Throughout U.S. history, it has been common for a single political party to control both the Senate and the House of Representatives simultaneously, a scenario often referred to as a unified government. This occurs when one party holds a majority in both chambers of Congress, allowing for greater legislative efficiency and alignment with the party’s agenda. Notable examples include the Democratic Party’s dominance during the New Deal era under President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Republican Party’s control during the early years of the George W. Bush administration. However, divided government, where one party controls the White House and the other controls one or both chambers of Congress, is also frequent, leading to checks and balances but often resulting in legislative gridlock. The balance of power between the parties in Congress has shifted repeatedly, reflecting the dynamic and often polarized nature of American politics.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Has a political party ever controlled both the Senate and the House? | Yes, it has happened multiple times in U.S. history. |

| Frequency | Common, especially during periods of strong partisan alignment. |

| Most Recent Example | Democrats controlled both chambers from 2021 to 2023 (117th Congress). |

| Longest Continuous Control | Democrats held both chambers for 24 years (1933–1953) during FDR's era. |

| Political Parties Involved | Both Democrats and Republicans have achieved unified control. |

| Impact on Legislation | Easier passage of bills aligned with the party's agenda. |

| Current Status (as of 2023) | Republicans control the House, Democrats control the Senate (divided govt). |

| Historical Significance | Often tied to major legislative achievements or shifts in policy. |

| Duration of Control | Varies; can last from a few years to over a decade. |

| Key Factors for Control | Electoral success, redistricting, and voter turnout. |

Explore related products

$10.41 $19.99

$13.99 $31.99

$20.46 $36

What You'll Learn

Historical instances of unified party control in Congress

Unified control of Congress by a single political party has occurred numerous times throughout U.S. history, often shaping legislative agendas and policy outcomes. One notable example is the Democratic Party’s dominance during Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency in the 1930s and 1940s. From 1933 to 1947, Democrats held majorities in both the House and Senate, enabling the passage of transformative New Deal and wartime legislation. This era exemplifies how unified control can facilitate rapid and sweeping policy changes, particularly during crises. However, such dominance also raises questions about checks and balances, as opposition voices may be marginalized.

Another significant period of unified control occurred under the Republican Party during the early 20th century. From 1921 to 1931, Republicans controlled both chambers of Congress, coinciding with the presidencies of Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover. This period saw the implementation of pro-business policies, tax cuts, and reduced government intervention, reflecting the party’s conservative economic agenda. Yet, the Great Depression exposed vulnerabilities in these policies, leading to a shift in political power. This instance underscores how unified control can both advance a party’s vision and leave it accountable for subsequent outcomes.

In more recent history, the Democratic Party regained unified control of Congress during the early years of Barack Obama’s presidency (2009–2011). This brief window allowed for the passage of landmark legislation, including the Affordable Care Act and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. However, the 2010 midterm elections shifted the House to Republican control, illustrating the transient nature of unified control in modern politics. This example highlights the importance of timing and public sentiment in sustaining legislative momentum.

Comparatively, the Republican Party achieved unified control under President Donald Trump in 2017, holding both chambers until Democrats regained the House in 2019. During this period, significant tax reform and judicial appointments were prioritized, reflecting the party’s conservative agenda. However, legislative gridlock on issues like healthcare and immigration demonstrated the limitations of unified control in a deeply polarized political environment. This case study reveals that even with majorities in both chambers, internal party divisions and external opposition can hinder progress.

Analyzing these historical instances, a recurring theme emerges: unified control of Congress amplifies a party’s ability to enact its agenda but does not guarantee long-term success or public approval. Practical takeaways include the importance of strategic timing, coalition-building, and responsiveness to public needs. For policymakers, understanding these dynamics can inform efforts to maximize legislative impact during periods of unified control. For citizens, recognizing the historical context of such instances fosters a more nuanced understanding of congressional power and its limitations.

Dwight Eisenhower's Political Party: Unraveling the Republican Affiliation

You may want to see also

Impact of unified control on legislative productivity

Unified control of both the Senate and the House by a single political party has historically been a double-edged sword for legislative productivity. On one hand, it streamlines the passage of bills by eliminating partisan gridlock, as seen during the early years of the Obama administration when Democrats controlled both chambers and passed the Affordable Care Act. On the other hand, unified control can lead to overreach, as evidenced by the backlash against the same administration’s stimulus package, which critics argued was bloated and inefficient. The key lies in balancing efficiency with accountability—a delicate task that often hinges on the party’s internal cohesion and its ability to manage ideological factions.

Consider the legislative output during periods of unified control. Between 2003 and 2007, Republicans controlled both chambers and the presidency, resulting in the passage of significant legislation like the Patriot Act and Medicare Part D. However, productivity waned as the party struggled to address long-term issues like Social Security reform, highlighting the limitations of unified control when faced with complex, divisive policies. Conversely, the 110th Congress (2007–2009), under Democratic control, passed over 400 bills, though many were symbolic or minor, underscoring the challenge of translating majority power into meaningful, impactful legislation.

To maximize productivity under unified control, parties must adopt a strategic approach. First, prioritize a clear, focused agenda. For instance, the Contract with America in 1994, championed by Republicans, provided a roadmap for legislative action, resulting in the passage of welfare reform and balanced budget legislation. Second, engage in bipartisan outreach where possible. Even with a majority, incorporating input from the opposition can lend legitimacy to bills and reduce future resistance, as seen in the bipartisan support for the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990. Finally, manage internal dissent effectively. A unified party in name only can stall progress, as demonstrated by the Tea Party faction’s resistance to Republican leadership during the Obama era.

Practical tips for policymakers include setting measurable goals, such as targeting a specific number of bills per session or focusing on high-impact areas like infrastructure or healthcare. Additionally, leverage technology to track legislative progress and ensure transparency, fostering public trust and accountability. For example, the use of online platforms to publish bill statuses and committee hearings can keep constituents informed and engaged. By combining strategic planning with tactical execution, unified control can be a catalyst for legislative productivity rather than a recipe for stagnation.

In conclusion, the impact of unified control on legislative productivity is neither inherently positive nor negative—it depends on how the majority party wields its power. History shows that success requires a blend of vision, discipline, and adaptability. Parties must avoid the pitfalls of overreach while capitalizing on the opportunity to enact meaningful change. By studying past examples and adopting best practices, policymakers can turn unified control into a tool for effective governance, ensuring that legislative productivity aligns with the public’s needs and expectations.

Understanding Political Territory: Boundaries, Power, and Sovereignty Explained

You may want to see also

Role of midterm elections in shifting majorities

Midterm elections, occurring halfway through a president's term, often serve as a referendum on the incumbent administration. Historically, they have been a mechanism for voters to express dissatisfaction or support for the party in power, frequently resulting in a shift of majorities in Congress. For instance, in 2010, the Republican Party gained 63 seats in the House of Representatives during President Obama’s midterm, a stark rebuke of his policies and a clear example of how midterms can realign legislative control. This phenomenon underscores the cyclical nature of American politics, where power oscillates in response to public sentiment and governance performance.

Analyzing the mechanics of midterm shifts reveals a pattern: the president’s party typically loses seats in Congress. Since the Civil War, the president’s party has averaged a loss of 30 House seats and four Senate seats in midterms. This trend is driven by factors such as voter fatigue, economic conditions, and the absence of a presidential candidate to galvanize the base. For example, in 1994, Republicans seized control of both the House and Senate during Bill Clinton’s midterm, a shift attributed to backlash against his healthcare reform efforts. Such outcomes highlight the midterm’s role as a corrective tool, allowing voters to balance power when one party dominates both branches.

To understand the practical implications, consider the legislative gridlock or momentum that follows a midterm shift. When the opposition party gains a majority, it can block the president’s agenda, as seen in 2018 when Democrats regained the House, stymieing many of Trump’s initiatives. Conversely, a unified Congress post-midterm can accelerate policy implementation, as in 2002 when Republicans expanded their majority under George W. Bush, enabling swift action on tax cuts and homeland security. These scenarios illustrate how midterms act as a pivot point, reshaping the political landscape and influencing governance for the remainder of the presidential term.

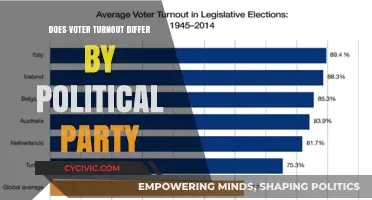

For voters and strategists alike, midterms demand a tactical approach. Campaigns must focus on local issues and voter turnout, as midterms historically suffer from lower participation rates compared to presidential elections. Practical tips include leveraging grassroots mobilization, targeting swing districts, and framing the election as a check on power rather than a presidential endorsement. By understanding the midterm’s unique dynamics, parties can position themselves to capitalize on the electorate’s desire for balance, ensuring their role in shifting majorities and shaping policy direction.

Top Universities for Political Psychology: A Comprehensive Guide to Studying

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Presidential influence during unified party control

Unified party control of Congress—when one party holds majorities in both the Senate and the House of Representatives—amplifies presidential influence in distinct ways. During these periods, presidents can more effectively advance their legislative agendas, as their party’s control of both chambers reduces the likelihood of gridlock. For example, President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs in the 1960s, enacted during Democratic control of Congress, illustrate how unified government can lead to sweeping policy changes. This alignment allows presidents to prioritize their initiatives without the constant need for bipartisan compromise, streamlining the legislative process.

However, unified control does not guarantee presidential success. The president’s ability to influence Congress depends on their leadership style, party cohesion, and the specifics of their agenda. For instance, while President Barack Obama benefited from Democratic majorities in his first two years, passing the Affordable Care Act, he faced challenges maintaining party unity on other issues. Conversely, President Donald Trump, despite Republican control of Congress, struggled to achieve major legislative victories beyond the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017. This highlights that unified control is a tool, not a guarantee, and its effectiveness hinges on strategic use.

Presidents must also navigate intraparty divisions during unified control. Even within the same party, ideological differences can stall progress. For example, during President Bill Clinton’s tenure, Democratic control of Congress did not prevent clashes with more progressive or conservative factions within his party. To maximize influence, presidents must actively manage these dynamics, using tools like the bully pulpit, executive orders, and targeted negotiations to align their party’s priorities. Practical tips include prioritizing issues with broad party support and leveraging committee chairs and leadership to shepherd bills through Congress.

The duration of unified control further shapes presidential influence. Historically, such periods are often short-lived, as midterm elections frequently shift the balance of power. Presidents must act decisively within this window, focusing on high-impact legislation that can be passed quickly. For instance, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first 100 days, during Democratic control, saw the passage of numerous New Deal programs. A step-by-step approach for presidents includes: (1) identifying key priorities, (2) building consensus within the party, and (3) using procedural tools like budget reconciliation to expedite passage. Cautions include avoiding overreach, as public backlash can erode support, and maintaining flexibility to adapt to unforeseen challenges.

In conclusion, unified party control of Congress provides presidents with a unique opportunity to shape policy, but its effectiveness depends on strategic leadership and party management. By understanding historical examples, navigating intraparty dynamics, and acting swiftly, presidents can maximize their influence during these rare periods of alignment. The takeaway is clear: unified control is a powerful but perishable asset, and its successful use requires both vision and tactical precision.

Who is Garland? Unveiling the Political Figure's Role and Influence

You may want to see also

Partisan polarization effects on unified government outcomes

In the United States, unified government—when one party controls the presidency and both chambers of Congress—has historically been a double-edged sword. Since 1945, unified control has occurred in 26 of 78 years, yet its effectiveness in passing legislation has increasingly been undermined by partisan polarization. Polarization, measured by the ideological gap between parties, has widened dramatically since the 1970s, with DW-NOMINATE scores showing Democratic and Republican members now farther apart than ever. This ideological divergence transforms unified government from a mechanism for efficiency into a battleground for extreme agendas, often alienating moderates and exacerbating public distrust.

Consider the 2003-2007 Republican trifecta under George W. Bush. While successful in passing tax cuts and the Patriot Act, the era also saw divisive policies like the Iraq War authorization, which polarized public opinion and eroded bipartisan cooperation. Similarly, the 2021 Democratic trifecta under Joe Biden faced internal party fractures, with progressives and moderates clashing over the scope of infrastructure and social spending bills. Polarization forces unified governments to prioritize party purity over pragmatic compromise, limiting their ability to address complex, cross-partisan issues like healthcare or climate change.

To mitigate polarization’s impact, unified governments must adopt strategic legislative tactics. First, focus on incremental policies with broad appeal, such as targeted tax credits or disaster relief, rather than sweeping reforms. Second, leverage procedural tools like budget reconciliation to bypass filibusters, though this risks further entrenching partisan divisions. Third, engage in symbolic bipartisan gestures, such as appointing opposition members to advisory roles, to signal cooperation without sacrificing core goals. These steps, while not foolproof, can temper polarization’s effects and preserve unified government’s legitimacy.

A cautionary tale emerges from the 1994 Republican Revolution, where Newt Gingrich’s aggressive agenda under a unified GOP government led to a government shutdown and public backlash. Polarization amplifies the risks of overreach, as parties mistake electoral mandates for ideological carte blanche. Unified governments must balance ambition with restraint, recognizing that public support is fragile and easily eroded by perceived extremism. Practical advice for policymakers: conduct regular cross-party town halls, commission non-partisan policy analyses, and prioritize issues with bipartisan polling support to sustain momentum.

Ultimately, partisan polarization transforms unified government from a tool for decisive action into a high-wire act of ideological balancing. While unified control remains a potent force in American politics, its outcomes are increasingly dictated by the degree of polarization rather than the strength of the majority. Policymakers must adapt by embracing pragmatism, transparency, and strategic bipartisanship to navigate this polarized landscape effectively. Without such adjustments, unified government risks becoming a recipe for gridlock, not progress.

Is the League of Nations a Political Party? Exploring Its Role

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, it is common for one political party to control both chambers of Congress. Historically, the same party has held majorities in both the Senate and the House of Representatives during various periods.

As of the most recent data (October 2023), the Democratic Party controlled both the Senate and the House during the 117th Congress (2021–2023).

It varies by era, but since the mid-20th century, one party has controlled both chambers for roughly 60% of the time. This is influenced by factors like presidential elections, midterm shifts, and redistricting.

When one party controls both chambers, it can more easily pass legislation aligned with its agenda, confirm presidential appointments, and shape the federal budget. However, it still requires cooperation with the president to enact laws.

No, third parties have never controlled both the Senate and the House. The two-party system dominated by Democrats and Republicans has consistently held majorities in Congress since the mid-19th century.