The relationship between progressives and political machines in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was complex and often contradictory. While progressives generally sought to reform corrupt and inefficient government systems, their stance on political machines varied. Some progressives, particularly those focused on immediate social and economic reforms, were willing to ally with machines to achieve their goals, as these organizations often had the power to push through legislation. However, many progressives vehemently opposed machines, viewing them as symbols of corruption, patronage, and undemocratic practices that undermined good governance. This tension highlights the pragmatic versus ideological divides within the progressive movement, as well as the challenges of navigating political realities to achieve reform.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Progressive Era Goals | Sought to reform government, reduce corruption, and increase transparency. |

| Political Machines' Nature | Often associated with corruption, patronage, and lack of transparency. |

| Progressive Stance | Generally opposed political machines due to their corrupt practices. |

| Exceptions | Some progressives allied with machines to achieve specific reforms. |

| Reform Efforts | Pushed for civil service reforms, direct primaries, and recall elections. |

| Key Figures | Theodore Roosevelt, Robert La Follette, and others criticized machines. |

| Historical Context | Progressives aimed to dismantle machine politics in the early 20th century. |

| Impact on Machines | Progressive reforms weakened political machines over time. |

| Public Perception | Progressives were seen as anti-machine reformers by the public. |

| Legacy | Progressive reforms led to more democratic and accountable governance. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Progressive Reformers vs. Machine Politics

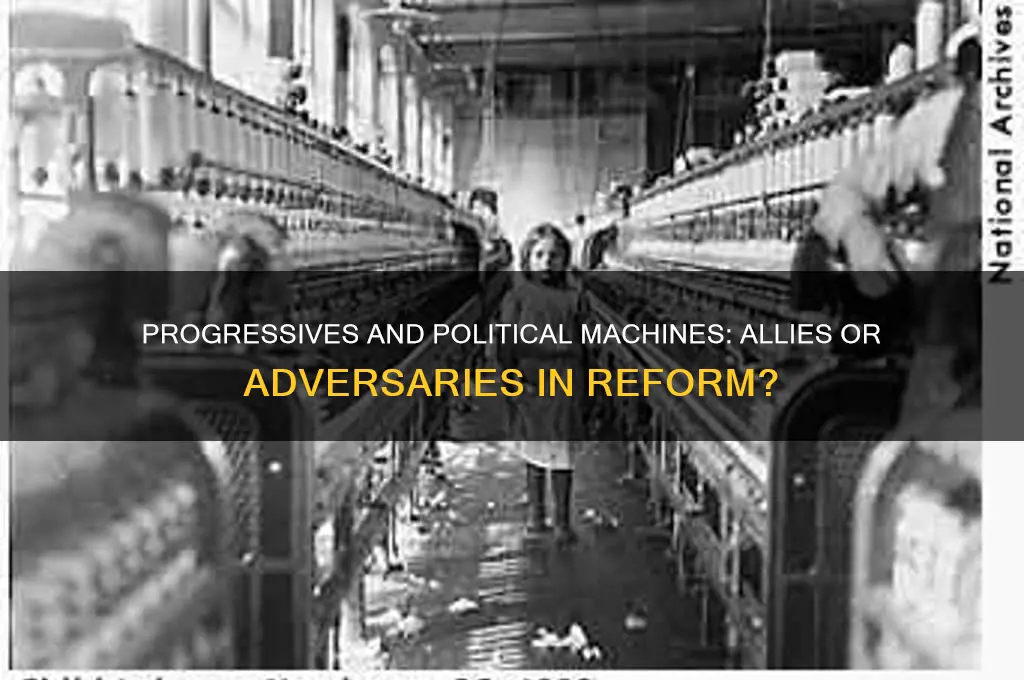

The Progressive Era, spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was marked by a fierce clash between reformers seeking to purify politics and entrenched political machines that thrived on patronage and corruption. At first glance, these two forces seem diametrically opposed. Progressives championed transparency, efficiency, and public welfare, while machines prioritized power consolidation and clientelism. Yet, the relationship was not always adversarial. Some Progressives, particularly in their early stages, inadvertently benefited from machine politics, using its structures to advance reforms. For instance, in cities like Cleveland, Progressive mayors like Tom L. Johnson worked within machine frameworks to implement public transit reforms and lower utility rates, demonstrating a pragmatic alliance.

However, such collaborations were the exception rather than the rule. Progressives fundamentally rejected the core tenets of machine politics. They viewed machines as corrupt, undemocratic, and antithetical to good governance. Machines, controlled by bosses like Chicago’s William Hale Thompson, relied on voter intimidation, fraud, and kickbacks to maintain power. Progressives countered with structural reforms like the secret ballot, direct primaries, and civil service exams to dismantle machine control. These measures aimed to shift power from party bosses to informed citizens, a direct assault on machine politics.

One of the most effective Progressive strategies was the implementation of nonpartisan elections and city manager systems. By removing party labels from local elections, Progressives sought to weaken machine influence and focus on administrative competence. For example, Galveston, Texas, adopted a city commission government in 1901, sidelining partisan politics and prioritizing efficiency. While these reforms often succeeded in curbing machine power, they also risked depoliticizing local governance, a critique that persists today.

Despite their successes, Progressive reformers faced limitations. Machines were deeply embedded in urban communities, providing jobs, services, and social cohesion to immigrant populations. Progressives, often from middle-class backgrounds, struggled to replace these functions. In cities like New York, Tammany Hall’s ability to deliver tangible benefits to marginalized groups made it resilient to reform efforts. This dynamic highlights a key tension: while Progressives sought to purify politics, machines thrived by addressing immediate community needs, albeit through questionable means.

In conclusion, the Progressive-machine conflict was not merely ideological but also practical. Progressives sought to replace patronage with professionalism, corruption with transparency, and partisanship with nonpartisanship. While they achieved significant victories, their reforms were not without trade-offs. The legacy of this struggle continues to shape American politics, reminding us that the fight for clean governance often requires navigating complex social and institutional realities.

Analyzing Bias: Decoding the Political Slant of Your News Source

You may want to see also

Corruption and Patronage Concerns

The Progressive Era, often celebrated for its reforms and idealism, was paradoxically marked by a complex relationship with political machines. While progressives championed transparency, efficiency, and public welfare, their stance on these machines was not uniformly adversarial. Many progressives recognized that political machines, despite their flaws, often delivered tangible benefits to marginalized communities, such as jobs, housing, and social services. However, this pragmatic acceptance did not erase their deep-seated concerns about corruption and patronage, which they viewed as antithetical to good governance.

Consider the Tammany Hall machine in New York City, a quintessential example of the patronage system. Progressives like Theodore Roosevelt acknowledged that Tammany’s ability to mobilize resources for immigrants and the poor was undeniable. Yet, they were equally critical of its corrupt practices, such as vote buying, graft, and the appointment of unqualified loyalists to public offices. This duality highlights a key Progressive dilemma: how to dismantle systemic corruption without dismantling the support systems that vulnerable populations relied upon.

To address these concerns, progressives employed a multi-pronged strategy. First, they advocated for civil service reforms, such as the Pendleton Act of 1883, which introduced merit-based hiring to reduce patronage appointments. Second, they pushed for direct primaries and the secret ballot to minimize voter coercion and fraud. Third, they championed investigative journalism and public exposure of corrupt practices, leveraging the power of the press to hold machine bosses accountable. These measures were not just theoretical; they were practical steps to curb corruption while preserving the positive functions of political machines.

However, the Progressive approach was not without its limitations. By focusing on structural reforms, they often overlooked the root causes of corruption, such as economic inequality and the lack of alternative support systems for marginalized groups. For instance, while civil service reforms reduced patronage, they also limited access to jobs for immigrants and African Americans who had previously relied on machine networks. This unintended consequence underscores the delicate balance progressives sought to achieve: rooting out corruption without exacerbating social inequities.

In conclusion, the Progressive stance on political machines was shaped by a nuanced understanding of their dual nature—both as vehicles for corruption and as lifelines for the disenfranchised. Their efforts to address corruption and patronage concerns were marked by innovation and pragmatism, but also by challenges that revealed the complexities of reform. For modern policymakers grappling with similar issues, the Progressive Era offers a cautionary tale: reform must be both principled and practical, addressing systemic flaws without disregarding the human costs.

Changing Sides: A Guide to Switching Political Affiliations Wisely

You may want to see also

Efficiency vs. Democracy Debate

The Progressive Era's ambivalence toward political machines reveals a tension between their desire for efficient governance and their commitment to democratic ideals. Progressives, appalled by the corruption and inefficiency of machine politics, sought to dismantle these systems through civil service reform, direct primaries, and recall elections. Yet, some machines delivered tangible benefits to immigrant communities, raising the question: could efficiency sometimes trump democratic purity?

Consider the case of Tammany Hall in New York City. While notorious for graft and patronage, Tammany provided crucial social services to marginalized groups, filling a void left by the state. This pragmatic efficiency, though undemocratic in its methods, highlights the complexities of the debate.

Progressives, in their zeal for reform, often prioritized efficiency over inclusivity. Their push for expert-driven administration and bureaucratic rationalization risked marginalizing the very communities machines, however flawed, had served. This raises a crucial point: efficiency, when divorced from democratic participation, can lead to technocratic rule, where decisions are made by a select few, not the people.

Imagine a city council dominated by technocrats, making decisions based solely on data and cost-benefit analyses, disregarding the voices of those most affected. This scenario, while efficient, would be a far cry from the democratic ideal of government by and for the people.

The efficiency vs. democracy debate within the Progressive Era isn't merely historical; it resonates today. We see it in discussions about the role of data-driven algorithms in decision-making, the balance between expert opinion and public input, and the tension between streamlining bureaucracy and ensuring transparency.

To navigate this tension, we must remember that efficiency should serve democracy, not supplant it. This means creating systems that are both effective and accountable, where expertise is valued but not allowed to overshadow the voices of citizens.

Ultimately, the Progressive Era's struggle with political machines offers a cautionary tale. While efficiency is essential for effective governance, it must be balanced with a commitment to democratic principles. This requires constant vigilance, ensuring that the pursuit of efficiency doesn't come at the expense of the very ideals Progressives fought to uphold: transparency, accountability, and the active participation of all citizens in the democratic process.

Setting Boundaries: How to Politely Decline Overtime Requests at Work

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Urban Reform Efforts

The Progressive Era, spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was marked by a surge in urban reform efforts aimed at dismantling the corrupt political machines that dominated city governments. These machines, often tied to major parties like Tammany Hall in New York, thrived on patronage, graft, and voter manipulation. Progressives, however, sought to replace this system with transparent, efficient governance. Their reforms included civil service reforms to merit-based hiring, direct primaries to bypass machine-controlled nominations, and nonpartisan elections to reduce party influence. These measures were designed to empower citizens and weaken the stranglehold of political bosses.

One of the most effective tools in the Progressive arsenal was the implementation of the commission form of government, exemplified by Galveston, Texas, in 1901. This system replaced the mayor-council structure with a small group of commissioners, each overseeing specific departments like public works or finance. By consolidating power and reducing opportunities for corruption, this model aimed to streamline governance. However, its success varied; while it improved efficiency in some cities, it also risked concentrating power in fewer hands, potentially recreating machine-like dynamics.

Another cornerstone of urban reform was the push for public health and safety improvements. Progressives advocated for sanitation reforms, clean water initiatives, and housing regulations to combat the squalid conditions of industrial cities. For instance, the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 and the Meat Inspection Act were direct responses to exposés like Upton Sinclair’s *The Jungle*. These reforms not only improved living standards but also demonstrated how government intervention could address systemic issues, challenging the laissez-faire approach favored by machine politicians.

Despite their successes, Progressive urban reforms were not without limitations. While they targeted political corruption, they often overlooked the social and economic inequalities that fueled machine politics. For example, machines thrived by providing services to immigrant communities neglected by mainstream institutions. Progressives’ focus on efficiency and moral governance sometimes alienated these groups, who relied on machines for survival. This oversight highlights the complexity of reform: dismantling corrupt systems required not just structural changes but also addressing the root causes of their appeal.

In conclusion, Progressive urban reform efforts were a bold attempt to redefine city governance in the face of entrenched political machines. Through structural changes, public health initiatives, and a commitment to transparency, they achieved significant victories. Yet, their inability to fully address the socio-economic underpinnings of machine politics serves as a cautionary tale. True reform, as Progressives demonstrated, must balance institutional change with an understanding of the human needs that sustain flawed systems.

Building Unity: Strategies for Sustaining Political Consensus Effectively

You may want to see also

Progressive-Machine Alliances in Cities

In the early 20th century, Progressive reformers often found themselves in a pragmatic alliance with urban political machines, despite their ideological differences. Progressives, driven by a desire to improve governance and reduce corruption, initially saw machines as obstacles due to their patronage systems and lack of transparency. However, in cities like Chicago and New York, Progressives realized that machines controlled the levers of power and could deliver immediate reforms if aligned with their goals. This uneasy partnership allowed Progressives to implement policies such as public health initiatives, labor protections, and infrastructure improvements, leveraging the machines’ organizational strength and voter mobilization capabilities.

Consider the case of Robert La Follette in Wisconsin, a Progressive leader who initially fought machines but later worked within the system to achieve reform. La Follette’s strategy involved co-opting machine tactics, such as grassroots organizing and targeted legislation, to build a coalition that could challenge entrenched interests. Similarly, in Cleveland, Progressive mayor Tom L. Johnson collaborated with machine operatives to pass tax reforms and public transit improvements. These examples illustrate how Progressives adapted their strategies, recognizing that machines, for all their flaws, had the infrastructure to enact change at scale.

However, these alliances were not without risks. Progressives often had to compromise their principles, such as tolerating patronage appointments or turning a blind eye to minor corruption, to secure machine support. This moral ambiguity created internal tensions within the Progressive movement, with purists arguing that such compromises undermined their long-term goals. For instance, in St. Louis, Progressive-machine collaborations led to significant public works projects but also entrenched machine power, making future reforms more difficult. Balancing immediate gains against the risk of co-optation became a defining challenge for Progressives in these alliances.

To navigate these complexities, Progressives developed strategies to maintain their independence while leveraging machine resources. One tactic was to focus on issue-specific collaborations, such as public health campaigns or education reform, where machines had a vested interest in success. Another was to build parallel grassroots networks that could counterbalance machine influence over time. For example, Jane Addams’ Hull House in Chicago served as both a reform hub and a counterweight to machine politics, demonstrating how Progressives could work within the system without becoming fully absorbed by it.

In conclusion, Progressive-machine alliances in cities were a pragmatic response to the realities of urban politics. While these partnerships enabled significant reforms, they required careful navigation of ethical and strategic trade-offs. By studying these historical examples, modern reformers can glean insights into how to work within flawed systems to achieve meaningful change, all while safeguarding their core principles. The key lies in understanding the machines’ strengths and limitations, and crafting alliances that maximize public benefit without sacrificing long-term integrity.

How Political Decisions Reshape Daily Lives and Societal Norms

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Progressives generally opposed political machines, viewing them as corrupt and undemocratic systems that undermined good governance.

Progressives criticized political machines for their reliance on patronage, bribery, and voter manipulation, which they believed stifled reform and public accountability.

In some cases, progressives reluctantly allied with political machines to achieve specific reforms, but these were exceptions rather than the rule.

Progressives advocated for civil service reforms, direct primaries, and other measures to reduce machine influence and promote transparent, merit-based governance.

While progressives made significant strides in reducing machine power, they did not entirely eliminate political machines, which continued to operate in some regions.