China's human rights record has long been a subject of international scrutiny, with one of the most contentious issues being the existence of political prisoners within its borders. Critics and human rights organizations argue that the Chinese government frequently detains individuals for expressing dissenting political views, practicing certain religions, or advocating for greater autonomy in regions like Tibet and Xinjiang. These detainees are often charged under broadly defined laws such as subversion of state power or inciting ethnic hatred, which are seen as tools to suppress opposition and maintain the Communist Party’s control. While China denies holding political prisoners, claiming instead that these individuals are lawfully prosecuted for criminal offenses, reports from activists, journalists, and international bodies suggest otherwise, painting a picture of systemic repression and arbitrary detention. This ongoing debate highlights the tension between China’s sovereignty and global human rights standards, raising questions about transparency, accountability, and the rule of law in the country.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Existence of Political Prisoners | Yes, widely acknowledged by international human rights organizations. |

| Estimated Number | Thousands (exact figures vary; estimates range from 1,000 to several thousand). |

| Legal Basis for Detention | Often charged under broadly defined laws like "subversion of state power," "inciting separatism," or "picking quarrels and provoking trouble." |

| Targeted Groups | Human rights activists, dissidents, ethnic minorities (e.g., Uyghurs, Tibetans), journalists, and religious practitioners. |

| Detention Facilities | Prisons, re-education camps (e.g., Xinjiang internment camps), and black jails. |

| International Stance | Condemned by the UN, U.S., EU, and other countries; China denies allegations, claiming actions are for national security. |

| Recent Developments | Increased crackdown on dissent in Hong Kong under the National Security Law (2020). |

| Notable Cases | Ilham Tohti (Uyghur scholar), Joshua Wong (Hong Kong activist), and others. |

| Transparency | Limited; lack of access to detainees and independent investigations. |

| Human Rights Concerns | Reports of torture, forced labor, and cultural repression in detention. |

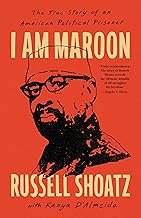

Explore related products

$12.24 $18

What You'll Learn

Definition of Political Prisoners

The term "political prisoner" is often invoked in discussions about China's human rights record, but its definition is far from straightforward. At its core, a political prisoner is someone detained for their political beliefs, activities, or affiliations rather than for any criminal offense. However, the line between political dissent and criminal behavior is often blurred, especially in authoritarian regimes where the state tightly controls the narrative. In China, individuals labeled as political prisoners frequently include activists, journalists, lawyers, and members of ethnic or religious minorities whose actions are deemed threatening to the ruling Communist Party. Understanding this definition requires examining not only the legal charges but also the broader context of state repression and the intent behind the detention.

To define a political prisoner, one must consider the criteria established by international organizations like Amnesty International. According to Amnesty, a political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political or religious beliefs, ethnicity, or other conscientiously held views, provided they have not used or advocated violence. This definition excludes those who have committed common crimes or acts of violence, even if they are politically motivated. Applying this framework to China reveals a pattern of arrests targeting individuals who challenge the government’s authority, such as advocates for democracy, Tibetan independence, or Uyghur rights. For instance, cases like that of Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate who died in custody, highlight how China’s legal system is often weaponized to silence dissent under the guise of maintaining social stability.

A comparative analysis of China’s treatment of political prisoners sheds light on the unique challenges in defining this term within its context. Unlike democracies, where political dissent is generally protected, China’s legal system is designed to prioritize state security over individual freedoms. Charges such as "subversion of state power" or "inciting ethnic hatred" are frequently used to prosecute dissidents, even when their actions are non-violent. This raises questions about the legitimacy of such charges and whether they are politically motivated. For example, the mass detention of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, which China justifies as a counterterrorism measure, is widely regarded by human rights organizations as a form of political repression targeting an ethnic minority.

In practice, identifying political prisoners in China requires a nuanced approach that accounts for the state’s control over information and its ability to manipulate legal processes. Activists and observers must rely on firsthand accounts, leaked documents, and patterns of behavior to document cases of political imprisonment. This is complicated by China’s lack of judicial independence and the opacity of its legal system. For those seeking to advocate for political prisoners, it is crucial to amplify their stories, pressure international bodies to hold China accountable, and support organizations that provide legal aid and humanitarian assistance. While the definition of a political prisoner may seem clear in theory, its application in China’s complex political landscape demands vigilance and persistence.

Mastering Political Philosophy: Essential Steps for Understanding Core Concepts

You may want to see also

Cases of Dissidents in China

China's treatment of dissidents offers a stark illustration of the tension between state control and individual expression. One prominent example is the case of Liu Xiaobo, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate who died in custody in 2017. Liu was sentenced to 11 years in prison for "inciting subversion of state power" after co-authoring Charter 08, a manifesto calling for democratic reforms. His case highlights the severe consequences faced by those who challenge the Chinese Communist Party's (CCP) authority, even when their advocacy is peaceful and rooted in internationally recognized human rights principles.

Consider the plight of Uyghur scholar Ilham Tohti, sentenced to life in prison in 2014 on separatism-related charges. Tohti, an economics professor, had advocated for the rights of China's Uyghur Muslim minority through his website, *Uyghur Online*. His imprisonment exemplifies the CCP's zero-tolerance policy toward dissent in Xinjiang, where an estimated 1 million Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities have been detained in re-education camps. Tohti's case underscores how academic and cultural advocacy can be criminalized under the guise of maintaining social stability.

A comparative analysis reveals that China's approach to dissent differs markedly from Western democracies. While countries like the U.S. or Germany may prosecute individuals for hate speech or terrorism, China's legal system often conflates political dissent with criminal activity. For instance, the charge of "picking quarrels and provoking trouble" has been used to detain activists like Huang Qi, who documented human rights abuses. This broad and vaguely defined offense allows authorities to silence critics with minimal legal scrutiny, effectively criminalizing free speech.

To navigate this landscape, activists and observers must adopt strategic caution. Documenting abuses through trusted international organizations, such as Human Rights Watch or Amnesty International, can amplify cases like those of lawyer Gao Zhisheng, who disappeared into custody after exposing torture. Additionally, leveraging global platforms—like the United Nations or the European Parliament—can pressure China to address specific cases. However, such efforts must balance visibility with the safety of individuals, as heightened attention can sometimes lead to harsher treatment.

Ultimately, the cases of Liu Xiaobo, Ilham Tohti, and others serve as a reminder that dissent in China is not merely a political act but a high-stakes gamble. While the CCP's grip on power appears unyielding, the resilience of these individuals underscores the enduring human desire for freedom and justice. Their stories demand not just awareness but sustained, strategic action to hold China accountable for its treatment of political prisoners.

Mastering Office Politics: Strategies for Success and Career Advancement

You may want to see also

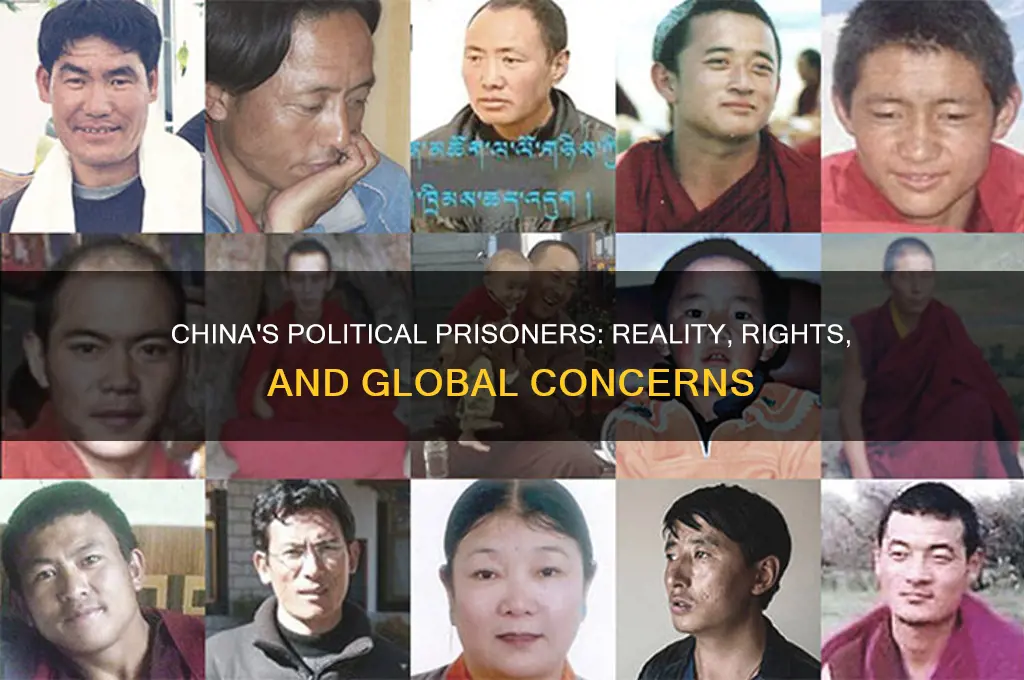

Xinjiang Detention Camps

The Xinjiang detention camps, officially termed "vocational education and training centers" by the Chinese government, have become a focal point in the global debate over political imprisonment. Since 2017, an estimated 1 to 1.8 million Uyghur Muslims and other ethnic minorities have been detained in these facilities, according to reports from human rights organizations and leaked government documents. The stated purpose is to combat extremism and provide job training, but evidence suggests a far more sinister agenda: cultural erasure and political indoctrination. Detainees are subjected to forced Mandarin lessons, ideological re-education, and, in some cases, physical abuse, all under the guise of national security.

Consider the scale and methodology of these camps. Satellite imagery and firsthand accounts reveal sprawling complexes surrounded by high walls, watchtowers, and barbed wire—features more akin to high-security prisons than educational centers. Former detainees describe overcrowded cells, forced labor in nearby factories, and strict surveillance, including biometric monitoring. The Chinese government’s own documents, such as the "Karakax List," detail criteria for detention, which include behaviors like "wearing a veil" or "refusing to watch state television." These criteria underscore the political nature of the camps, targeting individuals not for criminal acts but for their cultural and religious practices.

From a comparative perspective, the Xinjiang camps echo historical instances of mass detention for political and ethnic suppression. Parallels can be drawn to the Soviet Gulag system or the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, where entire groups were targeted based on perceived disloyalty. However, the Xinjiang case is unique in its use of modern technology, such as facial recognition and predictive policing, to identify and monitor potential dissenters. This blend of traditional repression with digital surveillance sets a dangerous precedent for authoritarian regimes worldwide.

For those seeking to understand or address this issue, practical steps include supporting organizations like the Uyghur Human Rights Project or Amnesty International, which document abuses and advocate for accountability. Individuals can also pressure governments and corporations to condemn the camps and sever economic ties with entities benefiting from forced labor in Xinjiang. While diplomatic efforts face challenges due to China’s global influence, grassroots campaigns and international scrutiny have begun to yield results, such as sanctions and import bans on Xinjiang-produced goods.

Ultimately, the Xinjiang detention camps serve as a stark example of how political imprisonment can be disguised as social welfare. The systematic targeting of a minority group for their identity, rather than their actions, challenges the very notion of justice and human rights. As the world grapples with this crisis, the question remains: will the international community prioritize economic and geopolitical interests over the plight of millions, or will it stand firm against this modern-day atrocity?

Tune Out the Noise: Mastering the Art of Ignoring Political Pundits

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$26.03 $27.99

$17.84 $38

Hong Kong Activists Arrested

The arrest of Hong Kong activists under the National Security Law (NSL) enacted in 2020 exemplifies China’s use of legal frameworks to suppress dissent, raising questions about political imprisonment. Prominent figures like Joshua Wong, Agnes Chow, and media tycoon Jimmy Lai have been detained for activities deemed subversive, including organizing pro-democracy protests and advocating for autonomy. These arrests target not just individuals but the broader movement for democratic freedoms in Hong Kong, signaling a crackdown on political expression.

Analyzing the NSL reveals its broad and ambiguous language, which criminalizes acts of secession, subversion, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces. Critics argue this vagueness allows authorities to interpret legitimate political activism as criminal behavior. For instance, participating in unauthorized protests or calling for international support can lead to charges carrying up to life imprisonment. This legal tool effectively silences opposition, as activists face severe consequences for exercising rights previously protected under Hong Kong’s Basic Law.

Comparatively, the treatment of Hong Kong activists mirrors patterns seen in mainland China, where dissidents like Liu Xiaobo and Ilham Tohti were imprisoned for advocating democracy and minority rights. However, Hong Kong’s case is unique due to its historical context as a semi-autonomous region under the "One Country, Two Systems" framework. The erosion of this system through the NSL and subsequent arrests underscores a shift toward mainland-style governance, where political dissent is systematically criminalized.

For those monitoring or supporting Hong Kong’s pro-democracy movement, practical steps include staying informed about legal developments, supporting international advocacy efforts, and amplifying the voices of detained activists. Caution is advised when engaging in activism within Hong Kong, as even symbolic acts like displaying protest slogans can now lead to arrest. The takeaway is clear: the arrests of Hong Kong activists are not isolated incidents but part of a broader strategy to eliminate political opposition, reinforcing the argument that China detains individuals for their political beliefs and actions.

Are Political Favor Hires Legal? Exploring Ethics and Legal Boundaries

You may want to see also

International Criticism and Response

China's treatment of political prisoners has drawn sharp international criticism, with human rights organizations, foreign governments, and activists condemning practices deemed repressive and opaque. Reports from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the United Nations highlight systemic issues such as arbitrary detentions, forced labor, and torture in facilities like Xinjiang’s "re-education camps" and Tibet’s prisons. These allegations are often supported by satellite imagery, firsthand testimonies, and leaked government documents, painting a grim picture of state-sanctioned abuses targeting Uyghurs, Tibetans, Falun Gong practitioners, and political dissidents.

In response, China has consistently denied these claims, framing them as Western-led smear campaigns aimed at undermining its sovereignty and development. Chinese officials argue that their actions are necessary for national security, social stability, and counterterrorism efforts. They point to economic progress in regions like Xinjiang and Tibet as evidence of their commitment to improving citizens’ lives. Diplomatic responses often include accusations of hypocrisy, with China highlighting human rights issues in criticizing countries, such as racial inequality in the U.S. or historical colonialism in Europe.

Internationally, the response has been mixed. While the U.S., Canada, and the European Union have imposed sanctions on Chinese officials and entities linked to human rights abuses, other nations, particularly those in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, have supported China’s stance. This divide reflects broader geopolitical tensions and economic dependencies, as many countries rely on trade with China or avoid antagonizing a global superpower. Multilateral efforts, such as UN resolutions or independent investigations, have been stymied by China’s influence in international bodies.

Practical steps for addressing this issue include targeted sanctions, travel bans, and export controls on surveillance technology used in oppressive campaigns. Advocacy groups recommend pressuring corporations to ensure their supply chains are free from forced labor, particularly in industries like textiles and electronics. Individuals can contribute by supporting organizations documenting abuses, raising awareness through social media, and urging their governments to prioritize human rights in diplomatic engagements with China.

Ultimately, the international community faces a delicate balance between holding China accountable and maintaining constructive dialogue. While criticism has raised global awareness, tangible change remains elusive. A sustained, coordinated approach—combining diplomatic pressure, economic incentives, and grassroots advocacy—may offer the best hope for alleviating the plight of China’s political prisoners.

Cindy McCain's Political Journey: From Philanthropy to Public Service

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, China is widely recognized as holding political prisoners, including activists, dissidents, and members of ethnic and religious minorities who have been detained for their political beliefs or activities.

China does not officially recognize the term "political prisoner." Instead, individuals are often charged under broadly defined laws such as "subversion of state power," "inciting separatism," or "endangering national security."

Common targets include Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang, Tibetan Buddhists, Falun Gong practitioners, human rights activists, democracy advocates, and journalists who criticize the government.

Exact numbers are difficult to verify due to lack of transparency, but human rights organizations estimate that tens of thousands of individuals are detained for political reasons, particularly in regions like Xinjiang and Tibet.

Many countries, international organizations, and human rights groups have condemned China's treatment of political prisoners, calling for their release and greater transparency. Sanctions and diplomatic pressures have been applied in some cases.