The question of whether a political party must nominate the incumbent candidate in an election is a nuanced and contentious issue that intersects with party dynamics, electoral strategy, and democratic principles. While incumbents often benefit from name recognition, experience, and access to resources, parties may weigh factors such as the incumbent's popularity, policy alignment, or the need for fresh leadership when deciding on nominations. In some cases, parties prioritize unity and avoid challenging incumbents to maintain stability, while in others, they may opt for new candidates to address voter dissatisfaction or adapt to shifting political landscapes. This decision-making process reflects the delicate balance between loyalty to established figures and the pursuit of electoral success, raising broader questions about the role of parties in representing voter interests and fostering competitive democracy.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Legal Requirement | No federal law in the U.S. mandates a party to nominate the incumbent. |

| Party Rules | Parties often prioritize incumbents in primaries due to internal rules. |

| Voter Preference | Incumbents typically have higher name recognition and resources. |

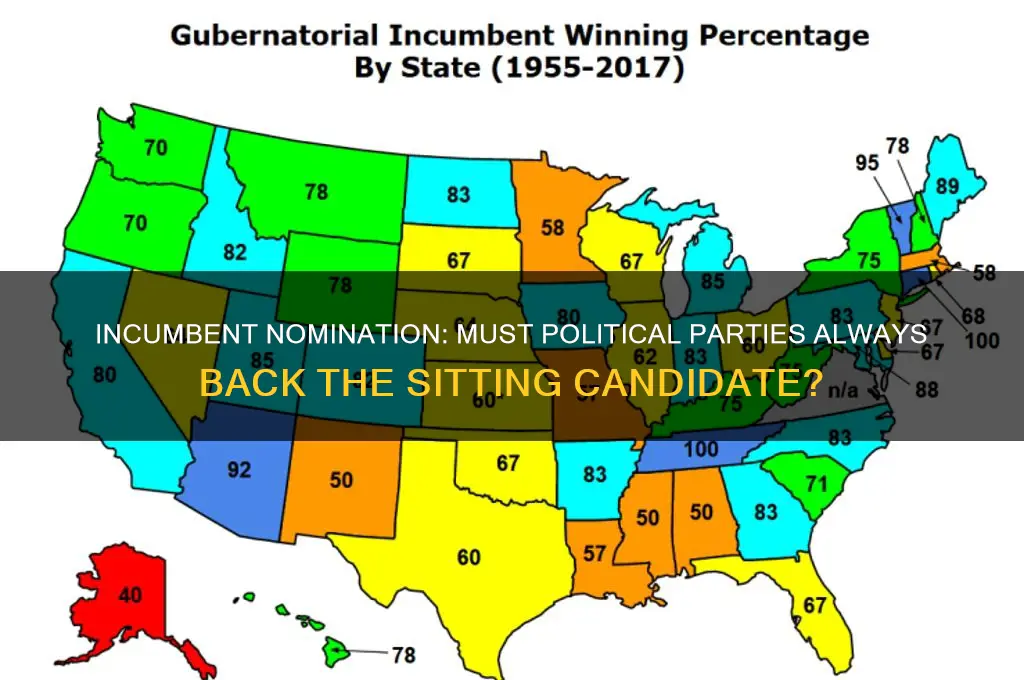

| Challenger Success Rate | Challengers rarely defeat incumbents in party primaries. |

| Historical Precedent | Incumbents are usually renominated unless embroiled in scandal or failure. |

| Strategic Advantage | Parties often back incumbents to maintain power and avoid division. |

| Exceptions | Rare cases occur due to extreme unpopularity or ideological shifts. |

| Primary Challenges | Incumbents may face primary challenges but usually prevail. |

| Party Loyalty | Parties tend to support incumbents to uphold unity and stability. |

| Resource Allocation | Incumbents receive more party funding and support than challengers. |

Explore related products

$0.99 $4.63

What You'll Learn

- Historical Precedents: Examines past elections where incumbents ran without party nomination

- Party Loyalty: Explores the role of party loyalty in nominating incumbents

- Primary Challenges: Discusses instances where incumbents faced primary challenges from within the party

- Independent Runs: Analyzes incumbents running as independents after losing party nomination

- Voter Perception: Investigates how voters view incumbents without official party backing

Historical Precedents: Examines past elections where incumbents ran without party nomination

In the annals of political history, there have been instances where incumbent candidates sought re-election without the official nomination of their party, challenging the conventional norms of electoral politics. These cases provide valuable insights into the dynamics between political parties and their leaders, often revealing the complexities of power struggles and ideological differences. One notable example is the 1912 United States presidential election, which showcased a dramatic split within the Republican Party. President William Howard Taft, the incumbent, was challenged by former President Theodore Roosevelt, who had grown dissatisfied with Taft's policies. Roosevelt's progressive agenda and charismatic appeal led him to seek the Republican nomination, but when Taft secured it, Roosevelt and his supporters bolted from the party. This resulted in Roosevelt running as the candidate for the newly formed Progressive Party, also known as the Bull Moose Party, while Taft remained the official Republican nominee. This election is a prime illustration of an incumbent president effectively running without his party's full support, as the Republican vote was split, ultimately leading to the victory of Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

Another intriguing case is the 1948 United States presidential election, where incumbent President Harry S. Truman faced significant opposition within his own Democratic Party. Truman's liberal policies and his support for civil rights alienated many Southern Democrats, who were more conservative. This faction, known as the Dixiecrats, broke away and formed the States' Rights Democratic Party, nominating South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond as their candidate. Despite this division, Truman chose to seek re-election as the Democratic nominee, effectively running without the unified support of his party. Truman's campaign strategy focused on appealing directly to the people, and he successfully portrayed himself as a decisive leader, ultimately winning the election against both Thurmond and the Republican nominee, Thomas E. Dewey.

In the United Kingdom, the 1846 general election presents an interesting scenario. The incumbent Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, found himself at odds with his Conservative Party over the issue of free trade. Peel's decision to repeal the Corn Laws, which imposed tariffs on imported grain, was deeply unpopular with many Conservatives, who favored protectionism. Despite being the sitting Prime Minister, Peel's actions led to a significant rebellion within his party. In the subsequent election, while Peel himself was re-elected in his constituency, the Conservatives lost their majority, and Peel's government fell. This event highlights how an incumbent leader's policy decisions can lead to a de facto lack of party support during an election.

These historical precedents demonstrate that while it is not a common occurrence, incumbents have run for re-election without their party's nomination due to various political circumstances. Such situations often arise from ideological conflicts, personal rivalries, or policy disagreements, leading to party divisions. In some cases, like Roosevelt's and Truman's, the incumbents chose to challenge their party's establishment, while in Peel's case, his policies caused a rift. These elections offer valuable lessons on the delicate balance of power between political leaders and the parties they represent, showing that incumbents can sometimes forge their path to re-election, even without the traditional party machinery behind them.

Are Political Parties Unconstitutional? Exploring Legal and Historical Perspectives

You may want to see also

Party Loyalty: Explores the role of party loyalty in nominating incumbents

Party loyalty plays a pivotal role in the nomination of incumbent candidates within political parties. At its core, party loyalty refers to the commitment of party members, leaders, and voters to support the party's chosen candidates, especially those already in office. This loyalty is often driven by a shared ideology, policy goals, and the desire to maintain or expand the party's influence in government. When it comes to incumbents, party loyalty frequently manifests as a strong inclination to renominate them, as they are seen as proven assets who have already demonstrated their ability to win elections and advance the party's agenda. This practice is not a formal requirement but is deeply ingrained in the political culture of many democracies, where parties prioritize stability and continuity over frequent changes in leadership.

The rationale behind party loyalty in nominating incumbents is multifaceted. Incumbents often bring significant advantages to the table, such as name recognition, established networks, and a track record of governance. These factors make them more likely to win reelection, reducing the risk of losing a seat to the opposing party. Additionally, incumbents typically have access to resources like campaign funding, staff, and institutional knowledge, which can streamline the election process for the party. Party leaders also value incumbents for their experience in navigating legislative processes and building coalitions, which are crucial for achieving policy objectives. Thus, renominating incumbents is often seen as a strategic decision to safeguard the party's interests and maximize its chances of success.

However, party loyalty to incumbents is not without its challenges. In some cases, incumbents may become unpopular due to scandals, policy failures, or shifting public sentiment. When this happens, the party faces a dilemma: whether to remain loyal to the incumbent or risk alienating voters by continuing to support them. Parties must balance loyalty with pragmatism, sometimes opting to replace incumbents with fresher candidates who better align with current voter preferences. This decision is often influenced by internal party dynamics, such as the strength of the incumbent's support within the party and the availability of viable alternatives. Despite these challenges, the default tendency remains to back incumbents, as parties are generally risk-averse and prefer the known quantity over the unknown.

Another critical aspect of party loyalty is its impact on intra-party competition. When incumbents are automatically favored for renomination, it can stifle opportunities for new candidates to emerge. This dynamic can lead to stagnation within the party, as fresh voices and perspectives are sidelined in favor of established figures. Critics argue that such loyalty undermines democratic principles by limiting voter choice and perpetuating the status quo. To address this, some parties have implemented mechanisms like open primaries or challenger-friendly rules, which allow greater competition for nominations. However, these reforms often face resistance from party elites who prioritize unity and stability over internal competition.

In conclusion, party loyalty is a central factor in the nomination of incumbents, driven by strategic, ideological, and practical considerations. While it offers parties the benefits of stability, experience, and reduced electoral risk, it also poses challenges related to accountability, innovation, and democratic representation. The tension between loyalty to incumbents and the need for renewal is a recurring theme in party politics, reflecting broader debates about how best to balance tradition and progress. Ultimately, the extent to which a party prioritizes loyalty to incumbents depends on its internal culture, external pressures, and the specific context of each election cycle. Understanding this dynamic is essential for grasping the complexities of candidate selection and the broader functioning of political parties in democratic systems.

Can You Only Vote in Your Political Party? Understanding Voting Rules

You may want to see also

Primary Challenges: Discusses instances where incumbents faced primary challenges from within the party

In the realm of politics, primary challenges against incumbent candidates from within their own party are not uncommon, and they often signify internal divisions or shifts in ideological stances. These challenges raise important questions about party loyalty, voter preferences, and the dynamics of political power. While a political party is not legally obligated to nominate the incumbent, the decision to support or replace a sitting candidate can have significant implications for the party's future and its relationship with the electorate. Primary challenges serve as a mechanism for parties to reevaluate their direction and for voters to express their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the current leadership.

One notable example of a primary challenge occurred in 2020 when Representative Eliot Engel, a long-serving Democratic incumbent from New York, faced a formidable challenge from Jamaal Bowman, a progressive educator. Bowman's campaign capitalized on Engel's perceived disconnect from his district and the growing appetite for progressive policies within the Democratic Party. Despite Engel's extensive experience and endorsements from establishment figures, Bowman secured the nomination, highlighting the power of grassroots movements and the shifting ideological landscape within the party. This case underscores how primary challenges can be a response to changing voter priorities and the incumbent's alignment with those priorities.

Another instance of a high-profile primary challenge took place in 2014 when Eric Cantor, then the House Majority Leader and a prominent Republican, lost his primary race to Dave Brat, a college professor and political newcomer. Brat's campaign focused on Cantor's support for immigration reform and his perceived closeness to the Washington establishment, which resonated with conservative voters in the district. Cantor's defeat was a stunning upset and demonstrated how incumbents can become vulnerable when they are perceived as out of touch with their party's base. This challenge also illustrated the risks incumbents face when their policy positions diverge from the core beliefs of their party's electorate.

Primary challenges are not limited to federal races; they also occur at the state and local levels. For example, in 2018, Cynthia Nixon, a progressive activist and actress, challenged New York Governor Andrew Cuomo in the Democratic primary. Nixon's campaign focused on issues like income inequality, education funding, and criminal justice reform, appealing to the party's left wing. Although Cuomo ultimately won the nomination, Nixon's challenge forced him to address progressive concerns more directly and highlighted the growing influence of the party's progressive faction. This example shows how primary challenges can push incumbents to adapt their platforms and engage with emerging issues within their party.

In some cases, primary challenges are driven by personal or ethical controversies surrounding the incumbent. For instance, in 2012, Senator Richard Lugar of Indiana faced a primary challenge from Richard Mourdock, a state treasurer who criticized Lugar for his bipartisanship and longevity in office. Mourdock's victory was fueled by Tea Party support and dissatisfaction with Lugar's moderate stances. This challenge reflected broader tensions within the Republican Party between its establishment and conservative wings. Such instances emphasize how primary challenges can be a tool for voters to hold incumbents accountable for their actions and policy decisions.

In conclusion, primary challenges against incumbents from within their own party are a critical aspect of the democratic process, allowing for internal accountability and reflection. These challenges often arise from ideological shifts, perceived disconnection from the party base, or personal controversies. While parties are not required to nominate incumbents, the decision to support or replace them can shape the party's identity and future electoral success. Through primary challenges, voters and party members assert their influence, ensuring that elected officials remain responsive to the evolving needs and values of their constituents.

Did the US Constitution Anticipate Political Parties?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Independent Runs: Analyzes incumbents running as independents after losing party nomination

In the realm of politics, the question of whether a political party must nominate an incumbent has significant implications, especially when incumbents decide to run as independents after losing their party's nomination. This scenario, though relatively rare, offers valuable insights into the dynamics between politicians, their parties, and the electorate. When an incumbent loses their party's nomination, it often signals a rift within the party, whether due to ideological differences, personal conflicts, or strategic disagreements. Running as an independent becomes a strategic move for these incumbents, allowing them to bypass party constraints and appeal directly to voters. However, this decision is not without risks, as it can alienate party loyalists and complicate fundraising and campaign infrastructure.

Independent runs by incumbents are often driven by a desire to maintain political relevance and power. Incumbents typically have name recognition, established networks, and a track record of governance, which can give them an edge over traditional independent candidates. However, losing the party nomination can strip them of crucial resources, such as funding, volunteer support, and access to party machinery. To succeed, these candidates must craft a compelling narrative that justifies their independent run, often framing it as a stand against party extremism or a commitment to constituent interests over partisan loyalty. This approach can resonate with voters disillusioned with party politics, but it requires careful messaging to avoid appearing opportunistic.

Analyzing the success of incumbents running as independents reveals mixed outcomes. Some candidates leverage their incumbency advantage to secure victory, particularly in districts or states where their personal brand transcends party lines. For example, cases like Senator Joe Lieberman in 2006 demonstrate how a well-known incumbent can win as an independent by capitalizing on local support and a moderate stance. Conversely, others struggle to overcome the loss of party backing, facing challenges in mobilizing resources and countering opposition from both their former party and the opposing party. The viability of an independent run often depends on the incumbent's ability to build a robust campaign structure independently and to appeal to a broad spectrum of voters beyond their former party base.

The decision to run as an independent also has broader implications for the political landscape. It can disrupt traditional party dynamics, forcing parties to reevaluate their nomination processes and strategies. For instance, a successful independent run might encourage parties to prioritize inclusivity and moderation to avoid alienating popular incumbents. Conversely, it can lead to more polarized party platforms as parties seek to consolidate their base. Additionally, independent runs by incumbents can influence electoral outcomes by splitting the vote, potentially benefiting the opposing party. This phenomenon underscores the importance of understanding voter behavior and the role of incumbency in shaping election results.

In conclusion, independent runs by incumbents who have lost their party's nomination represent a complex and high-stakes strategy in political campaigns. These candidates must navigate significant challenges, from resource constraints to voter perceptions, while leveraging their incumbency advantages. The success of such runs depends on a combination of factors, including the incumbent's personal brand, campaign strategy, and the political climate. For scholars and practitioners, studying these cases provides valuable lessons on the interplay between party politics, incumbency, and voter preferences. As the political landscape continues to evolve, the phenomenon of incumbents running as independents will remain a critical area of analysis in understanding modern electoral dynamics.

Can a New Political Party Reshape the Current Political Landscape?

You may want to see also

Voter Perception: Investigates how voters view incumbents without official party backing

Voter perception plays a critical role in shaping the electoral fortunes of incumbents who lack official party backing. When a political party chooses not to nominate an incumbent, voters often interpret this decision as a signal of internal discord or dissatisfaction within the party. This can lead to skepticism among the electorate, as voters may question the incumbent's effectiveness, loyalty, or alignment with the party's core values. Such perceptions can erode trust, even if the incumbent has a strong track record, as voters tend to associate party endorsement with legitimacy and reliability.

The absence of official party support can also create ambiguity in the minds of voters. Without a clear party endorsement, incumbents may struggle to communicate their platform effectively, leaving voters unsure of where they stand on key issues. This uncertainty can be particularly damaging in polarized political environments, where voters often rely on party labels as shortcuts to evaluate candidates. Incumbents without party backing may find themselves having to work harder to define their identity and differentiate themselves from both their own party and opponents, which can be a challenging and resource-intensive task.

Interestingly, some voters may view incumbents without party backing as independent thinkers or mavericks, willing to stand up to party establishment. This perception can be advantageous in certain contexts, particularly if there is widespread disillusionment with partisan politics. Such incumbents may appeal to moderate or independent voters who value bipartisanship and pragmatism over strict party loyalty. However, this positive perception is not guaranteed and depends heavily on the incumbent's ability to frame their lack of party support as a strength rather than a weakness.

Another factor influencing voter perception is the reason behind the party's decision to withhold support. If the incumbent is perceived as having been unfairly sidelined due to internal power struggles or ideological differences, voters may rally behind them as a symbol of resistance against party elites. Conversely, if the incumbent is seen as having lost party support due to scandal, ineffectiveness, or policy failures, voter perception is likely to be overwhelmingly negative. Transparency about the reasons for the lack of party backing can therefore significantly impact how voters interpret the situation.

Ultimately, incumbents without official party backing face a complex challenge in managing voter perception. They must navigate the delicate balance between distancing themselves from a party that has rejected them and maintaining credibility with the electorate. Successful incumbents in this position often leverage their personal brand, highlight their achievements, and focus on local issues to build a direct connection with voters. However, the absence of party infrastructure and resources can make this an uphill battle, underscoring the critical role party nomination plays in shaping voter attitudes and electoral outcomes.

Interest Groups vs. Political Parties: Which Holds More Power in Politics?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, a political party is not required to nominate the incumbent candidate. Parties typically hold primaries or caucuses where members vote to select their nominee, and incumbents can face challengers within their own party.

Yes, an incumbent can run for re-election as an independent or under a different party if they do not receive their original party's nomination. However, this is often more challenging due to reduced resources and party support.

A party might choose not to nominate an incumbent if the candidate is unpopular, embroiled in scandal, or out of alignment with the party's current platform. Parties often prioritize electability and ideological consistency when selecting nominees.