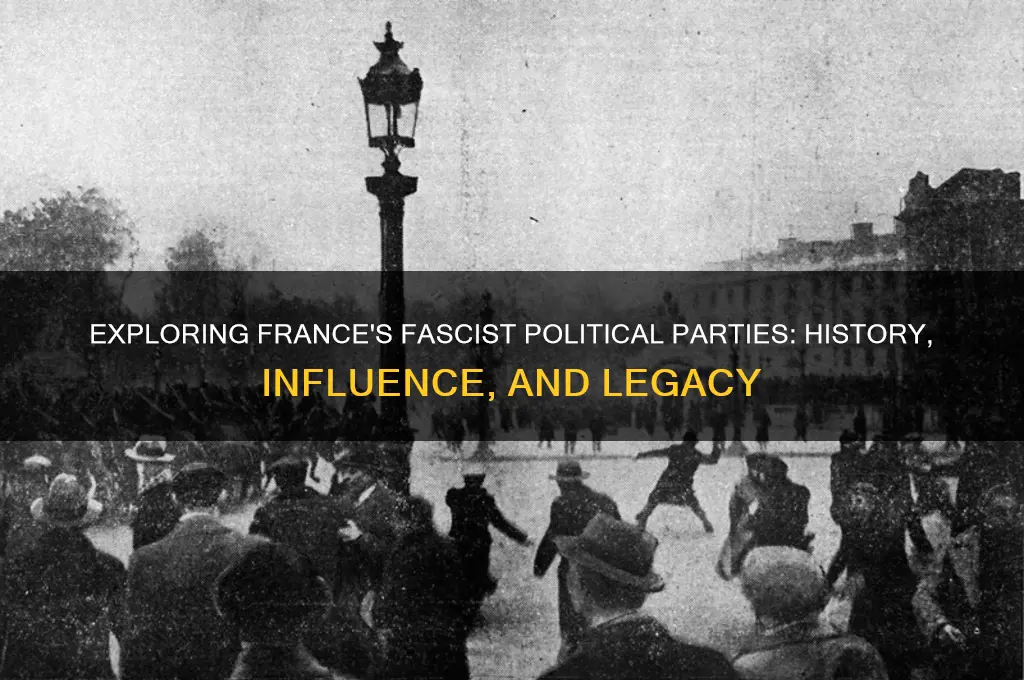

France, like many European countries in the interwar period, experienced the rise of various political movements, including those with fascist tendencies. While France did not see the establishment of a single dominant fascist party akin to Italy's National Fascist Party or Germany's Nazi Party, it did witness the emergence of several far-right and fascist-leaning political groups. These parties, such as the *Action Française*, *Croix-de-Feu*, and *Parti Populaire Français (PPF)*, advocated for nationalism, authoritarianism, and anti-parliamentarianism, often drawing inspiration from Mussolini and Hitler. Although these movements gained some traction, particularly during the 1930s, they remained fragmented and failed to achieve widespread political dominance, partly due to France's strong republican traditions and the resistance from left-wing and centrist forces. The outbreak of World War II and the Vichy regime further complicated the legacy of fascism in France, as collaboration with Nazi Germany overshadowed the earlier fascist movements.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Existence of Fascist Parties | Yes, France had several political parties with fascist ideologies. |

| Prominent Fascist Parties | - Action Française (founded in 1899) |

| - Croix-de-Feu (founded in 1927, later became Parti Social Français) | |

| - Parti Populaire Français (founded in 1936) | |

| Ideological Features | - Ultranationalism |

| - Anti-parliamentarianism | |

| - Corporatism | |

| - Authoritarianism | |

| Historical Context | Most active during the 1920s–1940s, particularly in the interwar period. |

| Peak Influence | Gained significant support during the 1930s economic and political crises. |

| Relationship with Vichy Regime | Some fascist parties collaborated with the Vichy government (1940–1944). |

| Post-WWII Status | Fascist parties were largely disbanded or marginalized after 1945. |

| Modern Presence | No major fascist parties exist today, but far-right groups persist. |

| Legal Status | Fascist ideologies are not banned but face strong societal opposition. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Action Française: Royalist, nationalist movement with fascist tendencies, influential in the 1930s

- Croix-de-Feu: Veterans' league turned fascist-leaning political party under François de La Rocque

- Parti Populaire Français (PPF): Openly fascist party led by Jacques Doriot, allied with Nazis

- Jeunesses Patriotes: Far-right league with fascist elements, active in the 1920s-1930s

- Fascist Influence in Vichy: Collaborationist regime during WWII with fascist characteristics under Pétain

Action Française: Royalist, nationalist movement with fascist tendencies, influential in the 1930s

Action Française was a prominent royalist and nationalist movement in France that exhibited fascist tendencies, particularly during the 1930s. Founded in 1899 by Charles Maurras, a staunch monarchist and intellectual, the movement sought to restore the French monarchy and promote a conservative, authoritarian vision of the nation. While not a fascist party in the strictest sense, Action Française shared many ideological similarities with fascism, including its emphasis on nationalism, anti-parliamentarianism, and the rejection of liberal democracy. Its influence grew significantly in the interwar period, as it capitalized on widespread disillusionment with the Third Republic and the social unrest following World War I.

The movement's ideology was rooted in Maurras's philosophy of "integral nationalism," which posited that France's greatness could only be restored through the revival of its traditional institutions, particularly the monarchy. Action Française also embraced anti-Semitism, blaming Jews and Freemasons for the nation's decline, a stance that aligned it with fascist movements elsewhere in Europe. Its paramilitary wing, the *Camelots du Roi*, engaged in street violence and intimidation tactics, further mirroring the aggressive methods of fascist organizations. Despite its royalist core, the movement's authoritarianism, ultranationalism, and disdain for parliamentary democracy led many historians to categorize it as having fascist tendencies.

In the 1930s, Action Française gained considerable influence, particularly among the Catholic bourgeoisie, military officers, and parts of the intellectual elite. Its newspaper, *L'Action Française*, became a powerful platform for spreading its ideas, and the movement's youth organizations attracted thousands of members. However, its impact was limited by internal divisions and its failure to fully embrace modernity or appeal to the working class, unlike fascist parties in Italy and Germany. Additionally, the movement's staunch Catholicism and monarchist goals set it apart from the secular, revolutionary nature of fascism.

Action Française's role in French politics was further complicated by its ambiguous relationship with fascism. While Maurras admired Mussolini's authoritarian regime, he rejected Hitler's racial theories due to their anti-Catholic and anti-monarchist elements. This ideological inconsistency prevented the movement from fully aligning with fascism, though its methods and rhetoric often overlapped. The movement's influence began to wane after the 1930s, particularly following the rise of more overtly fascist groups like the *Parti Populaire Français* (PPF) led by Jacques Doriot.

Despite its decline, Action Française left a lasting legacy in French political thought, shaping the intellectual foundations of the far right. Its blend of nationalism, traditionalism, and authoritarianism continued to resonate in later movements, even as France's fascist parties remained relatively marginal compared to those in other European countries. In examining whether France had fascist political parties, Action Française stands out as a unique case—a movement with fascist tendencies but rooted in a distinct, royalist ideology. Its influence in the 1930s underscores the complexity of fascism's manifestation in France, where it often intertwined with other conservative and nationalist traditions.

Switching Sides: Can Politicians Change Parties While in Office?

You may want to see also

Croix-de-Feu: Veterans' league turned fascist-leaning political party under François de La Rocque

The Croix-de-Feu, initially founded in 1927 as a veterans' association, underwent a significant transformation under the leadership of Colonel François de La Rocque, evolving into a fascist-leaning political party in interwar France. Originally established to provide mutual aid and camaraderie among World War I veterans, the organization quickly expanded its scope in response to the social and economic crises of the 1930s. La Rocque, a charismatic and ambitious leader, took control in 1930 and began to reshape the Croix-de-Feu into a paramilitary-style movement with a nationalist and authoritarian agenda. This shift reflected the growing appeal of fascist ideologies across Europe, as traditional political structures struggled to address widespread unemployment, inflation, and political instability.

Under La Rocque's guidance, the Croix-de-Feu adopted a highly disciplined and hierarchical structure, mirroring fascist organizations in Italy and Germany. Members wore uniforms, participated in marches, and were organized into local units, fostering a sense of unity and purpose. The movement's rhetoric emphasized national revival, order, and the rejection of parliamentary democracy, which La Rocque and his followers viewed as corrupt and ineffective. While the Croix-de-Feu stopped short of fully embracing racial theories or extreme violence, its anti-communist stance, corporatist economic ideas, and calls for a strong, centralized state aligned it closely with fascist principles. This ideological shift attracted a broad base of supporters, including veterans, middle-class citizens, and disillusioned conservatives.

The Croix-de-Feu's rise to prominence was marked by its involvement in the February 6, 1934, riots in Paris, a pivotal event in French political history. The riots, sparked by allegations of government corruption, saw the Croix-de-Feu and other right-wing groups clash with police, leading to several deaths. Although the movement did not directly incite the violence, its presence and organization during the unrest underscored its potential as a political force. In the aftermath, La Rocque sought to capitalize on the momentum by transforming the Croix-de-Feu into a formal political party, the Parti Social Français (PSF), in 1936. This transition marked a strategic shift from street activism to electoral politics, as La Rocque aimed to influence the French state from within.

Despite its fascist-leaning tendencies, the Croix-de-Feu and its successor, the PSF, maintained a degree of ambiguity in their ideological positioning. La Rocque often distanced himself from the label of fascism, emphasizing instead the movement's commitment to social justice, national unity, and Christian values. This nuanced approach allowed the PSF to appeal to a wider audience, becoming one of the largest right-wing parties in France by the late 1930s. However, the movement's authoritarian inclinations and its opposition to the Popular Front government of Léon Blum raised concerns among democrats and left-wing groups. The PSF's influence waned after the outbreak of World War II, as La Rocque's attempts to navigate the complexities of the Vichy regime and the German occupation ultimately led to the party's dissolution in 1940.

In retrospect, the Croix-de-Feu under François de La Rocque exemplifies the complex interplay between nationalism, authoritarianism, and fascism in interwar France. While it never fully embraced the extremes of fascism, its paramilitary structure, anti-democratic rhetoric, and corporatist ideals placed it firmly within the fascist spectrum. The movement's evolution from a veterans' league to a political party highlights the broader appeal of authoritarian solutions during a time of crisis, offering valuable insights into the diversity and adaptability of fascist movements in Europe. The Croix-de-Feu's legacy remains a testament to the challenges of defining fascism and the enduring tensions between democracy and authoritarianism in French political history.

Are We Ready for a Second Political Party?

You may want to see also

Parti Populaire Français (PPF): Openly fascist party led by Jacques Doriot, allied with Nazis

The Parti Populaire Français (PPF), founded in 1936 by Jacques Doriot, was one of the most prominent and openly fascist political parties in France. Doriot, a former Communist mayor of Saint-Denis, underwent a dramatic ideological shift in the mid-1930s, embracing fascism and becoming a staunch admirer of Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler. The PPF was explicitly modeled after fascist movements in Italy and Germany, adopting similar rhetoric, symbols, and organizational structures. Its platform emphasized nationalism, anti-communism, and the rejection of parliamentary democracy, advocating instead for a corporatist state under strong leadership.

Under Doriot's leadership, the PPF quickly aligned itself with Nazi Germany, becoming a key collaborator during the German occupation of France in World War II. The party's ideology was deeply anti-Semitic, and it actively supported the Vichy regime's policies of discrimination and persecution against Jews. The PPF also played a role in recruiting French volunteers for the Waffen-SS and other Nazi military units, further cementing its alliance with the Third Reich. Doriot himself became a fervent advocate for Nazi policies, even traveling to Germany to meet with high-ranking officials and solidify the party's ties to the Nazi regime.

The PPF's fascist character was evident in its paramilitary wing, the Service d'Ordre, which was responsible for street violence and intimidation tactics against political opponents, particularly communists and socialists. The party's propaganda machine, including its newspaper *Le Cri du Peuple*, disseminated fascist and pro-Nazi ideas, seeking to mobilize public support for its authoritarian vision. Despite its efforts, the PPF never achieved mass popularity, remaining a relatively small but highly visible and radical force in French politics.

During the German occupation, the PPF's collaborationist activities intensified, as it sought to position itself as a potential governing party in a Nazi-dominated Europe. However, its extreme positions and Doriot's personal ambitions alienated many potential allies, even within the Vichy regime. After Doriot's death in 1945, when his car was bombed by Allied forces, the PPF collapsed, and its members faced severe repercussions for their collaboration with the Nazis. The party's legacy remains a stark example of the existence and influence of fascist movements in France during the interwar and wartime periods.

In summary, the Parti Populaire Français (PPF) was an openly fascist party led by Jacques Doriot that actively allied with the Nazis and promoted their ideology in France. Its collaborationist activities, anti-Semitic policies, and paramilitary tactics marked it as a dangerous and extremist force in French politics. The PPF's history underscores the reality that fascist movements did indeed exist in France, though they ultimately failed to gain widespread support or enduring influence.

Political Parties and Interest Groups: Strengthening or Undermining American Democracy?

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Jeunesses Patriotes: Far-right league with fascist elements, active in the 1920s-1930s

The Jeunesses Patriotes (JP), founded in 1924 by Pierre Taittinger, was one of France's most prominent far-right leagues during the interwar period, exhibiting fascist elements in its ideology, organization, and tactics. Emerging in the aftermath of World War I, the JP capitalized on widespread disillusionment with parliamentary democracy, fears of communism, and a desire to restore national prestige. Taittinger, a World War I veteran and conservative politician, envisioned the JP as a paramilitary force to combat the perceived threats of socialism, communism, and internationalism. The league's rhetoric emphasized nationalism, order, and the defense of traditional French values, aligning it with broader fascist trends in Europe.

The JP's structure and methods were overtly fascist in nature. It operated as a paramilitary organization, with members wearing uniforms and adopting a hierarchical, disciplined framework. The league's street fighters, known as *camelots du roi*, engaged in violent clashes with left-wing groups, particularly during the 1930s. These confrontations, often brutal, aimed to intimidate political opponents and assert the JP's dominance in public spaces. The league's use of direct action and its disdain for democratic institutions mirrored the tactics of fascist movements in Italy and Germany, though it never fully embraced the totalitarian aspirations of those regimes.

Ideologically, the Jeunesses Patriotes blended nationalism, anti-communism, and corporatism, key tenets of fascism. The league advocated for a strong, centralized state and the reorganization of society along corporatist lines, eliminating class conflict through the collaboration of social groups under state authority. While the JP did not explicitly call for a dictatorship, its rejection of parliamentary democracy and its emphasis on authoritarian solutions placed it firmly within the fascist spectrum. Additionally, the league's anti-Semitic rhetoric, particularly after 1933, further aligned it with fascist ideologies, though anti-Semitism was not its primary focus.

The JP's influence peaked in the early 1930s, when it claimed tens of thousands of members and played a significant role in the February 6, 1934, riots, an attempted insurrection against the French government. However, the league's failure to topple the government and its subsequent decline highlighted the limitations of fascist movements in France. Unlike in Italy or Germany, French fascism remained fragmented and unable to seize power. Internal divisions, financial struggles, and the rise of competing far-right groups, such as the Croix-de-Feu, further weakened the JP. By the late 1930s, it had largely dissolved, though its legacy persisted in the broader far-right milieu.

In conclusion, the Jeunesses Patriotes exemplified the fascist elements present within France's interwar far-right leagues. Its paramilitary structure, violent tactics, and authoritarian ideology aligned it with fascism, though it lacked the coherence and mass appeal of its European counterparts. The JP's rise and fall underscore the complexities of fascism in France, where such movements remained marginal despite their radicalism. Studying the JP provides critical insights into the broader question of whether France had fascist political parties, revealing a landscape of extremist groups that, while fascist in many respects, never achieved the dominance seen elsewhere in Europe.

Dual Party Membership in the UK: Legal, Ethical, or Impossible?

You may want to see also

Fascist Influence in Vichy: Collaborationist regime during WWII with fascist characteristics under Pétain

The Vichy regime, established in France following the country's defeat by Nazi Germany in 1940, was a collaborationist government led by Marshal Philippe Pétain. While not a fascist party in the strict sense, the Vichy regime exhibited several fascist characteristics and was heavily influenced by fascist ideologies prevalent in Europe at the time. This influence was evident in its policies, rhetoric, and alignment with Nazi Germany, which sought to impose its own fascist vision on occupied territories. The regime's authoritarian structure, nationalist propaganda, and anti-democratic measures mirrored fascist principles, even though France did not have a dominant fascist party like Italy or Germany.

One of the most significant fascist characteristics of the Vichy regime was its emphasis on national regeneration and authoritarian rule. Pétain's government promoted the idea of a "National Revolution," which aimed to overhaul French society by rejecting liberal democracy, individualism, and parliamentary politics. This revolution sought to create a corporatist state, a key fascist concept, where society was organized into interest groups or corporations under state control. The regime suppressed political opposition, disbanded trade unions, and imposed strict censorship, aligning with fascist ideals of centralized power and the suppression of dissent. These measures were justified under the guise of restoring France's greatness, a narrative common in fascist movements.

The Vichy regime also adopted fascist-inspired social and cultural policies. It promoted traditionalist values, emphasizing the family, religion, and rural life as the foundations of the nation. The regime's anti-Semitic policies, including the enactment of the *Statut des Juifs* (Jewish Statute), which excluded Jews from public life and professions, were influenced by Nazi racial ideology but also resonated with domestic anti-Semitic currents. Additionally, the Vichy government glorified youth organizations, such as the *Jeunesses François*, which were modeled after fascist youth movements and aimed to indoctrinate young people with nationalist and authoritarian ideals.

Collaboration with Nazi Germany was a central aspect of the Vichy regime's fascist influence. Pétain's government willingly cooperated with the occupiers, implementing policies that aligned with Nazi goals, including the persecution of Jews and political opponents. The regime's security forces, such as the *Milice*, worked closely with the Gestapo to hunt down resistance fighters and enforce Nazi decrees. This collaboration went beyond mere compliance, as Vichy officials often took initiative in implementing repressive measures, demonstrating a shared ideological commitment to authoritarianism and racial hierarchy.

While the Vichy regime was not a fascist party in itself, its policies and ideology were deeply influenced by fascist principles. The regime's authoritarianism, nationalism, anti-Semitism, and collaboration with Nazi Germany reflected the broader fascist currents of the era. Although France lacked a mass fascist movement comparable to those in Italy or Germany, the Vichy government's actions during World War II demonstrated how fascist ideas could permeate a collaborationist regime, even in a country with a strong republican tradition. This period remains a stark reminder of the dangers of authoritarianism and the erosion of democratic values under extreme circumstances.

Are Political Parties Mentioned in the Constitution? Exploring the Legal Framework

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, France had several fascist political parties, particularly during the interwar period (1918–1939) and to a lesser extent in the post-World War II era.

Notable fascist parties in France included *Action Française*, *Croix-de-Feu*, *Parti Populaire Français (PPF)*, and *Mouvement Franciste*.

While none achieved dominant power, the *Parti Populaire Français (PPF)* led by Jacques Doriot became the most influential fascist party in the 1930s and collaborated with Nazi Germany during World War II.

French fascist parties often emphasized nationalism, anti-communism, and traditionalist values but lacked the centralized, totalitarian structure of Mussolini’s Italy or Hitler’s Germany.

Yes, many fascist and collaborationist parties were banned or dissolved after World War II, and fascism became largely marginalized in French politics.