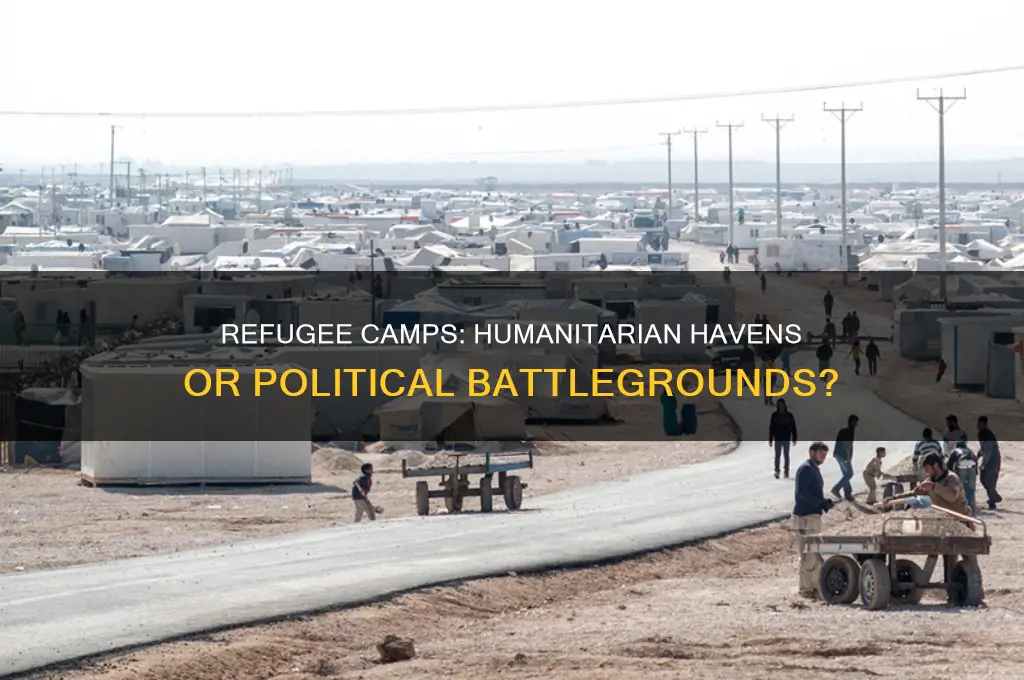

Refugee camps, often perceived as purely humanitarian spaces, are deeply intertwined with political dynamics that shape their existence, management, and impact. While their primary purpose is to provide shelter and aid to displaced populations fleeing conflict, persecution, or disaster, these camps are frequently influenced by the geopolitical interests of host countries, international organizations, and donor states. The location, funding, and operational control of camps can reflect political agendas, such as containing refugee movements, exerting influence over conflict zones, or leveraging humanitarian aid for diplomatic leverage. Additionally, the prolonged nature of many refugee crises often transforms camps into semi-permanent settlements, raising questions about governance, rights, and the political agency of refugees themselves. Thus, refugee camps are not neutral spaces but rather complex arenas where humanitarian needs intersect with political strategies, power struggles, and global policies.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Political Instrumentalisation | Refugee camps are often used as tools by host governments or international actors to achieve political goals, such as leveraging aid for diplomatic gains or controlling refugee movements. |

| State Sovereignty | Camps are established within the territory of host countries, making them subject to the political and legal frameworks of those states, which can influence camp management and refugee rights. |

| Security and Control | Governments and authorities use camps to monitor and control refugee populations, often citing security concerns, which can lead to restrictions on movement and political activities. |

| Humanitarian vs. Political Interests | The humanitarian nature of camps is often overshadowed by political interests, with aid distribution and camp conditions influenced by political agendas rather than purely humanitarian needs. |

| International Politics | Refugee camps are often at the center of international political debates, with donor countries and organizations using them as bargaining chips in global negotiations. |

| Refugee Agency and Resistance | Refugees within camps may engage in political activities or resistance against host governments, leading to tensions and further politicization of the camp environment. |

| Long-Term Dependency | Prolonged stays in camps can create political dependency, as refugees become reliant on host countries and international aid, limiting their ability to advocate for their rights. |

| Geopolitical Location | The location of refugee camps is often politically strategic, influenced by regional conflicts, border disputes, and the interests of neighboring states. |

| Resource Competition | Camps can become sites of political tension due to competition over limited resources, leading to conflicts between refugees, host communities, and authorities. |

| Legal and Policy Frameworks | The political status of refugee camps is shaped by international laws (e.g., the 1951 Refugee Convention) and national policies, which vary widely and can be manipulated for political ends. |

Explore related products

$43.41 $64.95

$28.45 $29.95

What You'll Learn

- State Sovereignty vs. Humanitarian Aid: Tension between host nations' control and international aid organizations' interventions

- Camp Governance Structures: Power dynamics within camps, including leadership roles and decision-making processes

- International Aid Politics: Geopolitical interests influencing funding, resource allocation, and camp management

- Refugee Agency & Resistance: How refugees navigate political constraints and assert their rights within camps

- Camps as Political Tools: Use of camps by states or groups to achieve political or strategic goals

State Sovereignty vs. Humanitarian Aid: Tension between host nations' control and international aid organizations' interventions

Refugee camps, often perceived as apolitical spaces of humanitarian need, are deeply entangled in the political dynamics of state sovereignty and international intervention. Host nations, burdened by the influx of displaced populations, assert their authority to control camp operations, security, and resource allocation. Simultaneously, international aid organizations, driven by humanitarian imperatives, seek to deliver aid independently, often challenging the host state’s regulatory frameworks. This tension is not merely administrative; it reflects competing priorities—national security versus universal human rights—that shape the lived realities of refugees.

Consider the case of Kenya’s Dadaab camp, once the largest refugee complex in the world. In 2016, the Kenyan government threatened to close the camp, citing national security concerns and the economic strain on local resources. International aid organizations, including the UNHCR, countered that closure would violate international humanitarian law and leave hundreds of thousands of Somali refugees vulnerable. This standoff illustrates the friction between a state’s right to protect its borders and the humanitarian community’s duty to provide lifesaving assistance. Host nations often view prolonged refugee presence as a threat to their sovereignty, while aid organizations prioritize the principle of non-refoulement, creating a deadlock that exacerbates refugee suffering.

To navigate this tension, a multi-stakeholder approach is essential. Host nations must be included as equal partners in humanitarian planning, ensuring their security and developmental concerns are addressed. For instance, in Jordan, the government collaborated with UNHCR to implement the Jordan Compact, which linked humanitarian aid to long-term development goals, such as job creation for both refugees and host communities. This model demonstrates that integrating humanitarian interventions into national policies can alleviate sovereignty concerns while meeting refugee needs. However, such partnerships require trust-building and a willingness to compromise, which are often hindered by political mistrust and bureaucratic inertia.

A critical caution: overemphasis on state sovereignty can lead to the weaponization of humanitarian aid. In countries like Myanmar and Syria, governments have restricted access to aid organizations, using humanitarian assistance as a bargaining chip in political conflicts. Conversely, unchecked international intervention can undermine local governance, fostering dependency and resentment. Striking a balance requires clear, context-specific frameworks that respect sovereignty while ensuring humanitarian access. For example, the UN’s Humanitarian Response Plans should incorporate host nation priorities, such as infrastructure development or education reforms, to align aid with national interests.

Ultimately, the tension between state sovereignty and humanitarian aid is not irreconcilable. By fostering dialogue, leveraging shared goals, and adopting flexible strategies, host nations and aid organizations can transform refugee camps from sites of political contention into models of collaborative governance. The key lies in recognizing that humanitarian action is inherently political—and that its success depends on navigating this complexity with empathy, pragmatism, and respect for all stakeholders.

Are Pirates Polite? Discover the Charming Book Trailer Adventure

You may want to see also

Camp Governance Structures: Power dynamics within camps, including leadership roles and decision-making processes

Refugee camps, often perceived as temporary shelters, evolve into complex societies with intricate governance structures. These structures are not merely administrative frameworks but are deeply political, reflecting power dynamics, leadership struggles, and decision-making processes that mirror broader societal hierarchies. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for anyone involved in humanitarian aid, policy-making, or academic research.

Consider the formation of leadership roles within camps. In many cases, leaders emerge organically, often based on pre-existing social statuses, such as tribal elders, religious figures, or former government officials. For instance, in the Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya, traditional Dinka chiefs from South Sudan continue to exert authority, mediating disputes and representing their communities in negotiations with aid agencies. However, this informal leadership can marginalize newer arrivals or minority groups, creating power imbalances that perpetuate inequality. Aid organizations sometimes formalize these roles by appointing camp committees, but this process often favors those already in power, reinforcing existing hierarchies rather than democratizing governance.

Decision-making processes within camps further highlight their political nature. While humanitarian agencies like the UNHCR or NGOs technically hold authority, practical decisions often involve negotiation with camp leaders. For example, the distribution of food rations or the allocation of shelter materials frequently requires the approval of local leaders, who may prioritize their own communities or demand personal benefits. This dynamic can lead to corruption, as seen in the Zaatari camp in Jordan, where some leaders were accused of hoarding resources. Conversely, in the Cox’s Bazar camps in Bangladesh, Rohingya leaders collaborated with aid agencies to establish more transparent systems, demonstrating that power dynamics can be reshaped through inclusive governance models.

A comparative analysis reveals that camps with participatory governance structures tend to be more stable and equitable. In the Azraq camp in Jordan, residents were involved in designing camp layouts and service delivery systems, reducing tensions and fostering a sense of ownership. However, such models require significant time and resources, which are often lacking in emergency situations. Moreover, participatory approaches can be manipulated by dominant groups, as seen in the Dadaab camp in Kenya, where certain clans dominated community meetings, sidelining women and youth. This underscores the need for external actors to actively promote inclusivity and accountability in camp governance.

To navigate these complexities, humanitarian actors must adopt a nuanced approach. First, conduct thorough socio-political assessments to understand existing power structures before formalizing leadership roles. Second, establish clear accountability mechanisms, such as regular audits and feedback systems, to prevent corruption. Third, prioritize the representation of marginalized groups, including women, youth, and minorities, in decision-making processes. For instance, in the Mae La camp in Thailand, women’s committees were formed to address gender-based violence, significantly improving safety and empowerment. Finally, invest in capacity-building programs to equip camp residents with leadership and negotiation skills, ensuring sustainable governance structures. By addressing these dynamics, camps can become less political battlegrounds and more equitable communities.

Mastering Open Political Conversations: Tips for Respectful and Productive Dialogue

You may want to see also

International Aid Politics: Geopolitical interests influencing funding, resource allocation, and camp management

Refugee camps, often perceived as apolitical spaces of humanitarian need, are deeply entangled in the web of international aid politics. Geopolitical interests wield significant influence over funding decisions, resource allocation, and camp management, shaping the lives of millions of displaced individuals. This dynamic is not merely a byproduct of global power structures but a deliberate strategy employed by states and organizations to advance their agendas.

Consider the Syrian refugee crisis, where camps in neighboring countries like Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey became battlegrounds for geopolitical influence. Western nations, eager to contain the crisis within the region, provided substantial funding to these host countries, effectively outsourcing their responsibilities. However, this aid was often contingent on political alignments, with countries like Turkey leveraging their strategic position to negotiate better deals with the European Union. Meanwhile, camps in less geopolitically significant areas, such as those in North Africa, received disproportionately less attention, leaving refugees in dire conditions.

The allocation of resources within camps further illustrates the political nature of aid. In many instances, essential services like healthcare, education, and food distribution are prioritized based on donor preferences rather than actual needs. For example, during the Rohingya crisis in Bangladesh, international donors focused heavily on building infrastructure and security measures, partly to appease the Bangladeshi government and maintain regional stability. While these investments were necessary, they often overshadowed critical humanitarian needs like mental health services and vocational training, which were deemed less politically expedient.

Camp management itself is another arena where geopolitical interests play out. Host countries frequently exert control over camp operations, using them as tools to assert sovereignty or manage international relations. In Kenya’s Dadaab camp, the government has repeatedly threatened closure, citing security concerns, but also leveraging the camp’s presence to negotiate aid and political support from Western nations. Similarly, in Uganda, the government’s relatively open-door policy toward refugees has been praised internationally, but it also serves as a diplomatic asset, positioning Uganda as a regional leader in humanitarian response.

To navigate this complex landscape, humanitarian organizations must adopt a dual strategy. First, they should advocate for needs-based funding models that prioritize the most vulnerable populations, regardless of geopolitical considerations. Second, they must engage in transparent dialogue with donors and host governments to mitigate political interference in camp management. For instance, implementing independent monitoring systems can ensure that resources are allocated equitably and that camp policies align with international humanitarian standards.

In conclusion, the politics of international aid are inextricably linked to the operation of refugee camps. By recognizing and addressing the influence of geopolitical interests, stakeholders can work toward more just and effective humanitarian responses. This requires not only systemic reforms but also a commitment to placing the dignity and rights of refugees at the forefront of decision-making.

Is the NRA a Political Group? Uncovering Its Influence and Agenda

You may want to see also

Explore related products

$43.44 $54.99

$24.44 $26.5

Refugee Agency & Resistance: How refugees navigate political constraints and assert their rights within camps

Refugee camps, often perceived as apolitical spaces of humanitarian aid, are in fact deeply political environments where power dynamics, external influences, and internal hierarchies shape daily life. Within these constraints, refugees exercise agency and resistance, challenging the systems that marginalize them while asserting their rights. This dynamic is not merely reactive but strategic, as individuals and communities navigate complex political landscapes to reclaim autonomy and dignity.

Consider the case of the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan, where Syrian refugees have developed informal governance structures to address gaps in official services. Through community-led initiatives, such as women’s cooperatives and youth-run media platforms, residents bypass bureaucratic inefficiencies and assert their ability to self-organize. These actions are not just practical solutions but acts of resistance against the dehumanizing narrative that refugees are passive recipients of aid. By creating their own systems, they challenge the political and humanitarian frameworks that often treat them as temporary, voiceless entities.

To understand how refugees navigate political constraints, it’s instructive to examine their use of collective action. In camps like Dadaab in Kenya, residents have staged protests and boycotts to demand better living conditions and political representation. These actions are risky, as they often provoke backlash from host governments or aid agencies. Yet, refugees strategically leverage international attention, using social media and global networks to amplify their grievances. For instance, during the 2016 threat of closure of Dadaab, refugees organized campaigns that highlighted the legal and moral obligations of the international community, forcing a reevaluation of the decision.

A comparative analysis reveals that resistance takes different forms depending on the political context. In camps under authoritarian regimes, refugees often adopt covert strategies, such as underground education networks or coded communication, to avoid repression. In contrast, in more democratic settings, they may engage in open advocacy, lobbying for policy changes or legal reforms. For example, Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh have used art and storytelling to document their experiences, preserving their identity and challenging the erasure of their history. These methods are not just acts of survival but deliberate political statements that assert their humanity and rights.

Practically, refugees can enhance their agency by forming alliances with external actors, such as NGOs, journalists, or diaspora communities. These partnerships provide resources, legal support, and platforms for advocacy. For instance, in the Calais Jungle in France, refugees collaborated with international activists to challenge evictions and demand safe passage. Such coalitions amplify their voices and create pressure points for political change. However, refugees must also be cautious of exploitation, ensuring that external actors respect their leadership and priorities.

In conclusion, refugee agency and resistance within camps are multifaceted and deeply political. By self-organizing, mobilizing collectively, and forming strategic alliances, refugees challenge the structures that confine them. Their actions are not just responses to adversity but affirmations of their right to shape their own futures. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for anyone seeking to support refugee communities, as it highlights the importance of recognizing and amplifying their inherent agency.

Mastering the Art of Political Engagement: A Beginner's Guide

You may want to see also

Camps as Political Tools: Use of camps by states or groups to achieve political or strategic goals

Refugee camps, often perceived as temporary shelters for displaced populations, can serve as potent political tools in the hands of states or groups with strategic agendas. By controlling resources, movement, and narratives within these camps, actors can manipulate humanitarian crises to consolidate power, exert influence, or delegitimize opponents. For instance, during the Syrian conflict, both the Assad regime and opposition groups have used camps to control access to aid, effectively weaponizing humanitarian assistance to reward loyalty or punish dissent. This tactic not only deepens dependency on the controlling entity but also shapes the political allegiances of vulnerable populations.

Consider the steps through which camps are transformed into political instruments. First, localization of control: states or groups establish administrative dominance over camps, often by positioning their own personnel or proxies as gatekeepers. Second, resource allocation as leverage: aid distribution is strategically directed to favor certain groups, fostering divisions and dependencies. Third, narrative manipulation: controlling communication within and about the camp allows actors to frame the crisis in ways that align with their political objectives. For example, in Myanmar, the military junta has used Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh to propagate narratives of ethnic conflict, diverting international attention from their own human rights abuses.

Caution must be exercised when analyzing the political use of camps, as their dual nature—both humanitarian necessity and potential tool of oppression—complicates responses. Humanitarian organizations often face dilemmas when operating in such environments, risking co-optation into political agendas. A practical tip for aid workers is to maintain rigorous neutrality and transparency in operations, documenting and reporting any attempts at politicization. Additionally, international bodies must prioritize independent monitoring of camps to prevent their exploitation for political gain.

Comparatively, the use of camps as political tools is not limited to conflict zones. In Europe, the establishment of migrant detention centers has been criticized as a means to deter migration and bolster nationalist agendas. These facilities, often characterized by harsh conditions and restricted access, serve as visible symbols of a state’s commitment to border control, reinforcing political narratives of security and sovereignty. Such examples underscore the versatility of camps as instruments of political strategy, adaptable to diverse contexts and objectives.

In conclusion, the politicization of refugee camps represents a critical yet underacknowledged dimension of modern conflict and governance. By understanding the mechanisms through which camps are weaponized—control, resource manipulation, and narrative shaping—stakeholders can develop more effective strategies to mitigate their misuse. Ultimately, the challenge lies in balancing the immediate humanitarian needs of displaced populations with the long-term goal of safeguarding their political autonomy and dignity.

Mastering Manners: How Polite Are You in Daily Interactions?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, refugee camps are inherently political because they are often established in response to political conflicts, such as wars, persecution, or human rights violations, and their existence reflects the failure of political systems to protect civilians.

Host countries’ political agendas can shape the location, funding, and management of refugee camps, often prioritizing national security, economic interests, or diplomatic relations over the needs of refugees.

Yes, refugee camps can be used as political tools by host countries, donor nations, or international organizations to exert pressure on the countries of origin or to gain diplomatic advantages.

Refugee camps often become spaces for political activism, where refugees organize to demand rights, advocate for repatriation, or resist policies that restrict their freedoms.

International politics, including donor funding, geopolitical interests, and global policies, significantly influence the resources, security, and humanitarian conditions within refugee camps.