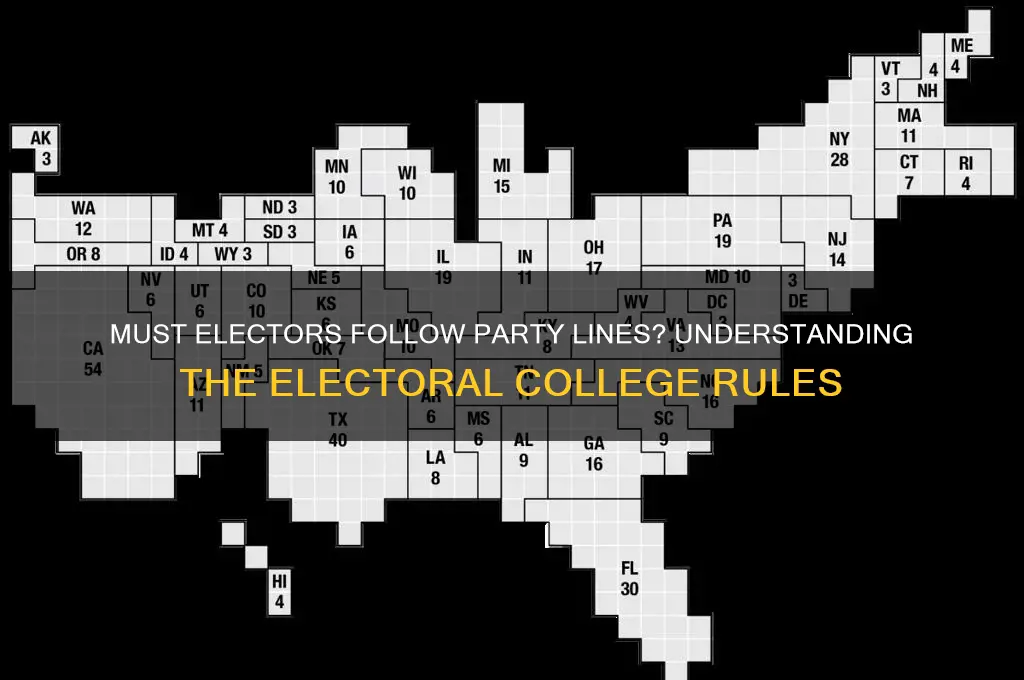

The question of whether electors in the U.S. Electoral College are required to vote according to their political party's nominee is a complex and often debated issue. While the majority of electors historically vote in line with their party's candidate, there is no federal law mandating this behavior, and state laws vary widely. Some states have implemented faithless elector laws, imposing penalties or replacing electors who deviate from their pledged vote, while others allow electors to vote freely. This system raises questions about the balance between party loyalty, individual discretion, and the democratic process, particularly in close or contentious elections. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for grasping the intricacies of the Electoral College and its role in American presidential elections.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Faithless Electors | In most states, electors are not legally bound to vote according to their party's nominee, though some states have laws requiring them to do so. |

| State Laws | 33 states and the District of Columbia have laws requiring electors to vote for their party's candidate, but enforcement varies. |

| Penalties for Faithless Electors | Penalties range from fines (e.g., $1,000 in Washington) to having their vote canceled and replaced by a substitute elector. |

| Impact on Elections | Faithless electors have rarely affected election outcomes; most elections are decided by large margins in the Electoral College. |

| Supreme Court Ruling (2020) | The Supreme Court ruled in Chiafalo v. Washington that states can bind electors to vote for their party's nominee. |

| Number of Faithless Electors (Historically) | Since the founding of the U.S., there have been 167 faithless electors, with the most recent occurring in 2016 (7) and 2020 (2). |

| Public Opinion | Polls show mixed opinions, but a majority of Americans support abolishing the Electoral College in favor of a popular vote system. |

| Constitutional Basis | The Constitution does not explicitly require electors to vote for their party's candidate, leaving room for state interpretation. |

| Political Party Influence | Parties typically vet electors to ensure loyalty, reducing the likelihood of faithless votes. |

| Historical Significance | The Electoral College system was designed to balance state and federal power, not to strictly enforce party loyalty. |

Explore related products

$14.22 $21.95

What You'll Learn

- Legal Obligations of Electors: Are electors legally bound to vote according to party affiliation or pledges

- Faithless Electors: Consequences and frequency of electors voting against their party’s nominee

- State Laws on Elector Voting: How state laws influence or restrict electors’ voting behavior

- Ethical vs. Party Loyalty: Balancing personal ethics with political party expectations in electoral votes

- Historical Precedents: Instances where electors defied party lines and their impact on elections

Legal Obligations of Electors: Are electors legally bound to vote according to party affiliation or pledges?

The role of electors in the United States Electoral College system often raises questions about their legal obligations, particularly whether they are bound to vote according to their political party affiliation or pledges. The answer to this question varies by state and is rooted in a combination of state laws, constitutional principles, and historical practices. While some states have laws that attempt to bind electors to vote for their party’s candidate, the legal enforceability of these laws remains a subject of debate and has been tested in court.

In most states, electors are chosen by political parties and are expected to vote for their party’s nominee. However, the legal obligation to do so is not uniform. As of recent data, 33 states and the District of Columbia have laws requiring electors to vote for their party’s candidate. These laws often include penalties for "faithless electors," such as fines or removal from their position. For example, in Washington State, a faithless elector can be fined $1,000, while in Colorado, an elector who violates their pledge can be replaced by a substitute elector. Despite these laws, the Supreme Court’s 2020 ruling in *Chiafalo v. Washington* upheld the power of states to enforce such penalties, affirming that states have the authority to bind electors to the popular vote winner.

However, the question of whether these laws are constitutionally sound remains complex. The Constitution does not explicitly require electors to vote according to popular vote or party pledges. Article II, Section 1, and the 12th Amendment grant electors the discretion to vote as they choose, which has led to arguments that state laws binding electors may violate the Constitution. Critics of these laws argue that they undermine the independent judgment of electors, a principle some believe was intended by the Founding Fathers. This tension between state laws and constitutional interpretation highlights the ambiguity surrounding the legal obligations of electors.

In practice, faithless electors are rare and have never changed the outcome of a presidential election. Between 1796 and 2016, there were only 165 faithless electors out of more than 23,000 total electoral votes cast. The increase in faithless electors in 2016 (seven) and 2020 (two) sparked renewed interest in this issue, but their impact was minimal. While state laws aim to deter such behavior, the constitutional question of whether electors can be compelled to vote against their conscience remains unresolved.

In conclusion, electors in most states are legally obligated to vote according to their party affiliation or pledges, as enforced by state laws. However, the constitutionality of these laws is still debated, and the Supreme Court’s ruling in *Chiafalo v. Washington* has provided some clarity but not settled all questions. Electors theoretically retain the discretion to vote independently, but doing so carries legal risks in many states. Understanding these legal obligations is crucial for grasping the intricacies of the Electoral College system and the role of electors in U.S. presidential elections.

Can Political Parties Legally Purchase Land? Exploring Ownership Rules

You may want to see also

Faithless Electors: Consequences and frequency of electors voting against their party’s nominee

In the United States, the Electoral College system plays a pivotal role in determining the outcome of presidential elections. Electors, who are typically chosen by political parties, are expected to vote for their party's nominee. However, there have been instances where electors have voted against their party's candidate, earning the title of "faithless electors." The question of whether electors are legally bound to vote according to their party’s nominee varies by state. While some states have laws requiring electors to vote for their party's candidate, others do not impose such restrictions. Despite these laws, the consequences for faithless electors are often minimal, typically limited to fines or removal from their position, with no historical instance of a faithless elector's vote being invalidated.

The frequency of faithless electors is relatively rare, given the strong party loyalty and norms that govern the Electoral College process. Since the founding of the United States, there have been only 167 instances of faithless electors out of more than 23,000 electoral votes cast. The majority of these instances occurred in the early years of the nation when party discipline was less rigid. In modern times, faithless votes are even rarer, with only a handful occurring in recent decades. For example, in the 2016 election, there were seven faithless electors, the highest number in over a century, but their votes did not alter the election outcome. This rarity underscores the stability of the Electoral College system and the strong adherence to party loyalty among electors.

The consequences of faithless electors voting against their party’s nominee are primarily symbolic rather than substantive. While such actions can draw significant media attention and spark debates about the role of electors, they rarely impact the election result. The 2020 election saw no faithless electors, reflecting the heightened polarization and party discipline of the current political climate. However, the potential for faithless electors to influence close elections remains a theoretical concern. Critics argue that faithless electors undermine the will of the voters, while proponents view their actions as a check on the Electoral College system, allowing electors to exercise independent judgment in extreme circumstances.

Legal challenges to faithless electors have further clarified their role and limitations. In 2020, the Supreme Court ruled in *Chiafalo v. Washington* that states can enforce laws requiring electors to vote for their party’s nominee, effectively upholding the ability of states to punish or replace faithless electors. This decision reinforced the principle that electors are not entirely free agents but are bound by state laws and party commitments. Despite this ruling, the practical impact of faithless electors remains limited, as their votes have never changed the outcome of a presidential election.

In conclusion, while faithless electors are a fascinating aspect of the U.S. electoral system, their frequency and impact are minimal. The rarity of such occurrences, combined with legal constraints and strong party loyalty, ensures that the Electoral College process remains largely predictable. Debates about the role and responsibility of electors continue, but for now, faithless electors remain an uncommon and largely symbolic phenomenon in American presidential elections.

BC Political Donations: Can Corporations Legally Support Parties?

You may want to see also

State Laws on Elector Voting: How state laws influence or restrict electors’ voting behavior

In the United States, the role of electors in the Electoral College is a critical component of the presidential election process. While the general assumption is that electors vote according to the popular vote in their state, the reality is more nuanced, and state laws play a significant role in influencing or restricting their voting behavior. These laws vary widely, creating a patchwork of regulations that can either bind electors to the will of the voters or grant them a degree of independence.

Binding Laws and Penalties

Many states have enacted laws that require electors to cast their votes in accordance with the popular vote in their state. These are known as "binding laws." For instance, 33 states and the District of Columbia have laws that mandate electors to vote for the presidential and vice-presidential candidates who won the state’s popular vote. In some states, such as California and New York, electors who fail to comply with these laws can be subject to penalties, including fines or even replacement by an alternate elector. These laws are designed to ensure that the electors reflect the will of the state’s voters and minimize the risk of "faithless electors."

Pledge Systems and Political Party Influence

In addition to binding laws, many states require electors to sign a pledge, often through their political party, committing to vote for the party’s nominated candidates. This practice is widespread and reinforces the expectation that electors will align with their party’s ticket. While not all states enforce these pledges legally, the political and social pressure to adhere to them is significant. For example, in states without binding laws, such as Virginia and Georgia, electors are still expected to honor their pledges, and deviations can lead to censure or expulsion from the party.

Freedom for Faithless Electors

Conversely, some states do not restrict electors’ voting behavior, allowing them to vote their conscience. States like Maine and Vermont have no laws binding electors to the popular vote, granting them the freedom to act as independent agents. This has led to instances of "faithless electors," who vote contrary to the popular vote. While rare, these occurrences highlight the potential for electors to exercise personal judgment, particularly in states without binding laws or penalties.

Legal Challenges and Supreme Court Rulings

The issue of elector independence has been the subject of legal challenges, culminating in the 2020 Supreme Court case *Chiafalo v. Washington*. The Court ruled unanimously that states have the constitutional authority to bind electors and enforce penalties for faithless voting. This decision reinforced the power of state laws in shaping elector behavior and underscored the importance of state-level regulations in maintaining the integrity of the Electoral College system.

Implications for Electoral Integrity

State laws on elector voting are pivotal in balancing the principles of democracy and the role of electors. Binding laws ensure that the popular vote is respected, while the absence of such laws preserves a degree of elector autonomy. As the Electoral College continues to evolve, state legislatures will remain at the forefront of shaping how electors fulfill their duties, reflecting the diverse political landscapes and priorities of each state. Understanding these laws is essential for comprehending the mechanics of presidential elections and the potential for variation in elector behavior.

Are Political Parties Truly Addressing Our Concerns? A Critical Analysis

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Ethical vs. Party Loyalty: Balancing personal ethics with political party expectations in electoral votes

In the United States, the role of electors in the Electoral College system often sparks debates about the tension between personal ethics and party loyalty. Electors are typically chosen by political parties and are expected to vote in accordance with the popular vote of their state, reflecting the party's nominee. However, the question of whether electors are legally bound to vote according to their party’s expectations varies by state. Some states have laws requiring electors to cast their votes for the party’s candidate, while others do not. This legal framework sets the stage for the ethical dilemma electors may face: should they prioritize their personal moral convictions or adhere to party expectations?

Ethical considerations come to the forefront when electors confront situations where their party’s nominee conflicts with their own values or principles. For instance, an elector might believe that a candidate is unfit for office due to ethical concerns, such as corruption, incompetence, or policy positions that contradict their moral beliefs. In such cases, voting against the party’s nominee could be seen as an act of conscience, upholding personal integrity and the broader public interest. However, this decision often carries significant consequences, including potential legal penalties, backlash from the party, and public scrutiny. The challenge lies in weighing the importance of individual ethics against the commitment to party loyalty and the democratic process.

On the other hand, party loyalty plays a crucial role in maintaining the stability and predictability of the electoral system. Electors are often selected based on their dedication to the party, and their votes are expected to reflect the will of the voters who supported the party’s candidate. Deviating from this expectation can undermine the legitimacy of the election and erode trust in the political process. Additionally, party loyalty fosters unity and ensures that the collective efforts of party members are not undermined by individual dissent. For many electors, honoring this commitment is a matter of principle, even if it means setting aside personal reservations.

Balancing ethical convictions with party loyalty requires careful deliberation and a nuanced understanding of the elector’s role. Electors must consider the potential impact of their vote on both the immediate election and the long-term health of the democratic system. Some argue that the duty of an elector is to act as a safeguard, ensuring that only qualified and ethical candidates ascend to office. Others contend that electors should serve as a conduit for the voters’ will, regardless of personal opinions. Striking this balance often involves introspection, consultation with trusted advisors, and a deep commitment to the principles of democracy.

Ultimately, the tension between ethical responsibility and party loyalty highlights the complexities of the Electoral College system. While some electors may feel compelled to prioritize their conscience, others may view their role as a fiduciary duty to the party and its voters. This debate underscores the need for clarity in laws governing electors’ obligations and a broader conversation about the purpose and function of the Electoral College in modern democracy. As the system evolves, so too will the expectations and ethical considerations faced by those entrusted with casting these critical votes.

Can You Spot Political Affiliations in People's Everyday Behavior?

You may want to see also

Historical Precedents: Instances where electors defied party lines and their impact on elections

In the United States, the Electoral College system has occasionally seen instances where electors defied their party’s nominee, casting votes contrary to the popular vote in their state. These "faithless electors" have historically been rare but have sparked significant debate about the role and obligations of electors. One notable example occurred in the 1836 election, when 23 Virginia electors refused to vote for Richard Mentor Johnson, the Democratic vice-presidential nominee, due to his relationship with a former enslaved woman. This defection forced the Senate to elect Johnson as vice president, the only time this has happened in U.S. history. While this instance did not alter the presidential outcome, it highlighted the potential for electors to act independently of their party.

Another significant case of faithless electors arose in the 1960 election, when an Alabama elector pledged to Democratic candidate John F. Kennedy instead voted for Harry F. Byrd, a conservative Democrat, as a protest against Kennedy's liberal policies. This defection was part of a larger effort by Southern electors to oppose Kennedy, though it did not affect the overall election result. Similarly, in the 1972 election, a Virginia elector pledged to Republican Richard Nixon voted for Libertarian candidate John Hospers, becoming the first elector to cast a vote for a third-party candidate in the 20th century. These instances underscore the autonomy some electors have exercised, even if their actions rarely change election outcomes.

The 2000 election saw a faithless elector in the District of Columbia, who cast a blank ballot to protest the district's lack of voting representation in Congress. While this did not impact the election, it drew attention to the broader issue of electoral reform. More recently, the 2016 election witnessed the largest number of faithless electors in modern history, with seven electors casting votes for candidates other than their pledged nominees. For instance, three Washington state electors voted for Colin Powell instead of Hillary Clinton, while a Texas elector voted for John Kasich instead of Donald Trump. Despite these defections, the election results remained unchanged, but the event reignited debates about the role of electors and the need for stricter enforcement of party loyalty.

The impact of faithless electors on elections has generally been minimal, as their numbers have never been sufficient to alter the outcome of a presidential race. However, their actions have raised constitutional and ethical questions about the Electoral College system. Some states have implemented laws to bind electors to their party’s nominee, with penalties for defection, but the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of such laws in the 2020 case Chiafalo v. Washington. Historically, these instances serve as reminders that electors, while typically party loyalists, are not legally bound in all states and can exercise independent judgment, even if such actions rarely sway election results.

In summary, historical precedents of faithless electors demonstrate that while such instances are rare, they have occurred across different eras and for various reasons. From the 1836 election to the 2016 election, these defections have highlighted the tension between party loyalty and individual elector autonomy. While their impact on election outcomes has been negligible, they have played a crucial role in shaping discussions about electoral reform and the future of the Electoral College system. Understanding these instances provides valuable insight into the complexities of the U.S. electoral process and the ongoing debate over the role of electors in American democracy.

Can a Sitting POTUS Abandon Their Political Party Mid-Term?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, electors are not legally required to vote according to their political party's nominee in all states, though some states have laws or pledges to encourage party loyalty.

Yes, electors can vote for someone other than their party's candidate, and these are known as "faithless electors," though some states impose penalties for doing so.

Yes, in some states, faithless electors may face penalties such as fines or removal from their position, but the specifics vary by state.