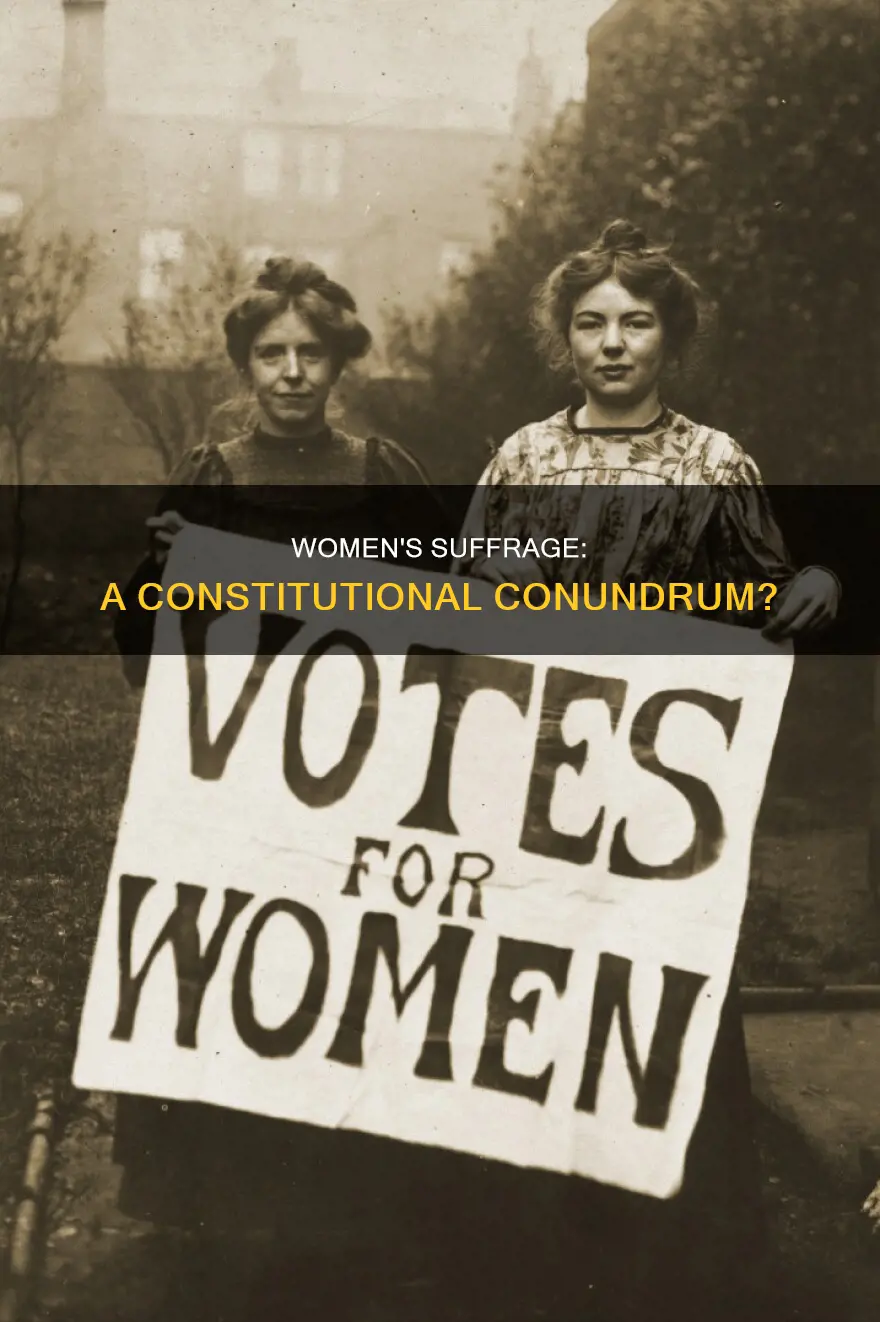

The 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, passed in 1920, granted women the right to vote. However, the road to women's suffrage was long and arduous, spanning over several generations and facing strong opposition. The demand for women's suffrage emerged from the broader movement for women's rights, with the first women's rights convention held in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. While the original U.S. Constitution, adopted in 1789, did not explicitly prohibit women's suffrage, it also did not guarantee it, leaving the boundaries of suffrage undefined.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Year of ratification | 1920 |

| Amendment number | 19th Amendment |

| Number of states needed for ratification | 36 |

| Last state to ratify | Tennessee |

| Number of American women enfranchised | 26 million |

| Year of proposal | 1919 |

| Date of proposal | June 4, 1919 |

| Date of ratification | August 18, 1920 |

| Number of years of activism before ratification | Over 70 |

| First women's rights convention | 1848 |

| First national women's rights convention | 1850 |

| First national suffrage organizations | 1869 |

| First state to adopt woman suffrage | Wyoming |

| Year Wyoming adopted woman suffrage | 1869 |

| Year New York adopted woman suffrage | 1917 |

Explore related products

$9.99 $9.99

What You'll Learn

The 19th Amendment

The road to women's suffrage was long and arduous, spanning over a century and involving the dedicated efforts of generations of activists. The demand for women's suffrage gained momentum in the 1840s, emerging from the broader movement for women's rights. The first women's rights convention, the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, passed a resolution in favour of women's suffrage despite opposition from some organisers who deemed it too extreme. The early activists for women's suffrage included Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lucy Stone, who employed various tactics such as lecturing, writing, marching, lobbying, and civil disobedience to achieve their goal.

In 1869, two rival suffrage organisations were formed: the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), led by Stanton and Anthony, and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), led by Stone. The NWSA focused on lobbying Congress for a national constitutional amendment, while the AWSA pursued a state-by-state approach. Despite their differing strategies, both organisations faced strong opposition to women's enfranchisement.

During the Reconstruction era (1865-1877), women's suffrage leaders advocated for the inclusion of universal suffrage as a civil right in the Reconstruction Amendments. They argued that the Fifteenth Amendment, which prohibited denying voting rights based on "race, colour, or previous condition of servitude", should also imply suffrage for women. However, their efforts were unsuccessful, and the Fourteenth Amendment explicitly discriminated between men and women by only penalising states that deprived adult male citizens of the vote.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, women in Western territories and several states gained the right to vote, but full national suffrage was not achieved until the passage of the 19th Amendment. The amendment enfranchised 26 million American women, but it failed to fully include minority women due to discriminatory laws and practices. The struggle for equal voting rights for minority women continued well beyond the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

Understanding Naturalized Citizens' Constitutional Obligations in the US

You may want to see also

Women's suffrage activism

By the mid-19th century, several generations of women's suffrage supporters lectured, wrote, marched, lobbied, and practiced civil disobedience to achieve what many Americans considered a radical change in the Constitution. Some suffragists used more confrontational tactics, such as picketing, silent vigils, and hunger strikes. The first national suffrage organizations were established in 1869 when two competing organizations were formed: the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), led by Lucy Stone. The NWSA's main effort was lobbying Congress for a women's suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution, while the AWSA generally focused on state-level campaigns.

During the Reconstruction era (1865-1877), women's rights leaders advocated for the inclusion of universal suffrage as a civil right in the Reconstruction Amendments. They unsuccessfully argued that the Fifteenth Amendment, which prohibited denying voting rights based on "race, color, or previous condition of servitude", also implied suffrage for women. The Fifteenth Amendment's focus on race and its exclusion of women led to a schism in the women's suffrage movement, with Stanton and Anthony opposing its passage unless accompanied by another amendment prohibiting the denial of suffrage based on sex. They argued that the amendment would create an "aristocracy of sex" by constitutionally entrenching male superiority.

In the 1870s and 1880s, existing state legislatures in the West and those east of the Mississippi River began to consider suffrage bills, and the movement was revived in the 1890s. In 1878, Senator Aaron A. Sargent, a friend of Susan B. Anthony, introduced a women's suffrage amendment to Congress, which would become the Nineteenth Amendment over forty years later with no changes to its wording. The amendment was finally passed by Congress on June 4, 1919, and ratified on August 18, 1920, granting women the right to vote.

In the second decade of the 20th century, suffragists staged large and dramatic parades to draw attention to their cause. During World War I, they tried to pressure President Woodrow Wilson, who had opposed suffrage, into supporting a federal amendment. By 1916, most major suffrage organizations were united behind the goal of a constitutional amendment, and with New York's adoption of women's suffrage in 1917 and Wilson's shift in position in 1918, the political balance began to shift. Tennessee became the final state to ratify the amendment in 1920, with Alice Paul of the National Woman's Party celebrating the victory.

Christmas Decorations: Free Speech or Sensory Assault?

You may want to see also

Opposition to women's suffrage

The women's suffrage movement faced significant opposition, which was especially strong against the idea of women speaking to mixed-gender audiences. This opposition was not limited to men, as both men and women organized against suffrage. Anti-suffragists argued that most women did not want the vote as they took care of the home and children and did not have time to stay updated on politics. Some even argued that women lacked the mental capacity to offer useful opinions about political issues. Others asserted that women's votes would simply double the electorate, increasing costs without adding any value.

The National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage, formed in 1911, distributed pamphlets with reasons why women did not need to vote. These pamphlets, titled "Household Hints," suggested that voting would mean "competition of women with men instead of cooperation" and that "you do not need a ballot to clean out your sink." While many women found these ideas offensive, some agreed with them. The anti-suffrage movement also used more subtle tactics, such as providing useful household advice alongside anti-suffrage messages. For example, a pamphlet from the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage offered tips like "Sour milk removes ink spots" while discouraging women from "wasting time, energy, and money" on voting.

The opposition to women's suffrage was deeply intertwined with the movement to abolish slavery, with many early suffragists also advocating for the abolition of slavery. However, there was a split in the women's movement, with some suffragists, like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, opposing the 15th Amendment because it excluded women. They warned that black men, who would gain voting power under the amendment, were overwhelmingly opposed to women's suffrage. Frederick Douglass, a strong supporter of women's suffrage, acknowledged this, saying, "The race to which I belong has not generally taken the right ground on this question."

Even after the 19th Amendment was passed in 1920, granting women the right to vote, there were still hurdles to full enfranchisement. The amendment failed to fully include African American, Asian American, Hispanic American, and Native American women. It was not until 1975, with the extension of the Voting Rights Act, that voting materials were required to be provided in languages other than English, making it easier for non-English speakers to exercise their right to vote.

Arrows' Significance: Direction, Focus, and Intent in Design

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The Fifteenth Amendment

> The rights of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, colour, or previous condition of servitude.

The debate over the Fifteenth Amendment and the subsequent split in the women's suffrage movement delayed the campaign for women's voting rights. It would not be until the twentieth century that women's suffrage became a central issue again, with the Nineteenth Amendment finally granting women the right to vote in 1920.

Democratic Republicans: Strict Constitution Interpreters?

You may want to see also

Women's suffrage in the West

The mid-19th century saw several generations of suffragists lecture, write, march, lobby, and practice civil disobedience to achieve this change. Some suffragists employed more confrontational tactics such as picketing, silent vigils, and hunger strikes. The women's suffrage movement suffered a setback during the American Civil War but resumed activities during the Reconstruction era (1865-1877). Two rival suffrage organisations emerged in 1869: the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), led by Lucy Stone. The NWSA lobbied Congress for a women's suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution, while the AWSA focused on state-by-state campaigns.

In the western territories, the issue of women's suffrage gained traction as these territories progressed towards statehood. Through the activism of suffrage organisations and independent political parties, women's suffrage was included in the constitutions of the Wyoming Territory (1869) and Utah Territory (1870). However, women's suffrage in Utah was revoked in 1887 with the passage of the Edmunds-Tucker Act, which also prohibited polygamy. It was only restored in 1896 when Utah achieved statehood. Existing state legislatures in the West and those east of the Mississippi River began considering suffrage bills in the 1870s and 1880s, but it wasn't until the 1890s that the movement was revived, and full women's suffrage continued in Wyoming after it became a state in 1890.

The campaign for women's suffrage continued into the 20th century, with suffragists staging large and dramatic parades to draw attention to their cause. In 1913, over 5,000 suffragists marched in Washington, DC. During World War I, they tried to pressure President Woodrow Wilson, who initially opposed women's suffrage, to support a federal amendment. By 1916, most major suffrage organisations united behind the goal of a constitutional amendment. New York's adoption of women's suffrage in 1917 and Wilson's shift in position in 1918 further bolstered the movement. On June 4, 1919, Congress passed the amendment, and on August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify it, ensuring its passage. The 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution finally granted women the right to vote, enfranchising 26 million American women by the 1920 U.S. presidential election.

However, the fight for equal voting rights continued even after the passage of the 19th Amendment. The amendment failed to fully enfranchise minority women, including African Americans, Asian Americans, Hispanic Americans, and Native Americans. Additionally, states passed laws that continued to disenfranchise women. Activists like Alice Paul pushed for the Equal Rights Amendment to enshrine broad protections against sex-based discrimination in the Constitution, but it failed to gain enough state support by the 1982 deadline. Despite these challenges, the ratification of the 19th Amendment marked a significant step forward in the journey towards women's suffrage in the West, paving the way for further advancements in women's rights.

Electoral College: The Constitutional Conundrum Explored

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, the Constitution did not explicitly prohibit women's suffrage. However, it also did not guarantee women the right to vote. The right to vote for American women was established in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, nationally in 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

The 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution, passed in 1919 and ratified in 1920, granted women the right to vote. It states, "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

The campaign for women's suffrage was long and difficult, with several generations of women supporters lecturing, writing, marching, lobbying, and practising civil disobedience to achieve what many Americans considered a radical change in the Constitution. Some suffragists used more confrontational tactics such as picketing, silent vigils, and hunger strikes.

Some people believed that voting would distract women from their roles as mothers and wives and "ruin happiness in the home". There was also fear regarding the political impact of extending the vote to immigrant women. Many anti-suffragists were upper-class female philanthropists who believed that gaining the right to vote would threaten their power and influence in the family.