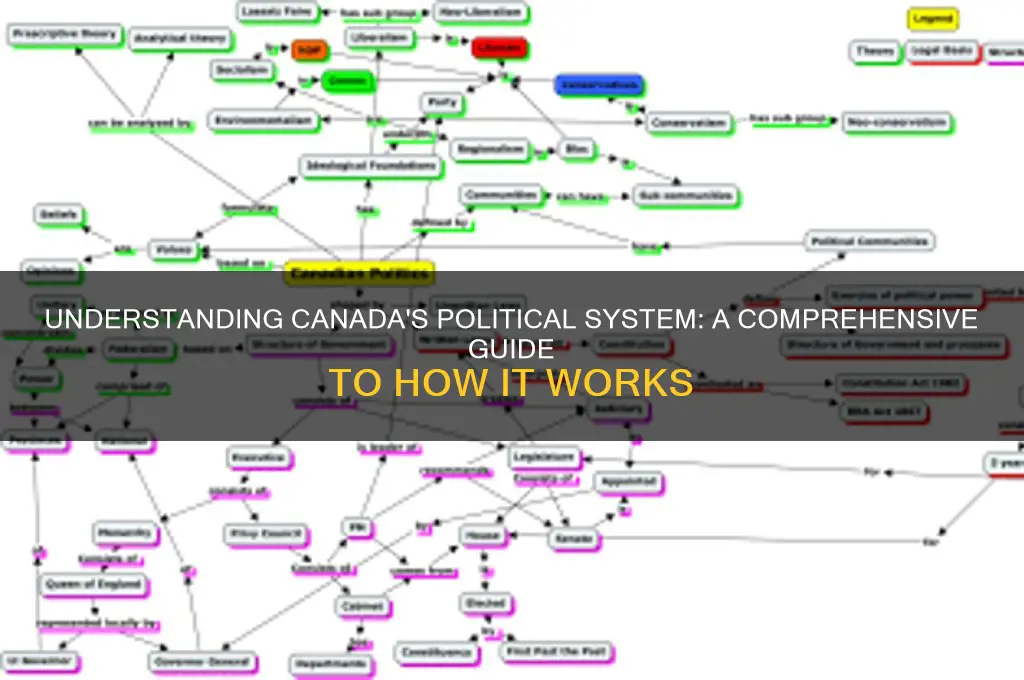

Canadian politics operate within a parliamentary democracy and constitutional monarchy, where the country’s governance is structured around the federal system, dividing powers between the national government and ten provinces. The political landscape is dominated by a multi-party system, with the Liberal Party, Conservative Party, New Democratic Party, and Bloc Québécois being the most prominent. The Prime Minister, typically the leader of the party with the most seats in the House of Commons, holds significant executive power, while the ceremonial role of the monarch is represented by the Governor General. Legislation is created through collaboration between the elected House of Commons and the appointed Senate, with the Charter of Rights and Freedoms ensuring fundamental freedoms and legal protections. Elections are held at least every four years, and Canada’s political culture emphasizes compromise, consensus, and a strong commitment to social welfare programs, reflecting its diverse and inclusive society.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Parliamentary System: Canada’s federal structure, roles of PM, MPs, and Senate in governance

- Electoral Process: First-past-the-post voting, ridings, and election campaigns in Canada

- Federal-Provincial Relations: Power division, provincial autonomy, and intergovernmental cooperation

- Political Parties: Major parties (Liberal, Conservative, NDP), ideologies, and party dynamics

- Judicial System: Role of courts, Supreme Court, and constitutional interpretation in politics

Parliamentary System: Canada’s federal structure, roles of PM, MPs, and Senate in governance

Canada’s federal structure operates as a parliamentary democracy, blending British traditions with unique Canadian adaptations. At its core is a division of powers between the federal government and ten provinces, outlined in the Constitution Act, 1867. The federal government handles national concerns like defense, foreign affairs, and currency, while provinces manage areas such as education, healthcare, and natural resources. This dual framework ensures regional autonomy while maintaining national cohesion, a critical balance in a geographically vast and culturally diverse country.

The Prime Minister (PM) is the central figure in Canada’s governance, wielding significant power despite not being directly elected by the public. The PM is typically the leader of the party holding the most seats in the House of Commons and serves as the head of government, chairing the Cabinet and setting the national agenda. Their role is both executive and legislative, as they must maintain the confidence of the House to remain in power. This system prioritizes party discipline, as the PM relies on their caucus to pass legislation and avoid non-confidence votes.

Members of Parliament (MPs) are elected representatives who form the House of Commons, the lower chamber of Canada’s bicameral legislature. Their primary roles include debating and voting on legislation, holding the government accountable through questions and committees, and representing their constituents’ interests. Unlike in presidential systems, Canadian MPs are bound by party loyalty, often voting along party lines rather than individual conscience. However, backbench MPs (those not in Cabinet) can still influence policy through committee work or by advocating for local issues, though their power is constrained by the PM’s authority.

The Senate, often called the “Chamber of Sober Second Thought,” complements the House of Commons as the upper chamber. Senators are appointed by the Governor General on the advice of the PM, typically to serve until age 75. While the Senate reviews and amends legislation, its role is largely advisory, as the House of Commons holds ultimate legislative authority. Critics argue the Senate lacks democratic legitimacy due to its unelected nature, but proponents highlight its regional representation and ability to provide non-partisan scrutiny. Recent reforms aim to make the Senate more independent, though its fundamental structure remains unchanged.

In practice, Canada’s parliamentary system emphasizes accountability and flexibility. The PM’s power is checked by the need to maintain parliamentary confidence, while MPs and Senators play distinct but interconnected roles in governance. This structure fosters both stability and responsiveness, allowing for swift decision-making while ensuring regional and minority voices are heard. However, it also relies heavily on party discipline, which can limit individual MPs’ autonomy and amplify the PM’s influence. Understanding these dynamics is key to navigating Canada’s political landscape.

Hoodwinked: Unveiling Political Allegory in the Classic Fairy Tale

You may want to see also

Electoral Process: First-past-the-post voting, ridings, and election campaigns in Canada

Canada’s federal electoral process hinges on the first-past-the-post (FPTP) system, a winner-takes-all mechanism where the candidate with the most votes in a riding wins, regardless of whether they achieve a majority. This system, inherited from the UK, prioritizes simplicity and decisiveness but often produces outcomes where the winning party’s seat count far exceeds its popular vote share. For instance, in the 2019 federal election, the Conservatives won 34.3% of the popular vote but only secured 121 of 338 seats, while the Liberals formed a minority government with 157 seats despite earning just 33.1% of the vote. This disparity underscores FPTP’s tendency to amplify regional support and penalize parties with geographically dispersed voters, like the NDP or Bloc Québécois.

Ridings, or electoral districts, are the building blocks of this system, each represented by a single Member of Parliament (MP). Canada’s 338 ridings are redrawn every decade by independent commissions to reflect population shifts, ensuring roughly equal representation. However, this process isn’t without controversy. Urban ridings often have significantly larger populations than rural ones, raising questions about voter equality. For example, the riding of Toronto Centre has over 120,000 residents, while Nunavut, a vast but sparsely populated territory, constitutes a single riding with just 37,000 people. This imbalance highlights the challenge of balancing geographic representation with demographic fairness in a country as geographically diverse as Canada.

Election campaigns in Canada are intense, tightly regulated, and relatively short, typically lasting 36 to 38 days. Parties must navigate strict spending limits, which vary by riding and are adjusted for inflation. In 2021, the maximum expenditure per candidate was $109,776 in the first 36 days, plus an additional $0.85 per voter for each additional day. Campaigns are also subject to blackout rules prohibiting the broadcast of election-related content outside specific regions to prevent last-minute swaying of voters. Despite these constraints, campaigns are fiercely competitive, with parties deploying door-to-door canvassing, social media blitzes, and televised debates to sway undecided voters. The 2015 election, for instance, saw the Liberals’ “Real Change” message resonate widely, catapulting them from third place to a majority government in a single campaign cycle.

A critical takeaway from Canada’s electoral process is its emphasis on local representation over proportional outcomes. While FPTP can distort the relationship between votes and seats, it fosters a direct link between MPs and their constituents. This dynamic encourages politicians to address local issues, such as infrastructure or regional economies, alongside national priorities. However, it also marginalizes smaller parties and can lead to strategic voting, where electors back a candidate not out of preference but to block another. For voters, understanding this system is key to navigating its quirks, whether by supporting electoral reform or engaging in campaigns to amplify their voice within the existing framework.

Gracefully Canceling Interviews: Professional Tips for Polite Declination

You may want to see also

Federal-Provincial Relations: Power division, provincial autonomy, and intergovernmental cooperation

Canada’s federal system is a delicate balance of shared and divided powers, enshrined in the Constitution Act, 1867. The federal government holds authority over areas like national defense, foreign affairs, and currency, while provinces control education, healthcare, and natural resources. This division isn’t static; it’s a living framework shaped by historical compromises, court rulings, and political negotiations. For instance, while Ottawa sets immigration targets, provinces like Quebec wield significant control over immigrant selection, reflecting their unique cultural and linguistic priorities. This power division ensures that neither level of government can dominate, fostering a system where collaboration is often necessary to address national challenges.

Provincial autonomy is a cornerstone of Canadian federalism, allowing provinces to tailor policies to their distinct needs. Alberta’s energy-driven economy, for example, contrasts sharply with Quebec’s focus on cultural preservation and hydroelectric power. This autonomy, however, can lead to friction. Provinces frequently challenge federal initiatives they perceive as overreach, such as the carbon tax, which several provinces contested in court. Yet, autonomy also enables innovation. British Columbia’s pioneering carbon tax and Ontario’s healthcare reforms serve as models for other jurisdictions, demonstrating how decentralized power can drive progress.

Intergovernmental cooperation is the glue that holds Canada’s federal system together, particularly in areas of shared jurisdiction like the environment and social programs. Mechanisms like the First Ministers’ Meetings and fiscal transfers (e.g., the Canada Health Transfer) facilitate dialogue and resource sharing. However, cooperation isn’t always smooth. Negotiations over equalization payments, which redistribute wealth from richer to poorer provinces, often expose regional tensions. Despite these challenges, successful collaborations, such as the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, highlight the potential for joint action when interests align.

Practical tips for understanding federal-provincial dynamics include tracking key court cases, like *Reference re Same-Sex Marriage* (2004), which clarified federal-provincial jurisdiction over marriage laws. Monitoring fiscal arrangements, such as the Canada Social Transfer, reveals how Ottawa influences provincial priorities. Finally, observing provincial responses to federal initiatives, like the recent childcare agreements, provides insight into the bargaining power of smaller provinces. By focusing on these specifics, one can grasp the nuanced interplay between federal authority, provincial autonomy, and intergovernmental cooperation in Canada’s political system.

Money in Politics: Corruption, Influence, and Democracy at Stake

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Political Parties: Major parties (Liberal, Conservative, NDP), ideologies, and party dynamics

Canada's political landscape is dominated by three major parties: the Liberal Party, the Conservative Party, and the New Democratic Party (NDP). Each party brings distinct ideologies and strategies to the table, shaping the country’s policies and public discourse. Understanding their differences is key to navigating Canadian politics.

The Liberal Party, historically centrist with a progressive tilt, emphasizes social justice, multiculturalism, and fiscal responsibility. Liberals often champion initiatives like healthcare funding, environmental protection, and social programs. For instance, their carbon pricing plan reflects a commitment to combating climate change while balancing economic growth. However, critics argue their policies can be vague, prioritizing political pragmatism over ideological purity. This flexibility has allowed them to appeal to a broad electorate, making them a dominant force in Canadian politics.

In contrast, the Conservative Party leans right, advocating for lower taxes, reduced government intervention, and a focus on individual freedoms. Conservatives often prioritize economic growth, law and order, and traditional values. Their opposition to carbon taxes and support for pipeline projects highlight their pro-business stance. Yet, internal divisions between social conservatives and fiscal hawks sometimes weaken their unity. This ideological split can make it challenging to present a cohesive vision, particularly in diverse regions like Quebec and urban centers.

The NDP occupies the left flank, rooted in social democracy and labor rights. They advocate for wealth redistribution, universal healthcare expansion, and workers’ rights. For example, their push for pharmacare aims to address gaps in Canada’s healthcare system. While the NDP has never formed a federal government, they often hold the balance of power in minority parliaments, influencing policy from the sidelines. However, their struggle to appeal beyond urban and unionized voters limits their national reach.

Party dynamics in Canada are further complicated by regional interests and minority governments. The Liberals and Conservatives often compete for the center, while the NDP seeks to pull the agenda leftward. Strategic voting and coalition-building are common, particularly in tight races. For instance, the 2021 federal election saw the NDP prop up a Liberal minority government, securing concessions on dental care and housing. Such alliances underscore the fluidity and negotiation inherent in Canada’s multiparty system.

In practice, voters must weigh these parties’ ideologies against regional priorities. For example, a voter in Alberta might prioritize a party’s stance on energy policy, while a Quebec voter may focus on language rights. Understanding these nuances allows citizens to engage meaningfully in the political process, ensuring their voices align with the party best representing their values.

Tourism and Politics: Exploring the Complex Interplay of Power and Travel

You may want to see also

Judicial System: Role of courts, Supreme Court, and constitutional interpretation in politics

Canada’s judicial system is the backbone of its political framework, ensuring laws align with constitutional principles and protecting individual rights. At its apex sits the Supreme Court of Canada, the final arbiter of legal disputes and constitutional interpretation. Unlike the U.S. Supreme Court, which often wades into overtly political battles, Canada’s highest court operates with a focus on legal clarity and precedent, though its decisions inevitably shape policy and societal norms. For instance, the 2015 *Carter v. Canada* decision decriminalized physician-assisted dying, forcing Parliament to draft new legislation within a court-imposed timeline. This example illustrates how the judiciary can catalyze legislative action while remaining independent of political pressures.

The role of courts in Canadian politics extends beyond the Supreme Court. Lower courts, such as provincial superior courts and federal courts, interpret laws and resolve disputes that often have political implications. For example, challenges to environmental regulations or Indigenous land claims frequently end up in these courts, where judges must balance legal principles with broader societal interests. This layered system ensures that constitutional interpretation is not confined to a single institution, fostering a more nuanced approach to justice. However, this decentralization also means that inconsistent rulings can occur, highlighting the need for the Supreme Court’s unifying role.

Constitutional interpretation in Canada is guided by the *Living Tree Doctrine*, which holds that the Constitution must adapt to evolving societal values. This approach contrasts with originalist interpretations seen in other jurisdictions and allows the judiciary to address contemporary issues like LGBTQ+ rights or climate change within a historical framework. A prime example is the *R. v. Oakes* (1986) decision, which established a test for balancing individual rights against reasonable limits under the *Charter of Rights and Freedoms*. This flexibility ensures the Constitution remains relevant but also invites criticism that judicial activism undermines legislative authority.

Despite its independence, the judiciary is not immune to political influence. Judicial appointments, particularly to the Supreme Court, are made by the federal government, raising questions about impartiality. However, Canada’s appointment process includes rigorous consultation, and justices are expected to uphold the law, not partisan interests. For instance, Justice Rosalie Abella, appointed in 2004, was widely respected for her impartiality and contributions to human rights law, demonstrating how the system can function effectively even within a political context.

In practice, understanding the judicial system’s role requires recognizing its dual nature: as a check on political power and as a facilitator of societal change. Citizens engaging with the system should focus on how court decisions impact policy, such as the *Reference re Same-Sex Marriage* (2004), which paved the way for federal legalization. Advocates and policymakers must also navigate the tension between judicial interpretation and legislative intent, ensuring laws are both constitutional and practical. Ultimately, the judiciary’s role in Canadian politics is to safeguard democracy, not dictate it, making it a vital yet measured force in the nation’s governance.

Withdrawing Your Application Gracefully: A Guide to Polite Professional Exits

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Canada operates as a parliamentary democracy and a constitutional monarchy, with the British monarch as the head of state, represented by the Governor General. Its government is structured around a multi-party system, and the Prime Minister is the head of government, typically the leader of the party with the most seats in the House of Commons. Unlike the U.S., Canada does not have a presidential system, and its federal structure includes shared powers between the federal and provincial governments.

The Prime Minister is the most powerful political figure in Canada, serving as the head of government and chair of the Cabinet. They are typically the leader of the party with the most seats in the House of Commons and are responsible for setting policy direction, appointing ministers, and representing Canada on the international stage. The Prime Minister also advises the Governor General on matters such as calling elections and appointing senators.

MPs are elected through a first-past-the-post system in single-member constituencies, known as ridings. Voters in each riding cast ballots for their preferred candidate, and the candidate with the most votes wins the seat, regardless of whether they have a majority. This system can lead to a party forming a majority government without winning a majority of the popular vote.

The Senate is the upper house of Canada's Parliament and acts as a chamber of "sober second thought," reviewing and amending legislation passed by the House of Commons. Senators are appointed by the Governor General on the advice of the Prime Minister, typically to represent regional interests. Unlike the House of Commons, the Senate does not initiate financial legislation and has limited power to reject bills, making it less influential in day-to-day politics.