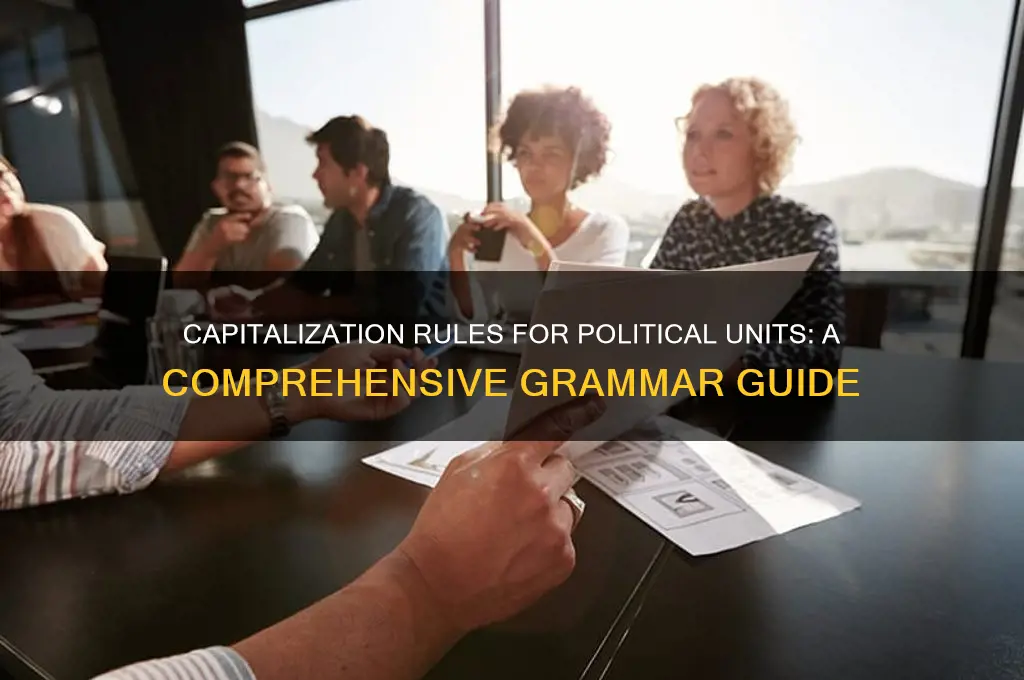

The question of whether political units should be capitalized is a nuanced aspect of writing and editing, often governed by specific style guides and conventions. Political units, such as countries, states, cities, and government bodies, are typically capitalized when referred to as proper nouns, but the rules can vary depending on context and the style guide being followed. For instance, while United States is always capitalized, terms like government or state may be lowercase when used generically. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for maintaining consistency and professionalism in written communication, particularly in academic, journalistic, or official documents.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| General Rule | Political units (e.g., countries, states, cities) are capitalized when used as proper nouns. |

| Countries | Always capitalized (e.g., United States, Canada). |

| States/Provinces | Capitalized when part of a formal name (e.g., California, Ontario). |

| Cities/Towns | Always capitalized (e.g., New York, Paris). |

| Nationalities/Adjectives | Capitalized when referring to people or things (e.g., American, French). |

| Political Parties | Capitalized (e.g., Democratic Party, Republican Party). |

| Government Bodies | Capitalized when official names (e.g., Congress, Parliament). |

| Geographical Regions | Capitalized if proper nouns (e.g., Midwest, Southeast Asia). |

| Common Noun Usage | Not capitalized when used generically (e.g., "the state of Texas" vs. "a state"). |

| Languages | Capitalized (e.g., English, Spanish). |

| Historical Events | Capitalized if proper names (e.g., World War II, American Revolution). |

| Organizations | Capitalized if formal names (e.g., United Nations, NATO). |

| Exceptions | Follow specific style guides (e.g., AP Style, Chicago Manual of Style) for variations. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- General Rule for Capitalization: Political units like countries, cities, and states are capitalized

- Exceptions to Capitalization: Common nouns in political titles (e.g., president) are not capitalized

- Geographical Features: Capitalize named regions (e.g., Midwest) but not directions (e.g., south)

- Organizations and Parties: Political parties and organizations (e.g., Democratic Party) are capitalized

- Historical Events: Capitalize specific events (e.g., American Revolution) but not general terms (e.g., war)

General Rule for Capitalization: Political units like countries, cities, and states are capitalized

Political units, such as countries, cities, and states, are capitalized as a matter of standard grammatical convention. This rule applies universally in English writing, ensuring clarity and consistency. For instance, "France" is always capitalized, as is "Paris" or "California." This practice distinguishes proper nouns from common nouns, preventing confusion between a general term like "city" and a specific entity like "New York City."

The rationale behind capitalizing political units is rooted in their status as unique, named entities. Unlike generic terms, these names refer to specific places with distinct identities. Capitalization serves as a visual cue, signaling to the reader that the word represents a particular country, city, or state. For example, "state" as a common noun refers to a condition or a government structure, whereas "State" with a capital "S" often denotes a specific U.S. state, such as "The State of Texas."

While the general rule is straightforward, exceptions and nuances exist. For example, when referring to a direction or a general area rather than a specific place, capitalization is not used. One would write "southern France" but "the South of France" if referring to the region as a proper noun. Similarly, plural forms like "the Carolinas" are capitalized, but descriptive phrases like "the Midwest" may or may not be, depending on style guides.

Practical application of this rule requires attention to detail. Writers should consult reliable style guides, such as the Chicago Manual of Style or AP Stylebook, for specific cases. For instance, the AP Stylebook advises capitalizing "federal government" when referring to the U.S. government but not when used generically. Consistency is key; once a capitalization style is chosen, it should be applied uniformly throughout a document to maintain professionalism and readability.

In educational settings, teaching this rule involves reinforcing the distinction between proper and common nouns. Exercises like identifying and correcting capitalization errors in sentences can help students internalize the rule. For instance, "I visited paris last summer" should be corrected to "I visited Paris last summer." By emphasizing the importance of capitalization in clarity and precision, educators can equip learners with a fundamental skill for effective communication.

Is C-SPAN Biased? Analyzing Political Neutrality in Media Coverage

You may want to see also

Exceptions to Capitalization: Common nouns in political titles (e.g., president) are not capitalized

In the realm of political writing, a subtle yet significant rule governs the capitalization of titles: common nouns within political designations, such as "president," "governor," or "senator," remain in lowercase when used generically. This convention distinguishes between the role itself and the specific individual holding it. For instance, one would write "President Biden" (capitalized, as it refers to the person) but "the president of the United States" (lowercase, as it describes the position generically). This practice ensures clarity and adheres to standard grammatical principles.

Consider the practical application of this rule in everyday writing. If drafting a news article, referring to "Prime Minister Trudeau" requires capitalization because it identifies the current holder of the office. However, discussing the duties of "a prime minister" in a general sense keeps the term lowercase. This distinction extends to other political roles, such as "chancellor," "mayor," or "ambassador," where capitalization depends on whether the term is tied to a specific individual or used broadly. Mastering this nuance elevates the precision of political discourse.

A comparative analysis reveals why this exception exists. Unlike proper nouns, which always demand capitalization (e.g., "France," "United Nations"), common nouns in political titles follow the same rules as other generic terms. For example, "teacher" remains lowercase unless part of a specific title like "Professor Smith." Similarly, "president" aligns with this logic, avoiding unnecessary capitalization when not tied to a particular person. This consistency mirrors broader grammatical norms, reinforcing the idea that capitalization signals specificity.

To implement this rule effectively, follow these steps: first, identify whether the term refers to a specific individual or the role in general. Second, capitalize only when the term directly precedes a name or clearly identifies a unique holder of the office. Third, maintain lowercase for generic references, even if the context involves politics. For instance, "The vice president will attend the meeting" (lowercase, generic) versus "Vice President Harris will attend the meeting" (capitalized, specific). Adhering to these guidelines ensures grammatical accuracy and professional clarity.

In conclusion, the exception to capitalization for common nouns in political titles serves both grammatical and practical purposes. It maintains consistency with broader language rules while preventing confusion between the role and the individual. By applying this principle thoughtfully, writers can enhance the precision and professionalism of their political discourse. Whether crafting a formal report or a casual blog post, this subtle distinction makes a notable difference in clarity and correctness.

Don't Look Up: A Satirical Mirror on Political Apathy and Crisis

You may want to see also

Geographical Features: Capitalize named regions (e.g., Midwest) but not directions (e.g., south)

Named geographical regions demand capitalization when they function as proper nouns, distinguishing them from generic directions. For instance, "Midwest" is capitalized because it refers to a specific, recognized area of the United States, while "south" remains lowercase when used as a compass direction. This rule ensures clarity and consistency in writing, preventing confusion between a named region and a general orientation. Editors and writers must remain vigilant to this distinction, especially in contexts where precision is critical, such as academic papers, news articles, or travel guides.

The rationale behind this rule lies in the nature of proper nouns versus common nouns. Proper nouns identify unique entities, warranting capitalization to set them apart. For example, "The Great Plains" is capitalized because it denotes a distinct geographical feature, whereas "plains" in a general sense remains lowercase. Directions like "north," "east," "south," and "west" are common nouns unless they are part of a named region, such as "West Coast" or "Eastern Europe." Understanding this distinction is essential for maintaining grammatical accuracy and professional credibility.

Practical application of this rule requires attention to context. For instance, in a sentence like "She moved to the Midwest last year," "Midwest" is capitalized because it refers to the specific region. However, in "She prefers to live in the south of the country," "south" is lowercase because it indicates a direction rather than a named area. Writers should also note that when a direction is part of a formal title or name, it is capitalized, as in "South Africa" or "North Dakota." This nuanced approach ensures that geographical references are both accurate and stylistically correct.

To reinforce this practice, consider using style guides like the *Chicago Manual of Style* or *AP Stylebook*, which provide clear directives on capitalization. For example, the *AP Stylebook* explicitly advises capitalizing named regions and formal directions within titles but not generic directions. Additionally, writers can employ tools like grammar checkers or editorial checklists to catch inconsistencies. By adhering to these guidelines, writers can elevate the quality of their work, ensuring that geographical features are treated with the precision they deserve.

Crafting Impact: A Guide to Designing Political Armbands

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Organizations and Parties: Political parties and organizations (e.g., Democratic Party) are capitalized

Political parties and organizations are the backbone of democratic systems, and their names are not just labels—they are brands. Capitalization of these names is a standard practice in English writing, serving both grammatical and functional purposes. For instance, the "Democratic Party" and the "Republican Party" are always capitalized because they are proper nouns, referring to specific entities. This rule extends to international parties like the "Conservative Party" in the UK or the "Christian Democratic Union" in Germany. The capitalization distinguishes these formal organizations from generic references to democrats, republicans, or conservatives in a broader, non-specific sense.

When writing about political parties, consistency is key. Style guides such as the *Associated Press (AP) Stylebook* and the *Chicago Manual of Style* explicitly instruct writers to capitalize the names of political parties and organizations. This ensures clarity and professionalism in communication. For example, writing "the democratic party" in lowercase would be incorrect because it implies a general group of democrats rather than the official Democratic Party. Similarly, "the Green Party" is capitalized to differentiate it from a generic group of environmental advocates. This practice is not arbitrary; it aligns with the broader rule of capitalizing proper nouns, which include names of specific groups, institutions, and entities.

Capitalization also carries symbolic weight. Political parties invest heavily in their branding, and proper capitalization respects their identity. Imagine referring to "the labor party" instead of "the Labour Party" in the UK—it would undermine the party’s established name and confuse readers. This is especially critical in journalism and academic writing, where accuracy and precision are paramount. For instance, when discussing the "African National Congress" in South Africa, capitalization signals its formal status as a political organization rather than a casual grouping of individuals with similar views.

Practical tips for writers include verifying the official name of a political party or organization before drafting. Many parties have specific naming conventions, such as the "Liberal Democratic Party" in Japan or the "National Front" in France. Additionally, when in doubt, consult a reliable style guide or the party’s official website. For instance, the "Libertarian Party" in the U.S. is always capitalized, but "libertarian principles" remain in lowercase. This distinction ensures that your writing is both grammatically correct and respectful of the organization’s identity. By adhering to these rules, writers maintain credibility and avoid unintentional misrepresentations.

Is Conventional Political Theory Truly Neutral? Exploring Bias and Influence

You may want to see also

Historical Events: Capitalize specific events (e.g., American Revolution) but not general terms (e.g., war)

In the realm of historical writing, the capitalization of events is a nuanced task that demands precision. Specific historical events, such as the American Revolution or the Industrial Revolution, are capitalized to distinguish them as unique, well-defined occurrences. This practice aligns with the broader rule of capitalizing proper nouns, ensuring clarity and consistency in academic and journalistic contexts. Conversely, general terms like "war" or "revolution" remain lowercase when used broadly, as they describe categories rather than singular events.

Consider the French Revolution versus "a revolution in technology." The former is a specific event with a defined timeframe and impact, warranting capitalization. The latter, however, refers to a general concept and thus remains lowercase. This distinction is crucial for writers to avoid ambiguity. For instance, referring to "the Civil War" in an American context immediately identifies the specific conflict (1861–1865), whereas "civil war" in lowercase could apply to any internal conflict globally.

When writing about historical events, follow this rule of thumb: if the event has a universally recognized name and scope, capitalize it. For example, the Holocaust is always capitalized due to its specific historical significance, while "genocide" remains lowercase as a general term. This approach ensures that readers can easily identify the event being discussed without confusion. If unsure, consult reputable style guides like *The Chicago Manual of Style* or *AP Stylebook* for event-specific capitalization rules.

A practical tip for writers is to maintain a list of capitalized historical events relevant to their work. For instance, a historian focusing on 20th-century conflicts might include the Korean War, Vietnam War, and Cold War on their list. This practice not only aids consistency but also reinforces the writer’s authority on the subject. Conversely, avoid capitalizing events that lack widespread recognition or are still being defined, as this can confuse readers or appear pretentious.

In conclusion, capitalizing historical events is a deliberate act that enhances clarity and precision in writing. By distinguishing between specific events and general terms, writers can effectively communicate their ideas while adhering to established conventions. Whether crafting academic papers, journalistic articles, or historical narratives, this rule ensures that the past is presented with the accuracy and respect it deserves.

Launch Your Political Blog: Essential Steps for Impactful Advocacy

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Yes, the names of political units such as countries, states, and cities are always capitalized when used as proper nouns (e.g., Canada, Texas, Paris).

Yes, when "state" is part of the formal name of a political unit, it should be capitalized (e.g., the State of California).

Yes, adjectives derived from proper nouns, including political units, are capitalized (e.g., American, French, Mexican).

No, generic terms like "government" or "parliament" are not capitalized unless they are part of a formal name (e.g., the Government of Canada, the Parliament of the United Kingdom).