The Electoral College system in the United States has long been a subject of debate, particularly regarding its role in shaping the country's political landscape. One of the most contentious questions is whether the Electoral College inherently encourages a two-party political system. Proponents argue that the winner-take-all method used in most states consolidates power within two dominant parties, as smaller parties struggle to secure enough electoral votes to remain viable. Critics, however, contend that the system stifles political diversity by marginalizing third-party candidates and limiting voters' choices. This dynamic raises important questions about the balance between stability and representation in American democracy, as the Electoral College continues to influence the strategic calculations of parties and candidates alike.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Winner-Takes-All System | 48 states use a winner-takes-all approach, awarding all electoral votes to the candidate who wins the popular vote in that state, favoring major parties. |

| Discouragement of Third Parties | Third-party candidates rarely win electoral votes due to the winner-takes-all system, limiting their viability. |

| Focus on Swing States | Campaigns concentrate on a handful of swing states, reinforcing the dominance of the two major parties. |

| Strategic Candidate Selection | Parties nominate candidates with broad appeal to maximize electoral college success, often excluding niche or third-party candidates. |

| Suppression of Minority Voices | Smaller parties and independent candidates struggle to gain traction, as the system prioritizes majority rule. |

| Historical Two-Party Dominance | Since the 1850s, the U.S. has had a two-party system, reinforced by the electoral college structure. |

| Lack of Proportional Representation | Electoral votes are not allocated proportionally, further marginalizing third parties. |

| High Barriers to Entry | Third-party candidates face significant challenges in securing ballot access and funding due to the electoral college system. |

| Reinforcement of Polarization | The system encourages extreme positions to appeal to the party base, exacerbating political polarization. |

| Limited Incentive for Coalition Building | Parties focus on solidifying their base rather than building broad coalitions, as the electoral college rewards majority wins. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Historical origins of the Electoral College and its impact on party formation

- Strategic incentives for candidates to focus on swing states only

- Suppression of third-party viability due to winner-take-all systems

- Role of the Electoral College in polarizing political discourse

- Comparison of two-party dominance in Electoral College vs. proportional systems

Historical origins of the Electoral College and its impact on party formation

The Electoral College, established by the Founding Fathers during the Constitutional Convention of 1787, was a compromise between those who favored direct popular election of the president and those who preferred congressional selection. Its origins are deeply rooted in the political and social context of the late 18th century. At the time, the United States was a loosely connected group of states with varying interests, and the Founders sought a system that would balance state and federal power while ensuring stability. The Electoral College was designed to provide a mechanism for presidential selection that would reflect both the will of the people and the interests of the states. Each state was allocated a number of electors equal to its total representation in Congress (Senate and House combined), giving smaller states a proportionally larger voice in the process.

The structure of the Electoral College inadvertently laid the groundwork for the emergence of a two-party system. In the early years of the republic, political factions began to coalesce around key figures and ideologies. The first presidential election in 1789, won by George Washington, was uncontested, but by the 1790s, the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans emerged as the dominant parties. The winner-take-all method of allocating electors, adopted by most states, incentivized parties to build broad coalitions to secure a majority of electoral votes. This system rewarded parties that could appeal to a wide range of voters across different states, effectively marginalizing smaller, regional, or ideologically narrow factions. The Electoral College thus encouraged the consolidation of political interests into two major parties capable of competing on a national scale.

The impact of the Electoral College on party formation became more pronounced in the 19th century. The rise of the Second Party System, dominated by the Democrats and Whigs, further entrenched the two-party dynamic. The Electoral College's emphasis on state-level majorities pushed parties to organize and campaign strategically, focusing on swing states and key demographic groups. This focus on winning states rather than a nationwide popular vote reinforced the importance of building a broad-based party structure. By the mid-19th century, the Republican Party emerged as a major force, replacing the Whigs and solidifying the two-party system that persists to this day. The Electoral College's design ensured that only parties with national appeal and organizational capacity could effectively compete for the presidency.

Critics argue that the Electoral College's historical impact on party formation has limited political diversity by favoring two dominant parties. Smaller parties, such as the Libertarians or Greens, face significant barriers to gaining traction in the Electoral College system. The winner-take-all approach in most states discourages voters from supporting third-party candidates, as their votes are unlikely to translate into electoral votes. This dynamic perpetuates the two-party system by making it difficult for alternative voices to gain a foothold. Despite occasional challenges, such as the 1992 candidacy of Ross Perot, the Electoral College has consistently reinforced the dominance of the Democratic and Republican Parties.

In conclusion, the historical origins of the Electoral College were shaped by the Founders' desire to create a stable and balanced system of presidential selection. Its design, particularly the state-based allocation of electors and the winner-take-all method, has had a profound impact on the formation and persistence of a two-party system in the United States. By incentivizing broad-based coalitions and national organization, the Electoral College has effectively marginalized smaller parties and solidified the dominance of the Democrats and Republicans. While this system has ensured political stability, it has also limited the diversity of political representation, raising questions about its long-term implications for American democracy.

Are Political Parties Truly Committed to Meaningful Reform?

You may want to see also

Strategic incentives for candidates to focus on swing states only

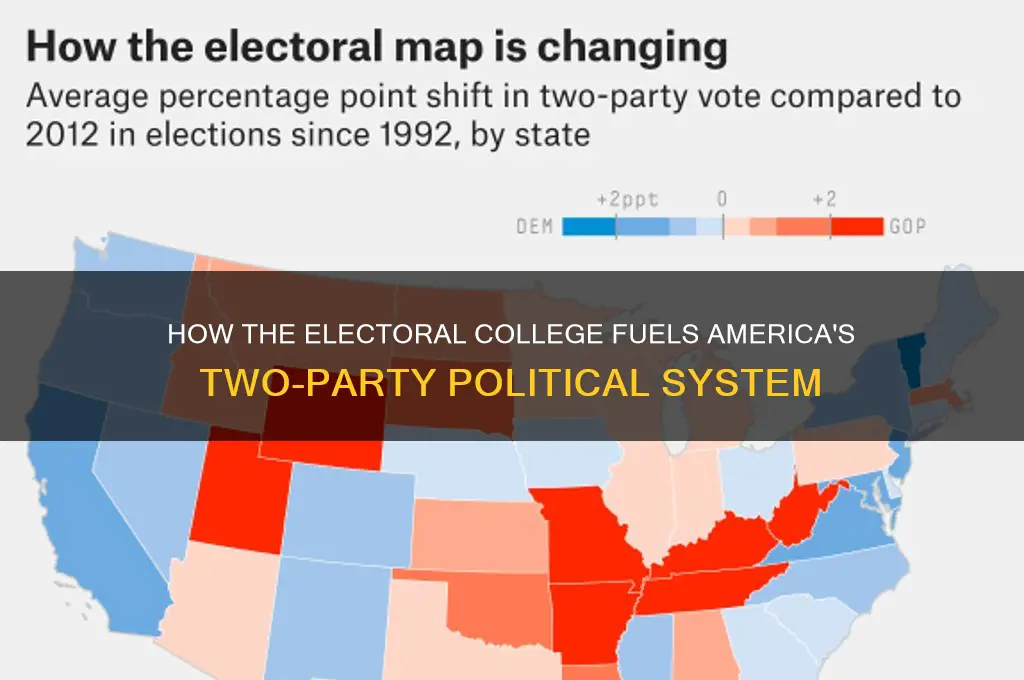

The Electoral College system in the United States creates strategic incentives for presidential candidates to focus disproportionately on a handful of swing states, rather than campaigning nationally. This is primarily because the Electoral College allocates each state's electoral votes on a winner-take--all basis (except in Maine and Nebraska), meaning candidates have a strong incentive to target states where the outcome is uncertain. Swing states, such as Florida, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, are where the margins between the two major parties are narrowest, making them critical battlegrounds for securing the 270 electoral votes needed to win the presidency. By concentrating resources—time, money, and campaign events—on these states, candidates maximize their chances of tipping the electoral balance in their favor.

One strategic incentive for this focus is the efficiency of resource allocation. Campaigning in solidly red or blue states offers little return on investment, as the outcome in those states is largely predictable. For example, a Republican candidate is unlikely to win California, a reliably Democratic state, and vice versa for a Democrat in Texas. In contrast, swing states are where small shifts in voter sentiment can yield significant electoral gains. Candidates can tailor their messages to address local issues and demographics in these states, increasing their likelihood of success. This targeted approach allows campaigns to stretch their limited resources further, making it a rational strategy under the Electoral College system.

Another incentive is the mathematical reality of the Electoral College. Since the system is zero-sum—winning a state by one vote secures the same number of electoral votes as winning by a landslide—candidates have little reason to expand their efforts beyond the states that will deliver the necessary electoral votes. For instance, in 2020, both major party candidates focused heavily on states like Arizona, Georgia, and Michigan, where the electoral votes were up for grabs, rather than spending time in non-competitive states. This narrow focus is a direct result of the winner-take-all mechanism, which encourages candidates to prioritize states where their efforts can make a decisive difference.

Additionally, the media and fundraising dynamics reinforce this strategy. Swing states receive disproportionate media coverage, as they are seen as the key determinants of the election outcome. Candidates who campaign in these states gain more visibility and can leverage this attention to boost fundraising efforts. Donors are more likely to contribute to campaigns that appear competitive and strategically focused, further incentivizing candidates to concentrate on swing states. This feedback loop between media attention, fundraising, and campaign strategy solidifies the focus on battlegrounds.

Finally, the Electoral College system discourages candidates from broadening their appeal to a national audience. Since the popular vote does not determine the winner, candidates have little incentive to campaign in states where they have no chance of winning or in deeply red or blue states where their efforts would not change the outcome. This narrow focus can exacerbate regional divisions and limit the diversity of issues addressed during the campaign. As a result, the Electoral College not only encourages a two-party system but also reinforces a campaign strategy that prioritizes swing states at the expense of a more inclusive, national approach.

How Political Parties Decide to Endorse Candidates: A Comprehensive Guide

You may want to see also

Suppression of third-party viability due to winner-take-all systems

The Electoral College system in the United States, particularly its widespread use of winner-take-all mechanisms, significantly suppresses the viability of third parties. In 48 states and Washington D.C., the winner-take-all rule awards all of a state's electoral votes to the candidate who wins the popular vote in that state, regardless of the margin of victory. This system creates a high barrier for third-party candidates, as it incentivizes voters to support only those candidates who have a realistic chance of winning a plurality. Voters are often reluctant to "waste" their votes on third-party candidates who are unlikely to secure any electoral votes, a phenomenon known as strategic or tactical voting.

The winner-take-all system effectively marginalizes third parties by making it nearly impossible for them to gain a foothold in the electoral process. Since third-party candidates rarely win a plurality in any state, they are systematically shut out of the Electoral College. This exclusion perpetuates a cycle where third parties struggle to raise funds, attract media attention, or build a national presence, further diminishing their chances of success. As a result, the political landscape remains dominated by the two major parties, which are seen as the only viable options for securing electoral votes and ultimately winning the presidency.

Moreover, the winner-take-all system discourages third-party candidates from competing in states where they might have a strong base of support. Even if a third-party candidate has significant backing in a particular state, they must still secure a plurality to win any electoral votes. This all-or-nothing approach forces third parties to spread their limited resources across multiple states, diluting their impact and reducing their chances of success. In contrast, the two major parties can focus their efforts on swing states, further entrenching their dominance.

The suppression of third-party viability also stems from the psychological effect of the winner-take-all system on voters. The perception that only the Democratic and Republican candidates can win leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy, as voters are more likely to align with one of the two major parties to avoid "spoiling" the election. This dynamic is exacerbated by media coverage, which often focuses disproportionately on the two major candidates, further marginalizing third-party voices. As a result, third parties are often relegated to the fringes of political discourse, unable to break through the structural barriers imposed by the Electoral College.

In summary, the winner-take-all systems employed in most states under the Electoral College create a hostile environment for third-party candidates. By awarding all electoral votes to the plurality winner, this mechanism discourages voters from supporting third parties, limits their ability to compete effectively, and perpetuates the dominance of the two major parties. Until significant reforms are made to the Electoral College, such as adopting proportional allocation of electoral votes or implementing ranked-choice voting, third parties will continue to face insurmountable obstacles in challenging the two-party system.

Do Independents Despise Both Parties? Unraveling Political Neutrality

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Role of the Electoral College in polarizing political discourse

The Electoral College, a cornerstone of the U.S. presidential election system, plays a significant role in shaping the country's political landscape, particularly in fostering a two-party dominance. This system, where electors from each state cast votes to determine the president, inherently encourages a winner-take-all approach in most states, marginalizing smaller parties and independent candidates. As a result, the political discourse becomes increasingly polarized, with the focus narrowing to the two major parties: the Democrats and the Republicans. This polarization is not merely a byproduct of the Electoral College but is deeply intertwined with its mechanics, which favor a binary political system.

One of the primary ways the Electoral College contributes to polarization is by incentivizing candidates to concentrate their campaigns on a handful of swing states. Since most states allocate all their electoral votes to the candidate who wins the popular vote within that state, candidates have little incentive to campaign in solidly red or blue states. This strategy effectively ignores large portions of the electorate, leading to a political discourse that caters primarily to the interests and concerns of voters in these swing states. Consequently, issues that resonate in swing states dominate the national conversation, while those pertinent to other regions are often sidelined. This narrow focus exacerbates divisions, as voters in non-swing states may feel their voices are not being heard, fostering resentment and further entrenching partisan loyalties.

Moreover, the Electoral College system discourages the emergence of third parties, which could potentially serve as a moderating force in political discourse. Third-party candidates face an uphill battle in securing electoral votes due to the winner-take-all structure, making it nearly impossible for them to gain a foothold in the political system. This lack of viable alternatives reinforces the two-party system, leaving voters with limited choices that often align with the extremes of the political spectrum. As a result, the middle ground is frequently overlooked, and the political dialogue becomes more confrontational, with each party striving to outdo the other in appealing to its base rather than seeking common ground.

The Electoral College also amplifies the impact of gerrymandering and strategic voter suppression efforts, which are often employed to solidify the dominance of one party over another in key states. These tactics further polarize the electorate by undermining the principle of fair representation. When voters perceive that the system is rigged against them, it deepens their distrust in the political process and strengthens their allegiance to their party, viewing it as the only means to counteract the opposition. This us-versus-them mentality is a direct consequence of the Electoral College's structure, which prioritizes state-level victories over national popular support.

In addition, the Electoral College's role in occasionally electing candidates who lose the popular vote adds another layer of polarization. Such outcomes can lead to widespread disillusionment among voters who feel their votes do not count, particularly in states where their preferred candidate wins the popular vote but loses the electoral vote. This discrepancy fuels narratives of electoral injustice and further divides the electorate along partisan lines. The perception that the system is inherently biased toward one party or the other erodes trust in democratic institutions, making constructive political discourse increasingly difficult.

In conclusion, the Electoral College significantly contributes to the polarization of political discourse in the United States by reinforcing a two-party system, marginalizing third parties, focusing campaigns on swing states, and exacerbating perceptions of electoral unfairness. While it was designed to balance state and federal interests, its current implementation fosters an environment where extreme positions are amplified, and moderate voices are drowned out. Addressing the polarizing effects of the Electoral College requires a critical reevaluation of its role in modern American democracy, potentially through reforms that promote greater inclusivity and representation.

Political Parties and Communal Riots: Unraveling Their Complex Role

You may want to see also

Comparison of two-party dominance in Electoral College vs. proportional systems

The Electoral College system in the United States, as opposed to proportional representation systems used in many other democracies, significantly encourages two-party dominance. In the U.S., the winner-takes-all method (employed by most states) awards all electoral votes to the candidate who wins the popular vote in that state, regardless of the margin of victory. This creates a strong incentive for voters to rally behind one of the two major parties, as voting for a third-party candidate is often seen as "wasting" a vote. The structure inherently disadvantages smaller parties, as they struggle to gain a foothold in a system where only the top two contenders have a realistic chance of securing electoral votes.

In contrast, proportional representation systems, such as those used in many European countries, allocate legislative seats in proportion to the percentage of the popular vote each party receives. This system naturally fosters multi-party politics because even smaller parties can secure representation if they garner a sufficient share of the vote. For example, in a proportional system, a party with 10% of the national vote would win roughly 10% of the seats, giving them a voice in governance. This encourages a broader spectrum of political ideologies and reduces the pressure on voters to strategically align with one of two dominant parties.

The Electoral College’s emphasis on winning states rather than the national popular vote further reinforces two-party dominance. Candidates focus their campaigns on swing states, where the outcome is uncertain, while largely ignoring solidly red or blue states. This strategy benefits the two major parties, which have the resources and infrastructure to compete in these critical battlegrounds. Smaller parties, lacking comparable resources, find it nearly impossible to break through this barrier, perpetuating the two-party system.

Proportional systems, on the other hand, encourage coalition-building and compromise, as no single party often wins a majority of seats. This dynamic can lead to more inclusive governance, as multiple parties must work together to form a government. In the U.S., the Electoral College’s winner-takes-all approach discourages such cooperation, as the focus is on securing a majority of electoral votes rather than building broad-based coalitions. This further entrenches the two-party system by minimizing the incentive for major parties to collaborate with smaller ones.

Finally, the psychological impact of the Electoral College on voters cannot be overlooked. The perception that only two parties have a chance of winning the presidency discourages support for third parties, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. In proportional systems, voters are more likely to support smaller parties knowing their vote contributes to representation, even if it doesn’t result in a majority government. This fundamental difference in voter behavior underscores why the Electoral College system is a driving force behind two-party dominance, while proportional systems naturally accommodate a more diverse political landscape.

Are Political Party Donations Tax Deductible? What You Need to Know

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the Electoral College encourages two-party politics because its winner-take-all method in most states makes it difficult for third parties to gain electoral votes, effectively marginalizing them.

The winner-take-all approach awards all of a state's electoral votes to the candidate who wins the popular vote in that state, making it hard for third parties to secure any electoral votes, thus reinforcing the dominance of the two major parties.

It is extremely difficult for third parties to succeed under the Electoral College system because they rarely win a majority of votes in any state, and the system does not proportionally allocate electoral votes.

Yes, the Electoral College discourages voters from supporting third-party candidates because many voters feel their vote would be "wasted" if it does not contribute to winning electoral votes in their state.

Yes, reforms such as proportional allocation of electoral votes or adopting the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact could reduce the two-party dominance by making it easier for third parties to gain representation and influence.