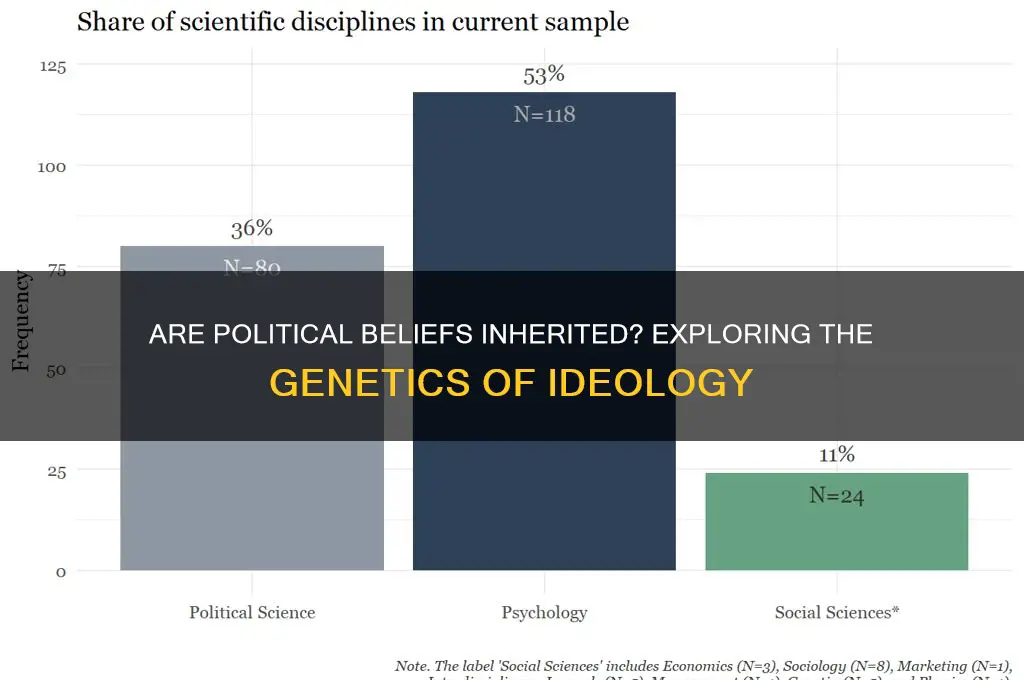

The question of whether political beliefs are heritable has sparked considerable debate across disciplines, blending insights from genetics, psychology, sociology, and political science. While it is clear that environmental factors, such as family upbringing, education, and cultural influences, play a significant role in shaping political ideologies, emerging research in behavioral genetics suggests that genetic predispositions may also contribute to individual differences in political attitudes. Studies on twins and families have indicated that traits like conservatism, liberalism, and even specific policy preferences may have a heritable component, though the exact mechanisms remain poorly understood. This interplay between nature and nurture raises profound questions about the origins of political beliefs and challenges traditional assumptions about their purely social or ideological foundations.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Heritability Estimate | Approximately 30-60% of political attitudes are influenced by genetics. |

| Twin Studies | Studies on twins suggest a genetic component in political ideology. |

| Genetic Influence | Specific genes associated with traits like openness and conscientiousness influence political beliefs. |

| Environmental Factors | Family, culture, education, and socioeconomic status play significant roles. |

| Longitudinal Studies | Political beliefs stabilize in adulthood, with genetics playing a role in consistency. |

| Cross-Cultural Consistency | Heritability of political beliefs is observed across different cultures. |

| Interaction with Environment | Gene-environment interaction (GxE) significantly shapes political attitudes. |

| Neurological Basis | Brain structures and functions linked to personality traits influence political leanings. |

| Temporal Stability | Genetic influences on political beliefs tend to increase with age. |

| Methodological Limitations | Self-report biases and small sample sizes in some studies may affect results. |

| Political Polarization | Genetic predispositions may contribute to ideological polarization. |

| Evolutionary Perspective | Some theories suggest political attitudes evolved as social coordination mechanisms. |

| Epigenetic Factors | Environmental factors can modify gene expression, influencing political beliefs. |

| Reproducibility | Findings on heritability are largely consistent across multiple studies. |

| Policy Implications | Understanding heritability may inform strategies for political engagement and education. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

Genetic Influences on Political Traits

Political beliefs, often seen as products of environment and experience, are increasingly recognized as having a genetic component. Twin studies, a cornerstone of behavioral genetics, reveal that up to 40% of the variance in political attitudes—such as conservatism, liberalism, and authoritarianism—can be attributed to genetic factors. For instance, a 2014 study published in *Behavior Genetics* found that identical twins, who share 100% of their genes, are more likely to align politically than fraternal twins, who share only 50%. This suggests that genetic predispositions play a measurable role in shaping political leanings.

To understand how genes influence political traits, consider the role of personality. Traits like openness to experience and conscientiousness, which are partially heritable, correlate strongly with political ideologies. Liberals, for example, tend to score higher on openness, a trait linked to dopamine receptor genes such as *DRD4*. Conversely, conservatives often exhibit higher conscientiousness, associated with serotonin transporter genes like *5-HTTLPR*. These genetic markers do not dictate beliefs but create a predisposition toward certain attitudes, which are then shaped by environmental factors.

Practical implications of this research extend to political engagement. Studies show that genetic factors influence not only beliefs but also behaviors like voting and activism. For instance, a 2018 analysis in *Nature Genetics* identified specific genetic variants associated with voter turnout. While these variants explain only a small fraction of the variance, they highlight the interplay between biology and civic participation. Parents and educators can use this knowledge to encourage open dialogue, emphasizing that political diversity arises from a combination of nature and nurture.

However, interpreting genetic influences on political traits requires caution. Genetic associations do not imply determinism; they reflect probabilities, not certainties. Environmental factors—such as family, education, and media—remain dominant forces in shaping beliefs. Additionally, the ethical implications of this research are significant. Misinterpretation could lead to genetic essentialism, where individuals are pigeonholed based on their DNA. Instead, this knowledge should foster empathy, underscoring that political differences often stem from innate predispositions rather than moral failings.

In conclusion, genetic influences on political traits offer a nuanced perspective on why people hold divergent beliefs. By acknowledging this biological component, we can move beyond polarized debates and toward a more informed, compassionate understanding of political diversity. While genes provide a foundation, it is the interplay with environment that ultimately shapes our political identities.

Harry Potter's Political Underbelly: Power, Prejudice, and Resistance Explored

You may want to see also

Twin Studies and Ideology Correlations

Twin studies have long been a cornerstone in unraveling the genetic underpinnings of human traits, and political beliefs are no exception. By comparing identical twins, who share 100% of their genes, with fraternal twins, who share approximately 50%, researchers can isolate the influence of genetics versus environment. A landmark study published in the *Journal of Politics* found that genetic factors account for about 40-60% of the variance in political ideology among twins. This suggests that our political leanings are not solely shaped by upbringing or societal influences but are partly hardwired into our DNA.

Consider the practical implications of these findings. If political beliefs have a genetic component, it could explain why siblings raised in the same household often diverge ideologically. For instance, one twin might lean conservative, while the other adopts liberal views, despite sharing the same parents, schools, and socioeconomic environment. This phenomenon challenges the assumption that political socialization is the sole determinant of ideology, highlighting the role of genetic predispositions.

However, interpreting twin studies requires caution. While they reveal correlations, they do not pinpoint specific genes responsible for political beliefs. The heritability estimates are population-specific and can vary across cultures and time periods. For example, a study conducted in Denmark might yield different results than one in the United States due to differences in political systems and societal norms. Additionally, heritability does not imply immutability; genetic predispositions interact with environmental factors, such as education, media exposure, and life experiences, to shape beliefs.

To apply these insights, consider fostering open dialogue across ideological divides. Understanding that political beliefs may have a genetic basis can reduce personal blame and encourage empathy. For parents or educators, this knowledge underscores the importance of exposing young people to diverse perspectives, as genetic predispositions are not destiny. Practical steps include engaging in bipartisan discussions, consuming media from various sources, and encouraging critical thinking about political issues.

In conclusion, twin studies provide compelling evidence that political beliefs are partly heritable, but they are far from deterministic. By acknowledging the interplay between genetics and environment, we can approach ideological differences with greater nuance and tolerance. This perspective not only enriches our understanding of human behavior but also offers a roadmap for bridging political divides in an increasingly polarized world.

Mastering Open Political Conversations: Tips for Respectful and Productive Dialogue

You may want to see also

Environmental vs. Hereditary Factors

The debate over whether political beliefs are shaped more by environmental or hereditary factors is a complex interplay of nature and nurture. Twin studies, a cornerstone of behavioral genetics, suggest that up to 50% of the variance in political attitudes can be attributed to genetic influences. For instance, research on identical twins raised apart has shown striking similarities in their political leanings, such as preferences for conservatism or liberalism. However, these findings do not imply that political beliefs are hardwired; rather, they suggest a predisposition that interacts with environmental factors. This genetic component often manifests as personality traits like openness to experience or conscientiousness, which correlate with specific political ideologies.

Environmental factors, on the other hand, play a pivotal role in shaping how these genetic predispositions are expressed. Family upbringing is a primary influencer, as children often adopt the political beliefs of their parents through socialization. For example, a study found that 70% of adolescents align with their parents’ political party by age 18. Beyond the family, peer groups, education, and media exposure further mold political attitudes. A practical tip for parents or educators is to encourage critical thinking and exposure to diverse viewpoints, which can mitigate the echo chamber effect of homogeneous environments. This approach fosters a more nuanced understanding of politics, even in individuals with strong genetic predispositions.

To illustrate the balance between these factors, consider the case of immigration attitudes. Genetic studies have identified a link between certain genetic markers and a preference for social conformity, which can translate into skepticism toward immigrants. However, environmental factors like local immigration rates, economic conditions, and media narratives significantly modulate this predisposition. For instance, communities with high immigration rates often exhibit more positive attitudes, regardless of genetic tendencies. This example underscores the importance of context in shaping political beliefs, highlighting that heredity provides a baseline, not a destiny.

A comparative analysis of cross-cultural data further complicates the nature vs. nurture dichotomy. In homogeneous societies, genetic influences on political beliefs tend to be more pronounced, as environmental factors are less varied. Conversely, diverse societies show a stronger environmental impact, as individuals are exposed to a wider range of perspectives. For policymakers, this insight suggests that promoting cultural exchange and inclusive education can counteract genetic predispositions that might otherwise lead to polarization. By understanding this interplay, societies can design interventions that encourage tolerance and open dialogue.

Ultimately, the question of whether political beliefs are heritable is not a matter of either-or but of dynamic interaction. While genetics may predispose individuals toward certain attitudes, environmental factors determine how—and whether—these predispositions manifest. A practical takeaway is to approach political discourse with an awareness of this complexity, recognizing that change is possible through intentional environmental interventions. Whether through education, media literacy, or community engagement, fostering diverse environments remains the most effective way to shape political beliefs, regardless of genetic starting points.

Mapping Nations: Understanding the Complex Process of Defining Political Borders

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Cross-Cultural Political Heritability Trends

Political beliefs, often assumed to be shaped solely by personal experiences and societal influences, exhibit intriguing heritability patterns across cultures. Twin studies, a cornerstone of behavioral genetics, reveal that up to 40-60% of the variance in political attitudes can be attributed to genetic factors in Western populations. However, these findings are not universally consistent. In collectivist cultures, such as those in East Asia, the heritability of political beliefs tends to be lower, often ranging between 20-35%. This disparity suggests that cultural values, particularly individualism versus collectivism, play a moderating role in the genetic expression of political ideologies. For instance, in societies where group harmony is prioritized, environmental factors like family and community norms may overshadow genetic predispositions.

To understand these cross-cultural trends, consider the role of socialization processes. In individualistic cultures, where personal autonomy is emphasized, genetic traits like openness to experience or conscientiousness may more directly influence political leanings. Conversely, in collectivist cultures, political beliefs are often inherited through shared family and community values, reducing the direct impact of genetic factors. A practical example is the transmission of conservative values in rural, tightly-knit communities, where conformity to tradition is both culturally and socially enforced, regardless of individual genetic predispositions.

When examining specific political traits, such as authoritarianism or egalitarianism, the heritability rates vary even within cultures. For instance, authoritarian tendencies show higher heritability in cultures with strong hierarchical structures, such as those in parts of the Middle East or South Asia. In contrast, egalitarian beliefs are more heritable in cultures that emphasize equality and fairness, like Scandinavia. This suggests that the content of political beliefs interacts with cultural norms to determine the extent of genetic influence. Researchers recommend analyzing these traits within specific cultural contexts to avoid oversimplification.

A cautionary note is warranted when interpreting these trends. While heritability estimates provide insights into the potential genetic basis of political beliefs, they do not imply determinism. Environmental factors, such as education, media exposure, and socioeconomic status, remain critical in shaping political ideologies. For instance, a genetically predisposed liberal individual raised in a conservative household may still adopt conservative views due to socialization. Practitioners in political science and psychology should integrate both genetic and environmental factors when studying political heritability, particularly in cross-cultural research.

In practical terms, understanding cross-cultural political heritability trends can inform strategies for fostering political dialogue and reducing polarization. For example, in cultures where political beliefs are highly heritable, interventions might focus on creating spaces for intergroup contact to challenge inherited biases. Conversely, in cultures where environmental factors dominate, educational programs emphasizing critical thinking and diverse perspectives could be more effective. By tailoring approaches to cultural contexts, policymakers and educators can promote more nuanced and inclusive political discourse.

Is InterVarsity Shifting Left? Examining Its Political Liberalization

You may want to see also

Epigenetics and Political Behavior Links

Political beliefs, long thought to be shaped solely by environment and personal experience, are now under scrutiny through the lens of epigenetics. This emerging field explores how gene expression is influenced by factors like stress, diet, and social environment, potentially altering traits without changing the underlying DNA sequence. Recent studies suggest that these epigenetic modifications might play a role in shaping political behavior, offering a biological dimension to a traditionally socio-cultural phenomenon.

Consider the impact of early-life stress, a known trigger for epigenetic changes. Research on rodents has shown that maternal stress during pregnancy can lead to offspring with altered stress responses, affecting behaviors related to risk-taking and social interaction. Translating this to humans, it’s plausible that individuals exposed to chronic stress in childhood—whether from poverty, conflict, or family instability—may develop epigenetic markers that predispose them to certain political attitudes. For instance, heightened stress responses could correlate with a preference for authoritarian leadership or conservative policies, as these often promise stability and order.

Epigenetic mechanisms also interact with environmental factors in complex ways. A study published in *Nature Neuroscience* found that exposure to political campaigns during adolescence could leave lasting epigenetic marks, particularly in genes related to dopamine regulation. This suggests that the intensity of political messaging during formative years might "imprint" certain beliefs by altering brain chemistry. For parents and educators, this underscores the importance of fostering critical thinking in young people, as their brains are more susceptible to such influences during this period.

However, the link between epigenetics and political behavior is far from deterministic. Epigenetic changes are reversible, and interventions like mindfulness practices, dietary adjustments, or even targeted therapies could potentially modify these markers. For example, a diet rich in folate and vitamin B12 has been shown to influence DNA methylation, a key epigenetic process. While more research is needed, this opens up possibilities for mitigating the biological roots of political polarization through lifestyle changes.

In practical terms, understanding the epigenetic basis of political beliefs could reshape how we approach civic discourse. Instead of viewing political differences as irreconcilable, we might recognize them as partly rooted in biological responses to environmental cues. This perspective could encourage empathy and reduce ideological rigidity. For policymakers, it highlights the need to address systemic stressors like economic inequality and social injustice, which may have far-reaching epigenetic—and thus political—consequences. The interplay between biology and politics is complex, but it offers a new lens for understanding—and perhaps bridging—our ideological divides.

Brazil's Political Stability: Challenges, Progress, and Future Prospects

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

While there is no direct genetic inheritance of specific political beliefs, research suggests that certain personality traits and cognitive styles, which may influence political leanings, have a genetic component.

Yes, family environment plays a significant role in shaping political beliefs through socialization, exposure to political discussions, and the values and norms modeled by parents and caregivers.

Twin studies have found moderate heritability for traits like conservatism and liberalism, but they also emphasize the strong influence of environmental factors, indicating that both nature and nurture contribute.

Cultural and societal factors often override or shape how genetic predispositions manifest in political beliefs. Genetics may influence how individuals respond to their environment, but the content of political beliefs is largely determined by cultural and societal contexts.