentment towards American interference, it also gave the United States leverage over these countries. In one instance, when Nicaragua refused to accept American loans to repay its debt to Great Britain, Taft responded by sending a warship with marines to pressure the Nicaraguan government to agree to the loans.

Dollar diplomacy was also employed in East Asia, particularly in China. Knox secured the involvement of an American banking conglomerate headed by J.P. Morgan in the construction of a railway from Huguang to Canton (also known as the Guangzhou-Hankou railway). This intervention in China's railroad industry was intended to create tangible American interests in the region and limit the influence of other powers, such as Japan and Russia. However, these efforts heightened tensions between the United States and Japan, contributing to the outbreak of World War II.

Overall, dollar diplomacy reflected the belief that economic power could be a more effective tool than military force in achieving foreign policy objectives and promoting American commercial interests abroad. While it had some successes, it ultimately failed to achieve its goals and was abandoned by the Taft administration in 1912.

Union Dues: Political Campaign Spending Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

It was successful in Latin America but failed in East Asia

Dollar diplomacy was a foreign policy approach employed by the United States, particularly during the presidency of William Howard Taft from 1909 to 1913. It was characterised by the phrase "substituting dollars for bullets", reflecting the strategy of minimising military force and instead using America's economic power to guarantee loans to foreign countries. This policy was aimed at promoting stability and order abroad, ultimately to advance American commercial interests and increase trade.

Dollar diplomacy was successful in Latin America, where it was evident in extensive US interventions in the Caribbean and Central America. In Nicaragua, for example, the US supported the overthrow of José Santos Zelaya and installed Adolfo Díaz in his place, establishing a collector of customs and guaranteeing loans to the country. This was justified as a means to protect the Panama Canal. Similarly, in Honduras, Taft attempted to establish control by buying up the country's debt to British bankers. These interventions were driven by the belief that investors would stabilise the region's shaky governments.

However, dollar diplomacy failed in East Asia, specifically in China, due to several factors. Firstly, the American financial system was not equipped to handle international finance, such as large loans and investments, and had to rely primarily on London. This dependence on British financial support limited America's ability to manoeuvre independently. Additionally, other powers, such as Japan and Russia, had established interests in the region, and dollar diplomacy alienated them, creating suspicion and hostility towards American motives.

Furthermore, the assumption that American financial interests could easily mobilise their power in East Asia proved false. The US faced resistance from other countries with territorial interests in China, such as naval bases and designated geographical areas. The entry of an American banking conglomerate, headed by J.P. Morgan, into the construction of a railway from Huguang to Canton sparked a "Railway Protection Movement" revolt against foreign investment that overthrew the Chinese government. This revolt highlighted the limitations of America's global influence and understanding of international diplomacy.

In conclusion, while dollar diplomacy achieved some successes in Latin America through interventions that promoted American commercial interests, it ultimately failed in East Asia due to a combination of financial limitations, competition from other powers, and a misunderstanding of the region's dynamics.

Newspapers' Ethical Dilemma: Political Lies

You may want to see also

It was abandoned in 1912 and publicly repudiated by Woodrow Wilson in 1913

Dollar diplomacy, a foreign policy approach characterized by the use of American economic power to exert influence abroad, was pursued by President William Howard Taft and Secretary of State Philander C. Knox from 1909 to 1912. This policy, often described as "substituting dollars for bullets," aimed to promote American commercial interests and financial opportunities overseas, particularly in Latin America and East Asia.

However, dollar diplomacy faced significant challenges and criticism during its implementation. It failed to effectively address social unrest and economic instability in various countries, including Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and China. The policy's simplistic and formulaic approach led to its eventual abandonment by the Taft administration in 1912.

In his message to Congress on December 3, 1912, Taft acknowledged the limitations of dollar diplomacy and characterized his program as responding to "modern ideas of commercial intercourse." He expressed a desire to appeal to humanitarian sentiments and legitimate commercial aims while promoting stability and American trade globally.

Despite abandoning dollar diplomacy, Taft maintained his activist approach to foreign policy. He continued to pursue arbitration as a preferred method of settling international disputes and sought to increase American influence on the world stage.

When Woodrow Wilson became president in March 1913, he immediately and publicly repudiated dollar diplomacy. Wilson's rejection of this policy signaled a shift away from the manipulation of foreign affairs solely for monetary gains. However, it is important to note that Wilson still actively worked to maintain American supremacy in regions like Central America and the Caribbean.

Political Campaign T-Shirts: Effective Advertising Strategy?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Dollar Diplomacy was a foreign policy approach used by President William Howard Taft and Secretary of State Philander C. Knox from 1909 to 1913. It was characterised by the use of America's economic power, rather than military force, to exert influence and achieve foreign policy goals.

Dollar Diplomacy was driven by the belief that the role of diplomacy was to create stability abroad and, in doing so, promote American commercial interests. This policy influenced American culture by encouraging and protecting trade within Latin America and Asia, particularly in the Caribbean. It also led to extensive U.S. interventions in Venezuela, Cuba, and Central America, which were undertaken to safeguard American financial interests in these regions.

Dollar Diplomacy was ultimately unsuccessful. While it was intended to promote stability and improve financial opportunities, it failed to achieve these goals in the long term. In Central America, for example, the policy reassigned debt from European countries to the United States, creating years of economic instability and fostering nationalist movements driven by resentment of American interference. In Asia, Dollar Diplomacy sowed the seeds of mistrust and heightened tensions between the United States and Japan, which would eventually explode with the outbreak of World War II.