A political party is a structured organization that brings together individuals with shared ideologies, goals, and values to influence government policies and gain political power. At its core, a party operates through a hierarchical system, typically led by a chairperson or leader who sets the agenda and represents the party publicly. Members participate in various levels, from grassroots activists to elected officials, working collectively to mobilize voters, fundraise, and campaign for elections. Internal processes, such as primaries or caucuses, determine candidates for public office, while party platforms outline policy positions to attract supporters. Parties also engage in legislative activities, lobbying, and coalition-building to advance their agenda, often adapting strategies to navigate the complexities of the political landscape and maintain relevance in a competitive democratic system.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Leadership Structure | Hierarchical, with elected or appointed leaders (e.g., party chair, secretary). |

| Membership | Voluntary, with members paying dues and participating in activities. |

| Ideology | Core set of beliefs and principles guiding policies and actions. |

| Organization | National, regional, and local branches with defined roles and responsibilities. |

| Funding | Donations from individuals, corporations, and fundraising events; public funding in some countries. |

| Policy Formation | Developed through internal debates, committees, and member input. |

| Campaigning | Mobilizes supporters, runs ads, and organizes rallies to win elections. |

| Candidate Selection | Uses primaries, caucuses, or internal votes to choose candidates. |

| Legislative Role | Advocates for policies and votes as a bloc in legislative bodies. |

| Public Engagement | Communicates with voters through media, social platforms, and town halls. |

| Coalitions | Forms alliances with other parties or groups to achieve common goals. |

| Accountability | Held accountable by members, voters, and internal governance mechanisms. |

| International Affiliations | Joins global party networks (e.g., Socialist International, Liberal International). |

| Technology Use | Utilizes digital tools for fundraising, organizing, and voter outreach. |

| Internal Democracy | Conducts regular elections for leadership and policy decisions. |

| Crisis Management | Addresses scandals, leadership changes, or policy failures through communication and reforms. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Party Structure: Hierarchy, roles, and organization from local to national levels

- Funding Sources: Donations, memberships, and public financing for party operations

- Policy Formation: Ideologies, platforms, and processes for developing party stances

- Campaign Strategies: Tactics, messaging, and mobilization for elections and public support

- Internal Democracy: Leadership elections, primaries, and member participation in decision-making

Party Structure: Hierarchy, roles, and organization from local to national levels

Political parties are not monolithic entities but complex organisms with distinct layers, each serving a unique function. At the heart of this structure is a hierarchical organization that ensures coordination, decision-making, and representation from the grassroots to the national stage. This hierarchy is not merely a chain of command but a dynamic system where roles and responsibilities are carefully delineated to achieve collective goals. Understanding this structure is crucial for anyone seeking to engage with or influence a political party’s operations.

Consider the local level, often the foundation of a party’s strength. Here, precinct or ward committees form the base, comprising volunteers and activists who mobilize voters, organize events, and gather feedback from their communities. These local units are typically led by chairs or coordinators who act as liaisons between the grassroots and higher party echelons. For instance, in the United States, precinct captains play a pivotal role in door-to-door canvassing and voter registration drives, especially during election seasons. Their efforts are amplified by county or district-level organizations, which aggregate local activities and ensure alignment with broader party strategies.

As we move up the hierarchy, state or provincial party organizations emerge as critical hubs. These bodies oversee multiple local units, manage fundraising efforts, and coordinate campaigns for regional elections. They often house specialized roles such as communications directors, policy advisors, and finance officers, each contributing to the party’s operational efficiency. A notable example is the Democratic Party in California, where the state central committee not only supports local campaigns but also shapes policy platforms that resonate with diverse constituencies. This mid-level tier acts as a bridge, translating national priorities into actionable local initiatives while feeding grassroots concerns upward.

At the apex of this structure lies the national party organization, responsible for overarching strategy, branding, and coordination across regions. Here, roles like the party chair, executive director, and national committee members take center stage. Their tasks include setting the party’s agenda, managing relationships with elected officials, and overseeing high-stakes campaigns such as presidential elections. For instance, the Conservative Party in the UK relies on its Board of the Conservative Party to make key decisions on policy direction and candidate selection. This top tier must balance unity with diversity, ensuring that the party’s message resonates across varied demographics and geographic areas.

A critical takeaway is that effective party structure hinges on clear role definitions and seamless communication across levels. Local activists need to feel empowered, mid-level organizers must be resourceful, and national leaders should remain attuned to the ground realities. Parties that master this balance, such as Germany’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU), thrive by fostering a culture of collaboration and accountability. Conversely, those with rigid hierarchies or communication gaps often struggle to mobilize their base or adapt to changing political landscapes. For anyone involved in party politics, understanding and leveraging this structure is key to driving meaningful change.

Hosting Without Drop-Offs: Polite Ways to Set Party Boundaries

You may want to see also

Funding Sources: Donations, memberships, and public financing for party operations

Political parties, the backbone of democratic systems, rely on a trifecta of funding sources to sustain their operations: donations, memberships, and public financing. Each source comes with its own dynamics, benefits, and challenges, shaping how parties function and compete. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for anyone interested in the inner workings of political organizations.

Donations: The Double-Edged Sword

Donations are often the lifeblood of political parties, providing the bulk of their funding. These contributions can come from individuals, corporations, unions, or other organizations. For instance, in the United States, individual donors can contribute up to $3,300 per election cycle to a federal candidate, while Political Action Committees (PACs) can donate up to $5,000. However, this reliance on donations raises ethical concerns. Large contributions from corporations or wealthy individuals can create the perception—or reality—of undue influence, prompting calls for stricter regulations. Parties must navigate this delicate balance, ensuring transparency and accountability while securing the resources needed to campaign effectively.

Memberships: Grassroots Engagement

Membership fees represent a more stable and ideologically aligned funding source. By paying annual dues—typically ranging from $20 to $100, depending on the party and country—members gain a sense of ownership and involvement. For example, the Labour Party in the UK relies heavily on its membership base, which not only provides financial support but also participates in policy development and leadership elections. This model fosters grassroots engagement but limits the party’s reach to those willing and able to pay. Parties adopting this approach must invest in recruitment and retention strategies to maintain a robust membership base.

Public Financing: A Level Playing Field?

Public financing, funded by taxpayers, aims to reduce the influence of private money in politics. Countries like Germany and Sweden provide parties with public funds based on their electoral performance or membership numbers. In the U.S., presidential candidates can opt for public financing if they agree to spending limits. While this system promotes fairness and reduces corruption, it is not without drawbacks. Critics argue that it can stifle competition by favoring established parties and limiting the resources available for campaigns. Additionally, public financing requires broad societal consensus, which can be difficult to achieve in polarized political environments.

Strategic Trade-offs and Best Practices

Parties must strategically balance these funding sources to ensure sustainability and independence. Diversification is key: relying too heavily on one source can leave a party vulnerable. For instance, a party dependent solely on donations risks losing support if a major donor withdraws, while one reliant on public financing may struggle during economic downturns. Best practices include setting clear fundraising goals, leveraging digital tools to expand membership, and advocating for transparent public financing systems. Parties should also engage in ongoing dialogue with stakeholders to address concerns about influence and accountability.

In essence, the funding sources of a political party are not just financial mechanisms but reflections of its values and priorities. By carefully managing donations, memberships, and public financing, parties can build resilient organizations capable of advancing their agendas while maintaining public trust.

Can Political Parties Call You If You're on the No-Call List?

You may want to see also

Policy Formation: Ideologies, platforms, and processes for developing party stances

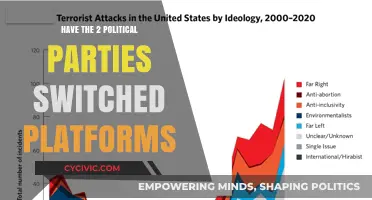

Policy formation within a political party is fundamentally shaped by its core ideologies, which serve as the bedrock for all subsequent decisions. These ideologies—whether conservative, liberal, socialist, or libertarian—dictate the party’s worldview and priorities. For instance, a conservative party might emphasize limited government and free markets, while a socialist party focuses on wealth redistribution and public ownership. Ideologies are not static; they evolve in response to societal changes, economic shifts, and global trends. Parties must balance staying true to their roots with adapting to contemporary challenges, such as climate change or technological disruption. This tension often leads to internal debates, with factions pushing for either tradition or innovation.

Once ideologies are established, parties translate them into platforms—concrete policy proposals that appeal to voters. A platform is more than a list of promises; it’s a strategic document designed to differentiate the party from competitors and mobilize supporters. For example, a party might prioritize healthcare reform by proposing universal coverage, funded through progressive taxation. Crafting a platform involves extensive research, polling, and consultation with experts and stakeholders. Parties must also consider feasibility, ensuring proposals are realistic within budgetary and political constraints. A poorly thought-out platform can alienate voters or invite criticism, while a well-crafted one can define a party’s identity for years.

The process of developing party stances is rarely linear; it involves multiple stages and actors. Typically, it begins with think tanks, policy committees, or working groups drafting proposals based on ideological principles. These drafts are then debated internally, often at party conferences or caucuses, where members from various factions voice their opinions. External input is also crucial, with parties soliciting feedback from interest groups, industry leaders, and the public. For instance, a party might hold town hall meetings to gauge voter sentiment on education reform. Finally, the party leadership synthesizes these inputs into a cohesive stance, balancing ideological purity with political pragmatism.

One critical challenge in policy formation is managing internal dissent. Parties are coalitions of diverse interests, and not everyone will agree on every issue. For example, a centrist party might face resistance from its progressive wing on issues like immigration or environmental regulation. Effective leadership requires navigating these divisions, often through compromise or strategic prioritization. Parties may adopt a “big tent” approach, allowing members to disagree on non-core issues while uniting around shared principles. Alternatively, they might enforce discipline, requiring members to toe the party line. The choice depends on the party’s structure, culture, and electoral strategy.

Ultimately, policy formation is a dynamic, iterative process that reflects a party’s identity and aspirations. It requires a delicate balance between ideological consistency, voter appeal, and practical governance. Parties that master this balance can shape public discourse, influence legislation, and win elections. Those that fail risk irrelevance or fragmentation. For voters, understanding how parties develop their stances offers insight into their values and vision for the future. It’s a window into the machinery of politics, revealing how abstract ideas become tangible policies that impact everyday life.

Do Political Party Affiliations Influence Voting Behavior and Outcomes?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Campaign Strategies: Tactics, messaging, and mobilization for elections and public support

Effective campaign strategies are the lifeblood of any political party's success, blending art and science to sway public opinion and secure electoral victories. At their core, these strategies hinge on three pillars: tactics, messaging, and mobilization. Each element must be meticulously crafted to resonate with target audiences, adapt to the political landscape, and leverage available resources. Without a clear, cohesive approach, even the most well-intentioned campaigns risk fragmentation and ineffectiveness.

Consider the tactical playbook of modern campaigns. Door-to-door canvassing, once the backbone of grassroots efforts, now competes with digital outreach through social media, email, and text messaging. For instance, the 2012 Obama campaign revolutionized micro-targeting by analyzing voter data to deliver personalized messages, increasing turnout among key demographics. However, tactics alone are insufficient. A campaign must also navigate the delicate balance between traditional and digital methods, ensuring that older voters are not alienated while younger audiences remain engaged. Over-reliance on any single tactic can lead to missed opportunities or, worse, voter fatigue.

Messaging is where campaigns articulate their vision, values, and policies in a way that resonates emotionally and intellectually. Successful messaging is concise, consistent, and tailored to the concerns of specific voter groups. For example, the "Yes We Can" slogan of the 2008 Obama campaign encapsulated hope and change, appealing to a broad coalition of voters. Conversely, vague or contradictory messaging can undermine credibility. Campaigns must also anticipate and counter opposition narratives, a strategy known as "prebutting," to control the narrative. A well-crafted message not only informs but also inspires action, turning passive supporters into active advocates.

Mobilization transforms passive support into tangible votes and advocacy. This involves building a robust volunteer network, organizing events, and leveraging endorsements from influencers or community leaders. The 2016 Bernie Sanders campaign exemplified grassroots mobilization, relying on small donations and volunteer-driven rallies to build momentum. However, mobilization requires careful planning and resource allocation. Campaigns must identify high-potential areas for voter registration drives, ensure volunteers are trained, and maintain consistent communication. Neglecting these details can lead to disjointed efforts and wasted energy.

In conclusion, campaign strategies are a dynamic interplay of tactics, messaging, and mobilization, each reinforcing the other to achieve electoral success. By studying past campaigns, adapting to technological advancements, and understanding voter psychology, political parties can craft strategies that not only win elections but also build lasting public support. The key lies in authenticity, adaptability, and a relentless focus on the needs and aspirations of the electorate.

Political Parties as Subcultures: Identity, Ideology, and Social Dynamics Explored

You may want to see also

Internal Democracy: Leadership elections, primaries, and member participation in decision-making

Leadership elections within a political party are the cornerstone of internal democracy, serving as a mechanism to ensure that power is not concentrated in the hands of a few. These elections typically involve party members voting to select their leader, who often becomes the face of the party and its primary candidate for national office. For instance, the Labour Party in the UK employs a one-member-one-vote system, where all members, registered supporters, and affiliated trade union members can participate. This model contrasts with the Conservative Party’s approach, where only Members of Parliament vote in the initial rounds, narrowing the field before a wider membership vote. Such variations highlight how leadership elections can either empower the grassroots or maintain elite control, shaping the party’s identity and direction.

Primaries, a feature more common in countries like the United States, are another critical tool for internal democracy. These are elections open to registered party voters, allowing them to choose the party’s candidate for public office. For example, the Democratic and Republican primaries involve a series of state-by-state contests, culminating in a national convention. Primaries democratize candidate selection by bypassing party elites and giving voters a direct say. However, they can also be costly and divisive, as seen in the 2016 Republican primary, where a crowded field led to bitter infighting. Parties must balance the benefits of inclusivity with the risks of fragmentation when adopting primary systems.

Member participation in decision-making extends beyond leadership and candidate selection to include policy formulation and strategic planning. Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) exemplifies this through its use of member ballots for key decisions, such as coalition agreements. In 2018, SPD members voted on whether to join a grand coalition with Angela Merkel’s CDU, a move that underscored their role in shaping the party’s future. Such practices foster a sense of ownership among members, but they also require robust communication channels and education to ensure informed participation. Parties must invest in training and resources to empower members to contribute meaningfully.

Despite the promise of internal democracy, challenges persist. Low turnout in leadership elections and primaries can undermine their legitimacy, as seen in the 2020 Labour Party leadership election, where only 490,000 out of 580,000 eligible members voted. Additionally, the influence of external factors, such as media coverage or donor pressure, can skew outcomes. To mitigate these risks, parties should adopt transparent processes, encourage diverse participation, and safeguard against undue external influence. Internal democracy is not a one-size-fits-all solution but a dynamic practice that requires continuous adaptation to reflect the values and needs of the party and its members.

Launching a Political Party Donation Business: Strategies for Success

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

A political party is typically structured hierarchically, with local, regional, and national levels. At the local level, there are grassroots members and volunteers. Regional or state-level organizations coordinate activities across districts. The national level includes the party leadership, such as the chairperson, executive committee, and policy-making bodies, which oversee strategy, fundraising, and candidate selection.

Political parties usually select candidates through primaries, caucuses, or internal party conventions. Primaries involve registered voters casting ballots to choose a candidate, while caucuses are meetings where party members discuss and vote for their preferred candidate. In some cases, party leaders or committees may directly appoint candidates based on criteria like electability, loyalty, and alignment with party values.

Political parties play a crucial role in shaping public policy by developing platforms, advocating for specific agendas, and influencing legislation. Once in power, the party in government works to implement its policies, while the opposition party critiques and proposes alternatives. Parties also mobilize public opinion, engage in lobbying, and collaborate with interest groups to advance their policy goals.