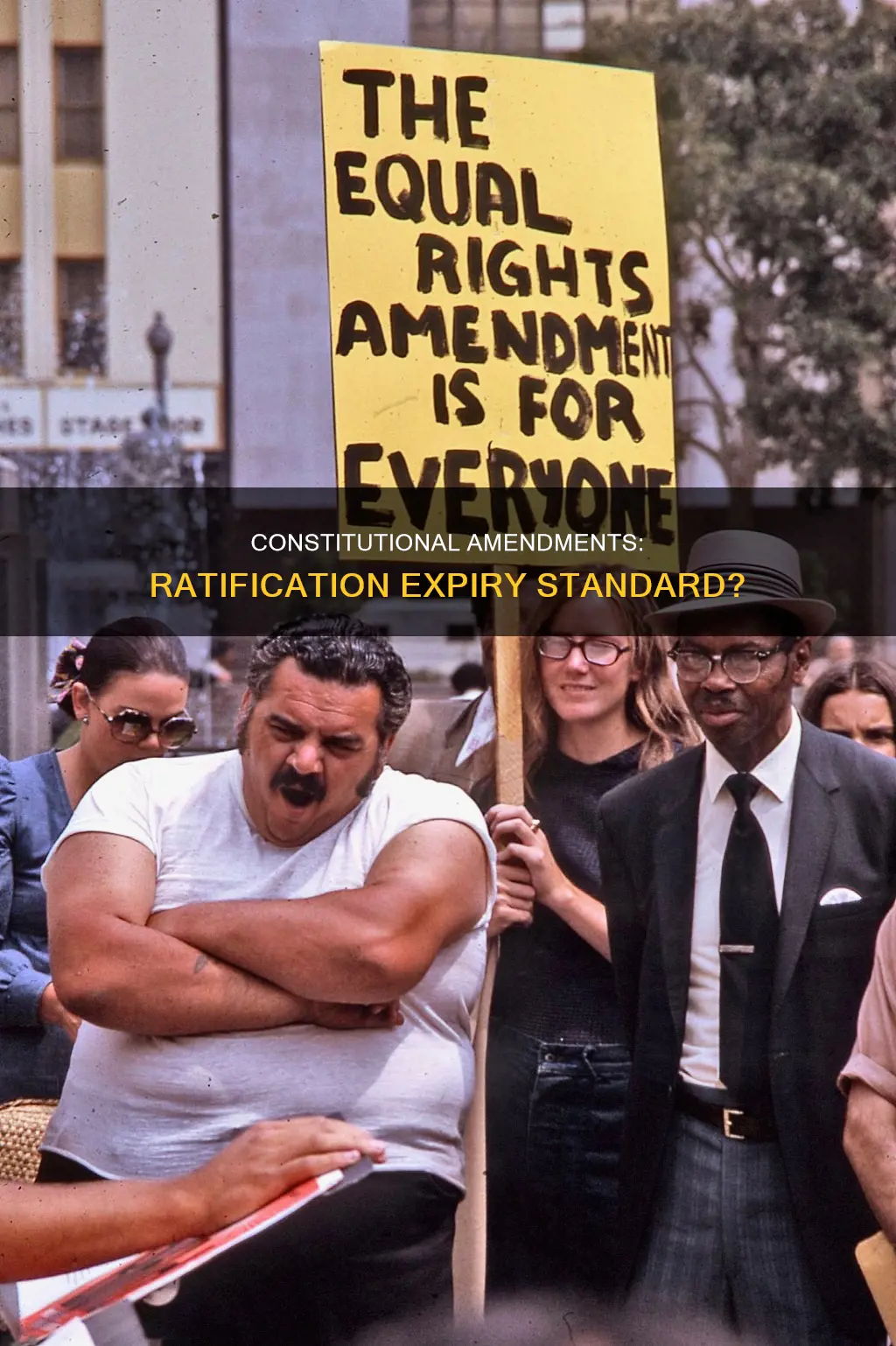

The process of amending the US Constitution is detailed in Article V of the Constitution. Amendments must be proposed and ratified before becoming operative. The US Congress or a national convention can propose an amendment, and it must be ratified by three-fourths of the states to become part of the Constitution. While there is no mention of a time limit for ratification in Article V, Congress has included deadlines in proposed amendments since the 20th Amendment. The question of whether an amendment can be revived after its ratification deadline has expired is a subject of debate, as seen in the case of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), which Illinois voted to ratify 36 years after its ratification deadline.

| Characteristics | Values |

|---|---|

| Who can propose an amendment? | Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, or a national convention called by Congress on the application of two-thirds of state legislatures |

| Who is responsible for administering the ratification process? | The Archivist of the United States, who heads the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) |

| Who is responsible for examining ratification documents? | The Director of the Federal Register |

| Who has the final determination on whether an amendment has expired? | Congress |

| How many states are required to ratify an amendment? | Three-fourths of states (38 out of 50) |

| Is there a time limit for the ratification of a constitutional amendment? | Yes, beginning with the 20th Amendment, Congress has attached a time limit to the ratification of all proposed amendments |

Explore related products

$239.99 $243

What You'll Learn

The role of Congress in the amendment process

The process of amending the US Constitution is outlined in Article V of the Constitution. The process is deliberately difficult and time-consuming, requiring a consensus of support for any amendments. Proposed amendments must be passed by a two-thirds majority in both the House of Representatives and the Senate before being sent to the states for ratification.

Congress plays a critical role in the amendment process, as it is responsible for proposing amendments and determining the mode of ratification. Congress can also extend ratification deadlines and has demonstrated its belief that it may alter a time limit by doing so in the past. In addition, Congress has the power to decide whether or not to accept state ratifications that occur after a deadline.

Once an amendment has been proposed by Congress, it is forwarded to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) for processing and publication. NARA's Office of the Federal Register (OFR) adds legislative history notes and publishes the proposed amendment in slip law format. The OFR also assembles an information package for the states, including formal copies of the joint resolution and the statutory procedure for ratification.

The amendment then goes to the states for ratification, with Congress specifying whether it should be sent to the state legislatures or a state convention. An amendment becomes part of the Constitution when it has been ratified by three-fourths (38) of the states. This process has been used for the ratification of every amendment to the Constitution thus far.

In summary, Congress plays a central role in the amendment process by proposing amendments, determining the mode of ratification, and setting ratification deadlines. It also has the power to adjust or repeal these deadlines and decide whether to accept late state ratifications. The process of amending the Constitution is deliberately challenging, requiring the support of a supermajority in Congress and a majority of states.

The Framers of the US Constitution: A Founding Few

You may want to see also

The role of the Supreme Court in the amendment process

The Supreme Court is the highest court in the United States, and as such, it plays a crucial role in the constitutional amendment process. The Court's primary function in this process is to interpret and ensure compliance with the requirements set out in Article V of the Constitution, which outlines the steps for proposing and ratifying amendments.

The Supreme Court has original jurisdiction over certain cases, such as disputes between states or cases involving ambassadors. It also has appellate jurisdiction over a wide range of cases, including those involving constitutional and federal law. This means that the Court can hear appeals and interpret the Constitution when disputes arise during the amendment process.

One notable example of the Supreme Court's involvement in the amendment process is the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). In 1972, Congress approved the ERA, which aimed to guarantee equal rights regardless of sex. The amendment included a seven-year deadline for ratification by three-fourths of the states. When this deadline was not initially met, Congress extended it to 1982. However, the extension was also unsuccessful, and the ERA was not ratified. The Supreme Court played a role in this process when it dismissed a case regarding the legality of the extended ratification deadline and the ability of states to rescind their ratifications.

In addition to its role in the ERA debate, the Supreme Court has also ruled on other aspects of the amendment process. For instance, in Coleman v. Miller (1939), the Court addressed a ratification dispute, stating that Congress has the final determination regarding the lapse of time and the vitality of a proposed amendment. Furthermore, the Court has interpreted the impact of amendments, such as the Fourteenth Amendment, which expanded the application of the Bill of Rights to the states, and the Due Process Clause, which protects unenumerated rights.

The Supreme Court's role in the amendment process is significant because it ensures that the process adheres to constitutional requirements and interprets the implications of amendments once they are ratified. The Court's decisions can shape the understanding and implementation of amendments, ensuring that the fundamental values and rights enshrined in the Constitution are upheld and applied consistently across the nation.

Executive Agencies: Independence vs Cabinet Control

You may want to see also

The role of the President in the amendment process

The process of amending the US Constitution is outlined in Article V of the Constitution. Notably, the President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process. This means that a joint resolution for an amendment does not go to the White House for signature or approval.

However, in recent history, the President has been involved in the ceremonial function of signing the certification of an amendment. This certification is published in the Federal Register and U.S. Statutes at Large and serves as official notice to the Congress and the Nation that the amendment process has been completed. President Johnson signed the certifications for the 24th and 25th Amendments as a witness, and President Nixon witnessed the certification of the 26th Amendment along with three young scholars.

The process of amending the Constitution begins with a proposal. An amendment may be proposed either by Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate or by a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of the state legislatures. Congress proposes an amendment in the form of a joint resolution.

Once an amendment is proposed, the Archivist of the United States, who heads the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), is responsible for administering the ratification process. The Archivist has delegated many of the ministerial duties associated with this function to the Director of the Federal Register. The Archivist submits the proposed amendment to the States for their consideration by sending a letter of notification to each Governor along with informational material prepared by the OFR.

The mode of ratification is determined by Congress. The amendment must then be ratified by the legislatures of three-fourths (currently 38) of the states. The amendment becomes part of the Constitution once it has been ratified by the required number of states.

In conclusion, while the President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process, they may be involved in ceremonial functions related to the certification of an amendment after it has been ratified by the required number of states. The President's involvement in this ceremonial function demonstrates their recognition of the significance of the amendment process and its completion.

Printing Money: Legal Ways to Make Easy Cash

You may want to see also

Explore related products

The process of ratification by state legislatures

Article V also provides for an alternative process, which has never been utilized. If requested by two-thirds of the state legislatures, Congress shall call a constitutional convention for proposing amendments. Any amendment proposed by that convention must be ratified by three-fourths of the states through a vote of either the state legislature or a state convention. This method is known as the convention method of ratification and is separate and different from a state legislature. It loosely approximates a one-state, one-vote national referendum on a specific proposed federal constitutional amendment, allowing the sentiments of registered voters to be more directly considered.

The mode of ratification is determined by Congress, and in neither of these two processes is a vote by the electorate applicable to the ratification of a constitutional amendment. While Article V does not mention a time limit for the ratification of a constitutional amendment, beginning with the 20th Amendment, Congress has attached a time limit to the ratification of all proposed amendments. For example, the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) had a seven-year time limit, which was later extended by Congress.

The Constitution's Ratification Power: Explaining the Amendment Process

You may want to see also

The process of ratification by state conventions

The convention method of ratification described in Article V is an alternate route to considering the pros and cons of a particular proposed amendment. The framers of the Constitution wanted a means of potentially bypassing the state legislatures in the ratification process. The theory is that the delegates of the conventions, who would presumably be average citizens, might be less likely to bow to political pressure to accept or reject a given amendment than state legislators.

Ratification of a proposed amendment has only been done by state conventions once—the 1933 ratification process of the 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th Amendment. In this case, Congress specified that "conventions in three-fourths of the several States" must ratify the Amendment for it to become operative.

The process of ratification by state convention is more complicated than the state legislature method because it is separate and different from a state legislature. As early as the 1930s, state lawmakers enacted laws to prepare for the possibility of Congress specifying the convention method of ratification. Many laws refer to a one-off event, with an ad-hoc convention convened solely for the purposes of the 21st Amendment. Other laws, however, provided guidelines for ratifying conventions in general. For example, in Vermont, the governor has 60 days to call for the election of delegates to the state ratifying convention. The state convention has 14 members, as many as counties in Vermont. The governor, lieutenant governor, and speaker of the Vermont State House nominate 28 candidates, two from each county: one for ratification and one against.

In the case of the ratification of the Constitution, five state conventions voted to approve the Constitution almost immediately (December 1787 to January 1788) and in all of them, the vote was unanimous (Delaware, New Jersey, Georgia) or lopsided (Pennsylvania, Connecticut).

White House Parties: Where Do They Happen?

You may want to see also

Frequently asked questions

The authority to amend the US Constitution is derived from Article V of the Constitution. Amendments must be proposed and ratified before becoming operative. Amendments can be proposed by Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the Senate and the House of Representatives or by a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of the State legislatures. Once an amendment is proposed, it is sent to the states for ratification by a vote of the state legislatures. An amendment becomes part of the Constitution when it has been ratified by three-fourths (38) of the states.

The Archivist of the United States, who heads the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), is responsible for administering the ratification process. When a state ratifies a proposed amendment, it sends the Archivist an original or certified copy of the state action. The Archivist does not make any substantive determinations as to the validity of state ratification actions but certifies the facial legal sufficiency of ratification documents. Once an amendment is ratified by the required number of states, the Archivist issues a formal proclamation certifying that the amendment is valid and has become part of the Constitution.

There is ambiguity regarding this question. While Congress has included time limits for the ratification of proposed amendments since the 20th Amendment, there is no mention of a time limit for ratification in Article V of the Constitution. In the case of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), Congress extended the ratification deadline, and some argue that Congress has the power to adjust or repeal the time limit constraint on a proposed amendment. However, in National Organization of Women v. Idaho, the Supreme Court dismissed the case as moot because the ERA's deadline had expired, and there is debate over the legality of extending ratification deadlines.

![Ratification of the Twenty-First Amendment of the Constitution of the United States [1938]: State Convention Records and Laws](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/71KMq9r2YgL._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![The Constitution, as Amended, and Ordinances of the Convention of 1866, Together with the Proclamation of the Governor Declaring the Ratification of the Amendments to the 1866 [Leather Bound]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/617DLHXyzlL._AC_UY218_.jpg)

![2nd Amendment No Expiration Gun Permit Die Cut Vinyl Decal Sticker for Car Truck Motorcycle Vehicle Window Bumper Wall Decor Laptop Helmet Size- [12 inch] / [30 cm] Wide || Color- Gloss Black](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61Ij14TK+1L._AC_UY218_.jpg)