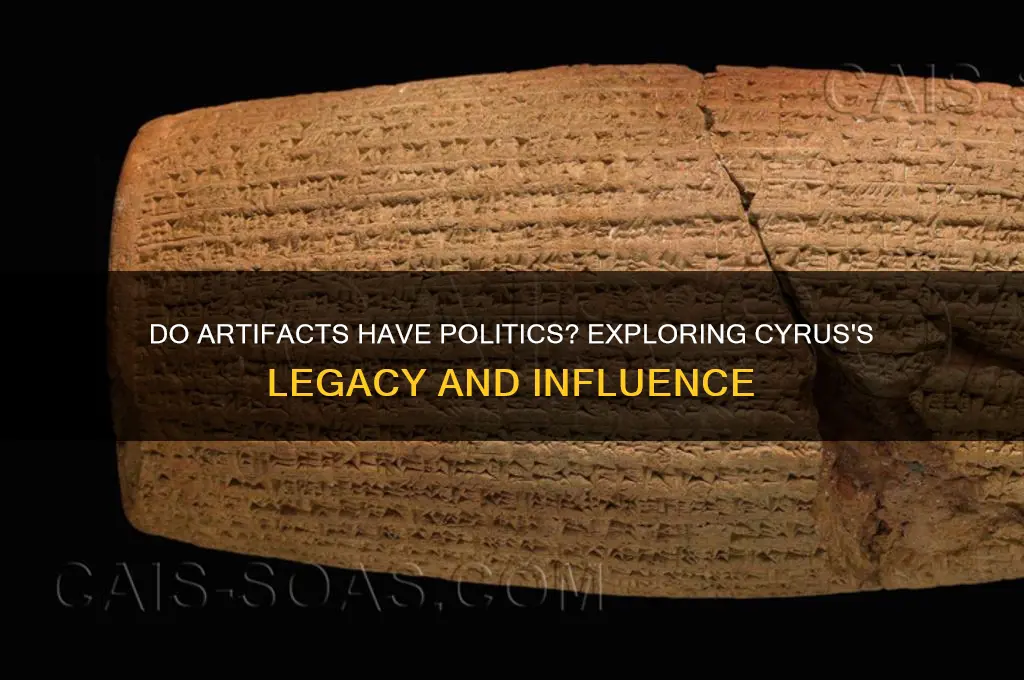

The question Do artifacts have politics? is a provocative concept introduced by Langdon Winner in his influential essay, which explores the inherent political dimensions embedded within technological designs. When considering this idea in the context of Cyrus, a figure often associated with historical artifacts and technological advancements of his era, it becomes intriguing to examine how the tools, structures, and innovations of his time might reflect or shape political ideologies. Cyrus, as a leader known for his administrative and military innovations, likely interacted with artifacts that were not merely neutral instruments but carried implicit values and power dynamics. From the design of his communication systems to the construction of roads and fortifications, these artifacts could have reinforced hierarchies, facilitated control, or even challenged existing norms, thereby illustrating how technology is never apolitical but rather a reflection of the societal and political contexts in which it is created and used.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Author | Langdon Winner |

| Title | Do Artifacts Have Politics? |

| Publication Year | 1980 |

| Type | Essay |

| Main Argument | Artifacts (technologies, structures, etc.) embody political values and can reinforce or challenge existing power structures. |

| Key Concepts | 1. Inherent Politics: Artifacts can have political implications by their design or function. 2. Social Shaping of Technology: Technologies are shaped by social and political contexts. 3. Technological Determinism Critique: Rejects the idea that technology is neutral or solely determines societal outcomes. |

| Examples Discussed | 1. Robert Moses' Bridges: Low clearance bridges in New York that prevented buses (used by poorer communities) from accessing parks. 2. Nuclear Power Plants: Centralized control vs. decentralized energy systems. |

| Influence | Widely cited in Science and Technology Studies (STS), design theory, and political philosophy. |

| Criticisms | 1. Overemphasis on intentionality in design. 2. Difficulty in distinguishing inherent politics from contextual use. |

| Relevance Today | Applies to modern technologies like AI, surveillance systems, and urban infrastructure, highlighting their political implications. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Design reflects values: Artifacts embody societal norms, biases, and power structures through their design choices

- Technology as ideology: Tools and systems often promote specific political or economic ideologies

- User control vs. autonomy: Artifacts can empower or restrict users, shaping their agency

- Environmental impact: The politics of resource use and ecological consequences in artifact production

- Accessibility and equity: Design choices determine who can access and benefit from artifacts

Design reflects values: Artifacts embody societal norms, biases, and power structures through their design choices

The design of everyday objects is never neutral. Consider the height of a doorknob. Placed at 36 inches, it accommodates the average adult, but excludes children and wheelchair users. This seemingly mundane decision embeds assumptions about who belongs in a space and who doesn’t. Artifacts, from doorknobs to algorithms, are not just tools; they are carriers of the values, biases, and power dynamics of the societies that create them.

Take the example of voice recognition technology. Studies show that systems like Siri and Alexa have higher accuracy rates for male voices than female voices, a bias rooted in the predominantly male datasets used during training. This design choice perpetuates gender inequality by making the technology less accessible to women. Similarly, facial recognition software often misidentifies people of color at higher rates than white individuals, reflecting the racial biases present in the data used to train these systems. These are not mere technical flaws but manifestations of systemic biases baked into the design process.

To uncover the politics of an artifact, ask: Who benefits from this design? Who is excluded? Take the layout of urban spaces. Wide sidewalks and accessible public transportation reflect a commitment to inclusivity, while car-centric cities prioritize speed and efficiency, often at the expense of pedestrians and cyclists. These choices are not accidental; they reflect societal priorities and power structures. For instance, the placement of public benches in shaded areas versus exposed spaces can signal whether a city values the comfort of all residents or prioritizes aesthetics over functionality.

Designers and consumers alike must recognize their role in this process. A practical tip: When evaluating a product, consider its lifecycle. Who made it? What materials were used? How will it be disposed of? For example, single-use plastics embody a culture of convenience and disposability, while reusable products reflect a commitment to sustainability. By asking these questions, we can challenge the status quo and advocate for designs that align with more equitable and just values.

Ultimately, artifacts are not passive objects but active participants in shaping our world. Their design choices—whether intentional or not—reinforce or challenge societal norms. By critically examining these choices, we can begin to dismantle harmful biases and create artifacts that serve everyone, not just the privileged few. Design is not just about aesthetics or functionality; it is a political act with far-reaching consequences.

Why Politics is Surprisingly Fun: Unraveling the Drama and Intrigue

You may want to see also

Technology as ideology: Tools and systems often promote specific political or economic ideologies

Artifacts, from the design of a city grid to the algorithms of social media, are not neutral. They embody the values, assumptions, and power structures of their creators. Consider the automobile: its dominance in urban planning reflects a mid-20th century ideology prioritizing individual mobility over communal space, fossil fuels over sustainability, and suburban sprawl over dense, walkable neighborhoods. This isn't an accident of engineering; it's a political choice baked into the very infrastructure of our cities.

Every tool, system, or technology carries within it a set of implicit instructions about how to live, work, and interact. The assembly line, for instance, wasn't just a more efficient way to build cars; it was a blueprint for a society organized around standardized tasks, hierarchical control, and the commodification of labor. Its success wasn't merely technical but ideological, reshaping not just production but the very concept of work itself.

Take the example of facial recognition technology. Its development and deployment are often framed as apolitical advancements in security. Yet, its use disproportionately targets marginalized communities, reinforcing existing biases and power imbalances. The technology itself becomes a tool of surveillance and control, reflecting and amplifying a particular political ideology that prioritizes order over freedom, suspicion over trust.

Recognizing the ideological underpinnings of technology is crucial for understanding its impact. It's not enough to ask "does it work?" We must also ask "for whom does it work?" and "at what cost?" A technology that benefits one group may marginalize another, perpetuating inequality and injustice.

This isn't to say all technology is inherently oppressive. We can design tools and systems that challenge dominant ideologies and promote alternative visions of society. Open-source software, for example, embodies a philosophy of collaboration and shared ownership, countering the proprietary model of corporate control. By understanding the ideological dimensions of technology, we can make more informed choices about the kind of world we want to build, and the tools we use to build it.

Does Political Ignorance Threaten Democracy and Civic Engagement?

You may want to see also

User control vs. autonomy: Artifacts can empower or restrict users, shaping their agency

Artifacts, from the design of a smartphone to the layout of a city, inherently shape how users interact with their environment. Consider the smartphone: its interface, notifications, and default settings dictate not just how we use it, but how often and for what purpose. A device designed for constant engagement—through addictive algorithms or intrusive notifications—restricts user autonomy by hijacking attention, while one with customizable settings and digital wellbeing tools empowers users to control their time and focus. This tension between control and autonomy highlights how artifacts embed political choices, often invisibly, into daily life.

To illustrate, examine the design of public transportation systems. A bus route planned without input from the communities it serves can restrict mobility for marginalized groups, reinforcing existing inequalities. Conversely, a system co-designed with users—incorporating flexible schedules, accessible stops, and affordable fares—empowers individuals by expanding their agency to move freely. The artifact here isn’t just the bus itself, but the entire system, including its governance and infrastructure. Such examples underscore that artifacts don’t merely reflect politics; they actively produce it by structuring possibilities for action.

Empowering users through artifact design requires intentionality. For instance, open-source software like Linux grants users full control over their digital environment, allowing them to modify code, prioritize privacy, and avoid vendor lock-ins. In contrast, proprietary software often restricts autonomy through licensing agreements, data harvesting, and limited customization. Designers and engineers must ask: Whose interests does this artifact serve? Does it foster dependency or independence? Answering these questions demands a shift from viewing artifacts as neutral tools to recognizing them as political actors in their own right.

Practical steps can bridge the gap between control and autonomy. For product designers, this might mean incorporating user feedback loops, offering transparency in data usage, or providing modular designs that adapt to diverse needs. For policymakers, it could involve mandating accessibility standards or regulating algorithms that manipulate behavior. Users, too, can reclaim agency by demanding ethical design, supporting open-source alternatives, and advocating for policies that prioritize human-centered innovation. The goal isn’t to eliminate artifacts’ influence but to ensure they enhance, rather than diminish, individual and collective autonomy.

Ultimately, the politics of artifacts lies in their ability to either amplify or suppress human agency. A wheelchair ramp, for example, isn’t just a physical structure; it’s a statement about inclusivity and the right to access public spaces. Similarly, a social media platform’s algorithm isn’t merely a technical feature; it’s a decision about whose voices are amplified and whose are silenced. By critically examining how artifacts shape control and autonomy, we can design a world where technology serves as a tool for empowerment, not a force of restriction. The choice, as always, is ours.

Did Christ Ignore Politics? Exploring His Stance on Governance and Power

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental impact: The politics of resource use and ecological consequences in artifact production

Artifacts, from smartphones to skyscrapers, are not politically neutral. Their creation and use are deeply entangled in resource extraction, manufacturing processes, and disposal methods that carry significant ecological consequences. Consider the rare earth minerals in your phone: mining these materials often involves habitat destruction, water pollution, and the displacement of communities. The politics of resource use here is stark—who benefits from these minerals, and who bears the environmental cost? This question underscores the inherent political nature of artifacts, revealing how their production perpetuates global inequalities and ecological degradation.

To mitigate the environmental impact of artifact production, a systemic shift is required. Manufacturers must adopt circular economy principles, prioritizing recycling, reuse, and sustainable sourcing. For instance, the fashion industry, responsible for 10% of global carbon emissions, could reduce its footprint by extending garment lifespans and using organic materials. Consumers, too, play a role by demanding transparency and supporting brands that prioritize sustainability. Governments can enforce stricter regulations on emissions and waste, incentivizing green practices. These steps, while challenging, are essential to decoupling artifact production from environmental harm.

A comparative analysis of two industries—automotive and electronics—highlights the politics of resource use. Electric vehicles (EVs) are often touted as eco-friendly, yet their production relies on lithium and cobalt, mined in environmentally and socially contentious conditions. Similarly, the tech industry’s demand for semiconductors drives water-intensive manufacturing, straining local ecosystems. Both cases illustrate how the "green" narrative of artifacts often masks their ecological and political complexities. Addressing these issues requires not just technological innovation but also ethical supply chain practices and global cooperation.

Finally, the ecological consequences of artifact production extend beyond immediate resource depletion to long-term environmental degradation. Microplastics from synthetic textiles, for example, infiltrate water systems, harming marine life and entering the food chain. Similarly, e-waste, often dumped in developing countries, releases toxic chemicals like lead and mercury, posing health risks to local populations. These examples demonstrate how artifacts’ lifecycles are deeply political, reflecting decisions about where and how waste is managed. By acknowledging these impacts, we can advocate for policies that prioritize ecological justice and hold industries accountable for their environmental footprints.

Exploring Moderate Political Magazines: Do They Exist in Today's Media Landscape?

You may want to see also

Accessibility and equity: Design choices determine who can access and benefit from artifacts

Design choices are not neutral. Every curve, material, and interface embeds assumptions about who will use an artifact and how. Consider the height of a doorknob: placed at 36 inches, it accommodates average adults but excludes children and wheelchair users. This simple decision, often overlooked, illustrates how design can either include or exclude. Accessibility, therefore, is not an afterthought but a political act, shaping who participates in society and who is left behind.

Take the example of public transportation. A bus with a single high step and narrow doors effectively bars wheelchair users, parents with strollers, and the elderly from boarding. Contrast this with low-floor buses equipped with ramps or kneeling features, which democratize mobility. The choice between these designs is not merely technical but ideological, reflecting societal priorities. When cities invest in accessible transit, they signal a commitment to equity, ensuring that all citizens can navigate their environment with dignity.

In the digital realm, the stakes are equally high. Websites and apps that ignore accessibility standards—such as alt text for images, keyboard navigation, and color contrast ratios—alienate users with disabilities. For instance, a visually impaired user relying on a screen reader cannot engage with a site lacking alt text, effectively locking them out of information or services. Designers must adhere to WCAG 2.1 guidelines, ensuring that digital artifacts are perceivable, operable, understandable, and robust for all users. This is not just good practice; it is a moral imperative in an increasingly online world.

However, accessibility is not solely about compliance; it is about innovation. Universal design principles, which aim to create products usable by all people without adaptation, often lead to breakthroughs. The curb cut, originally designed for wheelchair users, now benefits cyclists, parents with strollers, and delivery workers. Similarly, closed captioning, developed for the deaf community, has become indispensable for viewers in noisy environments or learning a new language. These examples demonstrate that designing for the margins often enhances the experience for everyone.

To embed equity into design, start with inclusive research. Engage diverse users early in the process, ensuring their needs inform every decision. For physical artifacts, test prototypes with individuals of varying abilities, ages, and body types. For digital products, conduct usability tests with screen readers and keyboard-only navigation. Additionally, adopt a "nothing about us without us" mindset, involving marginalized communities as co-creators rather than afterthoughts. Finally, advocate for policies that mandate accessibility, recognizing that design choices are not just technical but deeply political, shaping who belongs and who is excluded.

Mastering the Basics: A Beginner's Guide to Understanding Politics

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The main argument is that technological artifacts (objects and systems) are not neutral but embody political values and ideologies, influencing social structures and power dynamics.

Cyrus is not directly mentioned in the essay. The question likely refers to a misinterpretation or misattribution, as the essay focuses on technology and politics, not a specific person named Cyrus.

Winner uses examples like the low clearance of bridges on Long Island parkways (designed to exclude buses and certain groups) and the Robert Moses Parkway system to show how artifacts reflect political intentions.

The essay challenges the notion that technology is neutral by arguing that artifacts are shaped by the values, biases, and goals of their creators, and they, in turn, shape society in politically significant ways.