The question of whether political ads constitute propaganda is a contentious and multifaceted issue that lies at the intersection of politics, media, and ethics. While political ads are designed to persuade voters by highlighting a candidate’s strengths or critiquing opponents, they often blur the line between factual information and manipulative messaging. Propaganda, by definition, involves the dissemination of information—often biased or misleading—to influence public opinion and behavior, typically in service of a specific agenda. Critics argue that political ads frequently employ emotional appeals, cherry-picked data, and fear-mongering tactics to sway audiences, aligning them with propagandistic methods. Proponents, however, contend that these ads are a legitimate tool for democratic engagement, allowing candidates to communicate their platforms and differentiate themselves in a competitive political landscape. Ultimately, the distinction hinges on transparency, accuracy, and intent, raising broader questions about the role of media literacy in discerning between persuasive communication and manipulative propaganda.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Definition | Political ads often use persuasive techniques to influence voter opinions, similar to propaganda. |

| Purpose | To promote a candidate, party, or policy while discrediting opponents. |

| Emotional Appeal | Frequently leverages fear, hope, or anger to sway emotions rather than relying on facts. |

| Selective Information | Presents partial truths or omits critical details to shape public perception. |

| Repetition | Repeats key messages or slogans to reinforce ideas in the audience's mind. |

| Demonization of Opponents | Portrays opponents in a negative light, often using misleading or exaggerated claims. |

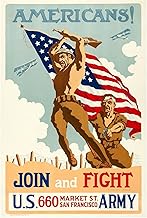

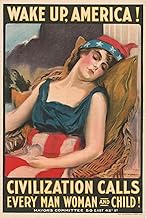

| Use of Symbols and Imagery | Employs flags, colors, or iconic figures to evoke national pride or loyalty. |

| Lack of Transparency | Often funded by undisclosed sources or PACs, making it difficult to verify claims. |

| Targeted Messaging | Uses data-driven strategies to tailor ads to specific demographics or voter groups. |

| Fact-Checking Challenges | Many political ads contain unverified or false claims, complicating fact-checking efforts. |

| Regulation | In many countries, political ads are less regulated than commercial ads, allowing more leeway. |

| Impact on Democracy | Critics argue they undermine informed decision-making by prioritizing emotion over facts. |

Explore related products

What You'll Learn

- Definition of Propaganda: Distinguishing propaganda from informative content in political ads

- Emotional Manipulation: How ads use fear, hope, or anger to sway voters

- Fact vs. Fiction: Analyzing the truthfulness of claims in political advertisements

- Targeted Messaging: Tailoring ads to specific demographics for maximum impact

- Ethical Concerns: Debating the morality of using propaganda in political campaigns

Definition of Propaganda: Distinguishing propaganda from informative content in political ads

Political ads often blur the line between informing and persuading, making it crucial to understand what constitutes propaganda. Propaganda, by definition, is information—especially of a biased or misleading nature—used primarily to influence an audience and further an agenda. In the context of political ads, this can manifest as cherry-picked data, emotional appeals, or outright falsehoods designed to sway voters. Informative content, on the other hand, aims to educate by presenting facts objectively, allowing the audience to form their own conclusions. The challenge lies in identifying when a political ad crosses from informing to manipulating, as the distinction is often subtle but significant.

To distinguish propaganda from informative content, examine the ad’s intent and methods. Propaganda typically relies on emotional triggers—fear, anger, or hope—to bypass critical thinking. For instance, an ad might portray an opponent as a threat to national security without providing evidence, relying instead on ominous imagery and dire warnings. Informative content, however, grounds its claims in verifiable facts, cites sources, and avoids exaggerated language. A key question to ask is: Does the ad encourage independent thought, or does it seek to evoke an immediate, visceral reaction? The latter is a hallmark of propaganda.

Another practical approach is to analyze the ad’s use of language and visuals. Propaganda often employs loaded terms, ad hominem attacks, or oversimplified narratives to frame issues in black-and-white terms. For example, labeling a policy as “dangerous” without explaining why or using dehumanizing imagery to depict opponents are tactics designed to polarize rather than inform. In contrast, informative content uses neutral language, acknowledges complexity, and presents multiple perspectives. Look for balance—if an ad only highlights one side of the story, it’s likely leaning toward propaganda.

Finally, consider the source and transparency of the ad. Propaganda frequently obscures its origins or uses front organizations to appear credible. Political ads funded by undisclosed groups or lacking clear attribution should raise red flags. Informative content, however, is transparent about its sponsors and intentions. Fact-checking organizations and media literacy tools can help verify claims, but the onus is on the viewer to scrutinize the message critically. By understanding these distinctions, audiences can better navigate the flood of political ads and make informed decisions.

Are Fire Departments Political Subdivisions? Exploring Legal and Operational Aspects

You may want to see also

Emotional Manipulation: How ads use fear, hope, or anger to sway voters

Political ads often exploit primal emotions to bypass rational thought, leveraging fear, hope, or anger as tools to manipulate voter behavior. Fear-based ads, for instance, frequently depict dystopian scenarios tied to an opponent’s policies. A classic example is the 1964 "Daisy" ad by Lyndon B. Johnson’s campaign, which linked Barry Goldwater to nuclear war, using a child’s innocence to amplify anxiety. Such ads trigger the brain’s amygdala, hijacking critical thinking and fostering a fight-or-flight response that favors the advertiser’s candidate.

Hope, on the other hand, is wielded to inspire loyalty through aspirational messaging. Barack Obama’s 2008 "Yes We Can" campaign masterfully employed this tactic, using uplifting rhetoric and imagery to rally voters around a vision of change. By tapping into collective aspirations, these ads create an emotional bond, making supporters less likely to question policy specifics. The strategic use of hope transforms candidates into symbols of possibility, often overshadowing their tangible platforms.

Anger is another potent weapon, often directed at external threats or perceived injustices. Donald Trump’s 2016 ads frequently targeted immigrants and "the establishment," framing them as existential dangers to American values. Such messaging activates the brain’s reward system when viewers feel their frustrations validated, fostering a sense of tribalism. This emotional resonance can eclipse factual inaccuracies, as the focus shifts from policy to shared outrage.

To guard against emotional manipulation, voters should adopt a three-step approach: pause, analyze, and verify. When an ad triggers a strong reaction, pause to identify the emotion being exploited. Analyze the ad’s claims objectively, separating rhetoric from evidence. Finally, verify the information through non-partisan sources. Tools like fact-checking websites (e.g., PolitiFact, Snopes) can help dismantle manipulative narratives. By prioritizing critical thinking, voters can reclaim their agency and make informed decisions.

In practice, emotional manipulation in political ads is not inherently evil but inherently strategic. The key lies in recognizing when emotions are being weaponized to circumvent reason. For example, if an ad makes you feel terrified, euphoric, or enraged without offering concrete solutions, it’s likely employing manipulative tactics. Awareness of these techniques empowers voters to engage with political messaging on their own terms, ensuring emotions enhance—rather than replace—rational judgment.

Is 'Bitch' Politically Incorrect? Exploring Language, Context, and Sensitivity

You may want to see also

Fact vs. Fiction: Analyzing the truthfulness of claims in political advertisements

Political advertisements often blur the line between fact and fiction, leveraging emotional appeals and selective information to sway public opinion. To discern truth from manipulation, start by identifying the core claim of the ad. Is it a statement about policy outcomes, an opponent’s record, or a candidate’s achievements? For instance, an ad might claim, “Candidate X created 500,000 jobs in their first term.” Cross-reference this with reliable sources like government reports, nonpartisan fact-checking organizations (e.g., PolitiFact, FactCheck.org), or academic studies. If the number is unverifiable or contradicted by data, the claim is likely exaggerated or false. Always ask: *Where is the evidence?*

Next, scrutinize the context and framing of the information. Political ads frequently use cherry-picked statistics or omit crucial details to paint a misleading picture. For example, an ad might highlight a 10% increase in funding for education without mentioning it was offset by a 20% cut in healthcare. To counter this, compare the ad’s narrative with broader data sets and historical trends. Look for patterns of omission or distortion. A useful rule of thumb: if an ad relies heavily on emotional language or lacks specific details, it’s probably more fiction than fact.

Another critical step is evaluating the source of the ad. Who funded it? Is it a candidate’s official campaign, a political action committee (PAC), or a dark money group? Ads from third-party organizations often have less accountability and are more likely to stretch the truth. For instance, a PAC-funded ad attacking a candidate’s environmental record might use outdated or irrelevant data. Transparency matters—ads that disclose their funding sources are generally more trustworthy. If the source is unclear, treat the claims with skepticism.

Finally, consider the ad’s use of visuals and testimonials. Dramatic imagery, ominous music, or emotional anecdotes can distract from the lack of factual content. For example, an ad might show a struggling family to criticize an opponent’s economic policies, but without data linking those policies to the family’s situation, the connection is speculative. Train yourself to separate style from substance. Ask: *Does this ad rely on facts, or does it manipulate emotions to bypass critical thinking?*

In practice, fact-checking political ads requires vigilance and a commitment to verifying claims independently. Use tools like reverse image searches to confirm the authenticity of visuals, and fact-check specific numbers or quotes in real time. Teach younger audiences, especially those aged 18–24 who are new to voting, to question ads critically rather than accepting them at face value. By systematically analyzing claims, context, sources, and presentation, you can distinguish fact from fiction and make informed decisions in the political arena.

Economics and Politics: Intertwined Forces Shaping Global Policies and Societies

You may want to see also

Explore related products

Targeted Messaging: Tailoring ads to specific demographics for maximum impact

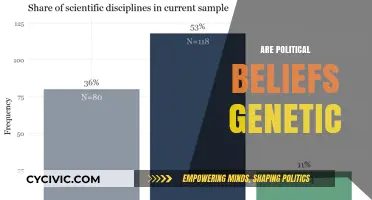

Political ads often blur the line between persuasion and propaganda, especially when they employ targeted messaging. By tailoring ads to specific demographics, campaigns can amplify their impact, but this precision raises ethical questions. For instance, a 2020 study found that 72% of political ads on social media were micro-targeted, using data like age, location, and browsing habits to deliver customized messages. This approach ensures that a 25-year-old urban voter sees a different ad than a 55-year-old rural voter, each designed to resonate with their unique concerns. While effective, this practice can exploit vulnerabilities, turning informed voters into passive recipients of curated narratives.

To craft targeted political ads, campaigns follow a three-step process: segmentation, personalization, and delivery. First, they segment audiences using data analytics, categorizing voters by age, income, race, or political leanings. For example, millennials might be targeted with ads emphasizing student debt relief, while seniors receive messages about Social Security. Next, personalization involves tailoring the message to align with the values or fears of each group. A suburban family might see ads highlighting safety and economic stability, while urban youth could be shown content about climate action. Finally, delivery leverages platforms like Facebook or Instagram, where algorithms ensure ads reach the intended demographic with surgical precision. This method maximizes engagement but risks creating echo chambers that reinforce biases.

Consider the 2016 U.S. presidential election, where targeted messaging played a pivotal role. Cambridge Analytica used psychographic profiling to deliver ads that appealed to specific personality traits, such as authoritarianism or openness. For instance, voters identified as anxious about immigration were bombarded with ads depicting border walls and crime statistics. This strategy, while effective in swaying opinions, sparked debates about manipulation and privacy. Critics argue that such tactics exploit psychological triggers, turning political discourse into a form of propaganda disguised as personalized communication.

To mitigate the risks of targeted messaging, campaigns and platforms must adopt transparency and accountability measures. Voters should be informed when they are being targeted and given the option to opt out of such ads. Platforms like Google and Facebook have introduced ad libraries, allowing users to view all political ads running on their networks. Additionally, regulators could mandate clearer disclosures about data sources and targeting criteria. For instance, an ad might include a tagline like, "This message was tailored based on your age and location." Such practices would balance the efficiency of targeted messaging with ethical considerations, ensuring voters remain informed rather than manipulated.

In conclusion, targeted messaging in political ads is a double-edged sword. When used responsibly, it can engage voters by addressing their specific concerns, fostering a more participatory democracy. However, without safeguards, it risks devolving into propaganda, exploiting divisions and eroding trust in political institutions. Campaigns and platforms must navigate this tension carefully, prioritizing transparency and voter education to ensure that tailored ads serve democracy rather than undermine it.

TV's Role in Regulating Political Ads: Fairness, Transparency, and Accountability

You may want to see also

Ethical Concerns: Debating the morality of using propaganda in political campaigns

Political advertisements often blur the line between persuasion and manipulation, raising profound ethical questions about their use in democratic processes. At their core, these ads aim to influence voter behavior, but the methods employed can veer into propaganda territory, exploiting emotions, fear, or misinformation to sway opinions. This distinction is critical because while persuasion relies on rational arguments and factual evidence, propaganda thrives on distortion and emotional appeals, undermining informed decision-making. The ethical dilemma arises when campaigns prioritize victory over truth, potentially eroding public trust in political institutions.

Consider the 2016 U.S. presidential election, where targeted ads on social media platforms used divisive rhetoric and unverified claims to polarize voters. Such tactics, while effective, exploited vulnerabilities in human psychology, particularly the tendency to accept information that aligns with preexisting beliefs. Ethically, this raises concerns about consent and autonomy: are voters making choices based on genuine understanding, or are they being manipulated into decisions they might not otherwise support? The answer hinges on whether campaigns prioritize transparency and accountability or exploit cognitive biases for political gain.

A comparative analysis of propaganda versus ethical persuasion reveals stark differences. Ethical persuasion involves presenting facts, addressing counterarguments, and allowing audiences to draw conclusions. Propaganda, however, often omits context, cherry-picks data, or uses loaded language to evoke specific reactions. For instance, an ad claiming "Candidate X will destroy our economy" without evidence is propaganda, whereas one detailing specific policy impacts and their potential consequences is persuasive. Campaigns must navigate this divide carefully, ensuring their messaging respects voters' intellectual autonomy.

To address these ethical concerns, practical steps can be taken. First, regulatory bodies could mandate fact-checking for political ads, ensuring claims are verifiable before dissemination. Second, social media platforms should enhance transparency by disclosing ad targeting criteria and funding sources. Third, educational initiatives could empower voters to critically evaluate campaign messages, reducing susceptibility to manipulative tactics. These measures, while not foolproof, would mitigate the moral hazards of propaganda in political campaigns.

Ultimately, the morality of using propaganda in political campaigns hinges on the balance between strategic communication and ethical responsibility. While campaigns have a duty to advocate for their candidates, they also bear a responsibility to uphold democratic values. By prioritizing honesty, transparency, and respect for voters' autonomy, campaigns can navigate this ethical minefield, ensuring their messaging informs rather than manipulates. The challenge lies in reconciling the competitive nature of politics with the principles of fairness and integrity that underpin healthy democracies.

Avoid Political Misinformation: Stay Informed, Not Manipulated

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

Not necessarily. While some political ads may use manipulative tactics similar to propaganda, others provide factual information and fair representations of candidates or policies.

A political ad becomes propaganda when it uses misleading, emotionally charged, or manipulative content to influence public opinion without regard for truth or fairness.

Yes, some political ads mix factual information with manipulative techniques, making them partially informative but still propagandistic in nature.

In most countries, political ads are not explicitly illegal, even if they resemble propaganda. However, regulations vary, and some jurisdictions require transparency or prohibit outright falsehoods.