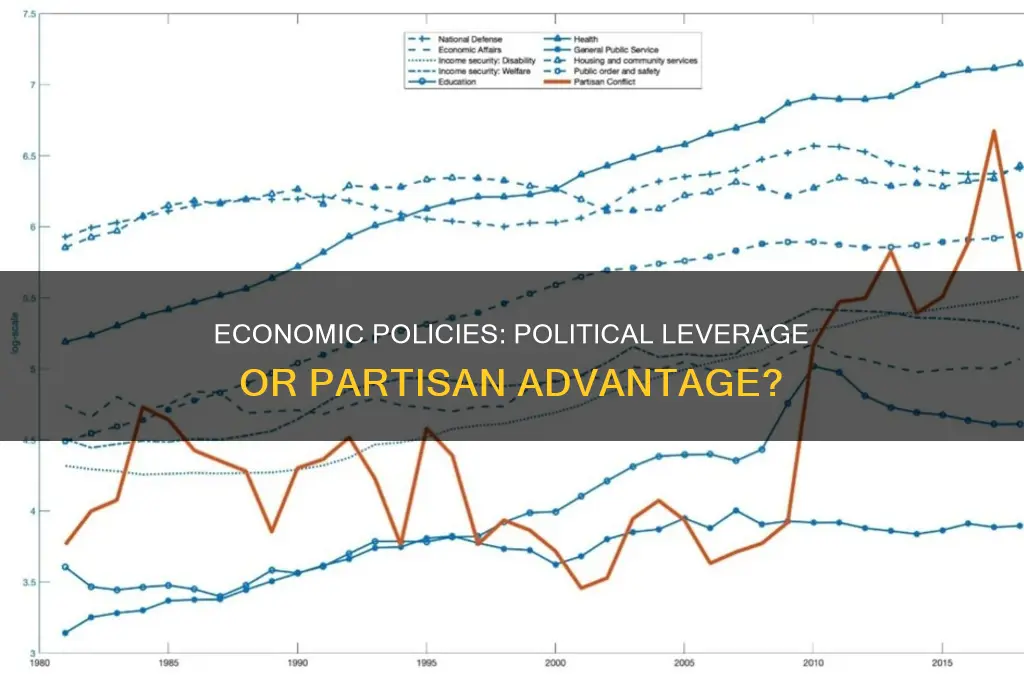

The question of whether economic policies can disproportionately benefit one political party over another is a contentious and multifaceted issue. Economic policies, such as tax reforms, fiscal spending, and regulatory changes, inherently shape the distribution of resources and opportunities within a society. While policymakers often frame these measures as neutral or universally beneficial, their implementation can inadvertently or intentionally favor specific demographic groups, industries, or regions that align more closely with the interests of a particular political party. For instance, tax cuts for high-income earners may bolster support from wealthier constituents who are more likely to back conservative parties, while increased social welfare spending might appeal to lower-income voters traditionally associated with progressive parties. This dynamic raises concerns about fairness, political polarization, and the potential for economic policies to become tools for partisan advantage rather than instruments of broad-based prosperity. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for evaluating the integrity of economic governance and its impact on democratic processes.

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Tax Policies Favoring Specific Income Groups

Tax policies are a powerful tool that can significantly influence the economic well-being of specific income groups, often aligning with the interests of particular political parties. When a government designs tax policies that favor certain income brackets, it can create a strategic advantage for a political party by appealing to its core constituency. For instance, a political party may advocate for lower tax rates on high-income earners, positioning itself as a champion of job creators and investors. This approach not only benefits the wealthy but also reinforces the party’s narrative of promoting economic growth and entrepreneurship. Such policies can solidify support from high-income voters, who are often major donors and influential voices in political campaigns.

Conversely, tax policies can also be tailored to benefit lower- and middle-income groups, which are often the target demographic for more progressive or left-leaning political parties. Measures such as expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), increasing standard deductions, or implementing progressive tax rates can provide financial relief to these groups. By framing these policies as efforts to reduce income inequality and support working families, a political party can strengthen its appeal to a broad base of voters who stand to gain directly from such measures. This strategic use of tax policy not only addresses economic disparities but also fosters political loyalty among beneficiaries.

The design of tax policies can also create divisions that benefit one political party over another by exacerbating or mitigating economic inequalities. For example, a party may push for tax cuts that disproportionately benefit the wealthy while simultaneously reducing funding for social programs that serve lower-income populations. This approach can deepen economic divides, making it easier for the party to portray itself as the protector of its favored income group. Critics may argue that such policies are regressive, but from a political standpoint, they effectively consolidate support from the targeted demographic.

Moreover, the timing and presentation of tax policies can be manipulated to align with political cycles, further benefiting one party over another. For instance, a party in power might implement tax cuts or rebates just before an election, creating a sense of immediate economic benefit for voters. This tactic, often referred to as "election-year economics," can sway public opinion in favor of the incumbent party, regardless of the long-term fiscal implications. Such strategic timing underscores how tax policies can be wielded as political tools rather than purely economic instruments.

In conclusion, tax policies favoring specific income groups are a clear example of how economic measures can be crafted to benefit one political party over another. By targeting tax relief or burdens to particular income brackets, parties can solidify their support base, reinforce their ideological stance, and influence voter behavior. While these policies may address legitimate economic concerns, their design and implementation often reflect political calculations aimed at gaining or maintaining power. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for evaluating the intersection of economics and politics and its impact on societal equity.

Can Citizens Legally Dismantle a Political Party? Exploring the Possibilities

You may want to see also

Government Spending on Partisan Constituencies

The targeting of government spending to partisan constituencies often occurs through discretionary funding programs, where the allocation of resources is not strictly formula-based but rather influenced by political considerations. For example, a ruling party might prioritize funding for projects in swing districts or states where it seeks to gain or maintain a political advantage. This can include investments in roads, schools, healthcare facilities, or other public goods that are highly visible and directly impact voters’ daily lives. By doing so, the party can claim credit for improvements in these areas, effectively using public funds to bolster its electoral prospects.

Another mechanism through which government spending benefits partisan constituencies is via pork-barrel politics, where legislators secure funding for localized projects that primarily benefit their own districts. While these projects may have limited national significance, they are politically valuable as they allow elected officials to demonstrate their ability to deliver resources to their constituents. This practice is particularly common in systems where legislators have significant control over budget allocations, such as in the United States Congress. Critics argue that pork-barrel spending is inefficient and diverts resources from more pressing national priorities, but for the parties involved, it is a strategic tool to maintain and expand their political base.

The impact of such targeted spending is often amplified through strategic communication and messaging. Parties in power frequently highlight their investments in partisan constituencies during campaigns, framing them as evidence of their commitment to the well-being of specific groups or regions. This narrative can be particularly effective in areas where voters feel neglected or economically disadvantaged, as it reinforces the perception that the party understands and addresses their needs. Conversely, opposition parties may criticize such spending as politically motivated and unfair, but they often engage in similar practices when they gain power, perpetuating a cycle of partisan allocation of resources.

However, government spending on partisan constituencies is not without risks. If perceived as overly partisan or inequitable, it can alienate voters in non-beneficiary regions and fuel accusations of favoritism or corruption. This can erode public trust in government institutions and exacerbate regional or social divisions. Additionally, such spending may lead to suboptimal resource allocation, as decisions are driven by political rather than economic or social priorities. Despite these drawbacks, the practice remains widespread because of its effectiveness in securing and maintaining political power, illustrating how economic policies can be wielded as tools for partisan advantage.

China's Political Landscape: One Party Dominance or Hidden Pluralism?

You may want to see also

Regulatory Changes Benefiting Key Industries

Regulatory changes are a powerful tool that can significantly influence the fortunes of specific industries, often aligning with the interests of particular political parties. When a government alters regulations, it can create an environment that favors certain sectors, providing them with a competitive edge and fostering growth. For instance, a political party might advocate for relaxed environmental regulations in the energy sector, benefiting fossil fuel companies. This could involve streamlining permitting processes for oil and gas exploration, reducing emissions standards, or offering tax incentives for traditional energy production. Such policies would likely appeal to industries reliant on these practices and their associated lobbying groups, potentially securing political support and campaign contributions.

In the financial sector, regulatory adjustments can also be strategically employed to advantage specific parties. A political party may propose deregulation, arguing that it stimulates economic growth by reducing compliance burdens on banks and investment firms. This could include rolling back rules on capital requirements, consumer protections, or proprietary trading restrictions. These changes would likely be welcomed by financial institutions, potentially leading to increased political donations and support from Wall Street. Conversely, a different political ideology might favor stricter regulations to prevent another financial crisis, appealing to a different set of voters and interest groups.

The technology industry is another arena where regulatory interventions can be tailored to benefit specific political agendas. A party might introduce policies that favor established tech giants by loosening antitrust regulations, allowing for more aggressive mergers and acquisitions. Alternatively, they could promote tax breaks for research and development, benefiting innovative startups. These moves could secure the support of powerful tech companies and their leaders, who may then advocate for the party's agenda. On the other hand, a competing political ideology might focus on data privacy regulations, appealing to consumers concerned about corporate overreach.

Agriculture is a sector where regulatory changes can have a direct impact on political fortunes. A political party could implement subsidies and price supports for specific crops, benefiting large-scale farmers and agribusinesses. They might also relax environmental regulations related to land use and water rights, appealing to agricultural interests. These policies could secure the loyalty of farming communities and industry associations. Conversely, a different political approach might emphasize sustainable farming practices and local food systems, attracting environmentally conscious voters.

In the healthcare industry, regulatory reforms can be a double-edged sword, offering benefits to various stakeholders depending on the political agenda. A party might push for deregulation, allowing insurance companies and pharmaceutical corporations more freedom in pricing and product offerings. This could result in increased campaign funding from these industries. Alternatively, a different political strategy might involve stricter regulations on drug pricing and insurance mandates, appealing to voters concerned about healthcare accessibility. Each approach would likely garner support from distinct interest groups within the healthcare sector.

These examples illustrate how regulatory changes can be strategically crafted to benefit key industries, thereby influencing political outcomes. By tailoring policies to favor specific sectors, political parties can secure powerful allies, financial support, and voter loyalty. However, such targeted regulatory interventions also carry the risk of creating an uneven playing field, potentially leading to market distortions and public backlash. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for comprehending the intricate relationship between economic policies and political power.

Exploring Viable Third Political Parties in U.S. States Today

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Campaign Finance and Corporate Influence

The relationship between campaign finance and corporate influence is a critical aspect of understanding how economic policies can disproportionately benefit one political party over another. In many democratic systems, political campaigns rely heavily on funding from corporations, wealthy individuals, and special interest groups. This financial support often comes with implicit or explicit expectations that the supported party will advance policies favorable to the donors' economic interests. For instance, corporations may fund political parties that advocate for lower taxes, deregulation, or trade policies that enhance their profitability. This dynamic can skew economic policies in favor of the donor class, often at the expense of broader societal welfare.

Corporate influence in campaign finance is particularly pronounced in systems with lax regulations on political donations. In such environments, corporations and wealthy donors can contribute vast sums of money through political action committees (PACs), super PACs, or direct donations, effectively amplifying their voice in the political process. This disproportionate influence can lead to policies that prioritize corporate profits over public goods like healthcare, education, or environmental protection. For example, a party heavily funded by the fossil fuel industry might oppose green energy policies, even if they are in the long-term interest of the nation, to protect the financial interests of its donors.

The impact of corporate influence on campaign finance is further exacerbated by the revolving door phenomenon, where individuals move between high-ranking corporate positions and government roles. This interchange creates a symbiotic relationship where policymakers are incentivized to craft laws that benefit their future or past employers. As a result, economic policies may be designed to favor specific industries or corporations, providing them with unfair advantages such as subsidies, tax breaks, or favorable regulatory treatment. This not only distorts market competition but also undermines the principle of equitable governance.

Moreover, the opacity of campaign financing in many countries allows corporations to exert influence without public scrutiny. Dark money, or funds from undisclosed sources, enables corporations and special interests to shape political narratives and outcomes without accountability. This lack of transparency can lead to policies that appear to serve the public interest but are, in reality, designed to benefit a narrow set of corporate stakeholders. For instance, a policy marketed as job creation might primarily serve to enrich a few corporations while neglecting broader employment needs.

To mitigate the disproportionate influence of corporate financing on economic policies, reforms such as stricter campaign finance regulations, public funding of elections, and enhanced transparency are essential. Such measures can level the playing field, ensuring that economic policies are crafted to benefit the entire population rather than a select few. Without these reforms, the cycle of corporate-driven policy-making will continue to benefit one political party—typically the one aligned with corporate interests—at the expense of balanced and equitable governance. This imbalance not only undermines democratic integrity but also perpetuates economic inequality and stifles inclusive growth.

Are Political Parties Losing Their Grip on Power?

You may want to see also

Redistricting and Economic Resource Allocation

Redistricting, the process of redrawing electoral district boundaries, is a powerful tool that can significantly influence the distribution of political power. When combined with economic resource allocation, it becomes a strategic mechanism through which one political party can gain a substantial advantage over another. The way districts are redrawn can determine which communities receive economic benefits, such as infrastructure investments, job creation programs, or federal funding. For instance, a party in control of redistricting may consolidate its voter base in specific districts while diluting the influence of opposition voters in others. This gerrymandering not only skews political representation but also ensures that economic resources are disproportionately allocated to areas that favor the dominant party, reinforcing its electoral and economic stronghold.

Economic resource allocation plays a critical role in this dynamic, as it often follows the contours of political power. When a party controls both redistricting and economic policy, it can direct funding and development projects to districts that support its agenda. For example, infrastructure projects like highways, schools, or industrial zones may be prioritized in districts that are politically aligned with the ruling party, while opposition-leaning areas are neglected. This targeted allocation of resources not only boosts the local economy in favorable districts but also strengthens the party's popularity and voter loyalty in those regions. Over time, this creates a feedback loop where economic prosperity in certain areas becomes synonymous with political support for the dominant party.

The interplay between redistricting and economic resource allocation is further exacerbated by the control of legislative bodies. The party in power can pass economic policies that favor its redrawn districts, such as tax incentives, subsidies, or grants. These policies are often framed as broadly beneficial but are strategically designed to maximize impact in districts crucial for maintaining political control. Conversely, districts that oppose the ruling party may face reduced funding, stricter regulations, or exclusion from economic development initiatives. This deliberate economic marginalization weakens the opposition's ability to compete politically, as their constituents experience slower growth and fewer opportunities.

Moreover, redistricting can influence the representation of marginalized communities, which in turn affects how economic resources are allocated. When a party redraws districts to dilute the voting power of minority or low-income groups, it simultaneously reduces their ability to advocate for equitable economic policies. As a result, these communities often receive fewer investments in education, healthcare, and job creation, perpetuating economic disparities. This systemic disadvantage not only benefits the dominant party by minimizing opposition but also ensures that economic resources remain concentrated in areas that align with its political interests.

In conclusion, redistricting and economic resource allocation are intertwined mechanisms that can be manipulated to benefit one political party over another. By controlling the redistricting process, a party can shape the political landscape to its advantage, while strategic economic policies further solidify its power. This combination creates an uneven playing field where political and economic resources are distributed in ways that favor the ruling party, often at the expense of fair representation and equitable development. Understanding this dynamic is crucial for addressing the broader question of whether economic policies can be wielded to benefit one political party over another, as redistricting serves as a foundational tool in this strategic imbalance.

Bipartisan Political Committees: Do Both Parties Collaborate in Governance?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, economic policies can disproportionately benefit one political party depending on their alignment with the party’s core constituencies or ideological priorities. For example, tax cuts for high-income earners may favor a conservative party, while increased social spending may benefit a liberal party.

Not always. The political impact of economic policies depends on their effectiveness, public perception, and timing. If policies fail to deliver promised outcomes or are perceived as unfair, they can backfire and harm the ruling party’s electoral prospects.

Yes, opposition parties often critique economic policies to highlight their shortcomings or inequities, framing them as benefiting the ruling party’s base at the expense of others. This strategy can help opposition parties mobilize support and gain political advantage.