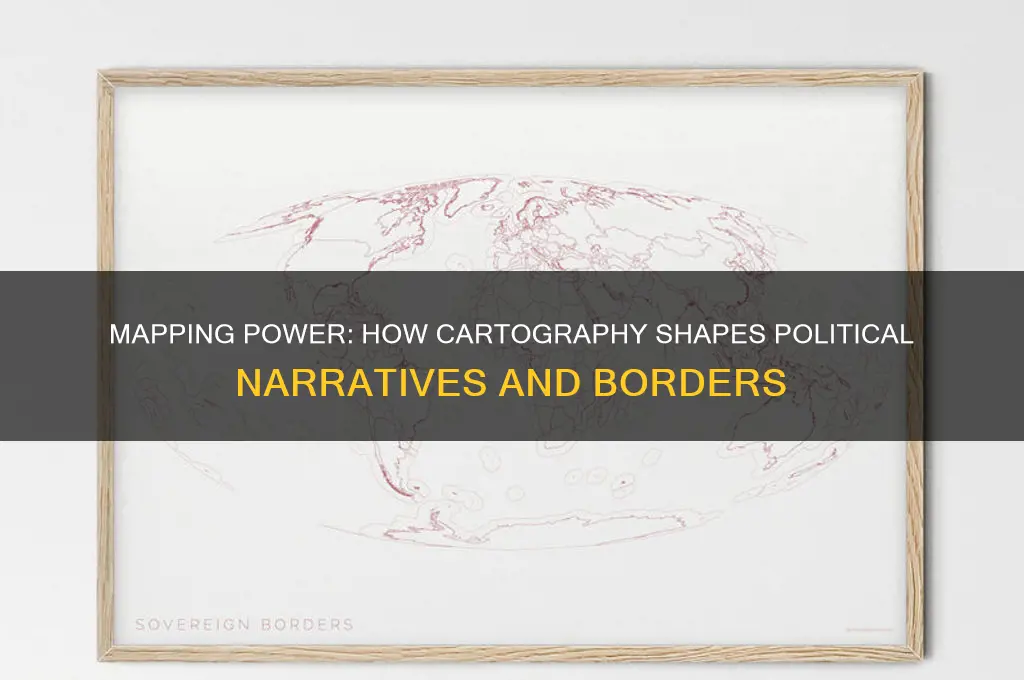

Maps are inherently political tools that reflect and reinforce power dynamics, ideologies, and territorial claims. While they appear objective, their creation involves selective representation, often omitting or emphasizing certain features to serve specific agendas. For instance, borders on maps are not neutral lines but products of historical conflicts, treaties, and negotiations, legitimizing control over territories. Additionally, the projection systems used to depict the Earth’s surface can distort sizes and shapes, privileging certain regions over others, such as the Mercator projection, which enlarges Europe and North America. Maps also exclude or marginalize indigenous lands, disputed areas, and alternative narratives, perpetuating dominant perspectives. Thus, maps are not just navigational aids but instruments of political influence, shaping how we perceive the world and who holds authority within it.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Border Disputes: How mapmakers depict contested territories reflects political biases and national interests

- Naming Conventions: Place names on maps often reflect dominant political or cultural perspectives

- Scale & Projection: Map projections can distort size, emphasizing or diminishing political power

- Resource Representation: Maps highlight resources like oil or minerals, influencing geopolitical strategies

- Historical Narratives: Maps reinforce political histories, often omitting marginalized groups or alternative stories

Border Disputes: How mapmakers depict contested territories reflects political biases and national interests

Maps are not neutral artifacts; they are imbued with the perspectives and priorities of their creators. This is nowhere more evident than in the depiction of border disputes, where contested territories become battlegrounds not just on the ground but also on paper (or screens). Consider the ongoing dispute between India and Pakistan over Kashmir. Indian maps invariably show the entire region as part of India, while Pakistani maps claim it as their own. These conflicting representations are not mere cartographic errors but deliberate statements of national sovereignty and political ambition.

To understand how mapmakers navigate these disputes, consider the following steps. First, identify the contested territory and research the historical and legal claims of each party. Second, examine how maps from different countries or organizations depict the area—do they use dashed lines, shading, or labels to indicate ambiguity? Third, analyze the language and symbols used. For instance, labeling a disputed island as "Diaoyu Islands" (Chinese) versus "Senkaku Islands" (Japanese) immediately signals political allegiance. This process reveals how maps serve as tools for reinforcing national narratives rather than objective records of geography.

A persuasive argument can be made that mapmakers often prioritize their own nation’s interests, even at the expense of accuracy. Take the case of the South China Sea, where China’s "nine-dash line" appears on many Chinese maps, asserting broad territorial claims despite international legal challenges. This depiction is not just a cartographic choice but a political statement, one that influences public perception and diplomatic negotiations. Conversely, maps produced by the U.S. or ASEAN countries often omit this line, reflecting their rejection of China’s claims. Such discrepancies highlight how maps can perpetuate or challenge geopolitical tensions.

Comparatively, some mapmakers attempt to remain neutral by using visual cues to denote disputed areas. Dashed lines, for example, are commonly used to indicate borders that are not internationally recognized. However, even this seemingly impartial approach can be biased. The placement and thickness of these lines, or the decision to include or exclude certain labels, can subtly favor one party over another. For instance, a map that places a dashed line closer to one country’s claimed territory may inadvertently lend it more legitimacy. This underscores the challenge of true neutrality in cartography.

In conclusion, the depiction of border disputes on maps is a powerful reflection of political biases and national interests. Whether through bold claims, subtle visual cues, or deliberate omissions, mapmakers shape how we perceive territorial conflicts. For those analyzing maps, it’s crucial to question their sources and scrutinize their details. For those creating maps, the responsibility lies in balancing national narratives with a commitment to accuracy and fairness. After all, in the world of cartography, every line drawn is a statement made.

Do Politics Ajeet Bharti: Unveiling the Impact and Influence

You may want to see also

Naming Conventions: Place names on maps often reflect dominant political or cultural perspectives

Place names are not neutral labels; they are powerful tools that shape our understanding of geography and history. Consider the city of Istanbul, known as Constantinople during the Byzantine and Ottoman Empires. The shift in name reflects not just a linguistic change but a profound political transformation, marking the rise of a new empire and the decline of an old one. This example underscores how naming conventions on maps can encapsulate and perpetuate dominant political narratives.

To analyze this further, examine the renaming of cities after political upheavals. For instance, St. Petersburg became Petrograd in 1914 to sound less German during World War I, then Leningrad in 1924 to honor Vladimir Lenin, and finally reverted to St. Petersburg in 1991 following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Each change was a deliberate act of political rebranding, aimed at aligning the city’s identity with the ruling ideology. Cartographers, whether intentionally or not, become agents of this rebranding by adopting these new names on maps, thereby normalizing them for global audiences.

A persuasive argument can be made that place names on maps often erase indigenous or minority cultures. Take the case of Mount Denali in Alaska, originally named by the Athabascan people as "Deenaalee," meaning "the tall one." In 1896, a prospector renamed it Mount McKinley to honor a U.S. president. This name persisted on maps for over a century, despite protests from Alaska’s indigenous communities. Only in 2015 was the original name restored, highlighting the political struggle embedded in cartographic naming conventions. This example illustrates how maps can either marginalize or validate cultural identities based on whose perspective dominates.

Comparatively, the naming of bodies of water also reveals political biases. The Persian Gulf, for instance, has been a point of contention between Iran and Arab states, with some maps labeling it the "Arabian Gulf." This discrepancy is not merely linguistic but reflects geopolitical rivalries and cultural assertions. Cartographers must navigate these disputes carefully, as their choices can inadvertently take sides in international conflicts. The takeaway here is clear: the names on maps are not just descriptors but declarations of power and identity.

Practically speaking, educators and map users can challenge dominant naming conventions by adopting inclusive practices. For example, when teaching geography, present multiple names for a location (e.g., Mumbai/Bombay, Yangon/Rangoon) and discuss their historical and cultural contexts. Encourage critical thinking by asking students to research the origins of place names and their political implications. By doing so, we can transform maps from instruments of dominance into tools for understanding diverse perspectives. This approach not only enriches geographical literacy but also fosters a more equitable worldview.

Modern Politics: Digital Campaigns, Global Influence, and Evolving Governance

You may want to see also

Scale & Projection: Map projections can distort size, emphasizing or diminishing political power

Maps are not neutral tools; they are shaped by the choices of their creators, and these choices can have profound political implications. One of the most significant ways this occurs is through scale and projection, which can subtly or dramatically distort the size of territories, thereby emphasizing or diminishing political power. Consider the Mercator projection, widely used in schools and media. While it preserves the shapes of countries, it grossly inflates the size of regions near the poles, such as Greenland and Antarctica, making them appear larger than continents like Africa or South America. This visual distortion can perpetuate misconceptions about global power dynamics, implicitly elevating the perceived importance of certain nations over others.

To understand the political impact of such distortions, imagine a map used in international negotiations. A projection that exaggerates the size of a country might unconsciously influence perceptions of its geopolitical influence, potentially swaying diplomatic discussions in its favor. Conversely, a map that minimizes the size of a nation could undermine its claims to resources or sovereignty. For instance, the Peters projection, which prioritizes area accuracy, reveals how much smaller countries like the United States or Russia appear when compared to their Mercator representations. This shift in visual emphasis challenges established narratives and can rebalance the political discourse.

Choosing a map projection is not a technical decision alone; it is a political act. Cartographers must weigh the purpose of the map against the inherent biases of different projections. For example, the Gall-Peters projection is often used in educational settings to counteract the Eurocentric bias of the Mercator projection, but it distorts shapes, making countries look stretched or squashed. This trade-off highlights the impossibility of creating a perfectly neutral map. Instead, the goal should be transparency: clearly labeling the projection used and educating viewers about its limitations. This empowers audiences to critically interpret maps rather than accepting them at face value.

Practical steps can mitigate the political manipulation of scale and projection. First, diversify the types of maps used in public and educational contexts. Incorporate multiple projections to provide a more comprehensive view of the world. Second, encourage critical map literacy by teaching how projections work and their potential biases. For instance, a classroom activity could involve comparing the same region across different projections to illustrate how size and shape can vary. Finally, advocate for the use of dynamic digital maps, which allow users to switch between projections and scales, offering a more interactive and nuanced understanding of geography. By taking these steps, we can reduce the unintended—or intentional—political distortions embedded in static maps.

In conclusion, scale and projection are not mere technical details but powerful tools that shape our understanding of the world. Their misuse can reinforce political hierarchies, while their thoughtful application can challenge them. By recognizing the political implications of map design and adopting strategies to address them, we can create more equitable and informed representations of our global landscape. Maps are not just reflections of reality; they are instruments of perception, and their creation demands both precision and responsibility.

Uncovering Political Contributions: A Step-by-Step Guide to Tracking Donations

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Resource Representation: Maps highlight resources like oil or minerals, influencing geopolitical strategies

Maps are not merely geographical tools; they are powerful instruments of political influence, especially when it comes to resource representation. By highlighting the presence of valuable resources like oil, minerals, or rare earth elements, maps can shape geopolitical strategies, economic policies, and even international conflicts. Consider the Middle East, where maps detailing oil reserves have historically been central to global power dynamics. These visual representations do more than inform—they direct attention, allocate priorities, and often dictate the flow of capital and military intervention.

To understand the political weight of resource representation, examine how maps are constructed and disseminated. Cartographers must decide what to include, exclude, or emphasize, a process that is rarely neutral. For instance, a map might highlight oil fields in a disputed territory, subtly reinforcing claims by one nation over another. This selective representation can legitimize geopolitical maneuvers, such as resource exploitation or territorial annexation. Governments and corporations alike use these maps to justify their actions, often at the expense of local populations or environmental sustainability.

A practical example illustrates this point: the Arctic. As ice melts due to climate change, maps increasingly depict newly accessible mineral deposits and shipping routes. These representations fuel competition among nations like Russia, Canada, and the United States, each staking claims based on cartographic evidence. Here, maps are not just tools for navigation but instruments of negotiation, used in diplomatic talks and international law disputes. They transform abstract geopolitical ambitions into tangible, visually compelling arguments.

However, the political use of resource maps is not without risks. Overemphasis on exploitable resources can marginalize other critical factors, such as ecological impact or indigenous rights. For instance, maps focusing on coal reserves in Appalachia often omit the human and environmental costs of extraction. This narrow focus can mislead policymakers and the public, perpetuating unsustainable practices. To counter this, advocates for transparency urge the inclusion of layered data—environmental degradation, population displacement, and long-term economic viability—alongside resource locations.

In conclusion, resource representation on maps is a double-edged sword. While it provides essential information for strategic planning, it also wields significant political power, shaping narratives and driving actions that can have far-reaching consequences. To use these maps responsibly, one must critically evaluate their sources, methodologies, and biases. By doing so, we can ensure that resource representation serves not just narrow interests but the broader goals of equity, sustainability, and global cooperation.

Navigating Political Conversations: Strategies for Therapists to Stay Neutral and Effective

You may want to see also

Historical Narratives: Maps reinforce political histories, often omitting marginalized groups or alternative stories

Maps, as seemingly objective tools, often embed historical narratives that reflect dominant political perspectives. Consider the Mercator projection, a common map design that distorts the size of continents, enlarging Europe and North America while minimizing Africa and South America. This visual hierarchy subtly reinforces a Eurocentric worldview, echoing colonial-era narratives of power and dominance. Such representations are not accidental; they are choices that prioritize certain histories over others, often at the expense of marginalized groups.

To illustrate, examine how Native American territories are depicted on historical maps of the United States. Early maps frequently erased tribal lands, labeling vast regions as "uninhabited" or "wilderness," despite the presence of indigenous communities. This erasure served political agendas, justifying land seizures and displacement. Even modern maps often fail to acknowledge these histories, perpetuating a narrative of manifest destiny that sidelines Native American experiences. Educators and cartographers can counteract this by incorporating maps that highlight indigenous territories, such as the Native Land Digital project, which restores visibility to these erased histories.

The omission of alternative narratives is not limited to colonial contexts. For instance, maps of the Middle East often reflect geopolitical boundaries drawn by European powers during the 20th century, ignoring centuries of cultural and ethnic diversity. This reinforces a fragmented view of the region, aligning with Western political interests rather than local realities. By contrast, maps that depict historical trade routes or cultural networks offer a more inclusive perspective, emphasizing shared histories over imposed divisions. Cartographers should prioritize such representations to challenge dominant narratives.

Practical steps can be taken to address these biases. First, diversify map sources by consulting indigenous, local, or minority-produced cartography. Second, critically evaluate map projections and symbols, questioning their origins and implications. Third, encourage educational institutions to teach map literacy, helping students recognize and question political biases in geographic representations. By doing so, maps can become tools for reclaiming marginalized histories rather than instruments of erasure.

Ultimately, the political nature of maps lies in their ability to shape perceptions of the past and present. By acknowledging and challenging their biases, we can use maps to amplify silenced voices and foster a more inclusive understanding of history. This requires intentional effort, but the result—a more equitable representation of our world—is well worth the endeavor.

Is 'Here You Go' Polite? Exploring Everyday Phrases and Etiquette

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Maps are political because they reflect the perspectives, biases, and agendas of those who create them. They often emphasize certain borders, territories, or names while omitting or downplaying others, shaping how people perceive geopolitical realities.

Yes, the scale and projection of a map can be political. For example, the Mercator projection enlarges regions near the poles, like Europe and North America, while shrinking equatorial regions, like Africa. This can subtly reinforce Eurocentric viewpoints.

Borders on maps are political because they represent agreements, conflicts, or claims between nations or groups. Their depiction can legitimize certain territorial claims or disputes, influencing public and international perceptions of sovereignty.

Maps influence political identity by defining "us" versus "them" through borders, labels, and symbols. They can reinforce national narratives, shape cultural identities, and even contribute to tensions or unity between different groups.

![32"x24" Detailed political and geographical map of Nepal with legend [Laminated]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/81U0cIG5p+L._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![Geographical historical political philosophical and mechanical essays the first, containing an analysis of a general map of the middle British colonies in America 1755 [Hardcover]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/518Uvpx2g2L._AC_UY218_.jpg)