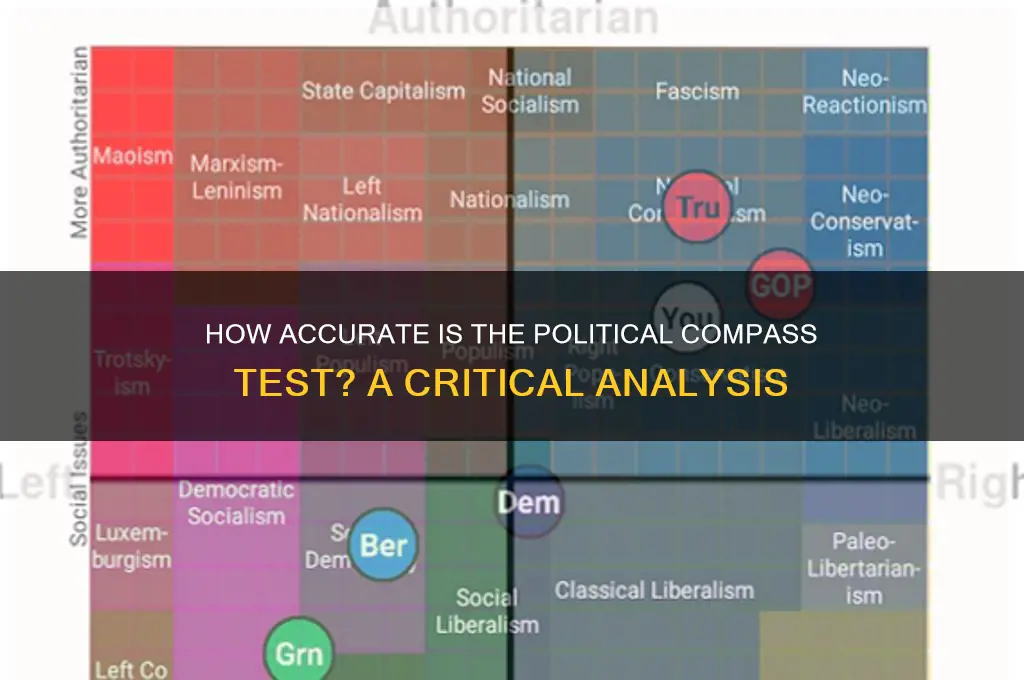

The Political Compass, a popular online tool designed to map individuals' political beliefs on a two-dimensional grid, has gained widespread attention for its simplicity and accessibility. However, its accuracy has been a subject of debate among political scientists and users alike. While the test attempts to measure both economic and social attitudes, critics argue that its methodology oversimplifies complex political ideologies, often failing to capture nuanced perspectives. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported answers and the potential for biased question framing raise concerns about its reliability. Despite these limitations, the Political Compass remains a useful starting point for self-reflection and discussion, though it should be approached with an understanding of its inherent constraints.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Subjectivity | High. Results depend on personal interpretation of questions and limited question scope. |

| Simplification | Oversimplifies complex political ideologies into two axes (Economic and Social). |

| Question Bias | Questions can be leading or lack nuance, potentially skewing results. |

| Cultural Bias | Primarily Western-centric, may not accurately reflect non-Western political contexts. |

| Static Nature | Doesn't account for evolving political beliefs or contextual factors. |

| Entertainment Value | Popular for sparking discussion and self-reflection, but not a definitive measure. |

| Alternative Tools | More comprehensive tests exist (e.g., 8values, Political Coordinates Test) but still have limitations. |

| Accuracy for Broad Categorization | Can provide a general idea of where someone falls on the traditional left-right and authoritarian-libertarian spectrums. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Methodology Critique: Examines the validity of questions and scoring algorithms used in the political compass test

- Cultural Bias: Explores how cultural contexts may skew results, favoring Western political ideologies

- Limited Dimensions: Discusses if two axes (economic, social) can accurately capture complex political beliefs

- User Interpretation: Analyzes how personal biases affect how users interpret and apply their results

- Consistency Over Time: Questions whether political compass results remain stable or change with evolving views

Methodology Critique: Examines the validity of questions and scoring algorithms used in the political compass test

The Political Compass Test, a popular online tool for mapping political beliefs, relies heavily on its methodology—specifically, the questions it poses and the algorithms it uses to score responses. A critical examination of these elements reveals both strengths and limitations in its validity. The test employs a series of 62 statements to which users respond on a strongly agree/disagree scale. While this format appears straightforward, the phrasing of questions often lacks nuance, reducing complex political ideologies to binary choices. For instance, a statement like "The free market is the best arbiter of what is good for society" oversimplifies economic philosophies, potentially misclassifying users who hold nuanced views on capitalism and regulation.

The scoring algorithm further complicates matters. Responses are plotted on a two-dimensional graph, with axes representing economic and social attitudes. However, the weighting of questions remains opaque. Users are left to wonder whether certain statements carry more influence in determining their position. For example, a single strongly worded question about taxation might disproportionately skew a user’s economic score, even if their overall views are more balanced. This lack of transparency undermines the test’s credibility, as users cannot verify whether their results accurately reflect their beliefs.

A comparative analysis of similar tools highlights additional concerns. Unlike academic surveys, which often include demographic questions to contextualize responses, the Political Compass Test operates in a vacuum. This omission ignores the intersectionality of political beliefs with factors like age, education, and geographic location. For instance, a young urban professional and a rural retiree might answer identically but hold vastly different political priorities. Without this context, the test risks oversimplifying the diversity of political thought.

To improve its validity, the Political Compass Test could adopt several practical measures. First, questions should be revised to incorporate more nuanced language, allowing users to express gradations of agreement or disagreement. Second, the scoring algorithm should be made transparent, detailing how each question contributes to the final result. Third, incorporating demographic questions could provide a richer understanding of users’ political contexts. By addressing these methodological flaws, the test could better serve as a tool for meaningful self-reflection rather than a superficial label generator.

Understanding the Complexities of the US Political System: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Cultural Bias: Explores how cultural contexts may skew results, favoring Western political ideologies

The Political Compass test, a popular tool for mapping individuals' political beliefs, often assumes a universal framework of left-right and authoritarian-libertarian axes. However, this framework is deeply rooted in Western political history, particularly the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. For instance, the left-right axis, which traditionally distinguishes between egalitarianism and free markets, may not resonate in cultures where collective identity or hierarchical structures are more central. In many non-Western societies, political discourse revolves around issues like communal harmony, ancestral traditions, or religious law, which the Political Compass fails to capture. This inherent bias toward Western ideologies can lead to misinterpretations of political beliefs in diverse cultural contexts.

Consider the concept of individualism, a cornerstone of Western political thought and a key factor in the libertarian-authoritarian axis. In collectivist cultures, such as those in East Asia or Africa, the emphasis on community welfare over personal freedom may skew results toward "authoritarianism," even if the individual supports policies that prioritize social cohesion rather than state control. For example, a person advocating for strong family or community-based governance might be mislabeled as favoring authoritarianism simply because their values do not align with Western notions of individual liberty. This misalignment highlights how the Political Compass’s framework can misrepresent non-Western political ideologies as deviations from a Western norm.

To illustrate, let’s examine the treatment of economic policies in the Political Compass. The left-right axis often equates "left" with state intervention and "right" with free markets, a dichotomy shaped by Western debates like those between socialism and capitalism. However, in countries like India or Brazil, economic policies often blend market mechanisms with state-led development, reflecting unique historical and cultural priorities. The Political Compass’s binary framework struggles to accommodate such hybrid models, potentially pigeonholing individuals into categories that do not reflect their nuanced beliefs. This limitation underscores the need for culturally sensitive tools that recognize diverse political traditions.

A practical step to mitigate cultural bias is to contextualize the Political Compass within specific cultural frameworks. For instance, when interpreting results from non-Western participants, supplement the test with questions tailored to local political discourses. In Japan, for example, include inquiries about the role of consensus-building or corporate responsibility, which are central to Japanese political culture. Similarly, in the Middle East, incorporate questions about the interplay between religious law and governance. Such adaptations can provide a more accurate representation of political beliefs by acknowledging the cultural contexts that shape them.

Ultimately, while the Political Compass offers a useful starting point for understanding political ideologies, its cultural bias limits its accuracy in non-Western contexts. By recognizing this limitation and adapting the tool to reflect diverse political traditions, we can move toward a more inclusive and nuanced understanding of global political beliefs. Without such adjustments, the Political Compass risks perpetuating a Western-centric view of politics, overlooking the rich tapestry of ideologies that exist beyond its framework.

Is Germany's Political Landscape Stable? Analyzing Current Trends and Challenges

You may want to see also

Limited Dimensions: Discusses if two axes (economic, social) can accurately capture complex political beliefs

The Political Compass, with its two axes—economic and social—offers a simplified framework for understanding political beliefs. However, this reductionist approach raises questions about its ability to capture the intricate nuances of individual ideologies. Consider the economic axis, which ranges from left (state control) to right (free market). While it effectively distinguishes between socialism and capitalism, it fails to account for variations within these broad categories. For instance, a supporter of Nordic-style social democracy and a Marxist-Leninist both fall on the left, yet their economic visions differ drastically in terms of private property, market regulation, and wealth redistribution. This oversimplification risks grouping disparate beliefs under a single label, losing critical distinctions.

To illustrate the limitations of the social axis, examine the spectrum from authoritarian (restriction of personal freedoms) to libertarian (maximal individual liberty). This axis struggles to address the complexity of social issues, such as the balance between security and privacy or the role of cultural norms in shaping policy. For example, a socially conservative individual might advocate for traditional values while also supporting robust civil liberties, defying easy categorization. Similarly, a progressive might endorse government intervention in promoting equality but oppose overreach in personal matters. These contradictions highlight the inadequacy of a single dimension to encapsulate the multifaceted nature of social beliefs.

A practical exercise to test the Political Compass’s limitations is to apply it to real-world scenarios. Take the issue of climate change: a left-leaning individual might support government-led green initiatives, while a right-leaning one could favor market-driven solutions. However, both might agree on the urgency of action, blurring the economic axis’s utility. On the social axis, a libertarian might oppose government mandates on emissions but support community-led environmental efforts, while an authoritarian might enforce strict regulations without addressing individual freedoms. These examples demonstrate how two axes cannot fully capture the interplay of economic and social factors in complex policy areas.

To improve the accuracy of such models, consider expanding the dimensions to include additional axes, such as globalism vs. nationalism or environmentalism vs. industrialism. For instance, a three-axis model could better differentiate between a left-leaning environmentalist who supports global cooperation and a right-leaning nationalist who prioritizes domestic industry. While this increases complexity, it provides a more granular understanding of political beliefs. Alternatively, qualitative assessments—such as detailed questionnaires or interviews—can complement quantitative models by exploring the reasoning behind beliefs, offering a richer, more nuanced portrait of individual ideologies.

In conclusion, while the Political Compass serves as a useful starting point for understanding political beliefs, its reliance on two axes inherently limits its accuracy. By acknowledging these constraints and exploring supplementary methods, we can move toward a more comprehensive framework that respects the complexity of human ideology. For those seeking a deeper understanding, combining quantitative tools with qualitative analysis offers a more robust approach to mapping the political landscape.

Do Political Labels Still Matter in Today's Polarized Landscape?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

User Interpretation: Analyzes how personal biases affect how users interpret and apply their results

Personal biases act as invisible lenses, distorting how individuals perceive and apply their Political Compass results. Consider a user who scores high on the authoritarian scale. Their initial reaction might be defensive, dismissing the result as inaccurate or blaming the test’s methodology. This denial stems from cognitive dissonance—the discomfort of holding conflicting beliefs. Instead of reflecting on behaviors that align with authoritarian tendencies, such as valuing order over individual freedoms, they might cherry-pick examples where they acted democratically, reinforcing their self-image as fair-minded. This selective interpretation undermines the test’s utility, turning it into a tool for confirmation rather than introspection.

To mitigate bias, users should adopt a structured approach when analyzing their results. Start by defining each axis (economic, social, authoritarian vs. libertarian) in neutral terms, avoiding loaded language. For instance, instead of labeling a left-leaning economic score as "socialist," describe it as prioritizing collective welfare over free-market principles. Next, cross-reference the results with real-world examples. If someone scores as socially progressive, compare their views on issues like LGBTQ+ rights or immigration to those of known progressive figures or policies. This external validation helps ground the results in reality, reducing the temptation to reinterpret them through a biased lens.

A persuasive argument for self-awareness is the "bias audit." Before accepting or rejecting Political Compass results, users should list their preconceived notions about political ideologies. For example, someone who associates conservatism with moral superiority might unconsciously skew their interpretation to align with that belief. By acknowledging these biases upfront, individuals can actively challenge them. Ask: "Am I rejecting this result because it conflicts with my identity, or because it’s genuinely inaccurate?" This critical self-questioning transforms the test from a personality quiz into a tool for intellectual honesty.

Comparing the Political Compass to other frameworks can also reveal biases. For instance, someone who identifies as centrist might feel validated by a moderate score but overlook how their views on specific issues (e.g., taxation or free speech) lean more left or right. Pairing the test with issue-based surveys or historical political figures can provide context. If a user’s economic views align with FDR’s New Deal policies, they might be more left-leaning than they initially thought. This comparative analysis forces users to confront inconsistencies between their self-perception and their actual beliefs.

Finally, practical tips can enhance unbiased interpretation. Set a "cooling-off period" after receiving results—wait 24 hours before analyzing them to reduce emotional reactivity. Engage in discussions with individuals from different political backgrounds to test the validity of your interpretations. For example, if you score as libertarian, debate a socialist on economic policies to see if your views hold up under scrutiny. Documenting your initial reaction and revisiting it after further research can also highlight how biases evolve. By treating the Political Compass as a starting point for dialogue rather than a definitive label, users can transform potential bias into an opportunity for growth.

Global Affairs Politics: Navigating Complexities in an Interconnected World

You may want to see also

Consistency Over Time: Questions whether political compass results remain stable or change with evolving views

Political compass results are often treated as static snapshots of one’s ideology, but the question of their consistency over time remains underexplored. Individuals evolve—shaped by personal experiences, global events, and shifting societal norms—yet the political compass test assumes a fixed ideological framework. For instance, someone who identifies as libertarian at 20 might lean toward social democracy by 40 after witnessing economic inequality firsthand. This raises a critical question: does the test measure enduring principles or transient reactions to current contexts? Without longitudinal studies tracking the same individuals over decades, claims of stability remain speculative.

To assess consistency, consider the test’s methodology. The political compass relies on self-reported responses to polarizing statements, which are inherently influenced by mood, recent news, or even the order of questions. A user taking the test during an election season might skew more authoritarian or libertarian based on temporary anxieties. Practical tip: retake the test under different circumstances—after a major life event, during political calm, or following exposure to diverse viewpoints—to observe variability. If results fluctuate significantly, it suggests the test captures mood more than core beliefs.

Comparatively, other personality assessments, like the Big Five traits, demonstrate relative stability over time, barring extreme life disruptions. The political compass, however, measures beliefs rather than traits, making it more susceptible to external influences. For example, a 2020 study found that 30% of participants shifted their political alignment within five years, often due to economic shifts or generational aging. This volatility challenges the test’s utility as a long-term ideological marker. Caution: avoid using a single result as definitive proof of your political identity; instead, track changes over time to identify patterns.

Persuasively, the political compass’s value lies not in its precision but in its ability to spark self-reflection. If your results shift, analyze why—did your values change, or did your interpretation of the questions evolve? For instance, a younger person might prioritize individual freedoms (libertarian) but later emphasize collective welfare (left-authoritarian) after experiencing systemic failures. This evolution isn’t inaccuracy; it’s growth. Takeaway: use the test as a tool for dialogue with your past and future selves, not as a rigid label.

Descriptively, imagine a 50-year-old revisiting their political compass results from age 25. The earlier test might show strong right-libertarian leanings, while the current one tilts toward centrist-left. This isn’t a failure of the test but a reflection of life’s complexity. Specific instruction: document your results annually alongside a brief journal entry explaining your mindset. Over time, this archive becomes a personal political biography, revealing not just shifts but the reasons behind them. Consistency isn’t the goal—understanding is.

Politics and Law: Understanding Their Interconnected Roles in Society

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Political Compass test provides a general framework for understanding political leanings along two axes (economic and social) but is not scientifically validated. Its accuracy depends on the user's honest and thoughtful responses, though it may oversimplify complex political beliefs.

Yes, Political Compass results can change as individuals evolve in their beliefs or respond differently based on current events or personal experiences. This variability highlights its limitations as a static measure of political ideology.

The Political Compass is designed to be neutral, but some critics argue it may favor Western political frameworks or struggle to accurately represent non-Western or niche ideologies. Its accuracy in these cases may be limited.