George Washington, the Founding Father of the United States, had a complicated relationship with slavery. While he owned slaves himself, his views on the institution evolved over time, and he ultimately freed his slaves upon his death. During his lifetime, Washington avoided making public statements or taking decisive action against slavery, likely due to financial concerns, the potential for political backlash, and the fragile state of the nation. However, his private letters and will provide insight into his changing attitudes and his desire to see the abolition of slavery. The Constitution, which Washington presided over during its drafting, allowed for the preservation of slavery and avoided using the word slave, leaving the decision to keep, change, or eliminate the institution to individual states.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Did George Washington own slaves? | Yes, he owned slaves from the age of 11 until his death. |

| Did George Washington free his slaves? | Yes, in his will, Washington freed all the slaves he owned. |

| How many slaves did George Washington own? | In 1799, Washington owned 123 slaves. |

| Did George Washington profit from slavery? | No, in the last decades of his life, the profits from his farmland did not cover the cost of feeding and clothing his slaves. |

| Did George Washington publicly support the abolition of slavery? | No, he avoided the issue publicly, believing that debates over slavery could tear apart the nation. |

| Did George Washington support slavery in the Constitution? | As president of the Constitutional Convention, Washington did not intervene to abolish slavery. The Constitution allowed but did not require the preservation of slavery. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

George Washington's will freed all his slaves

George Washington, the preeminent Founding Father of the United States, was an enslaver for 56 years. He inherited his first slaves at the age of 11 when his father died in 1743. Washington's attitude towards slavery was complex and appeared to change over time. In a private letter to John Mercer in 1786, he wrote of his dislike for the institution of slavery, noting that it violated the ideals of freedom and equality. He also endorsed a document known as the Fairfax Resolves in 1774, which condemned the slave trade as "unnatural".

Despite these sentiments, Washington did not publicly advocate for emancipation during his lifetime. He declined an invitation from leading French abolitionist Jacques Brissot to form and become president of an abolitionist society in Virginia, stating that while he supported such a society, the time was not right to confront the issue. Washington's will, drafted in 1799, provides further evidence of his complicated relationship with slavery. He expressed a desire to free all his slaves at Mount Vernon, but also stipulated that they should remain with his wife, Martha Washington, for the rest of her life. This decision was likely influenced by the fact that some of the slaves at Mount Vernon were inherited by Martha from her first husband and were therefore not technically his to free.

After Washington's death, Martha freed only one slave, William Lee, a Revolutionary War celebrity who had served as Washington's body servant. The rest of Washington's enslaved workers were freed by Martha about a year after his death, in January 1801. This decision was influenced by the increasing restiveness of the enslaved people, as well as the financial burden of maintaining them. It is worth noting that the 153 enslaved people inherited by Martha from her first husband were not freed and were instead divided among her grandchildren after her death in 1802.

In conclusion, while George Washington's will did ultimately lead to the freedom of his slaves, the process was more complicated than a simple act of emancipation. The delay in freeing the enslaved people at Mount Vernon and the continued enslavement of those inherited by Martha highlight the complex dynamics surrounding slavery during that time.

Where Does the Vice President Live?

You may want to see also

Washington's evolving views on slavery

George Washington, the Founding Father of the United States, had evolving views on slavery. He was a slave owner himself, and his early views on slavery reflected the prevailing Virginia planter views of the time, demonstrating few moral qualms, if any. In his early life, Washington accepted slavery without apparent concern and referred to slaves as "a species of property".

However, his views gradually changed, and he became increasingly uneasy with the institution of slavery. In 1774, he endorsed a document known as the Fairfax Resolves, which condemned the slave trade as "unnatural" and recommended that no more enslaved people be imported into the British colonies. This marked the beginning of a slow evolution in his attitude towards slavery. Washington's early objections to slavery were primarily economic, as he found that slavery was not an efficient labor system for his plantation. However, he later added moral objections, stating that slavery violated the ideals of freedom and equality.

In a private letter to fellow Virginian John Mercer in 1786, Washington avowed his dislike of slavery and his desire to see it abolished by a gradual legislative process. He wrote, "I never mean...to possess another slave by purchase; it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted by which slavery in this Country may be abolished by slow, sure, & imperceptible degrees." Despite his private objections to slavery, Washington prioritized national unity over its abolition during his presidency. He declined an invitation from leading French abolitionist Jacques Brissot to form and become president of an abolitionist society in Virginia, stating that while he supported such a society, the time was not yet right to confront the issue.

At the time of his death in 1799, Washington owned 123 slaves. In his will, he freed one of his slaves immediately and required that the remaining 123 be freed upon the death of his wife, Martha Washington. This decision marked the culmination of two decades of introspection and inner conflict for Washington, as his views on slavery changed gradually but dramatically. Martha Washington signed a deed of manumission for her husband's enslaved people, and they were finally emancipated on January 1, 1801.

The Four Powers: How the House Wields Control and Influence

You may want to see also

Washington's avoidance of public statements on slavery

George Washington, the Founding Father of the United States, had a complicated relationship with slavery. While he privately expressed his dislike of the institution and his desire to see it abolished, he avoided making public statements on the issue during his lifetime.

Washington grew up in Virginia, where slavery was a longstanding institution dating back over a century. He became a slave owner at the age of 11 when he inherited his first ten slaves from his father in 1743. Over the years, Washington acquired more slaves through inheritance, marriage, and purchase, and by 1799, he owned 123 enslaved people at his Mount Vernon estate.

Despite his personal opposition to slavery, Washington avoided making public statements or taking decisive action to end the practice during his lifetime. He believed that bitter debates over slavery could tear apart the fragile nation and that his political influence as president would be diminished if he took a strong public stance. Washington also had concerns about his finances, as he found that slavery was economically inefficient, and he worried about the potential for separating enslaved families.

In private communications, Washington expressed his desire to see slavery abolished. In a 1786 letter to John Mercer, he wrote, "I never mean...to possess another slave by purchase; it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted by which slavery in this Country may be abolished." Washington also endorsed the Fairfax Resolves in 1774, which condemned the slave trade as "unnatural" and recommended ending the import of enslaved people into the British colonies.

While Washington avoided public statements on slavery, he did take some action on the issue. He approved a plan in 1779 to grant enslaved men their freedom in exchange for service in the Continental Army. Additionally, he freed one slave in his will and required the remaining 123 slaves to serve his wife and be freed no later than her death. Ultimately, they became free one year after his death in 1799, making him the only US president to have freed all his slaves upon his passing.

Constitutional Republics: True Democracy or Not?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The economic inefficiency of slavery

The economic efficiency of slavery has been a topic of debate among historians and economists. While some argue that slavery was profitable and efficient, others contend that it was inefficient and immoral. Let's delve into the arguments and explore the economic inefficiency of slavery.

Historical Context:

The issue of slavery was explosive during the Constitutional Convention in 1787, which George Washington presided over. At that time, slavery was legal in all 13 colonies, with one-fifth of the population living in bondage. Washington himself was a slave owner, inheriting his first slaves at the age of 11 upon his father's death. However, his attitude towards slavery evolved, and he privately expressed his dislike of the institution, recognizing its violation of freedom and equality.

Economic Inefficiency Arguments:

Many classical economists, starting with Adam Smith, argued that slave labor was inefficient and unprofitable. Smith, in "The Wealth of Nations" (1776), wrote, "great improvements [...] are least of all to be expected when they [proprietors] employ slaves for their workmen." He attributed the persistence of slavery not to its economic efficiency but to "the pride of man," suggesting that employers preferred the service of slaves due to a desire for domination.

Other economists, including Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot, Jean-Baptiste Say, Heinrich von Storch, Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, and John Cairnes, concurred with Smith's condemnation of slavery as inefficient. They integrated their economic analysis with a moral condemnation of the practice.

- Output Inefficiency: Slaveholders may have saved on wages compared to employing free workers, but they incurred costs for room, board, food, clothing, and medical treatment for their slaves. These costs could outweigh any savings, especially as the slave population grew due to birth rates, increasing expenses for food, shelter, and security.

- Enforcement Inefficiency: Slaveholders had to incur significant costs to maintain secrecy and avoid detection, particularly in modern times, where many countries have made slavery illegal. They may have to pay bribes to authorities or face public condemnation and intervention from humanitarian groups and government bodies.

- Classical Inefficiency: The notion that slavery operated like a tax on work, with transfers from poor slaves to rich slaveholders. Even if slaveholder gains equaled slave losses, welfare losses could still exceed gains, indicating inefficiency.

- Scale and Revolt: As the slave population increased, it became more challenging and costly to prevent revolts or escapes, further diminishing efficiency over time.

- Immoral and Immune to Market Forces: Slavery is based on coercion and exploitation, making it difficult to sustain in a free market. The attitude and motivation of slaves, often performing low-skill labor, may differ significantly from that of free workers.

In conclusion, while slavery may have provided short-term economic benefits to some, such as stimulating industrialization and providing raw materials, the totality of factors and costs associated with slavery reveals its economic inefficiency. The practice was immoral and exploitative, and its persistence was due to non-economic factors, such as the desire for domination and the entrenched nature of the institution.

DND Constitution Classes: Exploring the Options

You may want to see also

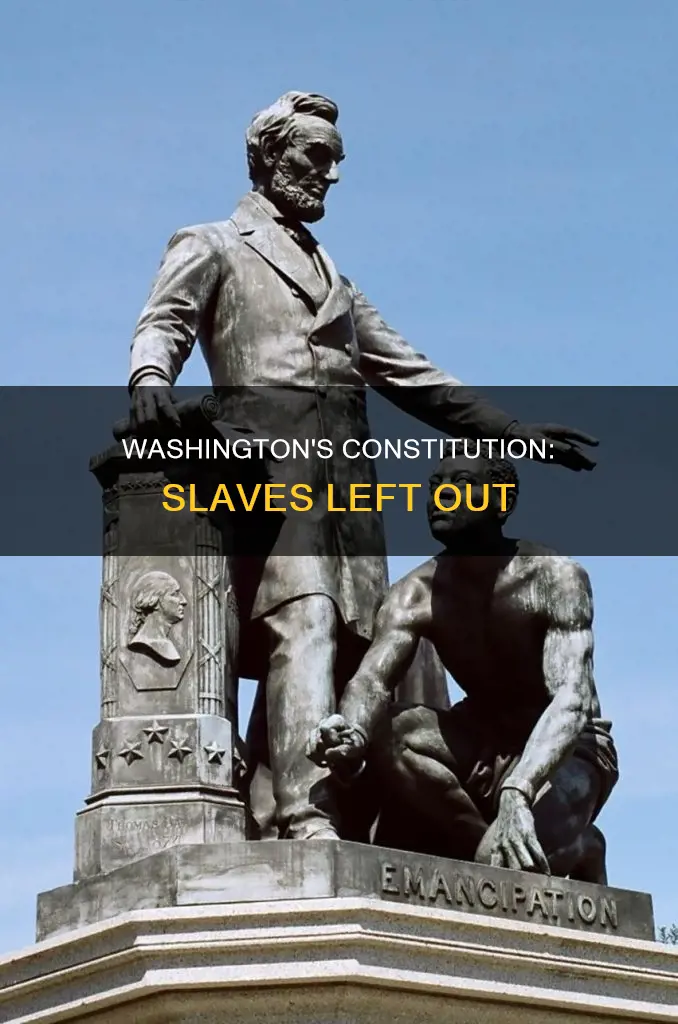

The Constitution's concessions to protect slavery

The Constitution contained several concessions to protect slavery, despite the moral qualms of many of its framers. The document deliberately avoided using the word "slave", instead including clauses that protected the institution of slavery. For example, the Fugitive Slave Clause required the return of runaway slaves to their owners, and another clause promised that Congress would not prohibit the transatlantic slave trade for twenty years. The Constitution also empowered Congress to authorise the suppression of insurrections, such as slave rebellions.

The Three-Fifths Clause is another example of a concession to protect slavery. This clause counted three-fifths of a state's slave population when apportioning representation, giving the South extra representation in the House of Representatives and extra votes in the Electoral College. This clause has been interpreted as giving greater power to the Southern states, although Frederick Douglass believed it encouraged freedom because it gave "an increase of 'two-fifths' of political power to free over slave states".

The support of the Southern states for the new constitution was secured by granting them these concessions that protected slavery. This was despite the fact that many of the framers of the Constitution, including Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton, were members of anti-slavery societies. George Washington, who presided over the Constitutional Convention, also expressed his dislike of the institution of slavery in a private letter, stating that he wished to see "some plan adopted by which slavery in this Country may be abolished by slow, sure, & imperceptible degrees".

While the Constitution made concessions to protect slavery, it also created a central government powerful enough to eventually abolish the institution. By the time of Washington's death in 1799, there were eight free states and nine slave states, and this split was considered entirely constitutional. Washington himself freed all of his slaves upon his death, and his will stipulated that elderly or sick enslaved people were to be supported by his estate in perpetuity.

The US Cabinet: A Comprehensive Overview of Positions

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

No, George Washington did not leave out slaves in the Constitution. In fact, the Constitution allowed for the preservation of slavery, and it avoided using the word "slave" to prevent authorising the treatment of humans as property.

George Washington's stance on slavery changed over time. He owned slaves from the age of 11 until his death, but he also expressed his dislike of the institution of slavery and his desire to see it abolished. In his will, he freed all the slaves he owned.

No, George Washington did not address slavery publicly during his lifetime. He believed that debates over slavery could tear apart the nation and delayed taking major action. However, his will, which freed all the slaves he owned, became public after his death in 1799.