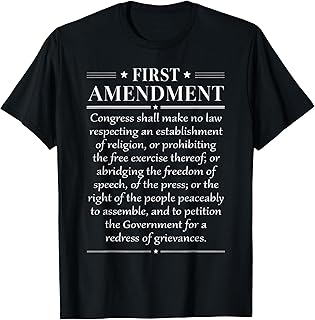

The question of whether the Constitution protects political dissent is a critical and enduring issue in democratic societies. Rooted in the First Amendment’s guarantees of free speech and assembly, the Constitution is often seen as a safeguard for individuals and groups to express dissenting opinions, challenge government policies, and advocate for change. However, the extent of this protection is not without limits, as courts and lawmakers have historically grappled with balancing dissent against concerns like national security, public order, and defamation. Landmark cases, such as *Brandenburg v. Ohio* and *Schenck v. United States*, have shaped the boundaries of protected speech, emphasizing that dissent is shielded unless it poses an imminent threat of lawless action. Despite these protections, challenges persist, including government surveillance, restrictive laws, and societal pressures that can chill dissent. Thus, the Constitution’s role in safeguarding political dissent remains a dynamic and contested arena, reflecting broader tensions between individual freedoms and collective stability.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Freedom of speech limits

The First Amendment's guarantee of free speech is not absolute. While it protects a wide range of expression, including political dissent, the Supreme Court has established limits to prevent harm and maintain order. One key restriction is on speech that incites imminent lawless action. For example, in *Brandenburg v. Ohio* (1969), the Court ruled that speech advocating violence is protected only if it’s not likely to produce such action immediately. This means a protester cannot lawfully call for a mob to storm a government building at that very moment, even if their cause is politically motivated.

Consider the practical implications of these limits. Organizers of political rallies must carefully craft their messages to avoid crossing this line. For instance, phrases like “let’s march to the Capitol and demand change” are generally protected, but “let’s break into the Capitol now” could lead to legal consequences. This distinction requires speakers to be precise in their language, especially in emotionally charged environments. A useful tip for activists: focus on advocating for change through legal means, such as voting or peaceful protest, to stay within constitutional bounds.

Another limit to free speech is defamation, which occurs when false statements harm someone’s reputation. Political dissent often involves criticism of public figures, but even they are protected against false claims that cause demonstrable harm. In *New York Times Co. v. Sullivan* (1964), the Court ruled that public officials must prove “actual malice”—knowledge of falsity or reckless disregard for the truth—to win a defamation suit. This standard is higher for public figures than for private individuals, reflecting the Constitution’s prioritization of robust debate over reputational protection.

Comparing U.S. law to international standards highlights its uniqueness. Many countries, such as Germany and France, criminalize hate speech or Holocaust denial, even if such speech doesn’t incite violence. In contrast, the U.S. protects offensive speech unless it meets specific criteria for restriction. This difference underscores the American commitment to prioritizing free expression, even when it’s uncomfortable or controversial. However, it also raises questions about the balance between protecting dissent and preventing harm in a diverse society.

Finally, fighting words and true threats are additional categories of unprotected speech. Fighting words, defined in *Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire* (1942), are those that inflict injury or provoke an immediate breach of peace. True threats, as outlined in *Virginia v. Black* (2003), are statements intended to frighten or intimidate. For example, a protester shouting racial slurs to incite a fight or sending a death threat to a politician would not be protected. These limits aim to prevent speech from escalating into physical harm, but they require careful application to avoid chilling legitimate dissent.

In navigating these limits, individuals must balance their right to express political disagreement with the legal boundaries set by the Constitution. Understanding these nuances is essential for anyone engaging in political activism, as it ensures their message remains both impactful and lawful.

Is AP News Politically Biased? Analyzing Its Neutrality and Reporting

You may want to see also

Political dissent vs. national security

The tension between political dissent and national security is a delicate balance that tests the resilience of constitutional protections. In democratic societies, the right to express dissenting views is often enshrined in foundational documents, yet this right can clash with the state's duty to safeguard its citizens from perceived threats. For instance, during times of war or heightened security concerns, governments may invoke emergency powers to restrict speech or assembly, arguing that such measures are necessary to protect national interests. However, history shows that these restrictions can easily become tools of oppression, silencing legitimate criticism and eroding democratic values. The challenge lies in defining the boundaries where dissent becomes a risk to security, a line that is often blurred and subject to interpretation.

Consider the case of whistleblowers, individuals who expose government or corporate wrongdoing in the public interest. While their actions can be seen as a form of political dissent, they are frequently labeled as threats to national security. Edward Snowden, for example, revealed extensive surveillance programs by the U.S. government, sparking a global debate about privacy and security. His actions were both celebrated as courageous and condemned as treasonous. This duality highlights the complexity of the issue: dissent can expose systemic flaws and hold power accountable, but it can also inadvertently compromise sensitive information. The constitutional protection of such dissent hinges on whether the act serves the greater good or undermines it, a judgment call that is rarely clear-cut.

To navigate this dilemma, a framework of proportionality and transparency is essential. Governments must demonstrate that any restriction on dissent is strictly necessary, narrowly tailored, and time-limited. For instance, laws that criminalize speech should require clear evidence of imminent harm, rather than speculative risks. Additionally, independent judicial oversight can act as a safeguard against abuse of power. Citizens, on the other hand, must exercise dissent responsibly, ensuring that their actions do not recklessly endanger others. Practical steps include verifying information before dissemination, using secure communication channels, and engaging in non-violent forms of protest. By adhering to these principles, societies can uphold both the right to dissent and the imperative of security.

A comparative analysis of global practices reveals varying approaches to this issue. In countries like Germany, where historical experiences with authoritarianism have shaped legal frameworks, the protection of dissent is robust, even when it challenges national security narratives. Conversely, in nations with weaker democratic institutions, dissent is often suppressed under the guise of security, leading to widespread censorship and human rights violations. These examples underscore the importance of a strong constitutional foundation that prioritizes both freedoms and safeguards. Ultimately, the goal is not to eliminate dissent but to channel it in ways that strengthen, rather than destabilize, the social fabric. Striking this balance requires constant vigilance, dialogue, and a commitment to democratic ideals.

John Krasinski's Political Views: Uncovering the Actor's Stance and Activism

You may want to see also

Assembly and protest rights

The right to assemble and protest is a cornerstone of democratic societies, enshrined in many constitutions worldwide. This fundamental freedom allows individuals to gather collectively, express dissent, and advocate for change. However, the extent of this protection varies significantly across jurisdictions, often sparking debates about the boundaries between lawful protest and public order.

Historical Context and Global Variations

Historically, assembly rights have been both celebrated and suppressed. The 1963 March on Washington, for instance, exemplified peaceful assembly, while the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 highlighted brutal suppression. Constitutions like the U.S. First Amendment explicitly protect "the right of the people peaceably to assemble," while others, like India’s Article 19, permit restrictions "in the interest of public order." In authoritarian regimes, such rights are often nonexistent or severely curtailed. This global disparity underscores the tension between individual freedoms and state authority.

Legal Frameworks and Limitations

Most democratic constitutions safeguard assembly rights but impose conditions. Common restrictions include time, place, and manner regulations, such as requiring permits for large gatherings. Courts often weigh the intent and impact of protests; for example, the European Court of Human Rights has upheld bans on protests deemed inciting violence. Notably, the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in *Schenck v. United States* (1919) introduced the "clear and present danger" test, which has since evolved to balance free speech with public safety. Understanding these legal nuances is crucial for organizers to navigate the boundaries of lawful protest.

Practical Tips for Organizers

When planning a protest, start by researching local laws governing assembly. In the U.S., notify authorities if your gathering exceeds 50 people in public spaces. In the UK, inform police under the Public Order Act 1986 if your march involves more than 20 participants. Always designate marshals to maintain order and communicate with law enforcement. Use social media responsibly to mobilize supporters but avoid language that could be construed as inciting violence. Finally, document the event—video evidence can be invaluable if legal disputes arise.

Case Studies and Takeaways

The 2020 Black Lives Matter protests in the U.S. illustrate both the power and challenges of assembly rights. While largely peaceful, some demonstrations faced police crackdowns, raising questions about disproportionate force. Conversely, Hong Kong’s 2019 anti-extradition protests faced severe repression, with authorities citing public safety to justify bans. These examples highlight the importance of strategic planning and legal awareness. Organizers must leverage constitutional protections while anticipating potential pushback, ensuring their message resonates without escalating into chaos.

The Future of Assembly Rights

As digital spaces increasingly host activism, the definition of "assembly" is evolving. Virtual protests, like those on social media, test traditional legal frameworks. Governments are responding with laws targeting online dissent, blurring the line between free speech and censorship. Advocates must remain vigilant, pushing for interpretations of assembly rights that reflect the realities of modern communication. Ultimately, the protection of political dissent hinges on a society’s commitment to upholding these rights, even—or especially—when the message challenges the status quo.

Is Political Collusion Illegal? Unraveling the Legal and Ethical Boundaries

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Sedition laws and constitutionality

Sedition laws, which criminalize speech deemed to incite rebellion or resistance against the government, have long been a contentious issue in the context of constitutional protections for political dissent. The tension between maintaining national security and upholding free speech rights is palpable, as evidenced by historical and contemporary legal battles. For instance, the 1918 Sedition Act in the United States, an extension of the Espionage Act, led to the prosecution of individuals for expressing anti-war sentiments, raising questions about the limits of government power during times of crisis.

Analyzing the constitutionality of sedition laws requires a deep dive into the First Amendment, which guarantees freedom of speech and assembly. The Supreme Court’s 1969 decision in *Brandenburg v. Ohio* established the "imminent lawless action" test, ruling that speech is protected unless it is directed to and likely to incite immediate illegal activity. This standard effectively narrowed the scope of sedition laws, emphasizing that mere advocacy of unpopular or radical ideas is not sufficient for criminal liability. However, the ambiguity in defining "imminent" and "likely" leaves room for interpretation, potentially allowing for abuse in the application of such laws.

Instructively, countries with robust constitutional frameworks often grapple with balancing sedition laws and free speech. India’s sedition law, Section 124A of the Penal Code, has been criticized for being used to suppress political dissent, particularly against activists and journalists. In contrast, the United Kingdom repealed its sedition laws in 2009, reflecting a shift toward prioritizing free expression over punitive measures. These examples highlight the importance of clear, narrowly tailored legislation to prevent the chilling effect on legitimate political discourse.

Persuasively, the argument against sedition laws hinges on their potential to stifle democratic debate. Political dissent is a cornerstone of a healthy democracy, serving as a check on government power and fostering accountability. Sedition laws, when broadly interpreted, can criminalize legitimate criticism, creating an environment of fear and self-censorship. For instance, during the Civil Rights Movement in the U.S., activists were often labeled as seditious, yet their efforts ultimately led to transformative legal and social change. This underscores the need to protect even the most controversial speech to preserve the integrity of democratic institutions.

Comparatively, the approach to sedition laws varies widely across jurisdictions, reflecting differing cultural and historical contexts. While some countries retain such laws as a tool for maintaining order, others have moved away from them in favor of more nuanced approaches to addressing threats to national security. A practical takeaway is that the constitutionality of sedition laws depends on their specificity and adherence to international human rights standards. Laws that are vague or overly broad risk infringing on fundamental freedoms, while those narrowly focused on preventing violence or harm may withstand constitutional scrutiny.

In conclusion, the interplay between sedition laws and constitutional protections for political dissent is complex and context-dependent. By examining historical precedents, legal standards, and international practices, it becomes clear that the key lies in striking a balance that safeguards both national security and the right to free expression. Policymakers and legal practitioners must approach this issue with caution, ensuring that any restrictions on speech are justified, proportionate, and respectful of democratic values.

Understanding State Politics: Mechanisms, Power Dynamics, and Policy-Making Processes

You may want to see also

Protection of minority opinions

The protection of minority opinions is a cornerstone of democratic societies, ensuring that diverse voices are not silenced by the majority. Constitutional frameworks often enshrine this principle, recognizing that dissent fosters innovation, challenges stagnation, and safeguards against tyranny. For instance, the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution explicitly protects freedom of speech and assembly, providing a legal shield for minority viewpoints. Similarly, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees freedom of expression, even for opinions that may be unpopular or controversial. These provisions underscore the importance of creating a space where all voices, regardless of their alignment with mainstream thought, can be heard.

However, protecting minority opinions is not without challenges. Practical implementation often requires balancing competing interests, such as public safety or social cohesion. For example, hate speech laws in many countries restrict expressions that incite violence or discrimination, even if they represent minority views. This raises the question: where do we draw the line between protecting dissent and preventing harm? Courts and policymakers must navigate this delicate terrain, ensuring that restrictions on speech are narrowly tailored and justified by compelling state interests. A case in point is the European Court of Human Rights, which has upheld the prohibition of Holocaust denial in some countries while emphasizing the need for proportionality in such measures.

To effectively protect minority opinions, individuals and institutions must adopt proactive strategies. Education plays a critical role in fostering tolerance and understanding, equipping citizens to engage with diverse perspectives respectfully. Media outlets, too, have a responsibility to amplify underrepresented voices, rather than prioritizing sensationalism or majority viewpoints. On a personal level, individuals can practice active listening, seeking to understand opposing viewpoints before forming judgments. For instance, community dialogues or debate forums can provide structured spaces for minority opinions to be expressed and considered. These efforts, combined with robust legal protections, create a more inclusive public sphere.

Comparatively, nations with weaker constitutional safeguards for minority opinions often face greater social fragmentation and political instability. In authoritarian regimes, dissent is frequently suppressed, leading to widespread disillusionment and underground resistance movements. Even in democracies, erosion of these protections—whether through legislative overreach or societal apathy—can undermine trust in institutions. The 2021 storming of the U.S. Capitol serves as a cautionary tale, highlighting the consequences of dismissing minority grievances without constructive engagement. By contrast, countries like Sweden and the Netherlands, which consistently rank high in press freedom and civic participation, demonstrate the resilience of societies that prioritize inclusive discourse.

Ultimately, the protection of minority opinions is not merely a legal obligation but a moral imperative. It reflects a commitment to pluralism, recognizing that truth and progress emerge from the clash of ideas. While challenges persist, the tools to safeguard this principle—strong constitutional frameworks, educational initiatives, and civic engagement—are within reach. As societies grapple with polarization and misinformation, the enduring lesson is clear: democracy thrives not by silencing dissent, but by embracing it. Practical steps, such as advocating for inclusive policies, supporting independent media, and fostering dialogue, can ensure that minority opinions remain a vital force in shaping a just and equitable world.

Attack on Titan: Unveiling the Political Underbelly of a Dystopian Saga

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the Constitution protects political dissent through the First Amendment, which guarantees freedoms of speech, assembly, and petition.

The First Amendment’s protections of free speech, peaceful assembly, and the right to petition the government are the primary safeguards for political dissent.

Yes, the government can limit political dissent if it poses a clear and present danger, incites imminent lawless action, or falls into other narrowly defined exceptions, such as defamation or true threats.

No, the Constitution does not protect violent or unlawful actions. Only peaceful and non-disruptive forms of dissent are protected under the First Amendment.

Yes, landmark cases like *Brandenburg v. Ohio* (1969) and *West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette* (1943) have reinforced the Constitution’s protection of political dissent and free speech.

![The First Amendment: [Connected Ebook] (Aspen Casebook) (Aspen Casebook Series)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61p49hyM5WL._AC_UL320_.jpg)