The question of whether political beliefs are heritable has sparked considerable debate across disciplines, blending genetics, psychology, and political science. Research suggests that while environmental factors like upbringing and socioeconomic status play a significant role in shaping political ideologies, genetic influences may also contribute to individual differences in political attitudes. Twin studies and behavioral genetic analyses have found that traits such as conservatism, liberalism, and attitudes toward authority or social welfare have a heritable component, though the extent of this influence remains modest. These findings do not imply that political beliefs are predetermined by genes but rather highlight the complex interplay between genetic predispositions and environmental experiences in shaping one's political worldview. This intersection of nature and nurture continues to challenge our understanding of how deeply rooted political inclinations truly are.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Heritability Estimate | Approximately 40-60% of variance in political attitudes is heritable. |

| Genetic Influence | Genes play a significant role, but environment and socialization also matter. |

| Twin Studies | Identical twins show higher correlation in political beliefs than fraternal twins. |

| Specific Traits | Conservatism, liberalism, and authoritarianism show heritable components. |

| Environmental Factors | Family, education, and cultural exposure significantly shape political views. |

| Longitudinal Studies | Political beliefs stabilize in adulthood, with genetic influence increasing over time. |

| Cross-Cultural Consistency | Heritability of political beliefs is observed across different cultures. |

| Interaction with Environment | Gene-environment interactions (e.g., political climate) influence outcomes. |

| Neurobiological Basis | Brain structures and neurotransmitters (e.g., dopamine) may correlate with political leanings. |

| Evolutionary Perspective | Some political attitudes may have evolutionary roots in survival strategies. |

| Limitations of Studies | Most research is based on Western populations, limiting generalizability. |

| Controversies | Ethical concerns about genetic determinism and potential misuse of findings. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Genetic influences on political ideology

Political beliefs, often seen as products of environment and experience, are increasingly recognized as having a genetic component. Twin studies, which compare identical (monozygotic) and fraternal (dizygotic) twins, have consistently shown that genetic factors account for a significant portion of the variance in political attitudes. For instance, research by John R. Hibbing and colleagues found that heritability estimates for political ideology range between 30% and 60%, depending on the population and methodology. This suggests that genes play a role in shaping whether someone leans conservative or liberal, though they are far from the sole determinant.

To understand how genetics might influence political ideology, consider the role of personality traits like openness to experience and conscientiousness, which are themselves heritable. Individuals high in openness tend to favor liberal policies, while those high in conscientiousness often align with conservative values. Genetic variations in dopamine and serotonin systems, which influence these traits, could thus indirectly shape political preferences. For example, the *DRD4* gene, associated with novelty-seeking behavior, has been linked to more liberal attitudes. While no single "political gene" exists, the cumulative effect of multiple genetic variants can contribute to ideological leanings.

Practical implications of this research extend to political communication and strategy. Understanding the genetic underpinnings of ideology could help tailor messages to resonate with specific audiences. For instance, campaigns might emphasize stability and tradition when addressing genetically predisposed conservatives, while highlighting innovation and change for liberals. However, this approach raises ethical concerns, such as the potential for genetic determinism or discrimination. It is crucial to balance scientific insights with respect for individual agency and environmental influences.

A comparative analysis of heritability across cultures reveals that genetic influences on political ideology are not universal. In homogeneous societies, genetic factors may play a larger role, as environmental cues are more consistent. Conversely, diverse societies with greater ideological variation may show lower heritability, as environmental factors dominate. For example, studies in the U.S. report higher heritability estimates than those in Scandinavia, where political consensus is stronger. This underscores the interplay between genes and environment in shaping beliefs.

In conclusion, while genetic influences on political ideology are undeniable, they are just one piece of a complex puzzle. Genes provide a predisposition, but environment, socialization, and personal experiences ultimately determine an individual’s political stance. Recognizing this interplay allows for a more nuanced understanding of political behavior, moving beyond simplistic nature-versus-nurture debates. As research progresses, integrating genetic insights with sociological and psychological perspectives will be key to unraveling the mysteries of political belief formation.

Reclaim Your Peace: A Guide to Detoxing from Political Overload

You may want to see also

Twin studies and political alignment

Twin studies have long been a cornerstone in unraveling the genetic underpinnings of human traits, and political alignment is no exception. By comparing identical twins, who share 100% of their genes, with fraternal twins, who share approximately 50%, researchers can isolate the influence of genetics from environmental factors. A seminal study published in the *Journal of Politics* found that genetic factors account for about 40-60% of the variance in political attitudes, such as conservatism or liberalism. This suggests that our DNA may predispose us to certain political leanings, though it’s far from the whole story.

Consider the practical implications of these findings. If political beliefs are partly heritable, it could explain why families often share similar ideologies, even when raised in diverse environments. For instance, identical twins raised apart have been found to exhibit striking similarities in their political views, more so than fraternal twins. This doesn’t mean political alignment is set in stone at birth; rather, it highlights the interplay between genetic predispositions and life experiences. Parents or educators seeking to foster open-mindedness might benefit from understanding this dynamic, encouraging dialogue that acknowledges both nature and nurture.

However, interpreting twin studies requires caution. One common critique is the "equal environments assumption," which posits that identical twins share more similar environments than fraternal twins. If this assumption is flawed—say, if identical twins are treated more similarly by parents or peers—it could inflate the estimated genetic influence. Additionally, twin studies often focus on Western populations, limiting their generalizability. Researchers must also disentangle genetic heritability from cultural transmission, where parents pass down beliefs through socialization rather than genes.

Despite these limitations, twin studies offer a compelling lens for understanding political alignment. For example, a 2014 study in *Behavior Genetics* found that heritability of political attitudes increases with age, suggesting that genetic influences may become more pronounced as individuals solidify their beliefs over time. This finding underscores the importance of early exposure to diverse perspectives, as younger individuals may be more malleable in their political development. Policymakers and educators could leverage such insights to design interventions that promote critical thinking and reduce ideological polarization.

In conclusion, twin studies provide valuable, though not definitive, evidence that political alignment has a genetic component. They remind us that while our genes may nudge us toward certain beliefs, they do not dictate them. By integrating these findings with a broader understanding of environmental and social factors, we can foster a more nuanced approach to political discourse—one that acknowledges our shared humanity, even when our beliefs diverge.

Is England's Political System Effective? A Critical Analysis and Debate

You may want to see also

Heritability of conservatism vs. liberalism

Political beliefs, often seen as products of environment and experience, have a surprising genetic component. Twin studies reveal that up to 40-60% of the variance in political attitudes, particularly conservatism versus liberalism, can be attributed to heritability. This doesn’t mean specific beliefs are inherited like eye color, but rather that genetic factors influence traits such as sensitivity to threat, openness to new experiences, and social conformity, which in turn shape political leanings. For instance, individuals with a genetic predisposition toward higher threat sensitivity may gravitate toward conservative policies emphasizing stability and tradition, while those with a genetic inclination toward openness might align with liberal values promoting change and diversity.

Consider the practical implications of this heritability. Parents often assume their political views will directly shape their children’s beliefs, but genetics play a significant role in moderating this influence. A child raised in a conservative household might still lean liberal if their genetic makeup predisposes them to higher openness or lower authoritarianism. Conversely, a child in a liberal household might adopt conservative views if their genetics favor order and structure. This dynamic underscores the importance of understanding genetic predispositions when discussing political socialization, as it explains why siblings raised in the same environment can hold vastly different beliefs.

To explore this further, examine the role of specific genetic traits. Research has identified genetic markers associated with traits like altruism, empathy, and risk tolerance, all of which correlate with political ideologies. For example, a 2014 study found that variations in the DRD4 gene, linked to novelty-seeking behavior, were more common among liberals. Similarly, genes influencing serotonin levels, which affect mood and social behavior, have been tied to conservative tendencies. While these findings are preliminary, they suggest that political beliefs are not solely shaped by upbringing or media consumption but are also rooted in our biological makeup.

However, caution is warranted when interpreting these findings. Heritability does not imply determinism. Environmental factors, such as socioeconomic status, education, and cultural exposure, still play a critical role in shaping political beliefs. Moreover, the interplay between genes and environment is complex; genetic predispositions often manifest differently depending on contextual factors. For instance, a genetically conservative individual might adopt liberal views in a highly progressive society to fit in, illustrating the fluidity of political identities.

In conclusion, the heritability of conservatism versus liberalism highlights the intricate relationship between biology and ideology. While genetic factors contribute significantly to political leanings, they are not the sole determinant. Understanding this interplay can foster greater empathy in political discourse, as it reminds us that differences in belief systems may stem from inherent traits rather than moral failings. By acknowledging the role of genetics, we can move beyond polarization and toward a more nuanced appreciation of political diversity.

Is 'Naya' a Polite Form? Exploring Its Usage and Cultural Significance

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Environmental factors vs. genetic predispositions

The debate over whether political beliefs are heritable often hinges on the interplay between environmental factors and genetic predispositions. Twin studies, a cornerstone of behavioral genetics, suggest that up to 50% of the variance in political attitudes can be attributed to genetic influences. For instance, a 2005 study published in *Psychological Science* found that identical twins, who share 100% of their genes, were more likely to align politically than fraternal twins, who share only 50%. This genetic component doesn’t dictate specific beliefs but rather influences traits like openness to experience or authoritarianism, which correlate with political leanings. However, these findings are not definitive; they highlight a predisposition, not a predetermined outcome.

Environmental factors, on the other hand, play a critical role in shaping political beliefs, often overshadowing genetic predispositions in their immediacy and impact. Family upbringing, socioeconomic status, and cultural norms are potent forces. For example, children raised in households where political discussions are frequent are more likely to adopt similar views, regardless of genetic predisposition. A study by the Pew Research Center found that 70% of adults report holding political beliefs similar to those of their parents, underscoring the power of socialization. Practical steps to mitigate this include exposing oneself to diverse perspectives through media, community engagement, and cross-partisan dialogue, which can counteract the inertia of inherited environments.

The interaction between genes and environment is complex and often bidirectional. For instance, a genetic predisposition toward novelty-seeking might lead an individual to seek out diverse political viewpoints, but only if their environment allows for such exploration. Conversely, a restrictive environment can suppress even the strongest genetic inclinations. Age is a critical factor here: adolescents, whose brains are still developing, are more susceptible to environmental influences, while older adults may lean more heavily on ingrained traits. To navigate this, individuals can consciously curate their environments—joining debate clubs, reading opposing viewpoints, or traveling—to balance genetic predispositions with intentional exposure to new ideas.

A persuasive argument for the dominance of environmental factors lies in the rapid shifts in political beliefs observed across generations. For example, the Baby Boomer generation’s shift from conservative to liberal views over time cannot be explained by genetics alone. External events, such as the Civil Rights Movement or the rise of social media, have reshaped political landscapes more dramatically than any genetic trait could. This suggests that while genetics may load the gun, environment pulls the trigger. To harness this, individuals and societies must prioritize education, media literacy, and inclusive policies that foster critical thinking and adaptability, ensuring that political beliefs are not rigidly bound by either genes or upbringing.

In conclusion, the heritability of political beliefs is a nuanced interplay of genetic predispositions and environmental influences. While genetics may set the stage by influencing personality traits, environment often directs the performance. Practical steps, such as diversifying information sources and engaging in cross-partisan dialogue, can help individuals transcend inherited biases. By understanding this dynamic, we can cultivate more flexible and informed political identities, ensuring that our beliefs are the product of choice, not just chance.

Do Political Donors Still Write Checks? Exploring Modern Campaign Financing

You may want to see also

Cross-cultural genetic variations in politics

Political beliefs, often assumed to be purely products of environment and socialization, exhibit intriguing cross-cultural genetic variations that challenge simplistic explanations. Studies leveraging twin designs and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified heritability estimates for political traits ranging from 30% to 60%, depending on the population and trait measured. However, these estimates are not uniform across cultures. For instance, individualist societies like the United States show higher heritability for traits like social conservatism compared to collectivist societies like Japan, where environmental factors play a more dominant role. This suggests that genetic predispositions interact with cultural norms, shaping political beliefs in context-specific ways.

To explore these variations, consider the role of specific genetic markers. The *DRD4* gene, associated with novelty-seeking behavior, has been linked to political liberalism in Western samples. Yet, in cultures where tradition and conformity are highly valued, this same genetic variant might manifest as a preference for stability rather than change. Similarly, the *MAOA* gene, often dubbed the "warrior gene," influences aggression and has been tied to authoritarianism in some studies. However, its effects differ significantly between cultures with varying norms around conflict resolution and authority. These examples highlight the importance of interpreting genetic associations within their cultural frameworks.

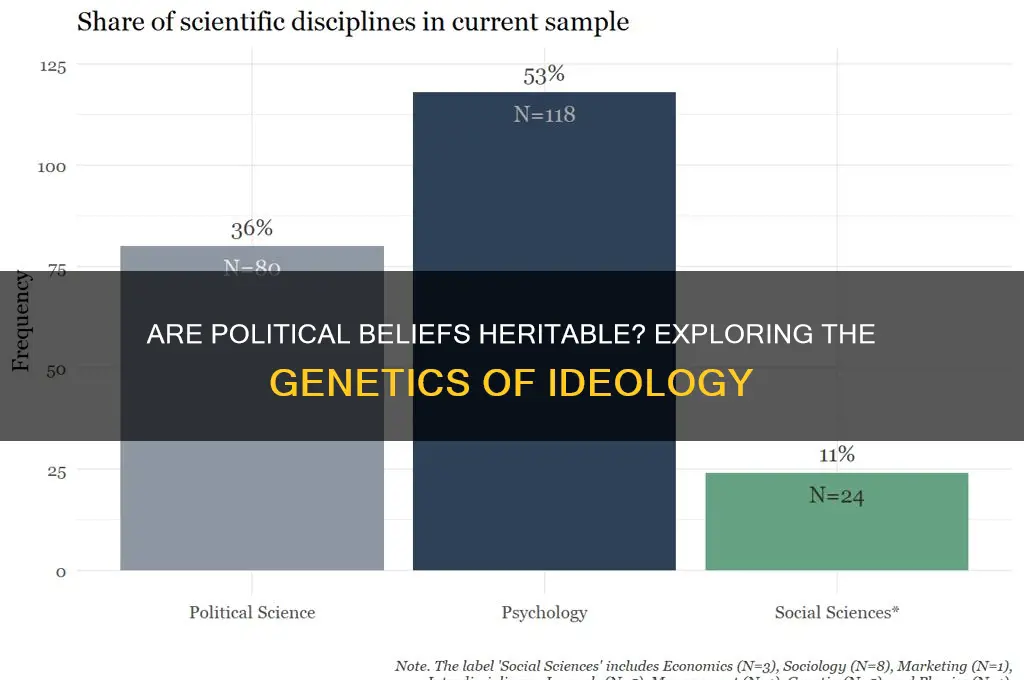

A practical takeaway for researchers is to avoid universalizing findings from Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) societies. For instance, a study on the heritability of political participation in Scandinavia might not replicate in sub-Saharan Africa, where communal decision-making structures differ radically. To address this, cross-cultural collaborations and diverse sample populations are essential. Researchers should also incorporate cultural priming experiments to disentangle genetic effects from learned behaviors. For example, exposing participants to narratives of individualism versus collectivism before assessing political attitudes can reveal how genes and culture interact in real time.

Finally, understanding cross-cultural genetic variations in politics has implications beyond academia. Policymakers and educators can use this knowledge to foster more inclusive political discourse. For instance, recognizing that genetic predispositions toward certain beliefs vary by culture can reduce stigmatization of opposing viewpoints. Similarly, tailoring civic education programs to align with cultural values while encouraging critical thinking can bridge divides. By acknowledging the interplay of genes and culture, we move toward a more nuanced understanding of political diversity—one that respects both biological predispositions and the rich tapestry of human societies.

Navigating Political Turmoil: Strategies to Resolve and Prevent Crises

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Research suggests that political beliefs have a genetic component, with heritability estimates ranging from 30% to 60%, depending on the study. However, this does not mean political beliefs are entirely determined by genetics; environmental and social factors also play significant roles.

Genes may influence traits like personality, cognitive style, and sensitivity to threat or uncertainty, which in turn can shape political preferences. For example, genetic predispositions toward traits like openness or conscientiousness may correlate with specific political ideologies.

No, heritability does not imply immutability. While genetics may predispose individuals to certain beliefs, experiences, education, and social environments can significantly shape or alter political views over time.