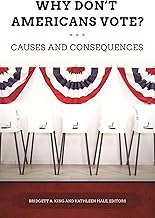

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, has long been a contentious issue in American politics. Critics argue that it undermines democratic principles by diluting the voting power of certain groups and entrenching partisan control. One of the most debated consequences of gerrymandering is its potential role in exacerbating political polarization. By creating safe districts where one party dominates, gerrymandering may reduce the incentive for politicians to appeal to moderate or opposing viewpoints, instead encouraging them to cater to their party’s base. This dynamic can deepen ideological divides, as elected officials prioritize partisan loyalty over bipartisan cooperation. Additionally, gerrymandering often marginalizes minority voices and reduces competitive elections, further polarizing the political landscape. While other factors, such as media echo chambers and demographic sorting, also contribute to polarization, gerrymandering remains a significant structural issue that warrants scrutiny in understanding the roots of America’s increasingly divided political climate.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition of Gerrymandering | Manipulating electoral district boundaries for political advantage. |

| Impact on Political Polarization | Studies suggest gerrymandering exacerbates polarization by creating safe seats for extremists. |

| Safe Seats Creation | Gerrymandering often results in districts dominated by one party, reducing competitive elections. |

| Reduced Incentive for Moderation | Politicians in safe seats cater to their base, discouraging bipartisan cooperation. |

| Voter Disenfranchisement | Minority viewpoints are often diluted, leading to underrepresentation. |

| Empirical Evidence | Research (e.g., American Political Science Review, 2021) links gerrymandering to increased polarization metrics. |

| State-Level Variations | Effects vary by state; states with stricter redistricting rules show less polarization. |

| Public Perception | Polls indicate widespread belief that gerrymandering contributes to polarization. |

| Legal and Policy Responses | Efforts to combat gerrymandering include independent redistricting commissions and court challenges. |

| Long-Term Trends | Polarization has risen alongside increased gerrymandering practices since the 1970s. |

| Counterarguments | Some argue polarization stems from other factors like media and ideological sorting, not just gerrymandering. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Impact on voter representation and district boundaries manipulation

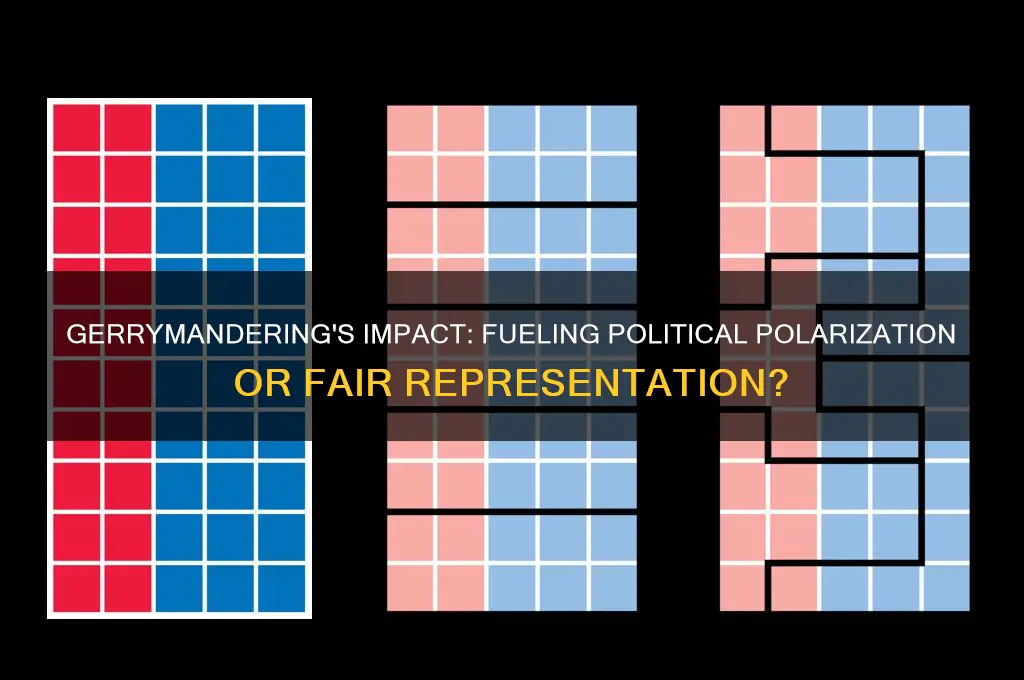

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, directly undermines voter representation by diluting the influence of certain groups. Consider a hypothetical state with 100 voters, 60 of whom support Party A and 40 Party B. Through strategic boundary manipulation, Party A could create districts where their supporters are concentrated in a few areas, leaving Party B supporters spread thinly across the remaining districts. This results in Party A winning a disproportionate number of seats despite not having a supermajority of voters. Such distortion of representation erodes trust in the democratic process, as voters perceive their voices as irrelevant or suppressed.

To illustrate, examine North Carolina’s 2016 redistricting, where Republicans drew maps that secured them 10 out of 13 congressional seats despite winning only 53% of the statewide vote. This manipulation involved "packing" Democratic voters into a few districts and "cracking" others across multiple Republican-leaning districts. The Supreme Court later deemed this an unconstitutional racial gerrymander, highlighting how boundary manipulation can disenfranchise minority voters, who often align with one party. This example underscores how gerrymandering not only skews political outcomes but also exacerbates polarization by marginalizing already underrepresented groups.

A step-by-step analysis reveals the mechanics of this manipulation:

- Data Collection: Parties use voter data (e.g., party affiliation, race, voting history) to identify target demographics.

- Boundary Drawing: Districts are redrawn to concentrate opposing voters in a few areas or disperse them to minimize their impact.

- Outcome: The party in control wins more seats than their vote share warrants, creating a mismatch between public will and political representation.

Caution must be taken when addressing gerrymandering, as solutions like independent redistricting commissions or algorithmic mapping are not foolproof. For instance, algorithms can inadvertently perpetuate biases if not carefully designed. Practical tips for voters include advocating for transparency in redistricting processes, supporting nonpartisan reforms, and engaging in local elections where gerrymandering often originates.

In conclusion, district boundary manipulation through gerrymandering systematically distorts voter representation, fueling political polarization. By prioritizing partisan gain over fair representation, this practice deepens divisions and undermines democratic legitimacy. Addressing it requires both structural reforms and active civic participation to ensure districts reflect the true will of the electorate.

Jimmies: A Politically Incorrect Term or Harmless Slang?

You may want to see also

Effects on partisan competition and safe seats creation

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party, significantly impacts partisan competition by creating safe seats. These are districts where one party consistently wins by large margins, reducing the incentive for competitive campaigning or meaningful voter engagement. For instance, in states like North Carolina and Pennsylvania, gerrymandered maps have led to congressional delegations that do not reflect the state’s overall partisan leanings, with one party dominating despite nearly even voter registration numbers.

Consider the mechanics: when districts are drawn to pack opposition voters into a few districts or crack them across many, the result is a dilution of their voting power. This minimizes the number of competitive races, as most districts become safe for one party. In the 2020 U.S. House elections, only 16 races were decided by a margin of 5% or less, the lowest number in decades. This trend undermines the principle of representative democracy, as elected officials in safe seats often cater to their party’s base rather than the broader electorate.

The creation of safe seats also discourages voter turnout and participation. In districts where the outcome is all but guaranteed, voters feel their ballots have little impact, leading to apathy. For example, in heavily gerrymandered states, turnout in safe districts can be 10-15% lower than in competitive ones. This further polarizes politics, as only the most ideologically committed voters participate, pushing elected officials toward more extreme positions to secure their base.

To mitigate these effects, reforms like independent redistricting commissions and algorithmic mapping tools are gaining traction. States like California and Michigan have adopted such measures, resulting in more competitive districts and increased voter engagement. For instance, after Michigan’s 2020 redistricting, the number of competitive state legislative races doubled compared to the previous decade. This demonstrates that reducing gerrymandering can restore balance to partisan competition and diminish the prevalence of safe seats.

In conclusion, gerrymandering’s role in creating safe seats stifles partisan competition, reduces voter turnout, and exacerbates political polarization. By prioritizing fair redistricting practices, states can foster more competitive elections, encourage broader voter participation, and ultimately create a more representative political system. The evidence is clear: addressing gerrymandering is essential for a healthier democracy.

The Political Foundations of the American Revolution: Shaping a New Nation

You may want to see also

Role in legislative extremism and policy gridlock

Gerrymandering, the practice of drawing legislative district lines to favor one political party over another, has been implicated in the rise of legislative extremism and policy gridlock. By creating safe seats for incumbents, gerrymandering reduces the number of competitive districts, thereby diminishing the incentive for politicians to appeal to moderate voters. Instead, they cater to their party’s base, often adopting more extreme positions to secure primary victories. This dynamic fosters a legislative environment where compromise becomes rare, and partisan agendas dominate, leading to policy gridlock.

Consider the mechanics of gerrymandering: when districts are redrawn to pack opposition voters into a few districts or crack them across many, the resulting seats are either overwhelmingly Democratic or Republican. In these safe districts, general elections become mere formalities, and the real contest shifts to primaries. Primary elections, with their lower turnout and more ideologically homogeneous electorates, reward candidates who take hardline stances. For instance, a Republican candidate in a deep-red district may feel compelled to embrace far-right policies to fend off challengers, while a Democrat in a deep-blue district may veer sharply left. This extremism trickles up to the legislature, where representatives are less inclined to collaborate across the aisle.

The consequences of this extremism are evident in policy gridlock. When legislators prioritize ideological purity over bipartisan solutions, meaningful legislation stalls. For example, issues like healthcare reform, climate change, and infrastructure investment often require compromise, but gerrymandered districts produce lawmakers who view compromise as betrayal. A study by the Brookings Institution found that states with heavily gerrymandered districts experienced a 10-15% decrease in the likelihood of passing bipartisan legislation compared to states with more competitive districts. This gridlock not only paralyzes governance but also erodes public trust in political institutions.

To mitigate these effects, reformers advocate for independent redistricting commissions and algorithmic approaches to drawing district lines. States like California and Arizona have already adopted such measures, resulting in more competitive districts and a greater willingness among legislators to work across party lines. For instance, California’s 2011 redistricting reform led to a 20% increase in the number of competitive seats, fostering a more moderate and collaborative legislative environment. While not a panacea, these reforms demonstrate that reducing gerrymandering can temper extremism and alleviate policy gridlock.

In practical terms, citizens can push for transparency in the redistricting process and support initiatives that remove map-drawing authority from partisan legislatures. Engaging in local advocacy, participating in public hearings, and leveraging technology to monitor redistricting efforts are actionable steps individuals can take. By addressing gerrymandering, we can begin to reverse the trends of legislative extremism and policy gridlock, paving the way for a more functional and responsive political system.

Assessing Bloomberg Politics: Reliability, Bias, and Accuracy in Reporting

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$9.99

$3.99 $12.99

$84.86 $147

Influence on electoral outcomes and voter turnout trends

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, significantly influences electoral outcomes by creating safe seats for incumbents and diluting the voting power of opposition supporters. For instance, in North Carolina’s 2016 congressional elections, Republicans secured 10 out of 13 seats despite winning only 53% of the statewide vote. This disparity highlights how gerrymandering can amplify a party’s representation beyond its actual voter support, skewing legislative bodies and policy outcomes in favor of the dominant party. Such manipulation undermines the principle of "one person, one vote," as voters in gerrymandered districts often feel their ballots carry less weight, particularly if they belong to the minority party.

The impact of gerrymandering on voter turnout trends is equally profound, often discouraging participation in districts deemed uncompetitive. When voters perceive their district as a safe seat for one party, they may feel their vote has little chance of influencing the outcome. A 2018 study by the Brennan Center found that turnout in heavily gerrymandered states like Maryland and Michigan was 5-10% lower compared to states with more neutral redistricting processes. This apathy is particularly evident among younger voters (ages 18-29) and minority groups, who are more likely to reside in densely packed, gerrymandered districts. Practical strategies to counteract this include voter education campaigns emphasizing the importance of local elections and the use of ranked-choice voting to give voters more meaningful choices.

To illustrate the causal link between gerrymandering and polarization, consider the case of Pennsylvania’s 2011 redistricting. The state’s map was so heavily gerrymandered in favor of Republicans that it was struck down by the state Supreme Court in 2018. Before the change, Pennsylvania’s congressional delegation was disproportionately Republican, despite the state’s relatively balanced electorate. After the new, fairer map was implemented, Democrats gained several seats, aligning representation more closely with the statewide vote. This example demonstrates how gerrymandering not only distorts electoral outcomes but also perpetuates polarization by entrenching partisan divides and reducing incentives for cross-party cooperation.

Addressing the influence of gerrymandering on electoral outcomes and voter turnout requires systemic reforms. Independent redistricting commissions, already in use in states like California and Arizona, can reduce partisan bias in map-drawing. Additionally, states should adopt transparency measures, such as public hearings and open data platforms, to ensure the process is accountable to citizens. For voters, staying informed about redistricting efforts and advocating for fair maps can help mitigate the negative effects of gerrymandering. Ultimately, dismantling this practice is essential to restoring faith in the electoral process and encouraging broader, more representative voter participation.

Gracefully Declining Sponsorship Offers: A Guide to Polite Rejection

You may want to see also

Relationship between gerrymandering and ideological sorting in politics

Gerrymandering, the practice of redrawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party over another, has long been scrutinized for its role in shaping political landscapes. One of its most significant yet often overlooked consequences is its contribution to ideological sorting—the phenomenon where voters and representatives become increasingly aligned with extreme ends of the political spectrum. This process exacerbates political polarization by creating districts that are overwhelmingly dominated by a single party, leaving little room for moderate voices or competitive elections.

Consider the mechanics of gerrymandering: when districts are redrawn, they are often crafted to pack voters from the opposing party into a few districts or crack them across multiple districts to dilute their influence. This results in "safe seats" where incumbents face minimal electoral pressure to appeal to the center. For instance, in North Carolina’s 2016 redistricting, Republicans drew maps that secured 10 out of 13 congressional seats despite winning only 53% of the statewide vote. Such districts incentivize candidates to cater to their party’s base rather than moderate voters, fostering ideological rigidity.

The relationship between gerrymandering and ideological sorting is further amplified by voter behavior. As districts become more homogenous, voters are less likely to encounter diverse viewpoints, reinforcing their existing beliefs. This echo chamber effect is compounded by representatives who, once elected, prioritize partisan loyalty over bipartisan cooperation. A study by the Brookings Institution found that gerrymandered districts are associated with a 10-15% increase in partisan voting patterns in Congress, illustrating how district lines can directly influence legislative behavior.

To mitigate this cycle, reforms such as independent redistricting commissions and algorithmic mapping tools have gained traction. States like California and Arizona have adopted independent commissions, reducing the incidence of extreme partisan bias in their maps. However, even these solutions are not foolproof; algorithmic tools, for example, can still reflect underlying demographic biases if not carefully calibrated. The key lies in balancing technological innovation with transparent, inclusive processes that prioritize fairness over partisan gain.

Ultimately, the relationship between gerrymandering and ideological sorting underscores a broader challenge in modern politics: the tension between representation and manipulation. While gerrymandering may provide short-term advantages for parties, its long-term impact on polarization threatens the health of democratic discourse. Addressing this issue requires not only structural reforms but also a cultural shift toward valuing compromise and diversity in political representation. Without such changes, gerrymandering will continue to be a driving force behind the ideological fragmentation of American politics.

Mastering the Art of Graceful Resignation: Tips for Giving Notice Politely

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Gerrymandering is the practice of drawing electoral district boundaries to favor one political party or group over another. It can contribute to political polarization by creating "safe" districts where one party dominates, reducing incentives for moderate candidates and encouraging extreme positions to appeal to the party base.

While gerrymandering can exacerbate political polarization, it is often both a cause and a symptom. Polarized legislatures are more likely to engage in gerrymandering, but the practice itself reinforces polarization by limiting competitive elections and marginalizing moderate voices.

Yes, gerrymandering can reduce accountability by creating districts where one party is guaranteed to win, making incumbents less responsive to the broader electorate. This can deepen polarization as officials focus on appealing to their party’s base rather than seeking bipartisan solutions.

Yes, solutions include independent or nonpartisan redistricting commissions, which remove partisan influence from the process. Additionally, reforms like proportional representation or multi-member districts can create more competitive elections and incentivize candidates to appeal to a broader spectrum of voters, potentially reducing polarization.