The U.S. Constitution does not explicitly address whether senators are authorized to make foreign trips, but it does outline the roles of the President and Congress in shaping foreign policy and engaging with foreign governments. The President is the sole organ of the nation in its external relations and the sole representative with foreign nations, according to Marshall. The President receives all foreign ambassadors and has the power to grant recognition to foreign governments, shaping foreign policy initiatives, and entering into discussions with foreign leaders. While the President does not make treaties, they can give them conditional approval subject to Senate approval. The Senate also plays a role in foreign affairs, as they must approve treaties and presidential appointments, and they can provide advice and consent on certain matters. The Constitution authorizes Congress to oversee but not establish U.S. foreign policy, except in cases of declaring war.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Who does the Constitution authorize to conduct foreign relations? | The Constitution allocates power over the conduct of foreign relations to the President and the executive branch. |

| Who does the Constitution authorize to negotiate treaties? | The President negotiates treaties with the advice and consent of the Senate. |

| Who does the Constitution authorize to receive and refuse ambassadors? | The President. |

| Can citizens apply to foreign governments for redress? | Yes, the Constitution does not prohibit this. |

| Can members of Congress travel overseas? | Yes, members of the House and Senate frequently travel overseas as part of congressional delegations ("CODELs") to meet with foreign officials. |

Explore related products

$15 $16.95

$4.65 $3.5

What You'll Learn

- The US Constitution gives the President the power to conduct foreign relations

- The Treaty Clause empowers the President to negotiate agreements with other countries

- The Senate must confirm treaties, but the President alone represents the nation

- Congress can legislate on matters preceding and following a presidential act

- Legislative diplomacy is frequent, but there are no reports on its extent

The US Constitution gives the President the power to conduct foreign relations

Many of the responsibilities for foreign affairs fell under the authority of the Executive branch, although important powers, such as treaty ratification, remained the responsibility of the legislative branch. The President makes treaties with the advice and consent of the Senate, but he alone negotiates. The Senate cannot intrude into the field of negotiation, and Congress itself is powerless to invade it.

The President is the sole mouthpiece of the nation in its dealings with other nations. As Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1790, "The transaction of business with foreign nations is executive altogether. It belongs, then, to the head of that department, except as to such portions of it as are specially submitted to the Senate."

The Supreme Court has held that the Executive retains exclusive authority over the recognition of foreign sovereigns and their territorial bounds. However, Congress may legislate on matters that precede and follow a presidential act of recognition, including in ways that may undercut the policies that inform the President's recognition decision.

The Logan Act is intended to prevent unauthorized American citizens from interfering in disputes or controversies between the United States and foreign governments. It states that any citizen of the United States who, without authority, carries on any correspondence or intercourse with any foreign government with the intent to influence the measures or conduct of any foreign government in relation to any disputes or controversies with the United States shall be fined or imprisoned or both.

The French Constitution of 1791: A Foundation for Democracy

You may want to see also

The Treaty Clause empowers the President to negotiate agreements with other countries

The US Constitution's Treaty Clause (Article II, Section 2, Clause 2) empowers the President to negotiate agreements with other countries. The Clause states that the President "shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur".

The Treaty Clause is an executive power that grants the President the authority to control diplomatic communications and negotiate international agreements without senatorial approval. This power is derived from the established international tradition of executives holding exclusive power over foreign relations and agreements. Leading Federalists like John Jay, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton supported this arrangement, particularly the level of agency given to the President relative to the Senate.

While the Senate has an "advice and consent" role, it is not a full partner with the President in the negotiation of treaties. The President alone has the power to speak or listen as a representative of the nation in external relations. The Senate cannot intrude into the field of negotiation, and Congress itself is powerless to invade it. The President's monopoly over foreign relations is further demonstrated by the power to "receive" ambassadors, including the right to refuse to receive them, request their recall, dismiss them, and determine their eligibility under US laws.

However, it is important to note that the President's authority to negotiate treaties is not absolute. Treaties become part of federal legislation and are considered the "'supreme Law of the Land'. Therefore, agreements beyond the President's competencies must have the approval of Congress (for congressional-executive agreements) or the Senate (for treaties). The Senate's approval is significant as treaties to which the United States is a party have the force of federal law. The Senate considers and approves a resolution of ratification, and if passed, ratification occurs through the formal exchange of instruments between the US and the foreign power(s).

CBD Legalization: Are THC Drug Tests Constitutional?

You may want to see also

The Senate must confirm treaties, but the President alone represents the nation

The US Constitution provides that the president "shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make Treaties, provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur" (Article II, section 2). Treaties are binding agreements between nations and become part of international law. Treaties to which the US is a party also have the force of federal legislation, forming part of what the Constitution calls "the supreme Law of the Land".

The Senate does not ratify treaties. Instead, it either approves or rejects a resolution of ratification. If the resolution passes, then ratification takes place when the instruments of ratification are formally exchanged between the US and the foreign power(s). The Senate has considered and approved for ratification all but a small number of treaties negotiated by the president and his representatives.

The Constitution's framers gave the Senate a share of the treaty-making power to give the president the benefit of the Senate's advice and counsel, to check presidential power, and to safeguard the sovereignty of the states by giving each state an equal vote in the treaty-making process. The Senate's authority is generally confined to approval or disapproval, with approval including the power to attach conditions or reservations to the treaty.

The authority to negotiate treaties has been assigned to the President alone as part of a general authority to control diplomatic communications. The President alone has the power to speak or listen as a representative of the nation. He makes treaties with the advice and consent of the Senate, but he alone negotiates. The Senate cannot intrude into the field of negotiation, and Congress itself is powerless to invade it.

While the Senate must confirm treaties, the President alone represents the nation.

Exploring the USS Constitution: A Visitor's Guide

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$13.59 $15.56

$24.49 $24.49

Congress can legislate on matters preceding and following a presidential act

While the Constitution allocates power over the conduct of foreign relations primarily to the executive, Congress can legislate on matters preceding and following a presidential act. The Legislative Branch, consisting of the House of Representatives and the Senate, has the sole authority to enact legislation and declare war, as well as the right to confirm or reject many presidential appointments. This includes the power to negotiate and approve treaties with foreign nations, which requires the advice and consent of a supermajority in the Senate.

The process of enacting legislation begins with the introduction of a bill to Congress. Anyone can write a bill, but only members of Congress can introduce it. These bills can propose public or private matters, with public bills being the most common. Once introduced, the bill is referred to the appropriate committee for review. There are numerous committees and subcommittees in both the Senate and the House that carefully examine and debate proposed legislation.

After the committee stage, the bill is voted on by both the Senate and the House. If the bill passes by a majority vote in both chambers, it is sent to the President for signature. At this point, the President may choose to veto the bill. However, Congress can override a presidential veto by achieving a two-thirds majority in favour of the bill in both chambers.

Congress has significant powers ascribed by the Constitution, including the authority to make and change laws. While the President can veto bills passed by Congress, Congress can override this veto under certain conditions. This back-and-forth process between Congress and the President underscores the dynamic nature of law-making, where both branches play a crucial role in shaping the nation's legislation.

In the specific context of foreign relations, Congress has historically engaged in legislative diplomacy, with members of the House and Senate frequently travelling overseas as part of congressional delegations (CODELs) to meet with foreign officials. This practice dates back to the First Congress in 1789 and continues to be a significant mode of engagement between the United States and the rest of the world. While the President is the sole representative of the nation in its external relations, Congress can and does play a role in shaping foreign policy through its legislative powers and diplomatic interactions.

Years Since March 9: Time Flies So Fast

You may want to see also

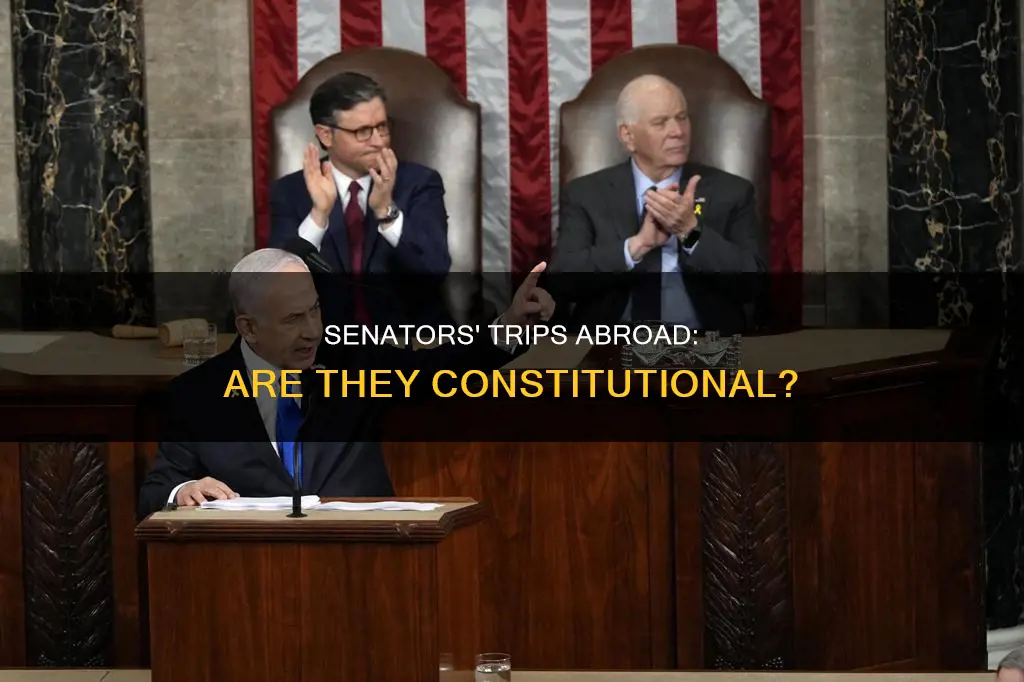

Legislative diplomacy is frequent, but there are no reports on its extent

While the Constitution allocates power over foreign relations primarily to the executive, diplomacy by Congress is common. Members of the House and Senate frequently travel overseas as part of congressional delegations or "CODELs" to meet with foreign officials. Foreign officials often make stops on Capitol Hill to discuss legislation, and visiting heads of state have issued formal addresses to Congress. These practices are not new; federal legislators and foreign officials have been communicating since the First Congress in 1789.

Despite the frequency of these trips, there are no complete reports on the nature and extent of these contacts. This lack of reporting is problematic as these contacts constitute a significant mode of engagement between the United States and other nations, impacting how US policy is perceived. This challenges the prevailing understanding that diplomacy is solely the executive branch's prerogative.

Theoretically, this gap between theory and practice could mean that Congress systematically violates the separation of powers, or that the understanding of executive power is incomplete or incorrect. The Logan Act, for example, was intended to prevent unauthorized American citizens from interfering in disputes between the US and foreign governments. However, attempts to invoke it against 47 Republican senators who wrote an open letter to Iran in 2015 were unsuccessful.

The lack of reporting on legislative diplomacy makes it difficult to assess the extent of these activities and whether they adhere to constitutional principles.

Hand Jobs: Sex or Not?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The Constitution does not explicitly authorize foreign trips by senators, but it also does not prohibit them. It allocates power over foreign relations primarily to the executive branch, but diplomacy by Congress is common.

The executive branch, led by the President, has the primary authority over foreign relations and the conduct of foreign policy, as outlined in Article II of the Constitution. The President is the sole representative and mouthpiece of the nation in its dealings with foreign nations.

Yes, members of Congress can and do engage in diplomacy. Members of the House and Senate frequently travel overseas as part of congressional delegations (CODELs) to meet with foreign officials. Foreign officials also make stops on Capitol Hill to discuss legislation.

Legislative diplomacy, or contacts between federal legislators and foreign governments, has a significant impact on how other nations perceive U.S. policy. It challenges the prevailing understanding that diplomacy is solely a prerogative of the executive branch.

No, legislative diplomacy occurs in a constitutional void that imposes no limits on the conduct of members of Congress. This lack of guidance raises questions about the separation of powers and the extent of executive power.