China's human rights record, particularly regarding the treatment of political dissidents, has long been a subject of international scrutiny and debate. While the Chinese government maintains that it upholds the rule of law and respects human rights, allegations persist that it employs harsh measures, including execution, to suppress dissent and maintain political control. Reports from human rights organizations, journalists, and former detainees suggest that individuals deemed threats to the Communist Party’s authority—such as activists, lawyers, and members of religious or ethnic minorities—often face arbitrary detention, torture, and, in some cases, capital punishment. However, due to the opacity of China’s legal system and restrictions on independent investigations, definitive evidence of executions specifically targeting political dissidents remains difficult to obtain, leaving the issue shrouded in controversy and uncertainty.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Execution of Political Dissidents | China has a history of executing individuals for political dissent, though official data is limited due to opacity in legal proceedings. |

| Legal Framework | Charges often include "subversion of state power" or "splitting the state," which can carry the death penalty under Chinese law. |

| Recent Cases | Specific recent cases are not publicly documented due to government censorship, but human rights organizations report ongoing repression. |

| Transparency | Lack of transparency in judicial processes makes it difficult to verify exact numbers or details of executions. |

| International Criticism | China faces widespread international condemnation for its treatment of political dissidents, including allegations of arbitrary executions. |

| Notable Examples | Historical examples include the execution of activists like Wei Jingsheng and more recent crackdowns on Uyghur activists in Xinjiang. |

| Current Trends | Increased use of extrajudicial measures, such as enforced disappearances and re-education camps, alongside potential executions. |

| Government Stance | Chinese authorities deny systematic execution of political dissidents, claiming actions are taken against "criminals" threatening national security. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Historical Cases of Executions

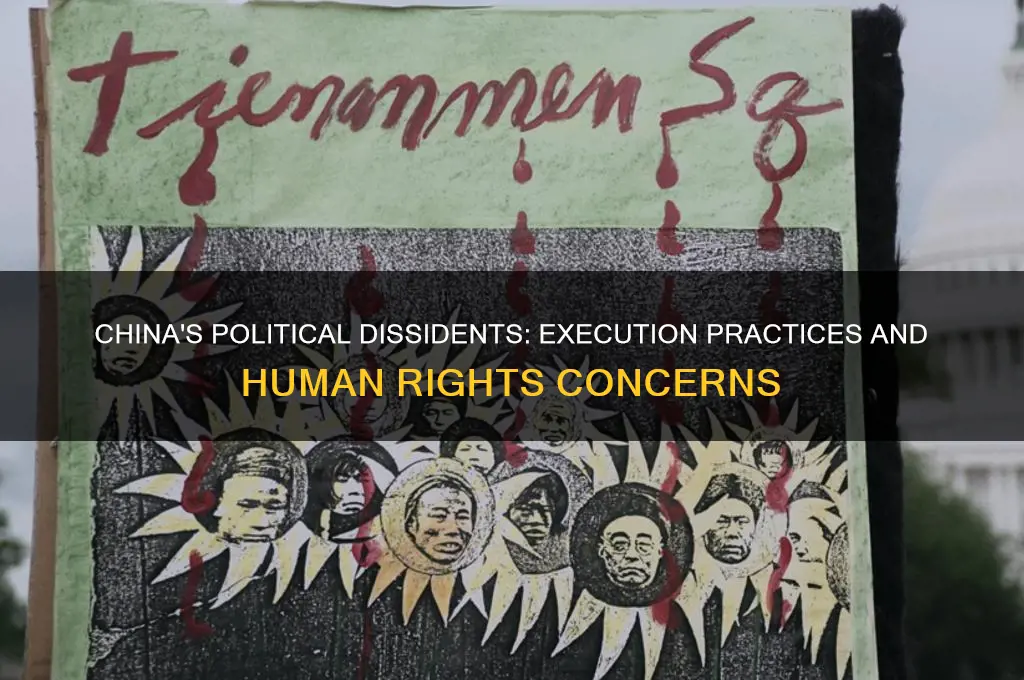

China's history of executing political dissidents is marked by high-profile cases that have drawn international scrutiny. One of the most notorious examples is the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, where pro-democracy activists were brutally suppressed. While the exact number of executions remains unclear due to government secrecy, it is widely believed that several individuals were sentenced to death for their roles in the movement. For instance, students like Wang Weiping and Chen Yong were reportedly executed for "counter-revolutionary crimes," a charge often used to silence dissent. These cases highlight the government's willingness to use capital punishment as a tool to quell political opposition.

Analyzing the legal framework, China’s use of the death penalty for political dissent is rooted in its broad and ambiguous criminal laws. Articles like "subversion of state power" and "inciting splittism" in the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China have been employed to target activists, intellectuals, and minority groups. For example, in 2014, Uyghur scholar Ilham Tohti was sentenced to life in prison on separatism charges, though not executed, his case exemplifies how political dissent is criminalized. The lack of transparency in trials and the frequent use of coerced confessions further underscore the system’s potential for abuse.

A comparative look at historical cases reveals a pattern of targeting specific groups during periods of perceived threat. During the Anti-Rightist Campaign (1957–1959), thousands of intellectuals were purged, with some executed for criticizing the Communist Party. Similarly, the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) saw mass executions of "class enemies," including political dissidents. In contrast, the post-1980s era has seen a shift toward more covert methods of suppression, such as enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings, though executions still occur. This evolution suggests a calculated approach to balancing domestic control with international image management.

For those studying or advocating against such practices, understanding the historical context is crucial. Practical steps include documenting cases through reliable sources, such as human rights organizations like Amnesty International or Human Rights Watch, and cross-referencing state media reports with independent accounts. Additionally, leveraging international legal mechanisms, such as UN resolutions or the International Criminal Court, can pressure China to address these abuses. However, caution must be exercised, as direct criticism often leads to diplomatic backlash or further repression of activists within China.

In conclusion, historical cases of executions in China demonstrate a systemic approach to silencing political dissent. From the Tiananmen Square protests to the persecution of minority groups, the state has consistently used capital punishment and related charges to maintain control. While methods have evolved, the underlying strategy remains intact. For researchers, activists, and policymakers, these cases serve as a stark reminder of the challenges in advocating for human rights in an authoritarian regime. By focusing on documentation, international pressure, and strategic advocacy, meaningful progress can be made toward accountability and justice.

Do Political Donations Influence Elections and Policy Decisions?

You may want to see also

Legal Framework and Charges

China's legal framework provides a veneer of legitimacy to the suppression of political dissent, often blurring the lines between criminal acts and protected speech. The primary legal instrument is the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China, which includes vaguely worded provisions such as "inciting subversion of state power" (Article 105) and "splittism" (Article 103). These charges are broadly defined, allowing authorities to target individuals whose activities may include peaceful advocacy, criticism of the government, or even private discussions deemed threatening. For instance, the charge of "subversion" has been used against activists like Liu Xiaobo, a Nobel Peace Prize laureate who was sentenced to 11 years in prison for co-authoring Charter 08, a manifesto calling for political reform.

The process of bringing charges against political dissidents often involves a combination of legal and extralegal tactics. Initial steps typically include surveillance, house arrest, or detention under "residential surveillance at a designated location," which can last up to six months without formal charges. During this period, access to legal counsel is frequently restricted, and coerced confessions are not uncommon. Once charges are filed, trials are often brief and lack transparency, with conviction rates exceeding 99%. The use of state secrets laws further complicates matters, as defendants and their lawyers are barred from disclosing details of the case, effectively shielding the proceedings from public scrutiny.

A comparative analysis reveals how China’s legal framework contrasts with international standards. While countries like the United States or Germany narrowly define crimes against the state to protect free speech, China’s laws prioritize regime stability over individual rights. For example, the European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly ruled that political dissent, even if critical of the government, is protected under Article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights. In China, however, such dissent is criminalized, and the judiciary, which is subordinate to the Communist Party, rarely acts as an independent check on executive power. This systemic lack of judicial independence underscores the fragility of legal protections for dissidents.

Practical implications of these charges extend beyond imprisonment to include social and economic repercussions. Individuals convicted of political crimes often face lifelong stigma, with restrictions on employment, travel, and even access to education for their families. For example, the children of dissidents may be barred from attending prestigious universities or joining the civil service. Additionally, the use of "re-education through labor" (abolished in 2013 but replaced by similar measures) and extrajudicial detention in facilities like Xinjiang’s "vocational training centers" highlights how legal charges can serve as a gateway to broader human rights abuses.

In conclusion, China’s legal framework functions as a tool to neutralize political dissent under the guise of maintaining social order. The broad and ambiguous nature of charges like "subversion" and "splittism," coupled with a lack of judicial independence, ensures that the system is tilted against dissidents. While execution for purely political offenses is rare, the harsh penalties and extralegal measures employed serve as a powerful deterrent. For activists, lawyers, and international observers, understanding this framework is crucial for advocating reform and holding China accountable to its obligations under international law.

Mastering Polite Profanity: How to Swear with Class and Grace

You may want to see also

International Reactions and Criticism

China's alleged execution of political dissidents has sparked a spectrum of international reactions, from muted diplomatic statements to vocal condemnations. Western nations, led by the United States and the European Union, frequently issue public rebukes, citing human rights violations and calling for transparency. For instance, the U.S. State Department’s annual human rights report consistently highlights China’s use of capital punishment against political opponents, often linking it to broader concerns about arbitrary detention and forced confessions. These criticisms are amplified by international NGOs like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, which document specific cases and advocate for global pressure on Beijing.

Contrastingly, many non-Western countries adopt a more cautious approach, prioritizing economic and strategic ties over public criticism. Nations in Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East often abstain from voting on UN resolutions condemning China’s human rights record, reflecting a reluctance to alienate a major trade partner. This divide underscores a global tension between moral imperatives and pragmatic interests, with some arguing that quiet diplomacy is more effective than public shaming. However, this approach risks normalizing China’s actions, as it lacks the collective force needed to drive meaningful change.

The international community’s response is further complicated by China’s strategic use of economic leverage and diplomatic influence. Beijing has been known to retaliate against critical nations through trade restrictions, visa denials, or diplomatic boycotts, as seen in its strained relations with Australia and Sweden following their criticisms. This has a chilling effect on smaller nations, which may self-censor to avoid economic repercussions. Meanwhile, China counters accusations by framing them as Western interference in its internal affairs, leveraging its global platforms to promote narratives of sovereignty and cultural relativism.

Despite these challenges, grassroots movements and transnational advocacy networks continue to push for accountability. Campaigns like #SaveUyghurs and #FreeHongKong have mobilized global public opinion, pressuring governments and corporations to take a stand. For individuals and organizations seeking to contribute, practical steps include supporting verified NGOs, amplifying credible reports on social media, and urging local representatives to prioritize human rights in foreign policy. While systemic change remains elusive, sustained international pressure can create cracks in China’s impunity, offering hope for those at risk.

Combating Political Corruption: Strategies for Transparency, Accountability, and Ethical Governance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$58.89 $61.99

$39.8

Recent High-Profile Dissident Cases

China's treatment of political dissidents has long been a subject of international scrutiny, with recent high-profile cases underscoring the severity of its approach. One notable example is the detention and alleged torture of human rights lawyer Gao Zhisheng, who disappeared into state custody multiple times over the past decade. Gao's case exemplifies the Chinese government's strategy of silencing critics through prolonged detention, forced confessions, and psychological coercion. His ordeal highlights the risks faced by those who dare to challenge the Communist Party's authority, even through legal means.

Another striking case is that of Ilham Tohti, a Uyghur economist and advocate for ethnic minority rights, who was sentenced to life in prison in 2014 on charges of "separatism." Tohti's imprisonment has drawn widespread condemnation from international human rights organizations, which argue that his advocacy was peaceful and within the bounds of free speech. His case is emblematic of China's broader crackdown on Uyghur intellectuals and activists in Xinjiang, where mass detentions and cultural suppression have reached unprecedented levels. Tohti's plight serves as a stark reminder of the government's intolerance for dissent, particularly on issues of ethnic and religious identity.

The disappearance of Swedish bookseller Gui Minhai further illustrates China's extraterritorial reach in targeting dissidents. Abducted from Thailand in 2015, Gui was forced to make televised confessions before being sentenced to 10 years in prison for "illegally providing intelligence overseas." His case has strained China's relations with Sweden and exposed the lengths to which Beijing will go to silence critics, even those operating outside its borders. Gui's story underscores the global nature of China's campaign against dissent, raising concerns about the safety of activists and intellectuals worldwide.

While execution of political dissidents is less common than other forms of repression, the case of Tibetans and Uyghurs accused of "terrorism" or "separatism" has occasionally resulted in death sentences. For instance, in 2020, reports emerged of Uyghur poet and publisher Memetjan Abdulla being sentenced to death, though details remain scarce due to state censorship. Such cases, though not widespread, signal the extreme measures China is willing to take to quell perceived threats to its unity. The rarity of executions does not diminish the chilling effect they have on dissent, as the threat of severe punishment looms large over activists and minority groups.

In analyzing these cases, a pattern emerges: China employs a spectrum of tactics to suppress dissent, ranging from detention and torture to life imprisonment and, in rare instances, execution. The government's approach is calculated to instill fear and discourage opposition, both domestically and internationally. For those advocating for human rights or minority rights, the risks are immense, yet these high-profile cases also galvanize global attention and solidarity. Practical steps for activists include leveraging international platforms to amplify voices, documenting abuses meticulously, and fostering alliances with global human rights organizations to increase pressure on Beijing. While the path to change is fraught, these cases remind us that the fight for freedom and justice persists, even in the face of overwhelming odds.

Crafting Believable Fantasy Politics: A Guide to World-Building and Intrigue

You may want to see also

Comparative Global Practices on Dissent

China's approach to political dissent, marked by stringent censorship and punitive measures, contrasts sharply with practices in democratic societies, where dissent is often protected as a cornerstone of civic engagement. While China’s legal framework allows for the execution of individuals deemed threats to state security, such cases are typically shrouded in opacity, making definitive conclusions difficult. For instance, the 2009 execution of ethnic Uyghur activist Tashpolat Tiyip on charges of "separatism" exemplifies the state’s harsh response to perceived dissent, though the exact number of such executions remains unverifiable due to restricted access to data.

In contrast, countries like Germany and Canada institutionalize dissent through robust legal protections. Germany’s *Grundgesetz* (Basic Law) explicitly safeguards freedom of expression, even for views critical of the government, while Canada’s *Charter of Rights and Freedoms* ensures citizens can protest without fear of retribution. These nations not only tolerate dissent but often integrate it into policy-making processes, viewing it as essential for democratic health. For activists operating in restrictive regimes, studying these frameworks can provide actionable strategies for advocating change within legal boundaries.

Authoritarian regimes outside China, such as Saudi Arabia and Belarus, employ similar tactics to suppress dissent, but with varying degrees of severity. Saudi Arabia’s 2019 mass execution of 37 citizens, including political protesters, underscores a pattern of lethal repression, whereas Belarus relies more on prolonged imprisonment and exile, as seen in the treatment of opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya. These differences highlight the importance of context: while execution remains a tool in some states, others prioritize less visible forms of control, such as surveillance or economic coercion.

For organizations monitoring human rights, a comparative analysis reveals gaps in global accountability mechanisms. The United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial executions often faces barriers in accessing data from closed societies, limiting their ability to intervene effectively. Meanwhile, grassroots initiatives like the *China Human Rights Defenders Network* leverage international pressure to spotlight individual cases, demonstrating the power of cross-border solidarity. Practical steps for advocates include documenting violations meticulously, leveraging international law frameworks like the *International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights*, and collaborating with diaspora communities to amplify voices from within repressive regimes.

Ultimately, the global variance in handling dissent underscores the tension between state sovereignty and universal rights. While democracies embed dissent into their governance structures, authoritarian regimes view it as an existential threat, often responding with extreme measures. For those navigating these landscapes, understanding these disparities is not just academic—it’s a survival guide. By adopting strategies from more open societies, such as leveraging international legal tools or building coalitions, activists can mitigate risks while advancing their causes, even in the face of oppressive systems.

Ethnicity as a Socio-Political Construct: Identity, Power, and Representation

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

China has a history of executing individuals for political dissent, though such cases are often classified as crimes like "subversion of state power" or "splitting the state." The exact number of executions is not publicly disclosed, but human rights organizations report that political dissidents, particularly those advocating for independence in regions like Tibet or Xinjiang, face severe punishment, including the death penalty.

The Chinese government justifies these actions by framing them as necessary to maintain social stability, national unity, and security. It often labels political dissent as threats to state sovereignty or attempts to overthrow the government, which are considered serious crimes under Chinese law.

Specific recent cases are difficult to confirm due to limited transparency, but notable examples include the execution of activists in Xinjiang and Tibet. For instance, in 2014, authorities executed eight people in Xinjiang for "terrorist attacks," though critics argue these were politically motivated charges.

Internationally, China’s treatment of political dissidents, including executions, has drawn widespread condemnation from human rights organizations, Western governments, and the United Nations. Critics argue that these actions violate international human rights norms and freedoms of speech and assembly. However, China often dismisses such criticism as interference in its internal affairs.