The question of whether two dominant political parties constantly butting heads cripples democracy is a pressing concern in many modern political systems. While a two-party system can foster clear ideological distinctions and simplify voter choices, it often devolves into polarization, gridlock, and hyper-partisanship. This dynamic can undermine democratic principles by stifling compromise, sidelining minority voices, and prioritizing party interests over the common good. As legislative progress grinds to a halt and public trust erodes, the very foundation of democracy—effective governance and representation—is threatened, raising critical questions about the sustainability of such a system in fostering a healthy, functioning democracy.

Explore related products

$11.99 $16.95

$39.99 $44.99

What You'll Learn

Polarization's Impact on Policy-Making

Polarization transforms policy-making from a deliberative process into a zero-sum game, where compromise is equated with defeat. In the U.S. Congress, for instance, the number of filibusters has skyrocketed since the 1970s, from fewer than 10 per session to over 100 in recent years. This procedural tool, once a rarity, now routinely stalls legislation, even on issues with broad public support, such as gun control or climate change. When every policy becomes a battleground for ideological supremacy, the machinery of governance grinds to a halt, leaving urgent problems unaddressed.

Consider the 2013 government shutdown, triggered by partisan disputes over the Affordable Care Act. For 16 days, non-essential federal services ceased, costing the economy an estimated $24 billion. This example illustrates how polarization prioritizes party loyalty over public welfare. Policymakers, fearful of alienating their base, often reject bipartisan solutions, even when those solutions are more effective. A 2021 Pew Research study found that 60% of Americans believe their representatives are more focused on party interests than the nation’s needs, a sentiment that erodes trust in democratic institutions.

To mitigate polarization’s impact, policymakers can adopt structured mechanisms for collaboration. One practical strategy is the creation of bipartisan task forces, as seen in the 2018 passage of the First Step Act, which reformed federal sentencing laws. By isolating specific issues from broader ideological battles, such task forces foster targeted problem-solving. Another approach is to incentivize bipartisanship through legislative rules, such as requiring a supermajority for certain bills, which encourages cross-party negotiation. However, these solutions require political will, a resource often in short supply in polarized environments.

A cautionary tale emerges from countries like Belgium, which endured a 541-day period without a government in 2010-2011 due to linguistic and regional divisions. While Belgium’s case is extreme, it underscores the fragility of governance in polarized systems. For democracies to function, policymakers must balance advocacy with adaptability, recognizing that policy-making is not a winner-takes-all contest but a collaborative endeavor. Without this shift, polarization will continue to cripple democracy, leaving societies vulnerable to stagnation and crisis.

Understanding Voter Demographics: Who Participates in Political Elections and Why

You may want to see also

Gridlock in Legislative Processes

In the United States, legislative gridlock has become a defining feature of the political landscape, with the two-party system often exacerbating this phenomenon. When Democrats and Republicans prioritize partisan interests over compromise, the result is a paralyzed government, unable to pass meaningful legislation. Consider the 2013 federal government shutdown, which lasted 16 days and cost the economy an estimated $24 billion. This example illustrates how gridlock can have tangible, detrimental effects on the nation's well-being.

To understand the mechanics of gridlock, let's examine the legislative process. A bill must pass through multiple stages, including committee review, floor debate, and conference committee negotiations, before reaching the president's desk. At each stage, partisan disagreements can derail progress. For instance, in the Senate, the filibuster rule allows a single senator to delay a vote on a bill indefinitely, effectively killing it. This tactic has been used increasingly in recent years, with the number of filibusters rising from 8 in the 1980s to over 130 in the 2010s. To mitigate this, some propose reforming Senate rules, such as implementing a "talking filibuster," which would require senators to actively debate on the floor, making it more difficult to obstruct legislation.

A comparative analysis of other democracies reveals alternative approaches to legislative decision-making. In parliamentary systems like the United Kingdom, the majority party wields significant power, enabling swift passage of legislation. However, this model can also lead to a lack of minority representation. Mixed-member proportional systems, as seen in Germany, allocate seats based on party vote share, fostering coalition-building and compromise. These examples suggest that the US two-party system, while promoting stability, may inadvertently encourage gridlock. One potential solution is to adopt elements of proportional representation, which could incentivize parties to work together and reduce the prevalence of all-or-nothing politics.

Persuading lawmakers to prioritize compromise over partisan victory is crucial to breaking the gridlock cycle. This requires a shift in incentives, rewarding politicians for collaboration rather than obstruction. Citizens can play a role by holding their representatives accountable, demanding they work across the aisle to address pressing issues. Additionally, implementing term limits or campaign finance reforms could reduce the influence of special interests and encourage a more cooperative legislative environment. By taking these steps, we can begin to untangle the gridlock that has crippled legislative processes and restore faith in democratic institutions.

Descriptive accounts of gridlock often overlook the human cost of legislative inaction. Consider the millions of Americans affected by the failure to pass comprehensive immigration reform, or the lack of progress on climate change legislation. These issues demand urgent attention, yet partisan bickering continues to stall progress. To address this, lawmakers must engage in a structured, goal-oriented dialogue, focusing on shared objectives rather than ideological differences. This could involve creating bipartisan task forces or utilizing consensus-building techniques, such as deliberative polling or citizen juries, to inform policy decisions. By adopting these practices, legislators can transcend partisan divides and work towards a more functional, responsive democracy.

What's on Politics: Latest Debates, Policies, and Global Developments

You may want to see also

Voter Disengagement and Apathy

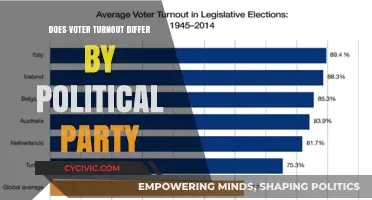

To combat this, democracies must adopt practical measures that re-engage voters. First, implement ranked-choice voting to give citizens more nuanced options beyond the binary party system. Second, reduce the influence of money in politics by capping campaign contributions and mandating public financing. Third, invest in civic education programs targeting younger demographics—studies show that voters aged 18–29 are 30% less likely to vote than those over 65. A pilot program in Sweden, for instance, integrated political literacy into high school curricula, resulting in a 15% increase in youth voter turnout within three years. These steps aren’t just theoretical—they’re actionable solutions to break the cycle of apathy.

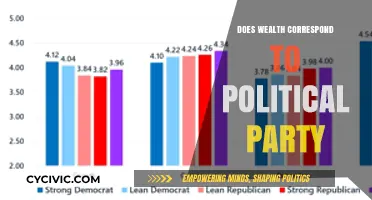

A comparative analysis reveals that multiparty systems often fare better in maintaining voter engagement. In Germany, where coalition governments are the norm, voter turnout averages 76%, compared to 57% in the U.S. The key difference? Citizens perceive their votes as impactful because no single party dominates, forcing collaboration. Contrast this with the U.S., where the two-party system often reduces complex issues to polarizing slogans. For example, the 2016 Brexit referendum in the U.K. saw a 72% turnout, but the binary nature of the question left many feeling alienated post-vote, highlighting the dangers of oversimplification in divisive political landscapes.

Persuasively, it’s clear that voter apathy isn’t just a personal choice—it’s a systemic failure. When parties prioritize obstruction over progress, democracy suffers. Take the U.S. Congress, where partisan filibusters have stalled critical legislation like the For the People Act, aimed at expanding voting rights. This isn’t just frustrating; it’s demobilizing. Voters need to see their representatives as problem-solvers, not combatants. A 2021 Pew Research study found that 64% of Americans believe political leaders are more focused on winning arguments than improving the country. To reverse this trend, parties must commit to bipartisan solutions, even if it means compromising on ideological purity. Democracy thrives on participation, and participation requires hope—hope that voting isn’t just an exercise in futility.

Fidelity's Political Affiliations: Uncovering Their Supported Parties and Candidates

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Media's Role in Party Conflict

To counteract this, media organizations must adopt a three-step approach: fact-checking, balanced representation, and contextual reporting. Fact-checking should be rigorous and transparent, with dedicated teams verifying claims in real-time. Balanced representation involves inviting diverse voices to debates, ensuring that minority perspectives are not drowned out by dominant narratives. Contextual reporting requires journalists to provide historical and global context, helping audiences understand the broader implications of party conflicts. For example, the BBC’s "Reality Check" segments during Brexit debates offered viewers a factual counterpoint to hyperbolic political statements, demonstrating how media can act as a stabilizing force.

However, the media’s ability to de-escalate party conflict is hindered by its reliance on advertising revenue, which often rewards divisive content. A 2021 report by the Reuters Institute revealed that articles with polarizing headlines generate 38% more clicks than neutral ones. This economic incentive creates a vicious cycle: media outlets prioritize conflict-driven narratives, which in turn fuel partisan animosity. To break this cycle, policymakers could explore funding models that reward public service journalism, such as government grants or tax incentives for non-profit news organizations. Additionally, audiences can take proactive steps by diversifying their news sources and supporting independent media platforms.

Comparatively, countries with strong public broadcasting systems, like Germany and Japan, offer a blueprint for media’s constructive role in party conflict. These nations’ state-funded broadcasters are legally mandated to provide impartial coverage, reducing the influence of commercial pressures. For instance, Germany’s ARD network employs a strict editorial code that requires equal airtime for all major parties during election campaigns. Such models highlight the importance of institutional safeguards in ensuring media acts as a mediator rather than a provocateur.

Ultimately, the media’s role in party conflict is not predetermined—it is shaped by choices made by journalists, executives, and consumers. By prioritizing accuracy over outrage, diversity over homogeneity, and context over clicks, the media can transform from a catalyst of division to a pillar of democratic discourse. Practical steps include subscribing to fact-based outlets, engaging in cross-partisan dialogue, and advocating for media literacy education in schools. The stakes are high, but the path forward is clear: a responsible media is essential to preventing party conflicts from crippling democracy.

Discovering Your Political Compass: A Guide to Personal Alignment

You may want to see also

Alternatives to Two-Party Systems

The dominance of two-party systems in many democracies often leads to polarization, gridlock, and a narrowing of political discourse. However, alternatives exist that can foster greater inclusivity, representation, and functionality. One such alternative is proportional representation (PR), a voting system where parties gain seats in proportion to their share of the vote. Countries like Germany and New Zealand use PR, allowing smaller parties to gain representation and reducing the winner-takes-all mentality of two-party systems. This encourages coalition-building and forces parties to collaborate, mitigating the adversarial dynamics that cripple governance.

Another viable alternative is ranked-choice voting (RCV), which allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference. If no candidate secures a majority, the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated, and their votes are redistributed to the remaining candidates. This system, used in cities like New York and countries like Australia, reduces the "spoiler effect" and encourages candidates to appeal to a broader electorate. By minimizing strategic voting and negative campaigning, RCV can create a more civil and representative political environment.

Multi-party systems, common in countries like India and Brazil, offer yet another alternative. These systems naturally accommodate diverse ideologies and regional interests, preventing the dominance of any single party. While they can lead to complex coalitions, they also ensure that a wider spectrum of voices is heard. For instance, India’s multi-party democracy has allowed regional parties to address local issues effectively, demonstrating that diversity in representation can strengthen democratic responsiveness.

Finally, deliberative democracy presents a paradigm shift by emphasizing citizen engagement and reasoned debate. Models like citizens’ assemblies, used in Ireland to address issues like abortion and climate change, involve randomly selected citizens in decision-making processes. This approach bypasses party politics altogether, focusing on informed, collaborative problem-solving. While not a replacement for electoral systems, deliberative democracy complements traditional structures by fostering trust and reducing partisan divides.

Implementing these alternatives requires careful consideration of cultural, historical, and institutional contexts. For instance, transitioning to PR may necessitate constitutional amendments, while RCV demands voter education to ensure understanding. However, the potential benefits—reduced polarization, greater representation, and more effective governance—make these alternatives worth exploring for democracies seeking to break free from the constraints of two-party systems.

Bipartisan Political Committees: Do Both Parties Collaborate in Governance?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, when two parties consistently prioritize partisan interests over governance, it can lead to gridlock, reduced policy effectiveness, and diminished public trust in democratic institutions.

It can, but only if both parties engage in constructive dialogue, compromise, and prioritize the common good over ideological rigidity.

Often, yes. Extreme polarization can alienate voters who feel their voices are ignored, leading to apathy or disengagement from the political process.

Third parties can introduce new ideas and reduce polarization, but structural barriers like winner-take-all systems often limit their impact in two-party-dominated democracies.

Yes, media that amplifies partisan divides can deepen polarization, making it harder for citizens to engage in informed, non-partisan discussions about critical issues.