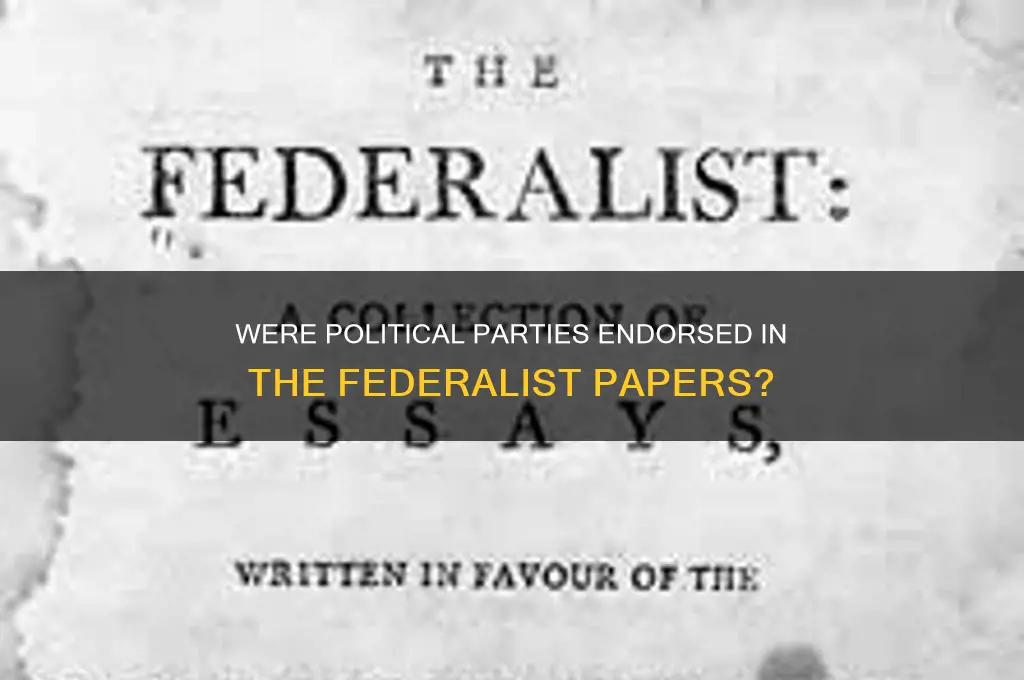

The Federalist Papers, a collection of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, primarily aimed to advocate for the ratification of the United States Constitution. While the essays address various aspects of governance, the topic of political parties is notably absent from their direct focus. At the time of their writing, political parties as we understand them today were not yet fully formed, and the authors generally viewed factions—which they defined as groups driven by self-interest—as a threat to the stability of the republic. In Federalist No. 10, James Madison famously argued that factions were inevitable and proposed a large, diverse republic as the best means to control their negative effects. However, the Papers do not explicitly endorse political parties as a positive force; instead, they emphasize the importance of a unified national government and the dangers of divisive factionalism. Thus, while the Federalist Papers laid the groundwork for understanding the challenges of faction, they did not explicitly support political parties as a beneficial aspect of governance.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| View on Political Parties | The Federalist Papers, particularly Federalist No. 10, did not explicitly state that political parties were "good." Instead, they warned about the dangers of factions, which they defined as groups driven by self-interest at the expense of the common good. |

| Factions vs. Parties | While not directly addressing political parties, the Papers equated factions with negative, divisive groups. Modern political parties, however, are seen as more structured and institutionalized, though they can still exhibit factional behavior. |

| Madison's Argument | James Madison argued that eliminating factions was impossible, so the goal should be to control their effects through a large, diverse republic where competing interests would balance each other. |

| Implicit Stance | The Papers implicitly suggest that while factions (including what we now call political parties) are inevitable, they are not inherently "good" and must be managed to prevent tyranny of the majority. |

| Modern Interpretation | Today, political parties are viewed as necessary for organizing political competition, mobilizing voters, and structuring governance, despite their potential for division. |

| Historical Context | At the time of the Federalist Papers, political parties were not yet fully formed in the U.S., so the focus was on factions rather than parties as we understand them today. |

| Balancing Interests | The Papers emphasized the importance of a system that balances competing interests, which aligns with the role of modern political parties in representing diverse viewpoints. |

| Conclusion | While the Federalist Papers did not endorse political parties as "good," they laid the groundwork for understanding how competing groups, including parties, could function within a democratic system. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Federalist Papers' View on Factions

The Federalist Papers, a collection of 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, primarily aimed to advocate for the ratification of the United States Constitution. Among the many topics addressed, the issue of factions—which can be seen as precursors to modern political parties—was a significant concern. In Federalist No. 10, James Madison directly tackles the problem of factions, defining them as groups of citizens united by a common interest or passion adverse to the rights of others or the interests of the whole community. Madison argues that factions are inevitable in a free society due to the nature of human beings, who will always form groups based on differing opinions and interests.

Madison’s view on factions is nuanced. While he acknowledges their potential for harm, such as infringing on the rights of others or destabilizing the government, he does not outright condemn them. Instead, he distinguishes between the causes and effects of factions. He identifies two ways to address the issue: removing the causes of faction or controlling their effects. Removing the causes, Madison argues, would require either destroying liberty—which is unacceptable in a free society—or giving every citizen the same opinions, passions, and interests, which is impossible. Therefore, Madison concludes that the only solution is to control the effects of factions.

To control the effects of factions, Madison advocates for a large, diverse republic. In a smaller political system, factions are more likely to dominate and oppress the minority. However, in a larger republic, the multitude of interests and factions makes it difficult for any single group to gain unchecked power. This diffusion of power, Madison argues, protects against tyranny and ensures that the majority’s will is more likely to align with the common good. Thus, while factions themselves are not inherently good, the structure of a large republic can mitigate their negative effects.

The Federalist Papers do not explicitly endorse political parties as we understand them today, as the modern party system did not yet exist during their writing. However, Madison’s analysis of factions can be interpreted as a pragmatic acceptance of their inevitability and a focus on managing their impact. His emphasis on the benefits of a large, representative government suggests that while factions (or political parties) may not be inherently desirable, they can be accommodated within a well-structured constitutional framework. This perspective aligns with the broader theme of the Federalist Papers, which seeks to create a stable and effective government capable of balancing competing interests.

In summary, the Federalist Papers, particularly Federalist No. 10, do not portray factions or political parties as inherently good. Instead, they recognize factions as a natural and unavoidable aspect of human society. Madison’s solution lies in the design of the government itself, advocating for a large republic that can dilute the power of factions and protect the rights of all citizens. This approach reflects a realistic and strategic view of political organization, prioritizing stability and the common good over the elimination of differing interests.

Are Political Parties Modern Dictatorships in Disguise?

You may want to see also

Madison's Argument Against Parties

James Madison, one of the principal authors of the Federalist Papers, presented a nuanced and critical view of political parties in Federalist No. 10. While the primary focus of this essay was the issue of factions, Madison's arguments indirectly addressed the dangers of political parties, which he saw as a subset of the broader problem of factions. Madison defined factions as groups of people united by a common interest or passion adverse to the rights of others or the interests of the community as a whole. He believed that the formation of such groups was inevitable in a free society due to the natural diversity of human opinions and interests.

A key aspect of Madison's argument is his belief in the importance of a unified, deliberative legislative process. He argued that a well-structured government should be capable of refining and enlarging the public views, ensuring that the voices of the majority are heard while also protecting the rights of minorities. However, Madison contended that political parties would distort this process by encouraging legislators to vote along party lines rather than engaging in thoughtful, independent decision-making. This would result in a loss of the very benefits that a representative government is designed to provide.

Madison also expressed concern about the potential for parties to manipulate public opinion and exploit the passions of the people. He believed that party leaders might use rhetoric and propaganda to sway voters, often at the expense of reasoned debate and informed decision-making. In Federalist No. 10, he warns against the "tyranny of the majority," but he also recognized the danger of a minority faction, such as a political party, gaining disproportionate control over the government. This would undermine the principles of equality and justice that are fundamental to a democratic society.

Lastly, Madison's argument against parties is rooted in his vision of a republic where citizens are actively engaged in the political process, informed, and capable of making decisions for the common good. He believed that political parties would create a professional political class, disconnected from the people, and focused on maintaining power rather than serving the public interest. By contrast, Madison advocated for a system where elected officials are directly accountable to their constituents, free from the influence of party loyalties. This, he argued, would foster a more virtuous and effective government, aligned with the principles of the Constitution.

In conclusion, Madison's argument against political parties in the Federalist Papers is a cautionary tale about the potential dangers of factionalism and partisanship. He believed that while factions are inevitable, their negative effects could be mitigated through a well-designed government that encourages deliberation, protects minority rights, and promotes the common good. By warning against the perils of parties, Madison sought to create a political system that would endure, ensuring the stability and prosperity of the nation. His insights remain relevant today, as the challenges posed by political polarization and partisanship continue to test the foundations of democratic governance.

Should Political Party Affiliation Influence Hiring Decisions? Ethical Considerations

You may want to see also

Unity vs. Division in Politics

The Federalist Papers, a collection of essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, primarily aimed to advocate for the ratification of the United States Constitution. While the authors did not directly address the goodness or badness of political parties, they did express concerns about factions and the potential for division in politics. In Federalist No. 10, James Madison famously argued that factions, which can be seen as precursors to political parties, are inevitable in a free society due to the diverse interests and opinions of citizens. However, he warned that factions could lead to instability and tyranny if left unchecked. This sets the stage for a nuanced discussion on unity versus division in politics, as the founders recognized both the challenges and potential consequences of political groupings.

Madison's solution to the problem of factions was not to eliminate them but to control their effects through a large, diverse republic. He believed that in a larger political system, it would be more difficult for any single faction to dominate, thereby fostering a balance that could lead to unity. This idea contrasts sharply with the divisive nature of political parties when they prioritize their interests over the common good. The Federalist Papers, while not explicitly endorsing political parties, implicitly suggest that the structure of government can either mitigate or exacerbate division. A well-designed system, according to the authors, encourages compromise and collaboration, which are essential for maintaining unity in a diverse political landscape.

Despite the founders' efforts to create a system that promotes unity, the rise of political parties in the early years of the United States introduced significant challenges. Parties, by their nature, often emphasize differences and compete for power, which can lead to polarization and division. The Federalist Papers' warnings about factions resonate in today's political climate, where partisan gridlock frequently hinders progress and undermines public trust in government. This division is particularly evident in issues that require bipartisan cooperation, such as healthcare, immigration, and climate change, where ideological differences often take precedence over practical solutions.

To counter this divisiveness, leaders and citizens must prioritize unity by fostering dialogue and understanding across party lines. The Federalist Papers emphasize the importance of a shared commitment to the principles of the Constitution, which can serve as a unifying force. Encouraging civility, promoting fact-based discourse, and focusing on common goals can help bridge the partisan divide. Additionally, electoral reforms, such as ranked-choice voting or open primaries, could incentivize candidates to appeal to a broader electorate rather than catering exclusively to their party's base.

Ultimately, the tension between unity and division in politics reflects the broader human struggle to balance individual interests with the collective good. The Federalist Papers remind us that while factions and political parties are inevitable, their impact on society depends on how we manage them. By embracing the founders' vision of a republic that values compromise and inclusivity, we can work toward a political system that fosters unity rather than division. This requires a conscious effort from all participants in the political process, from elected officials to ordinary citizens, to prioritize collaboration over conflict and the common good over partisan gain.

National and State Political Parties: Structure and Organization Explained

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$17.76

Factions as Inevitable Evil

The Federalist Papers, particularly Federalist No. 10, authored by James Madison, delve into the concept of factions and their role in the political landscape. Madison defines factions as groups of people who share a common interest or passion, which can be adverse to the rights of others or the interests of the community as a whole. While the Papers do not explicitly address modern political parties, they provide a foundational understanding of factions that is highly relevant to the discussion of whether political parties are inherently good or bad. Madison’s argument centers on the idea that factions are an inevitable byproduct of human nature and liberty, making them an "inevitable evil" in a free society.

Madison asserts that the causes of faction are deeply rooted in human nature, arising from the diverse and unequal distribution of property, as well as differing opinions and interests. He argues that as long as people hold varying beliefs and pursue their self-interest, factions will exist. Rather than attempting to eliminate factions, which would require either the destruction of liberty or the creation of homogeneous societies (both impractical and undesirable), Madison suggests that the goal should be to mitigate their harmful effects. This perspective positions factions not as a moral good but as an inescapable reality that must be managed within a constitutional framework.

The inevitability of factions leads Madison to conclude that their negative impacts can only be controlled through structural mechanisms. He advocates for a large, diverse republic where the multitude of factions makes it difficult for any single group to dominate. In such a system, the competition among factions would prevent tyranny of the majority or minority, as no one faction could easily overpower the others. This argument implies that while factions themselves are not inherently good, their proliferation and counterbalancing within a well-designed republic can serve to protect individual rights and maintain stability.

Madison’s analysis in Federalist No. 10 does not endorse factions or political parties as positive forces but rather acknowledges their inevitability and seeks to minimize their potential harm. This contrasts with the modern interpretation of political parties as essential tools for organizing political participation and representation. The Federalist Papers do not celebrate factions but instead treat them as a challenge to be addressed through institutional design. Thus, while political parties might serve functional roles in democracy, the Papers do not assert that they are inherently good; rather, they are a manifestation of the broader, unavoidable phenomenon of factions.

In summary, the Federalist Papers view factions, including those that evolve into political parties, as an inevitable evil stemming from human nature and liberty. Madison’s focus is on managing their effects rather than endorsing their existence as beneficial. This perspective underscores the importance of constitutional safeguards and a diverse republic in controlling the power of factions, positioning them as a necessary but potentially dangerous element of democratic governance. The Papers’ stance on factions as an "inevitable evil" remains a critical insight into the complexities of political organization and the challenges of maintaining a just and stable society.

Can Political Parties Face Legal Action? Exploring the Possibility of Lawsuits

You may want to see also

Checks on Party Influence

The Federalist Papers, a collection of essays advocating for the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, did not explicitly endorse political parties as a positive force in governance. In fact, the Founding Fathers, including Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, who authored the Federalist Papers, were wary of the potential dangers of factions and political parties. Federalist Paper No. 10, written by Madison, is particularly instructive on this point. Madison acknowledged the inevitability of factions in a diverse society but argued that their negative effects could be mitigated through a well-structured republic. This lays the groundwork for understanding the checks on party influence that the Constitution and the Federalist Papers implicitly support.

One of the primary checks on party influence, as envisioned in the Federalist Papers, is the system of separation of powers. By dividing the federal government into three branches—legislative, executive, and judicial—the Constitution ensures that no single faction or party can dominate the political process. Federalist Paper No. 51 emphasizes the importance of this system, where each branch serves as a check on the others, preventing the concentration of power that could be exploited by partisan interests. This structural design forces political parties to negotiate and compromise, reducing the likelihood of one party imposing its will unilaterally.

Another check on party influence is the extended republic envisioned in Federalist Paper No. 10. Madison argued that in a large and diverse nation, it would be more difficult for a single faction or party to gain control because the multiplicity of interests would counteract one another. This diffusion of power across a broad electorate and geographic expanse acts as a natural restraint on the ability of any one party to dominate the political landscape. The size and complexity of the republic, therefore, serve as a built-in mechanism to limit the influence of political parties.

Federalist Paper No. 10 also highlights the role of representative government as a check on party influence. By electing representatives rather than governing directly, the people create a buffer between themselves and the immediate passions of factions. Representatives, Madison argued, are more likely to act with deliberation and a focus on the common good, as opposed to being swayed by the transient interests of a particular party. This system of representation encourages politicians to rise above partisan divides and make decisions that benefit the nation as a whole.

Lastly, the Constitution’s emphasis on federalism provides an additional check on party influence. By dividing power between the federal government and the states, federalism ensures that political parties cannot consolidate control at all levels of governance. State governments act as independent centers of power, capable of resisting overreach by the federal government or dominant political parties. This decentralized structure, as discussed in Federalist Paper No. 46, fosters a balance of power that limits the ability of any single party to exert unchecked influence.

In summary, while the Federalist Papers did not explicitly address political parties as a positive force, they outlined a constitutional framework designed to check their potential excesses. Through separation of powers, the extended republic, representative government, and federalism, the Founding Fathers created a system that inherently limits the influence of political parties. These checks ensure that the government remains responsive to the diverse interests of the people rather than being captured by partisan factions.

Are Political Parties Incorporated? Exploring Legal Structures and Implications

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, the Federalist Papers did not explicitly endorse political parties as good. In fact, the authors, particularly James Madison in Federalist No. 10, warned about the dangers of factions, which they saw as groups driven by self-interest and contrary to the common good.

While the Federalist Papers did not explicitly predict the rise of political parties, they acknowledged the inevitability of factions in a large republic. However, the authors viewed factions as a necessary evil rather than a positive development.

The authors of the Federalist Papers, including Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay, did not support organized political parties. They believed that parties would undermine the stability of the government and lead to divisive conflicts.

The Federalist Papers framed the debate on political parties by emphasizing the risks of factions and advocating for a system that minimized their influence. Despite this, the emergence of political parties, such as the Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, became a reality in the early years of the republic.